Earth

Earth (often referred to as "the Earth", or "the earth") whose Latin name is Tellus (often incorrectly referred to as Terra, meaning soil) is the third planet in the solar system in terms of distance from the Sun, and the fifth largest. It is also the largest of its planetary system's terrestrial planets, making it the largest solid body in the solar system, and it is the only place in the universe known to support life. The Earth was formed around 4.57 billion years ago[1] and its largest natural satellite, the Moon, was orbiting it shortly thereafter, around 4.533 billion years ago.

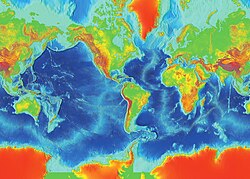

Since it formed, the Earth has changed through geological and biological processes that have hidden traces of the original conditions. The outer surface is divided into several tectonic plates that gradually migrate across the surface over geologic time spans. The interior of the planet remains active, with a thick layer of convecting yet solid Earth mantle and an iron core that generates a magnetic field. The atmospheric conditions have been significantly altered by the presence of life forms, which create an ecological balance that modifies the surface conditions. About 71% of the surface is covered in salt water oceans, and the remainder consists of continents and islands.

There is significant interaction between the Earth and its space environment. The relatively large moon provides ocean tides and has gradually modified the length of the planet's rotation period. A cometary bombardment during the early history of the planet is believed to have played a role in the formation of the oceans. Later, asteroid impacts are understood to have caused significant changes to the surface environment. Changes in the orbit of the planet may also be responsible for the ice ages that have covered significant portions of the surface in glacial sheets.

The Earth's only natural orbiting body is the Moon, although the asteroid Cruithne has been erroneously described as such. Cruithne was discovered in 1986 and follows an elliptical orbit around the Sun at about the same average orbital radius as the Earth. However, from the point of view of the moving Earth, Cruithne follows a horseshoe orbit around the Sun that avoids close proximity with the Earth.

Lexicography

In English usage, the name can be capitalized or spelled in lowercase interchangeably, both when used absolutely or prefixed with "the" (i.e. Earth, the Earth, earth or the earth). Many deliberately spell the name of the planet with a capital, both as "Earth" or "the Earth", so as to distinguish it as a proper noun, distinct from the senses of the term as a count noun or verb (e.g. referring to soil, the ground, earthing in the electrical sense, etc.). Oxford Spelling recognizes the lowercase form as the most common, with the capitalized form as a variant of it. Another convention that is very common is to spell the name with a capital when occurring absolutely (e.g. Earth's atmosphere) and lowercase when preceded by "the" (e.g. the atmosphere of the earth). The term almost exclusively exists in lowercase when appearing in common phrases, even without "the" preceding it (e.g. it doesn't cost the earth; what on earth are you doing?).[2]

Terms that refer to the Earth can use the Latin root terr-, as in terraform and terrestrial. An alternative Latin root is tellur-, which is used in words such as telluric, tellurian, tellurion and tellurium. Both terms derive from terra and tellus respectively, which are Latin words meaning "earth", Terra(soil) and Tallus(the planet).[3] Scientific terms such as geography, geocentric and geothermal use the Greek prefix geo- (γαιο-, gaio-), from gē (again meaning "earth").[4] In many science fictions books and video games, Earth is referred to as Terra or Gaia. Astronauts refer to the Earth as "Terra Firma".

The English word "earth" has cognates in many modern and ancient languages. Examples in modern tongues include aarde in Dutch and Erde in German. The root has cognates in extinct languages such as ertha in Old Saxon and ert (meaning "ground") in Middle Irish, derived from the Old English eorðe. All of these words derive from the Proto-Indo-European base *er-.

Several Semitic languages have words for "earth" similar to those in Indo-European languages. Arabic has aard; Akkadian, irtsitu; Aramaic, araa; Phoenician, erets (which appears in the Mesha Stele); and Hebrew, ארץ (arets, or erets when followed by a noun modifier). The etymological connection between the words in Indo-European and Semitic languages are uncertain, though, and may simply be coincidence.

