Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford | |

|---|---|

| |

| 38th President of the United States | |

| In office August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977 | |

| Vice President | Nelson Rockefeller |

| Preceded by | Richard Nixon |

| Succeeded by | Jimmy Carter |

| 40th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office December 6, 1973 – August 9, 1974 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Spiro Agnew |

| Succeeded by | Nelson Rockefeller |

| House Minority Leader | |

| In office January 3, 1965 – December 6, 1973 | |

| Deputy | Leslie C. Arends |

| Preceded by | Charles A. Halleck |

| Succeeded by | John Jacob Rhodes |

| Chair of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office January 3, 1963 – January 3, 1965 | |

| Leader | Charles A. Halleck |

| Preceded by | Charles B. Hoeven |

| Succeeded by | Melvin Laird |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Michigan's 5th district | |

| In office January 3, 1949 – December 6, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Bartel J. Jonkman |

| Succeeded by | Richard Vander Veen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Leslie Lynch King, Jr. July 14, 1913 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | December 26, 2006 (aged 93) Rancho Mirage, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | Michael Jack Steven Susan |

| Education | University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (BA) Yale University (LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | American Campaign Medal Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (9 campaign stars) World War II Victory Medal |

Gerald Rudolph Ford, Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King, Jr.; July 14, 1913 – December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th President of the United States from 1974 to 1977, following the resignation of Richard Nixon. Prior to this he served eight months as the 40th Vice President of the United States, following the resignation of Spiro Agnew. He was the first person appointed to the vice presidency under the terms of the 25th Amendment, and consequently the only person to have served as both Vice President and President of the United States without being elected to executive office. Before his appointment to the vice presidency, Ford served 25 years as U.S. Representative from Michigan's 5th congressional district, the final nine of them as the House Minority Leader.

As President, Ford signed the Helsinki Accords, marking a move toward détente in the Cold War. With the conquest of South Vietnam by North Vietnam nine months into his presidency, U.S. involvement in Vietnam essentially ended. Domestically, Ford presided over the worst economy in the four decades since the Great Depression, with growing inflation and a recession during his tenure.[1] One of his most controversial acts was to grant a presidential pardon to President Richard Nixon for his role in the Watergate scandal. During Ford's presidency, foreign policy was characterized in procedural terms by the increased role Congress began to play, and by the corresponding curb on the powers of the President.[2] In the Republican presidential primary campaign of 1976, Ford defeated former California Governor Ronald Reagan for the Republican nomination. He narrowly lost the presidential election to the Democratic challenger, former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, making him the first President who succeeded to office as a result of a mid-term vacancy since Chester A. Arthur not to be elected in his own right.

Following his years as President, Ford remained active in the Republican Party. After experiencing health problems, he died at home on December 26, 2006. Ford lived longer than any other U.S. president – 93 years and 165 days – while his 895-day presidency was the shortest of all presidents who did not die in office.

Early life

Ford was born Leslie Lynch King, Jr. on July 14, 1913, at 3202 Woolworth Avenue in Omaha, Nebraska, where his parents lived with his paternal grandparents. His mother was Dorothy Ayer Gardner and his father was Leslie Lynch King Sr., a wool trader and a son of prominent banker Charles Henry King and Martha Alicia King (née Porter). Dorothy separated from King just sixteen days after her son's birth. She took her son with her to the Oak Park, Illinois, home of her sister Tannisse and brother-in-law, Clarence Haskins James. From there, she moved to the home of her parents, Levi Addison Gardner and Adele Augusta Ayer, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Dorothy and King divorced in December 1913, and she gained full custody of her son. Ford's paternal grandfather Charles Henry King paid child support until shortly before his death in 1930.[3]

Ford later said his biological father had a history of hitting his mother.[4] James M. Cannon, a member of the Ford administration, wrote in a biography of Ford that the Kings' separation and divorce were sparked when, a few days after Ford's birth, Leslie King took a butcher knife and threatened to kill his wife, his infant son, and Ford's nursemaid. Ford later told confidantes that his father had first hit his mother on their honeymoon for smiling at another man.[5]

