Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture (Arabic عمارة إسلامية, Turkish İslami mimari) describes the entire range of architecture that has evolved within Muslim culture in the course of the history of Islam. Hence the term encompasses religious buildings as well as secular ones, historic as well as modern expressions and the production of all places that have come under the varying levels of Islamic influence and hence became a part of Islamic studies.

It is very common to mistake Persian Architecture for Islamic Architecture and thus it is advisable to read both articles.

Classification of Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture can be classified according to

- Chronology

- Geography

- Building Typology

Elements of Islamic style

Islamic architecture may be identified with the following design elements, which were inherited from the first mosque built by Muhammad in Medina, as well as from other pre-Islamic features adapted from churches and synagogues. Byzantine architecture had a great influence on early Islamic architecture with its characteristic round arches, vaults and domes.

- Large courtyards often merged with a central prayer hall (originally a feature of the Masjid al-Nabawi).

- Minarets or towers (these were originally used as torch-lit watchtowers, as seen in the Great Mosque of Damascus; hence the derivation of the word from the Arabic nur, meaning "light").

- Mihrab or niche on an inside wall indicating the direction to Mecca. This may have been derived from previous uses of niches for the setting of the torah scrolls in Jewish synagogues or the haikal of Coptic churches.

- Iwans to intermediate between different sections.

- The use of decorative Islamic calligraphy instead of pictures which were haram (forbidden) in mosque architecture. Note that in secular architecture, pictures were indeed present.

- The use of bright color.

- Focus both on the interior space of a building and the exterior.

Interpretation

Common interpretations of Islamic architecture include the following: The concept of Allah's infinite power is evoked by designs with repeating themes which suggest infinity. Human and animal forms are rarely depicted in decorative art as Allah's work is considered to be matchless. Foliage is a frequent motif but typically stylized or simplified for the same reason. Arabic Calligraphy is used to enhance the interior of a building by providing quotations from the Qur'an. Islamic architecture has been called the "architecture of the veil" because the beauty lies in the inner spaces (courtyards and rooms) which are not visible from the outside (street view). Furthermore, the use of grandiose forms such as large domes, towering minarets, and large courtyards are intended to convey power.

Influences

A specifically Islamic architectural style developed soon after the Prophet Muhammad. From the beginning the style grew from Roman, Egyptian, Persian/Sassanid, and Byzantine styles. An early example may be identified as early as AD 691 with the completion of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhrah) in Jerusalem. It featured interior vaulted spaces, a circular dome, and the use of stylized repeating decorative patterns (arabesque).

The Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq, completed in AD 847, combined the hypostyle architecture of rows of columns supporting a flat base above which a huge spiraling minaret was constructed.

The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul also influenced Islamic architecture. When the Ottomans captured the city from the Byzantines, they converted the basilica to a mosque (now a museum) and incorporated Byzantine architectural elements into their own work (e.g. domes). The Hagia Sophia also served as model for many of the Ottoman mosques such as the Shehzade Mosque, the Suleiman Mosque, and the Rüstem Pasha Mosque.

Persian architecture

One of the first civilizations that Islam came into contact with during and after its birth was that of Persia. The eastern banks of the Tigris and Euphrates was where the capital of the Persian empire lay during the 7th century. Hence the proximity often led early Islamic architects to not just borrow, but adopt the traditions and ways of the fallen Persian empire.

Islamic architecture borrows heavily from Persian architecture and in many ways can be called an extension and further evolution of Persian architecture.

Many cities such as Baghdad, for example, were based on precedents such as Firouzabad in Persia. In fact, it is now known that the two designers who were hired by al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian, and Mashallah, a former Jew from Khorasan, Iran.

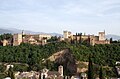

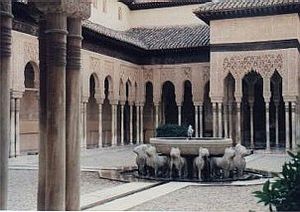

Moorish architecture

Construction of the Great Mosque at Cordoba beginning in 785 AD marks the beginning of Islamic architecture in Spain and Northern Africa (see Moors). The mosque is noted for its striking interior arches. Moorish architecture reached its peak with the construction of the Alhambra, the magnificent palace/fortress of Granada, with its open and breezy interior spaces adorned in red, blue, and gold. The walls are decorated with stylize foliage motifs, Arabic inscriptions, and arabesque design work, with walls covered in glazed tile.

Even after the completion of the Reconquista, Islamic influence had a lasting impact on the architecture of Spain. In particular, medieval Spaniards used the Mudéjar style, an imitation of Islamic design. One of the best examples of the Moors' lasting impact is the Alcázar of Seville.