Words for Earth in other languages include: पृथ्वी pr̥thvī (Sanskrit), maa (Finnish), föld (Hungarian), zemlja (Russian), diqiu (Mandarin), deiqao (Cantonese), jigu (Korean), Bumi (Malay), chikyuu (Japanese), and dunia (Swahili).[5]

Symbol

The astrological symbol for Earth consists of a circled cross, the arms of the cross representing a meridian and the equator. Astronomical symbol has the cross atop the circle (♁).

History

Based on the available evidence, scientists have been able to reconstruct detailed information about the planet's past. Earth is believed to have formed around 4.57 billion years ago out of the solar nebula, along with the Sun and the other planets. Initially molten, the outer layer of the planet cooled when water began accumulating in the atmosphere when the planet was about half its current radius, resulting in the solid crust. The moon formed soon afterwards, possibly as the result of the impact with a Mars-sized object known as Theia (planet). Outgassing and volcanic activity produced the primordial atmosphere; condensing water vapor, augmented by ice delivered by comets, produced the oceans.[6] The highly energetic chemistry is believed to have produced a self-replicating molecule around 4 billion years ago, and half a billion years later, the last common ancestor of all life lived.[7]

The development of photosynthesis allowed the sun's energy to be harvested directly; the resultant oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere and gave rise to the ozone layer. The incorporation of smaller cells within larger ones resulted in the development of complex cells called eukaryotes.[8] Cells within colonies became increasingly specialized, resulting in true multicellular organisms. Aided by the absorption of harmful ultraviolet radiation by the ozone layer, life colonized the surface of Earth.

Over hundreds of millions of years, continents formed and broke up as the surface of Earth continually reshaped itself. The continents have migrated across the surface of the Earth, occasionally combining to form a supercontinent. Roughly 750 million years ago (mya), the earliest known supercontinent Rodinia, began to break apart. The continents later recombined to form Pannotia, 600–540 mya, then finally Pangaea, which broke apart 180 mya.[9]

Since the 1960s, it has been hypothesized that severe glacial action between 750 and 580 mya, during the Neoproterozoic, covered much of the planet in a sheet of ice. This hypothesis has been termed "Snowball Earth", and is of particular interest because it preceded the Cambrian explosion, when multicellular lifeforms began to proliferate.[10]

Since the Cambrian explosion, about 535 mya, there were five mass extinctions.[11] The last occurred 65 mya, when a meteorite collision probably triggered the extinction of the (non-avian) dinosaurs and other large reptiles, but spared small animals such as mammals, which then resembled shrews. Over the past 65 million years, mammalian life has diversified, and several mya, a small African ape gained the ability to stand upright. This enabled tool use and encouraged communication that provided the nutrition and stimulation needed for a larger brain. The development of agriculture, and then civilization, allowed humans to influence the Earth in a short timespan as no other life form had, affecting both the nature and quantity of other life forms, and the global climate.

Shape

The Earth's shape is that of an oblate spheroid, with an average diameter of approximately 12,742 km (~ 40,000 km / π). The rotation of the Earth causes the equator to bulge out slightly so that the equatorial diameter is 43 km larger than the pole to pole diameter. The largest local deviations in the rocky surface of the Earth are Mount Everest (8,850 m above local sea level) and the Mariana Trench (10,924 m below local sea level). Hence compared to a perfect ellipsoid, the Earth has a tolerance of about one part in about 584, or 0.17%. For comparison, this is less than the 0.22% tolerance allowed in billiard balls. Due to the bulge, the feature farthest from the center of the Earth is actually Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador.

Composition

The mass of the Earth is approximately 5980 yottagrams (5.98 ×1024 kg). It is composed mostly of iron (35.1%), oxygen (28.2%), silicon (17.2%), magnesium (15.9%), nickel (1.6%), calcium (1.6%) and aluminium (1.5%) [12].

Internal structure

The interior of the Earth, like that of the other terrestrial planets, is chemically divided into layers. The Earth has an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous mantle, a liquid outer core that is much less viscous than the mantle, and a solid inner core.