After two and a half years with her parents, on February 1, 1916, Dorothy married Gerald Rudolff Ford, a salesman in a family-owned paint and varnish company. They then called her son Gerald Rudolff Ford, Jr. The future president was never formally adopted, and did not legally change his name until December 3, 1935; he also used a more conventional spelling of his middle name.[6] He was raised in Grand Rapids with his three half-brothers from his mother's second marriage: Thomas Gardner "Tom" Ford (1918–1995), Richard Addison "Dick" Ford (1924–2015), and James Francis "Jim" Ford (1927–2001).[7]

Ford also had three half-siblings from the second marriage of Leslie King, Sr., his biological father: Marjorie King (1921–1993), Leslie Henry King (1923–1976), and Patricia Jane King (born 1925). They never saw one another as children and he did not know them at all. Ford was not aware of his biological father until he was 17, when his parents told him about the circumstances of his birth. That year his biological father, whom Ford described as a "carefree, well-to-do man who didn't really give a damn about the hopes and dreams of his firstborn son", approached Ford while he was waiting tables in a Grand Rapids restaurant. The two "maintained a sporadic contact" until Leslie King, Sr.'s death in 1941.[4][8]

Ford said, "My stepfather was a magnificent person and my mother equally wonderful. So I couldn't have written a better prescription for a superb family upbringing."[9]

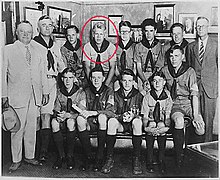

Ford was involved in the Boy Scouts of America, and earned that program's highest rank, Eagle Scout.[10] He is the only Eagle Scout to have ascended to the U.S. Presidency.[10]

Ford attended Grand Rapids South High School, where he was a star athlete and captain of the football team.[11] In 1930, he was selected to the All-City team of the Grand Rapids City League. He also attracted the attention of college recruiters.[9]

College and law school

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Attending the University of Michigan as an undergraduate, Ford became a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Omicron chapter) and washed dishes at his fraternity house to earn money for college expenses.

Ford played center, linebacker, and long snapper for the school's football team,[12] and helped the Wolverines in two undefeated seasons and national titles in 1932 and 1933. The team suffered a steep decline in his 1934 senior year, however, winning only one game. Ford was the team's star nonetheless. After a game during which Michigan held heavily favored Minnesota (the eventual national champion) to a scoreless tie in the first half, assistant coach Bennie Oosterbaan later said, "When I walked into the dressing room at halftime, I had tears in my eyes I was so proud of them. Ford and [Cedric] Sweet played their hearts out. They were everywhere on defense." Ford later recalled, "During 25 years in the rough-and-tumble world of politics, I often thought of the experiences before, during, and after that game in 1934. Remembering them has helped me many times to face a tough situation, take action, and make every effort possible despite adverse odds." His teammates later voted Ford their most valuable player, with one assistant coach noting, "They felt Jerry was one guy who would stay and fight in a losing cause."[13]

During Ford's senior year, a controversy developed when the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets refused to play a scheduled game if a black player named Willis Ward took the field. Even after protests from students, players and alumni, university officials opted to keep Ward out of the game. Ford was Ward's best friend on the team and they roomed together while on road trips. Ford reportedly threatened to quit the team in response to the university's decision, but eventually agreed to play against Georgia Tech when Ward personally asked him to play.[14]

In 1934, Ford was selected for the Eastern Team on the Shriner's East West Shrine Game at San Francisco (a benefit for physically disabled children), played on January 1, 1935. As part of the 1935 Collegiate All-Star football team, Ford played against the Chicago Bears in the Chicago College All-Star Game at Soldier Field.[15] In honor of his athletic accomplishments and his later political career, the University of Michigan retired Ford's No. 48 jersey in 1994. With the blessing of the Ford family, it was placed back into circulation in 2012 as part of the Michigan Football Legends program and issued to sophomore linebacker Desmond Morgan before a home game against Illinois on October 13.[16]

