Mechanically interlocked molecular architectures

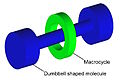

Mechanically interlocked molecular architectures (MIMAs) are molecules that are connected as a consequence of their topology. This connection of molecules is analogous to keys on a key chain loop. The keys are not directly connected to the key chain loop but they cannot be separated without breaking the loop. On the molecular level the interlocked molecules cannot be separated without significant distortion of the covalent bonds that make up the conjoined molecules. Examples of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures include catenanes, rotaxanes, molecular knots, and molecular Borromean rings.[1][2][3]

Work in this area was recognized with the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Bernard ("Ben") L. Feringa, Jean-Pierre Sauvage, and J. Fraser Stoddard .

The synthesis of such entangled architectures has been made efficient through the combination of supramolecular chemistry with traditional covalent synthesis, however mechanically interlocked molecular architectures have properties that differ from both “supramolecular assemblies” and “covalently bonded molecules”. Recently the terminology "mechanical bond" has been coined to describe the connection between the components of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures. Although research into mechanically interlocked molecular architectures is primarily focused on artificial compounds, many examples have been found in biological systems including: cystine knots, cyclotides or lasso-peptides such as microcin J25 which are protein, and a variety of peptides. There is a great deal of interest in mechanically interlocked molecular architectures to develop molecular machines by manipulating the relative position of the components.

Examples of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures

References

- ^ Browne, Wesley R.; Feringa, Ben L."Making molecular machines work" Nature Nanotechnology (2006), vol. 1, pp. 25-35. doi:10.1038/nnano.2006.45

- ^ Stoddart, J. F., "The chemistry of the mechanical bond", Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1802-1820.doi:10.1039/b819333a Coskun, A.; Banaszak, M.; Astumian, R. D.; Stoddart, J. F.; Grzybowski, B. A., "Great expectations: can artificial molecular machines deliver on their promise?", Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, volume 41, pp. 19-30. doi:10.1039/C1CS15262A

- ^ Durola, Fabien; Heitz, Valerie; Reviriego, Felipe; Roche, Cecile; Sauvage, Jean-Pierre; Sour, Angelique; Trolez, Yann "Cyclic [4]Rotaxanes Containing Two Parallel Porphyrinic Plates: Toward Switchable Molecular Receptors and Compressors" Accounts of Chemical Research 2014, volume 47, pp. 633-645. doi:10.1021/ar4002153

Further reading

- G. A. Breault, C. A. Hunter and P. C. Mayers (1999). "Supramolecular topology". Tetrahedron. 55 (17): 5265–5293. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00282-3.