Timurid architecture

Timurid architecture is the pinnacle of Islamic art in Central Asia. Spectacular and stately edifices erected by Timur and his successors in Samarkand and Herat helped to disseminate the influence of the Ilkhanid school of art in India, thus giving rise to the celebrated Moghol school of architecture. Timurid architecture started with the sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi in present-day Kazakhstan and culminated in Tumir's mausoleum Gur-e Amir in Samarkand. The style is largely derived from Persian architecture. Axial symmetry is a characteristic of all major Timurid structures, notably the Shah-e Zendah in Samarkand and the mosque of Gowhar Shad in Meshed. Double domes of various shapes abound, and the outsides are perfused with brilliantly colored

Ottoman/Turkish architecture

The architecture of the Turkish Ottoman Empire forms a distinctive whole, especially the great mosques by and in the style of Sinan, like the mid-16th century Suleiman Mosque. For almost 500 years Byzantine architecture such as the church of Hagia Sophia served as models for many of the Ottoman mosques such as the Shehzade Mosque, the Suleiman Mosque, and the Rüstem Pasha Mosque.

The Ottomans achieved the highest level architecture in the Islamic lands hence or since. They mastered the technique of building vast inner spaces confined by seemingly weightless yet massive domes, and achieving perfect harmony between inner and outer spaces, as well as light and shadow. Islamic religious architecture which until then consisted of simple buildings with extensive decorations, was transformed by the Ottomans through a dynamic architectural vocabulary of vaults, domes, semidomes and columns. The mosque was transformed from being a cramped and dark chamber with arabesque-covered walls into a sanctuary of esthetic and technical balance, refined elegance and a hint of heavenly transcendence.

Fatemid architecture

In architecture, the Fatimids followed Tulunid techniques and used similar materials, but also developed those of their own. In Cairo, their first congregational mosque was al-Azhar mosque ("the splendid") founded along with the city (969–973), which, together with its adjacent institution of higher learning (al-Azhar University), became the spiritual center for Ismaili Shia. The Mosque of al-Hakim (r. 996–1013), an important example of Fatimid architecture and architectural decoration, played a critical role in Fatimid ceremonial and procession, which emphasized the religious and political role of the Fatimid caliph. Besides elaborate funerary monuments, other surviving Fatimid structures include the Mosque of al-Aqmar (1125) as well as the monumental gates for Cairo's city walls commissioned by the powerful Fatimid emir and vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1073–1094).

Al-Hakim Mosque 990AD-1012AD, renovated by Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin (Head of Dawoodi Bohra community) and Al-Jame-al-Aqmar built in 519H/1125AD in Cairo, Egypt features with its Fatemi philosophy and symbolism and bring its architecture vividly to life.

Mughal architecture

Another distinctive sub-style is the architecture of the Mughal Empire in India in the 16th century and a fusion of Persian and Hindu elements. The Mughal emperor Akbar constructed the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri, located 26 miles west of Agra, in the late 1500s.

The most famous example of Mughal architecture is the Taj Mahal, the "teardrop on eternity," completed in 1648 by the emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal who died while giving birth to their 14th child. The extensive use of precious and semiprecious stones as inlay and the vast quantity of white marble required nearly bankrupted the empire. The Taj Mahal is completely symmetric other than the sarcophagus of Shah Jahan which is placed off center in the crypt room below the main floor. This symmetry extended to the building of an entire mirror mosque in red sandstone to complement the Mecca-facing mosque place to the west of the main structure. Another structure built that showed great depth of mughal influence was the Shalimar Gardens.

Sino-Islamic architecture

The first Chinese mosque was established in the 8th century during the Tang Dynasty in Xi'an. The Great Mosque of Xi'an, whose current buildings date from the Ming Dynasty, does not replicate many of the features often associated with traditional mosques. Instead, it follows traditional Chinese architecture. Mosques in western China incorporate more of the elements seen in mosques in other parts of the world. Western Chinese mosques were more likely to incorporate minarets and domes while eastern Chinese mosques were more likely to look like pagodas.[1]

An important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur; this applies to everything from palaces to mosques. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow; to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself.

Chinese buildings may be built with either red or grey bricks, but wooden structures are the most common; these are more capable of withstanding earthquakes, but are vulnerable to fire. The roof of a typical Chinese building is curved; there are strict classifications of gable types, comparable with the classical orders of European columns.

Afro-Islamic architecture

The Islamic conquest of North Africa saw Islamic architecture develop in the region, including such famous structures as the Cairo Citadel.

South of the Sahara, Islamic influence was a major contributing factor to architectural development from the time of the Kingdom of Ghana. At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in domed huts, but traders had stone houses. Sahelian architecture initially grew from the two cities of Djenné and Timbuktu. The Sanskore Mosque in Timbuktu, constructed from mud on timber, was similar in style to the Great Mosque of Djenné. The rise of kingdoms in the West African coastal region produced architecture which drew instead on indigenous traditions, utilising wood. The famed Benin City, destroyed by the Punitive Expedition, was a large complex of homes in coursed mud, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves. The Palace had a sequence of ceremonial rooms, and was decorated with brass plaques.

Architecture of mosques and buildings in Muslim countries

Styles

Many forms of Islamic architecture have evolved in different regions of the Islamic world. Notable Islamic architectural types include the early Abbasid buildings, T-type mosques, and the central-dome mosques of Anatolia. The oil-wealth of the 20th century drove a great deal of mosque construction using designs from leading non-Muslim modern architects and promoting the careers of important contemporary Muslim architects.