Ford remained interested in football and his school throughout life, occasionally attending games. Ford also visited with players and coaches during practices, at one point asking to join the players in the huddle.[17] Ford often had the Naval band play the University of Michigan fight song, The Victors, before state events instead of Hail to the Chief.[18]

Following his graduation in 1935 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics, Ford turned down contract offers from the Detroit Lions and Green Bay Packers of the National Football League. Instead, in September 1935 he took a job as the boxing coach and assistant varsity football coach at Yale University,[19] and applied to its law school.[20]

Ford hoped to attend Yale's law school beginning in 1935. Yale officials at first denied his admission to the law school because of his full-time coaching responsibilities. He spent the summer of 1937 as a student at the University of Michigan Law School[21] and was eventually admitted in the spring of 1938 to Yale Law School.[22] Ford earned his LL.B. degree in 1941 (later amended to Juris Doctor), graduating in the top 25 percent of his class.

While attending Yale Law School, Ford joined a group of students led by R. Douglas Stuart Jr., and signed a petition to enforce the 1939 Neutrality Act. The petition was circulated nationally and was the inspiration for the America First Committee, a group determined to keep the U.S. out of World War II.[23] In the summer of 1940 he worked in Wendell Willkie's presidential campaign.

Ford graduated from law school in 1941 and was admitted to the Michigan bar shortly thereafter. In May 1941, he opened a Grand Rapids law practice with a friend, Philip W. Buchen,[19] who would later serve as Ford's White House counsel.

U.S. Naval Reserve

Ford responded to the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor by enlisting in the navy.[24] He received a commission as ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve on April 13, 1942. On April 20, he reported for active duty to the V-5 instructor school at Annapolis, Maryland. After one month of training, he went to Navy Preflight School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he was one of 83 instructors and taught elementary navigation skills, ordinance, gunnery, first aid, and military drill. In addition, he coached in all nine sports that were offered, but mostly in swimming, boxing and football. During the year he was at the Preflight School, he was promoted to Lieutenant, Junior Grade, on June 2, 1942, and to lieutenant, in March 1943.

Sea duty

After applying for sea duty, Ford was sent in May 1943 to the pre-commissioning detachment for the new aircraft carrier USS Monterey (CVL-26), at New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey. From the ship's commissioning on June 17, 1943, until the end of December 1944, Ford served as the assistant navigator, Athletic Officer, and antiaircraft battery officer on board the Monterey. While he was on board, the carrier participated in many actions in the Pacific Theater with the Third and Fifth Fleets in late 1943 and 1944. In 1943, the carrier helped secure Makin Island in the Gilberts, and participated in carrier strikes against Kavieng, New Ireland in 1943. During the spring of 1944, the Monterey supported landings at Kwajalein and Eniwetok and participated in carrier strikes in the Marianas, Western Carolines, and northern New Guinea, as well as in the Battle of the Philippine Sea.[25] After an overhaul, from September to November 1944, aircraft from the Monterey launched strikes against Wake Island, participated in strikes in the Philippines and Ryukyus, and supported the landings at Leyte and Mindoro.[25]

Although the ship was not damaged by Japanese forces, the Monterey was one of several ships damaged by the typhoon that hit Admiral William Halsey's Third Fleet on December 18–19, 1944. The Third Fleet lost three destroyers and over 800 men during the typhoon. The Monterey was damaged by a fire, which was started by several of the ship's aircraft tearing loose from their cables and colliding on the hangar deck. During the storm, Ford narrowly avoided becoming a casualty himself. As he was going to his battle station on the bridge of the ship in the early morning of December 18, the ship rolled twenty-five degrees, which caused Ford to lose his footing and slide toward the edge of the deck. The two-inch steel ridge around the edge of the carrier slowed him enough so he could roll, and he twisted into the catwalk below the deck. As he later stated, "I was lucky; I could have easily gone overboard."