The geologic component layers of the Earth[13] are at the following depths below the surface:

| Depth | Layer | |

|---|---|---|

| Kilometres | Miles | |

| 0–60 | 0–37 | Lithosphere (locally varies between 5 and 200 km) |

| 0–35 | 0–22 | ... Crust (locally varies between 5 and 70 km) |

| 35–60 | 22–37 | ... Uppermost part of mantle |

| 35–2890 | 22–1790 | Mantle |

| 100–700 | 62–435 | ... Asthenosphere |

| 2890–5100 | 1790–3160 | Outer core |

| 5100–6378 | 3160–3954 | Inner core |

Tectonic plates

According to plate tectonics theory currently accepted by the vast majority of scientists working in this area, the outermost part of the Earth's interior is made up of two layers: the lithosphere comprising the crust, and the solidified uppermost part of the mantle. Below the lithosphere lies the asthenosphere, which comprises the inner, viscous part of the mantle. The mantle behaves like a superheated and extremely viscous liquid.

The lithosphere essentially floats on the asthenosphere. The lithosphere is broken up into what are called tectonic plates. These plates move in relation to one another at one of three types of plate boundaries: convergent, divergent, and transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along plate boundaries.

The main plates are

- African Plate, covering Africa - Continental plate

- Antarctic Plate, covering Antarctica - Continental plate

- Australian Plate, covering Australia (fused with Indian Plate between 50 and 55 million years ago) - Continental plate

- Eurasian Plate covering Asia and Europe - Continental plate

- North American Plate covering North America and north-east Siberia - Continental plate

- South American Plate covering South America - Continental plate

- Pacific Plate, covering the Pacific Ocean - Oceanic plate

Notable minor plates include the Indian Plate, the Arabian Plate, the Caribbean Plate, the Nazca Plate and the Scotia Plate.

Surface

The Earth's terrain varies greatly from place to place. About 70% of the surface is covered by water, with much of the continental shelf below sea level. If all of the land on Earth were spread evenly, then water would rise to an altitude of more than 2500 metres (approximately 8000 ft.). The remaining 30% not covered by water consists of mountains, deserts, plains, plateaus, etc.

Currently the total arable land is 13.31% of the land surface, with only 4.71% supporting permanent crops.[14] Close to 40% of the Earth's land surface is presently used for cropland and pasture, or an estimated 3.3 × 109 acres of cropland and 8.4 × 109 acres of pastureland.[15]

Extremes

Elevation extremes: (measured relative to sea level)

- Lowest point on land: Dead Sea −417 m

- Lowest point overall: Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean −10,924 m [16]

- Highest point: Mount Everest 8,844 m (2005 est.)

Hydrosphere

The abundance of water on Earth is a unique feature that distinguishes our "Blue Planet" from others in the solar system. Approximately 70.8 percent of the Earth is covered by water and only 29.2 percent is terra firma.

The Earth's hydrosphere consists chiefly of the oceans, but technically includes all water surfaces in the world, including inland seas, lakes, rivers, and underground waters. The average depth of the oceans is 3,794 m (12,447 ft), more than five times the average height of the continents. The mass of the oceans is approximately 1.35 × 10^18 tonnes, or about 1/4400 of the total mass of the Earth.

Atmosphere

The Earth's atmosphere has no definite boundary, slowly becoming thinner and fading into outer space. Three-quarters of the atmosphere's mass is contained within the first 11 km of the planet's surface. This lowest layer is called the troposphere. Further up, the atmosphere is usually divided into the stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere. Beyond these, the exosphere thins out into the magnetosphere (where the Earth's magnetic fields interacts with the solar wind). An important part of the atmosphere for life on Earth is the ozone layer.

The atmospheric pressure on the surface of the Earth averages 101.325 kPa, with a scale height of about 6 km. It is 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, with trace amounts of other gaseous molecules such as water vapor. The atmosphere protects the Earth's life forms by absorbing ultraviolet solar radiation, moderating temperature, transporting water vapor, and providing useful gases. The atmosphere is one of the principal components in determining weather and climate.