Arab-plan or hypostyle mosques are the earliest type of mosques, pioneered under the Umayyad Dynasty. These mosques are square or rectangular in plan with an enclosed courtyard and a covered prayer hall. Historically, because of the warm Mediterranean and Middle Eastern climates, the courtyard served to accommodate the large number of worshipers during Friday prayers. Most early hypostyle mosques have flat roofs on top of prayer halls, necessitating the use of numerous columns and supports.[2] One of the most notable hypostyle mosques is the Mezquita in Córdoba, Spain, as the building is supported by over 850 columns.[3] Frequently, hypostyle mosques have outer arcades so that visitors can enjoy some shade. Arab-plan mosques were constructed mostly under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties; subsequently, however, the simplicity of the Arab plan limited the opportunities for further development, and as a result, these mosques gradually fell out of popularity.[2]

The Ottomans introduced central dome mosques in the 15th century and have a large dome centered over the prayer hall. In addition to having one large dome at the center, there are often times smaller domes that exist off-center over the prayer hall or throughout the rest of the mosque, where prayer is not performed.[4] This style was heavily influenced by the Byzantine religious architecture with its use of large central domes.[2]

Iwan

An iwan is defined as a vaulted hall or space, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open.

Iwans were a trademark of the Sassanid architecture of Persia, later finding their way into Islamic architecture. This transition reached its peak during the Seljuki era when iwans became established as a fundamental design unit in Islamic architecture. Typically, iwans open on to a central courtyard, and have been used in both public and residential architecture.

Iwan mosques are most notable for their domed chambers and iwans, which are vaulted spaces open out on one end. In iwan mosques, one or more iwans face a central courtyard that serves as the prayer hall. The style represents a borrowing from pre-Islamic Iranian architecture and has been used almost exclusively for mosques in Iran. Many iwan mosques are converted Zoroastrian fire temples where the courtyard was used to house the sacred fire.[2] Today, iwan mosques are no longer built.[4]

Sahn

Almost every mosque and many houses and buildings in areas of the Muslim World contain a religious courtyard known as a sahn (Arabic صحن), which are surrounded on all sides by an arcade. Sahns usually feature a centrally positioned, symmetrical axis pool known as a howz, where ablutions are performed. Some sahns also contain drinking fountains.

If a sahn is in a mosque, it is used for performing ablutions. If a sahn is in a traditional house or private courtyard, it is used for bathing, for aesthetics, or for both.

Arabesque

An element of Islamic art usually found decorating the walls of mosques and Muslim homes and buildings, the arabesque is an elaborate application of repeating geometric forms that often echo the forms of plants, shapes and sometimes animals (specifically birds). The choice of which geometric forms are to be used and how they are to be formatted is based upon the Islamic view of the world. To Muslims, these forms, taken together, constitute an infinite pattern that extends beyond the visible material world. To many in the Islamic world, they in fact symbolize the infinite, and therefore uncentralized, nature of the creation of the one God (Allah). Furthermore, the Islamic Arabesque artist conveys a definite spirituality without the iconography of Christian art. Arabesque is used in mosques and building around the Muslim world, and it is a way of decorating using beautiful, embellishing and repetitive Islamic art instead of using pictures of humans and animals (which is forbidden Haram in Islam).

Islamic Calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art (the Arabesque) on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on the page. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions in their work.

Instead of recalling something related to the reality of the spoken word, calligraphy for the Muslim is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the spiritual world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, al-Qur'an, has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and complete passages from the Qur'an are still active sources for Islamic calligraphy.

Gallery

See also

- Islamic Golden Age

- Architecture

- Mosque

- Madrassa

- Aga Khan Award for Architecture

- Hispano-Moresque Pottery

- Sahn

Bibliography

The Art and Architecture of Islam: 650 - 1250, by Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Grabar, Penguin USA, 1987. Indo-Iranian Socio-Cultural Relations at Past, Present and Futur, by M.Reza Pourjafar, Ali A. Taghvaee, in - Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony (Fabio Maniscalco ed.), vol. 1, January-June 2006

External links

- Fons Vitae - Islamic Architecture of Cairo

- Islamic Art Network - Thesaurus Islamicus Foundation

- http://www.osmanlimedeniyeti.com Many articles about the Ottoman Turkish Mosques and Mosque architecture (in Turkish)

- Discussion of Islamic architecture

- http://www.3dkabah.com A 3D model of the Grand Mosque in Makkah, with pictures and videos

- Photographs from Lahore's Mughal period walled city

- Great Mosque of Sammarra

- Watch "Isfahan the Movie" on QuickTime Player to see superb example of Islamic architecture.

- Islamic Architecture org.

- Gallery of Islamic Architecture

- Article, "What is Islamic Architecture?"

- Article, "The Mosque of Two Pillars at Georgetown University"

- ^ Cowen, Jill S. (July/August 1985). "Muslims in China: The Mosque". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 30–35. Retrieved 2006-04-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Masdjid1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Religious Architecture and Islamic Cultures". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-04-09.

- ^ a b "Vocabulary of Islamic Architecture". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-04-09.