Ford, serving as General Quarters Officer of the Deck, was ordered to go below to assess the raging fire. He did so safely, and reported his findings back to the ship's commanding officer, Captain Stuart Ingersoll. The ship's crew was able to contain the fire, and the ship got underway again.[26]

After the fire, the Monterey was declared unfit for service, and the crippled carrier reached Ulithi on December 21 before continuing across the Pacific to Bremerton, Washington where it underwent repairs. On December 24, 1944, at Ulithi, Ford was detached from the ship and sent to the Navy Pre-Flight School at Saint Mary's College of California, where he was assigned to the Athletic Department until April 1945. One of his duties was to coach football. From the end of April 1945 to January 1946, he was on the staff of the Naval Reserve Training Command, Naval Air Station, Glenview, Illinois, as the Staff Physical and Military Training Officer. On October 3, 1945, he was promoted to lieutenant commander.

Ford received the following military awards: the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with nine 3⁄16" bronze stars (for operations in the Gilbert Islands, Bismarck Archipelago, Marshall Islands, Asiatic and Pacific carrier raids, Hollandia, Marianas, Western Carolines, Western New Guinea, and the Leyte Operation), the Philippine Liberation Medal with two 3⁄16" bronze stars (for Leyte and Mindoro), and the World War II Victory Medal.[24]

Post-war

In January 1946, Ford was sent to the Separation Center, Great Lakes to be processed out. He was released from active duty under honorable conditions on February 23, 1946. On June 28, 1946, the Secretary of the Navy accepted Ford's resignation from the Naval Reserve.

Marriage and children

On October 15, 1948, at Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids, Ford married Elizabeth Bloomer Warren (1918–2011), a department store fashion consultant. Warren had been a John Robert Powers fashion model and a dancer in the auxiliary troupe of the Martha Graham Dance Company. She had previously been married to and divorced from William G. Warren.

At the time of his engagement, Ford was campaigning for what would be his first of thirteen terms as a member of the United States House of Representatives. The wedding was delayed until shortly before the elections because, as The New York Times reported in a 1974 profile of Betty Ford, "Jerry was running for Congress and wasn't sure how voters might feel about his marrying a divorced ex-dancer."[27]

The couple had four children:

- Michael Gerald, born in 1949

- John Gardner, known as Jack, born in 1951

- Steven Meigs, born in 1956

- Susan Elizabeth, born in 1957

House of Representatives (1949–73)

After returning to Grand Rapids in 1946, Ford became active in local Republican politics, and supporters urged him to take on Bartel J. Jonkman, the incumbent Republican congressman. Military service had changed his view of the world. "I came back a converted internationalist", Ford wrote, "and of course our congressman at that time was an avowed, dedicated isolationist. And I thought he ought to be replaced. Nobody thought I could win. I ended up winning two to one."[9]

During his first campaign in 1948, Ford visited voters at their doorsteps and as they left the factories where they worked.[28] Ford also visited local farms where, in one instance, a wager resulted in Ford spending two weeks milking cows following his election victory.[29]

Ford was a member of the House of Representatives for 25 years, holding the Grand Rapids congressional district seat from 1949 to 1973. It was a tenure largely notable for its modesty. As an editorial in The New York Times described him, Ford "saw himself as a negotiator and a reconciler, and the record shows it: he did not write a single piece of major legislation in his entire career."[30] Appointed to the House Appropriations Committee two years after being elected, he was a prominent member of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. Ford described his philosophy as "a moderate in domestic affairs, an internationalist in foreign affairs, and a conservative in fiscal policy."[31] Ford was known to his colleagues in the House as a "Congressman's Congressman".[32]

In the early 1950s, Ford declined offers to run for either the Senate or the Michigan governorship. Rather, his ambition was to become Speaker of the House.[33]