Climate

The most prominent features of the Earth's climate are its two large polar regions, two narrow temperate zones, and a wide equatorial tropical region. Precipitation patterns vary widely, ranging from several metres of water per year to less than a millimetre.

Ocean currents are important factors in determining climate, particularly the spectacular thermohaline circulation which distributes heat energy from the equatorial oceans to the polar regions.

Pedosphere

The pedosphere is the outermost layer of the Earth that is composed of soil and subject to soil formation processes. It exists at the interface of the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere.

Biosphere

The planet's lifeforms are sometimes said to form a "biosphere". This biosphere is generally believed to have begun evolving about 3.5 billion (3.5×109) years ago. Earth is the only place in the universe where life is absolutely known to exist, and some scientists believe that biospheres might be rare.

The biosphere is divided into a number of biomes, inhabited by broadly similar flora and fauna. On land, biomes are separated primarily by latitude and height above the sea level. Terrestrial biomes lying within the Arctic, Antarctic Circle or in high altitudes are relatively barren of plant and animal life, while most of the more populous biomes lie near the Equator.

Natural resources

- Earth's crust contains large deposits of fossil fuels: (coal, petroleum, natural gas, methane clathrate). These deposits are used by humans both for energy production and as feedstock for chemical production.

- Mineral ore bodies have been formed in Earth's crust by the action of erosion and plate tectonics. These bodies form concentrated sources for many metals and other useful elements.

- Earth's biosphere produces many useful biological products, including (but far from limited to) food, wood, pharmaceuticals, oxygen, and the recycling of many organic wastes. The land-based ecosystem depends upon topsoil and fresh water, and the oceanic ecosystem depends upon dissolved nutrients washed down from the land.

Some of these resources, such as mineral fuels, are difficult to replenish on a short time scale, called non-renewable resources. The exploitation of non-renewable resources by human civilization has become a subject of significant controversy in modern environmentalism movements.

Land use

- Arable land: 13.13%[14]

- Permanent crops: 4.71%[14]

- Permanent pastures: 26%

- Forests and woodland: 32%

- Urban areas: 1.5%

- Other: 30% (1993 est.)

Irrigated land: 2,481,250 km² (1993 est.)

Natural and environmental hazards

Large areas are subject to extreme weather such as (tropical cyclones), hurricanes, or typhoons that dominate life in those areas. Many places are subject to earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, tornadoes, sinkholes, blizzards, floods, droughts, and other calamities and disasters.

Large areas are subject to human-made pollution of the air and water, acid rain and toxic substances, loss of vegetation (overgrazing, deforestation, desertification), loss of wildlife, species extinction, soil degradation, soil depletion, erosion, and introduction of invasive species.

Long-term climate alteration due to enhancement of the greenhouse effect by human industrial carbon dioxide emissions is an increasing concern, the focus of intense study and debate.

Human geography

Earth has approximately 6,500,000,000 human inhabitants (February 24 2006 estimate).[17] Projections indicate that the world's human population will reach seven billion in 2013 and 9.1 billion in 2050 (2005 UN estimates). Most of the growth is expected to take place in developing nations. Human population density varies widely around the world.

It is estimated that only one eighth of the surface of the Earth is suitable for humans to live on — three-quarters is covered by oceans, and half of the land area is desert, high mountains or other unsuitable terrain.

The northernmost settlement in the world is Alert, Ellesmere Island, Canada. The southernmost is the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, in Antarctica, almost exactly at the South Pole.

There are 267 administrative divisions, including nations, dependent areas, other, and miscellaneous entries. Earth does not have a sovereign government with planet-wide authority. Independent sovereign nations claim all of the land surface except for some segments of Antarctica. There is a worldwide general international organization, the United Nations. The United Nations is primarily an international discussion forum with only limited ability to pass and enforce laws.

In total, about 400 people have been outside the Earth's atmosphere as of 2004, and of these, twelve have walked on the Moon. Most of the time the only humans in space are those on the International Space Station, currently three people. They are replaced every 6 months. See human spaceflight.