Warren Commission

On November 29, 1963, Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Ford to the Warren Commission, a special task force set up to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.[34] Ford was assigned to prepare a biography of Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin. According to a 1963 FBI memo released in 2008, Ford was in contact with the FBI throughout his time on the Warren Commission and relayed information to the deputy director, Cartha DeLoach, about the panel's activities.[35][36][37] In the preface to his book, A Presidential Legacy and The Warren Commission, Ford defended the work of the commission and reiterated his support of its conclusions.[38]

House Minority Leader (1965–73)

In 1964, Lyndon Johnson led a landslide victory for his party, securing another term as president and taking 36 seats from Republicans in the House of Representatives. Following the election, members of the Republican caucus looked to select a new Minority Leader. Three members approached Ford to see if he would be willing to serve; after consulting with his family, he agreed. After a closely contested election, Ford was chosen to replace Charles Halleck of Indiana as Minority Leader.[39]

In January 1965, the Republicans had 140 seats in the House compared with the 295 seats held by the Democrats. With that large majority, and a majority in the U.S. Senate, the Johnson Administration proposed and passed a series of programs that was called by Johnson the "Great Society." During the first session of the Eighty-ninth Congress alone, the Johnson Administration submitted 87 bills to Congress, and Johnson signed 84, or 96%, arguably the most successful legislative agenda in Congressional history.[40]

In 1966, criticism over the Johnson Administration's handling of the Vietnam War began to grow, with Ford and Congressional Republicans expressing concern that the United States was not doing what was necessary to win the war. Public sentiment also began to move against Johnson, and the 1966 midterm elections saw a 47-seat swing in favor of the Republicans. This was not enough to give Republicans a majority in the House, but the victory gave Ford the opportunity to prevent the passage of further Great Society programs.[39]

Ford's private criticism of the Vietnam War became public following a speech from the floor of the House, in which he questioned whether the White House had a clear plan to bring the war to a successful conclusion.[39] The speech angered President Johnson, who accused Ford of having played "too much football without a helmet".[39][41]

As Minority Leader in the House, Ford appeared in a popular series of televised press conferences with Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen, in which they proposed Republican alternatives to Johnson's policies. Many in the press jokingly called this "The Ev and Jerry Show."[42] Johnson said at the time, "Jerry Ford is so dumb he can't fart and chew gum at the same time."[43] The press, used to sanitizing LBJ's salty language, reported this as "Gerald Ford can't walk and chew gum at the same time."[44]

After President Nixon was elected in November 1968, Ford's role shifted to being an advocate for the White House agenda. Congress passed several of Nixon's proposals, including the National Environmental Policy Act and the Tax Reform Act of 1969. Another high-profile victory for the Republican minority was the State and Local Fiscal Assistance act. Passed in 1972, the act established a Revenue Sharing program for state and local governments.[45] Ford's leadership was instrumental in shepherding revenue sharing through Congress, and resulted in a bipartisan coalition that supported the bill with 223 votes in favor (compared with 185 against).[39][46]

During the eight years (1965–1973) that Ford served as Minority Leader, he won many friends in the House because of his fair leadership and inoffensive personality.[39]

Vice presidency (1973–74)

On October 10, 1973, Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned and then pleaded no contest to criminal charges of tax evasion and money laundering, part of a negotiated resolution to a scheme in which he accepted $29,500 in bribes while governor of Maryland. According to The New York Times, Nixon "sought advice from senior Congressional leaders about a replacement. The advice was unanimous. 'We gave Nixon no choice but Ford,' House Speaker Carl Albert recalled later".[30]

Ford was nominated to take Agnew's position on October 12, the first time the vice-presidential vacancy provision of the 25th Amendment had been implemented. The United States Senate voted 92 to 3 to confirm Ford on November 27. Only three Senators, all Democrats, voted against Ford's confirmation: Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, Thomas Eagleton of Missouri and William Hathaway of Maine. On December 6, 1973, the House confirmed Ford by a vote of 387 to 35. One hour after the confirmation vote in the House, Ford took the oath of office as Vice President of the United States.

Ford became Vice President as the Watergate scandal was unfolding. On Thursday, August 1, 1974, Chief of Staff Alexander Haig contacted Ford to tell him that "smoking gun" evidence had been found. The evidence left little doubt that President Nixon had been a part of the Watergate cover-up. At the time, Ford and his wife, Betty, were living in suburban Virginia, waiting for their expected move into the newly designated vice president's residence in Washington, D.C. However, "Al Haig [asked] to come over and see me," Ford later said, "to tell me that there would be a new tape released on a Monday, and he said the evidence in there was devastating and there would probably be either an impeachment or a resignation. And he said, 'I'm just warning you that you've got to be prepared, that things might change dramatically and you could become President.' And I said, 'Betty, I don't think we're ever going to live in the vice president's house.'"[9]

Presidency (1974–77)

Swearing-in

When Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Ford assumed the presidency, making him the only person to assume the presidency without having been previously voted into either the presidential or vice presidential office. Immediately after taking the oath of office in the East Room of the White House, he spoke to the assembled audience in a speech broadcast live to the nation.[47] Ford noted the peculiarity of his position: "I am acutely aware that you have not elected me as your president by your ballots, and so I ask you to confirm me as your president with your prayers."[48] He went on to state:

I have not sought this enormous responsibility, but I will not shirk it. Those who nominated and confirmed me as Vice President were my friends and are my friends. They were of both parties, elected by all the people and acting under the Constitution in their name. It is only fitting then that I should pledge to them and to you that I will be the President of all the people.[49]

He also stated:

My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here, the people rule. But there is a higher Power, by whatever name we honor Him, who ordains not only righteousness but love, not only justice, but mercy. ... let us restore the golden rule to our political process, and let brotherly love purge our hearts of suspicion and hate.[50]

A portion of the speech would later be memorialized with a plaque at the entrance to his presidential museum.

On August 20, Ford nominated former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller to fill the vice presidency he had vacated.[51] Rockefeller's top competitor had been George H. W. Bush. Rockefeller underwent extended hearings before Congress, which caused embarrassment when it was revealed he made large gifts to senior aides, such as Henry Kissinger. Although conservative Republicans were not pleased that Rockefeller was picked, most of them voted for his confirmation, and his nomination passed both the House and Senate. Some, including Barry Goldwater, voted against him.[52]

Pardon of Nixon

On September 8, 1974, Ford issued Proclamation 4311, which gave Nixon a full and unconditional pardon for any crimes he might have committed against the United States while President.[53][54][55] In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interests of the country, and that the Nixon family's situation "is a tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."[56]

The Nixon pardon was highly controversial. Critics derided the move and said a "corrupt bargain" had been struck between the men.[9] They said that Ford's pardon was granted in exchange for Nixon's resignation, which had elevated Ford to the presidency. Ford's first press secretary and close friend Jerald terHorst resigned his post in protest after the pardon. According to Bob Woodward, Nixon Chief of Staff Alexander Haig proposed a pardon deal to Ford. He later decided to pardon Nixon for other reasons, primarily the friendship he and Nixon shared.[57] Regardless, historians believe the controversy was one of the major reasons Ford lost the election in 1976, an observation with which Ford agreed.[57] In an editorial at the time, The New York Times stated that the Nixon pardon was a "profoundly unwise, divisive and unjust act" that in a stroke had destroyed the new president's "credibility as a man of judgment, candor and competence".[30] On October 17, 1974, Ford testified before Congress on the pardon. He was the first sitting President since Abraham Lincoln to testify before the House of Representatives.[58][59]

In the months following the pardon, Ford often declined to mention President Nixon by name, referring to him in public as "my predecessor" or "the former president." When, on a 1974 trip to California, White House correspondent Fred Barnes pressed Ford on the matter, Ford replied in surprisingly frank manner: "I just can’t bring myself to do it.”[60]