Earth in the solar system

It takes the Earth, on average, 23 hours, 56 minutes and 4.091 seconds (one sidereal day) to rotate around the axis that connects the north and the south poles. From Earth, the main apparent motion of celestial bodies in the sky (except that of meteors within the atmosphere and low-orbiting satellites) is to the west at a rate of 15 °/h = 15'/min, i.e., an apparent Sun or Moon diameter every two minutes.

Earth orbits the Sun every 365.2564 mean solar days (1 sidereal year). From Earth, this gives an apparent movement of the Sun with respect to the stars at a rate of about 1 °/day, i.e., a Sun or Moon diameter every 12 hours, eastward. The orbital speed of the Earth averages about 30 km/s (108,000 km/h), which is enough to cover the planet's diameter (~12,600 km) in seven minutes, and the distance to the Moon (384,000 km) in four hours.

The Moon revolves with the Earth around a common barycenter, from fixed star to fixed star, every 27.32 days. When combined with the Earth–Moon system's common revolution around the Sun, the period of the synodic month, from new moon to new moon, is 29.53 days. The Hill sphere (gravitational sphere of influence) of the Earth is about 1.5 Gm (930,000 miles) in radius.

Viewed from Earth's north pole, the motion of Earth, its moon and their axial rotations are all counterclockwise. The orbital and axial planes are not precisely aligned: Earth's axis is tilted some 23.5 degrees against the Earth–Sun plane (which causes the seasons); and the Earth–Moon plane is tilted about 5 degrees against the Earth-Sun plane (without a tilt, there would be an eclipse every two weeks, alternating between lunar eclipses and solar eclipses).

In an inertial reference frame, the Earth's axis undergoes a slow precessional motion with a period of some 25,800 years, as well as a nutation with a main period of 18.6 years. These motions are caused by the differential attraction of Sun and Moon on the Earth's equatorial bulge, due to its oblateness. In a reference frame attached to the solid body of the Earth, its rotation is also slightly irregular due to polar motion. The polar motion is quasi-periodic, containing an annual component and a component with a 14-month period called the Chandler wobble. In addition, the rotational velocity varies, in a phenomenon known as length of day variation.

In modern times, Earth's perihelion occurs around January 3, and the aphelion around July 4 (near the solstices, which are on about December 21 and June 21). For other eras, see precession and Milankovitch cycles.

Magnetic field

The Earth's magnetic field is shaped roughly as a magnetic dipole, with the poles currently located proximate to the planet's geographic poles. The field forms the magnetosphere, which deflects particles in the solar wind. The bow shock is located about at 13.5 RE. The collision between the magnetic field and the solar wind forms the Van Allen radiation belts, a pair of concentric, torus-shaped regions of energetic charged particles. When the plasma enters the Earth's atmosphere at the magnetic poles, it forms the aurora.

The Moon

| Name | Diameter (km) | Mass (kg) | Semi-major axis (km) | Orbital period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moon | 3,474.8 | 7.349×1022 | 384,400 | 27 days, 7 hours, 43.7 minutes |

The Moon, sometimes called 'Luna', is a relatively large, terrestrial, planet-like satellite, with a diameter about one-quarter of the Earth's. It is the largest moon in the solar system relative to the size of its planet. (Charon is larger relative to dwarf planet Pluto.) The natural satellites orbiting other planets are called "moons", after Earth's Moon.

The gravitational attraction between the Earth and Moon cause tides on Earth. The same effect on the Moon has led to its tidal locking: Its rotation period is the same as the time it takes to orbit the Earth. As a result, it always presents the same face to the planet. As the Moon orbits Earth, different parts of its face are illuminated by the Sun, leading to the lunar phases: The dark part of the face is separated from the light part by the solar terminator.

Due to their tidal interaction, the Moon recedes from Earth at the rate of approximately 38 mm a year. Over millions of years, these tiny modifications—and the lengthening of Earth's day by about 17 µs a year—add up to significant changes. During the Devonian period, there were 400 days in a year, with each day lasting 21.8 hours.