After Ford left the White House in January 1977, the former President privately justified his pardon of Nixon by carrying in his wallet a portion of the text of Burdick v. United States, a 1915 U.S. Supreme Court decision which stated that a pardon indicated a presumption of guilt, and that acceptance of a pardon was tantamount to a confession of that guilt.[61] In 2001, the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award to Ford for his pardon of Nixon.[62] In presenting the award to Ford, Senator Edward Kennedy said that he had initially been opposed to the pardon of Nixon, but later decided that history had proved Ford to have made the correct decision.[63]

Draft dodgers and deserters

On September 16, shortly after he announced the Nixon pardon, Ford introduced a conditional amnesty program for Vietnam War draft dodgers who had fled to countries such as Canada, and for military deserters, in Presidential Proclamation 4313. The conditions of the amnesty required that those reaffirm their allegiance to the United States and serve two years working in a public service job or a total of two years service for those who had served less than two years of honorable service in the military.[64] The program for the Return of Vietnam Era Draft Evaders and Military Deserters[65] established a Clemency Board to review the records and make recommendations for receiving a Presidential Pardon and a change in Military discharge status. Full pardon for draft dodgers came in the Carter Administration.[66]

Administration officials

Upon assuming office, Ford inherited Nixon's Cabinet. During Ford's brief administration, all members were replaced except Secretary of State Kissinger and Secretary of the Treasury William E. Simon. Ford's dramatic reorganization of his Cabinet in the fall of 1975 has been referred to by political commentators as the "Halloween Massacre". One of Ford's appointees, William Coleman, as Secretary of Transportation, was the second black man to serve in a presidential cabinet (after Robert C. Weaver) and the first appointed in a Republican administration.[67]

Other members of the administration:

- United States National Security Advisor

- Henry Kissinger (1974–1975)

- Brent Scowcroft (1975–1977)

- Director of Central Intelligence

- William Colby (1974–1976)

- George H. W. Bush (1976–1977)

- Press Secretary

- Jerald terHorst (1974)

- Ron Nessen (1974–1977)

- United States Ambassador to the United Nations

- John A. Scali (1974–1975)

- Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1975–1976)

- William Scranton (1976–1977)

Ford selected George H. W. Bush as Chief of the US Liaison Office to the People's Republic of China in 1974, and then Director of the Central Intelligence Agency in late 1975.[68]

Ford's transition chairman and first Chief of Staff was former congressman and ambassador Donald Rumsfeld. In 1975, Rumsfeld was named by Ford as the youngest-ever Secretary of Defense. Ford chose a young Wyoming politician, Richard Cheney, to replace Rumsfeld as his new Chief of Staff; Cheney became the campaign manager for Ford's 1976 presidential campaign.[69]

Midterm elections

The 1974 Congressional midterm elections took place less than three months after Ford assumed office and in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The Democratic Party turned voter dissatisfaction into large gains in the House elections, taking 49 seats from the Republican Party, increasing their majority to 291 of the 435 seats. This was one more than the number needed (290) for a two-thirds majority, the number necessary to override a Presidential veto or to propose a constitutional amendment. Perhaps due in part to this fact, the 94th Congress overrode the highest percentage of vetoes since Andrew Johnson was President of the United States (1865–1869).[70] Even Ford's former, reliably Republican House seat was won by a Democrat, Richard Vander Veen, who defeated Robert VanderLaan. In the Senate elections, the Democratic majority became 61 in the 100-seat body.[71]