The Moon may dramatically affect the development of life by taming the weather. Paleontological evidence and computer simulations show that Earth's axial tilt is stabilized by tidal interactions with the Moon.[18] Some theorists believe that without this stabilization against the torques applied by the Sun and planets to the Earth's equatorial bulge, the rotational axis might be chaotically unstable, as it appears to be for Mars. If Earth's axis of rotation were to approach the plane of the ecliptic, extremely severe weather could result from the resulting extreme seasonal differences. One pole would be pointed directly toward the Sun during summer and directly away during winter. Planetary scientists who have studied the effect claim that this might kill all large animal and higher plant life.[19] However, this is a controversial subject, and further studies of Mars—which shares Earth's rotation period and axial tilt, but not its large moon or liquid core—may settle the matter.

Viewed from Earth, the Moon is just far enough away to have very nearly the same apparent angular size as the Sun (the Sun is 400 times larger, and the Moon is 400 times closer). This allows total eclipses and annular eclipses to occur on Earth.

The most widely accepted theory of the Moon's origin, the giant impact theory, states that it was formed from the collision of a Mars-size protoplanet with the early Earth. This hypothesis explains (among other things) the Moon's relative lack of iron and volatile elements, and the fact that its composition is nearly identical to that of the Earth's crust.

Earth has at least two co-orbital satellites, the asteroids 3753 Cruithne and 2002 AA29.

Descriptions of Earth

Earth has often been personified as a deity, in particular a goddess (see Gaia and Mother Earth). The Chinese Earth goddess Hou-Tu is similar to Gaia, the deification of the Earth. As the patroness of fertility, her element is Earth. In Norse mythology, the Earth goddess Jord was the mother of Thor and the daughter of Annar. Ancient Egyptian mythology is different from that of other cultures because Earth is male, Geb, and sky is female, Nut (goddess).

Although commonly thought to be a sphere, the Earth is actually an oblate spheroid. It bulges slightly at the equator and is slightly flattened at the poles. In the past there were varying levels of belief in a flat Earth, but ancient Greek philosophers and, in the Middle Ages, thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas believed that it was spherical.

A 19th-century organization called the Flat Earth Society advocated the even-then discredited idea that the Earth was actually disc-shaped, with the North Pole at its center and a 150 foot (50 m) high wall of ice at the outer edge. It and similar organizations continued to promote this idea, based on religious beliefs and conspiracy theories, through the 1970s. Today, the subject is more frequently treated tongue-in-cheek or with mockery.

Prior to the introduction of space flight, these inaccurate beliefs were countered with deductions based on observations of the secondary effects of the Earth's shape and parallels drawn with the shape of other planets. Cartography, the study and practice of map making, and vicariously geography, have historically been the disciplines devoted to depicting the Earth. Surveying, the determination of locations and distances, and to a somewhat lesser extent navigation, the determination of position and direction, have developed alongside cartography and geography, providing and suitably quantifying the requisite information.

The technological developments of the latter half of the 20th century are widely considered to have altered the public's perception of the Earth. Before space flight, the popular image of Earth was of a green world. Science fiction artist Frank R. Paul provided perhaps the first image of a cloudless blue planet (with sharply defined land masses) on the back cover of the July 1940 issue of Amazing Stories, a common depiction for several decades thereafter. [20] Apollo 17's 1972 "Blue Marble" photograph of Earth from cislunar space became the current iconic image of the planet as a marble of cloud-swirled blue ocean broken by green-brown continents. A photo taken of a distant Earth by Voyager 1 in 1990 inspired Carl Sagan to describe the planet as a "Pale Blue Dot." [21] Earth has also been described as a massive spaceship, with a life support system that requires maintenance, or as having a biosphere that forms one large organism. See Spaceship Earth and Gaia theory.

Earth's future

The future of the planet is closely tied to that of the Sun. The luminosity of the Sun will continue to steadily increase, growing from the current luminosity by 10% in 1.1 billion years (1.1 Gyr) and up to 40% in 3.5 Gyr.[22] Climate models indicate that the increase in radiation reaching the Earth is likely to have dire consequences, including possible loss of the oceans.[23]

The Sun, as part of its solar lifespan, will expand to a red giant in 5 Gyr. Models predict that the Sun will expand out to about 99% of the distance to the Earth's present orbit (1 astronomical unit, or AU). However by that time the orbit of the Earth will expand to about 1.7 AUs due to mass loss by the Sun. The planet will thus escape envelopment.[22]

See also

| Subtopic | Links |

|---|---|

| Astronomy | Darwin (ESA) · Terrestrial Planet Finder |

| Ecology | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment |

| Economy | World economy |

| Fiction | Hollow Earth · Journey to the Center of the Earth · Earth in fiction · The Core |

| Geography, Geology |

Continents · Timezones · Degree Confluence Project · Earthquake · Extremes on Earth · Plate tectonics · Equatorial bulge |

| History | Geologic time scale · Human history · Origin and evolution of the solar system · Timeline of evolution |

| Law | International law |

| Mapping | Google Earth · World Wind |

| Politics | List of countries |

References

- NASA's Earth fact sheet

- Discovering the Essential Universe (Second Edition) by Neil F. Comins (2001)

- space.about.com - Earth - Pictures and Astronomy Facts

Notes

- ^ G.B. Dalrymple, 1991, "The Age of the Earth", Stanford University Press, California, ISBN 0-8047-1569-6.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Dictionary.com

- ^ Dictionary.com

- ^ http://www.seds.org/nineplanets/nineplanets/days.html

- ^ A. Morbidelli et al, 2000, "Source Regions and Time Scales for the Delivery of Water to Earth", Meteoritics & Planetary Science, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 1309–20.

- ^ W. Ford Doolitte, "Uprooting the Tree of Life", Scientific American, Feb. 2000.

- ^ L. V. Berkner, L. C. Marshall, 1965, "On the Origin and Rise of Oxygen Concentration in the Earth's Atmosphere", Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 225–61.

- ^ J.B. Murphy, R.D. Nance, "How do supercontinents assemble?", American Scientist, vol. 92, pp. 324–33.

- ^ J.L. Kirschvink, 1992, "Late Proterozoic Low-Latitude Global Glaciation: The Snowball Earth", The Proterozoic Biosphere, pp 51–52.

- ^ D. Raup & J. Sepkoski, 1982, "Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record", Science, vol. 215, pp. 1501–03.

- ^ http://earthref.org/cgi-bin/er.cgi?s=erda.cgi?n=547

- ^ T. H. Jordan, "Structural Geology of the Earth's Interior", Proceedings National Academy of Science, 1979, Sept., 76(9): 4192–4200.

- ^ a b c CIA: The World Factbook, "World".

- ^ FAO, 1995, "United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization Production Yearbook", 49.

- ^ ""Deep Ocean Studies"". Ocean Studies. RAIN National Public Internet and Community Technology Center. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^

David, Leonard (2006-02-24). "Planet's Population Hit 6.5 Billion Saturday". Live Science. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A.C.M., Levrard, B., 2004, "A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 428, pp. 261–85.

- ^ Williams, D.M., J.F. Kasting, 1997, "Habitable planets with high obliquities", Icarus 129, 254–68.

- ^ Ackerman, Forrest J (1997). Forrest J Ackerman's World of Science Fiction. Los Angeles: RR Donnelley & Sons Company. pp. 116–117. ISBN 1-57544-069-5.

- ^ "Pale Blue Dot". SETI@home. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ^ a b I.J. Sackmann, A.I. Boothroyd, K.E. Kraemer, "Our Sun. III. Present and Future.", Astrophysical Journal, vol. 418, pp. 457.

- ^ J.F. Kasting, 1988, "Runaway and Moist Greenhouse Atmospheres and the Evolution of Earth and Venus", Icarus, 74, pp. 472-494.

External links

- WikiSatellite view of Earth at WikiMapia

- USGS Geomagnetism Program

- Overview of the Seismic Structure of Earth Template:PDFlink

- NASA Earth Observatory

- Beautiful Views of Planet Earth Pictures of Earth from space

- Java 3D Earth's Globe

- Projectshum.org's Earth fact file (for younger folk)

- Geody Earth World's search engine that supports Google Earth, NASA World Wind, Celestia, GPS, and other applications.