Domestic policy

Inflation

The economy was a great concern during the Ford administration. One of the first acts the new president took to deal with the economy was to create, by Executive Order on September 30, 1974, the Economic Policy Board.[72] In October 1974, in response to rising inflation, Ford went before the American public and asked them to "Whip Inflation Now". As part of this program, he urged people to wear "WIN" buttons.[73] At the time, inflation was believed to be the primary threat to the economy, more so than growing unemployment; there was a belief that controlling inflation would help reduce unemployment.[72] To rein in inflation, it was necessary to control the public's spending. To try to mesh service and sacrifice, "WIN" called for Americans to reduce their spending and consumption.[74] On October 4, 1974, Ford gave a speech in front of a joint session of Congress; as a part of this speech he kicked off the "WIN" campaign. Over the next nine days 101,240 Americans mailed in "WIN" pledges.[72] In hindsight, this was viewed as simply a public relations gimmick which had no way of solving the underlying problems.[75] The main point of that speech was to introduce to Congress a one-year, five-percent income tax increase on corporations and wealthy individuals. This plan would also take $4.4 billion out of the budget, bringing federal spending below $300 billion.[76] At the time, inflation was over twelve percent.[77]

Budget

The federal budget ran a deficit every year Ford was President.[78] Despite his reservations about how the program ultimately would be funded in an era of tight public budgeting, Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which established special education throughout the United States. Ford expressed "strong support for full educational opportunities for our handicapped children" according to the official White House press release for the bill signing.[79]

The economic focus began to change as the country sank into the worst recession since the Great Depression four decades earlier.[80] The focus of the Ford administration turned to stopping the rise in unemployment, which reached nine percent in May 1975.[81] In January 1975, Ford proposed a 1-year tax reduction of $16 billion to stimulate economic growth, along with spending cuts to avoid inflation.[76] Ford was criticized greatly for quickly switching from advocating a tax increase to a tax reduction. In Congress, the proposed amount of the tax reduction increased to $22.8 billion in tax cuts and lacked spending cuts.[72] In March 1975, Congress passed, and Ford signed into law, these income tax rebates as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975. This resulted in a federal deficit of around $53 billion for the 1975 fiscal year and $73.7 billion for 1976.[82]

When New York City faced bankruptcy in 1975, Mayor Abraham Beame was unsuccessful in obtaining Ford's support for a federal bailout. The incident prompted the New York Daily News' famous headline "Ford to City: Drop Dead", referring to a speech in which "Ford declared flatly ... that he would veto any bill calling for 'a federal bail-out of New York City'".[83][84] The following month, November 1975, Ford changed his stance and asked Congress to approve federal loans to New York City.[85]

Swine flu

Ford was confronted with a potential swine flu pandemic. In the early 1970s, an influenza strain H1N1 shifted from a form of flu that affected primarily pigs and crossed over to humans. On February 5, 1976, an army recruit at Fort Dix mysteriously died and four fellow soldiers were hospitalized; health officials announced that "swine flu" was the cause. Soon after, public health officials in the Ford administration urged that every person in the United States be vaccinated.[86] Although the vaccination program was plagued by delays and public relations problems, some 25% of the population was vaccinated by the time the program was canceled in December 1976. The vaccine was blamed for twenty-five deaths; more people died from the shots than from the swine flu.[87]

Other domestic issues

Ford was an outspoken supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, issuing Presidential Proclamation no. 4383 in 1975:

In this Land of the Free, it is right, and by nature it ought to be, that all men and all women are equal before the law. Now, therefore, I, Gerald R. Ford, President of the United States of America, to remind all Americans that it is fitting and just to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment adopted by the Congress of the United States of America, in order to secure legal equality for all women and men, do hereby designate and proclaim August 26, 1975, as Women's Equality Day.[88]

As president, Ford's position on abortion was that he supported "a federal constitutional amendment that would permit each one of the 50 States to make the choice".[89] This had also been his position as House Minority Leader in response to the 1973 Supreme Court case of Roe v. Wade, which he opposed.[90] Ford came under criticism for a 60 Minutes interview his wife Betty gave in 1975, in which she stated that Roe v. Wade was a "great, great decision".[91] During his later life, Ford would identify as pro-choice.[92]

Foreign policy

Ford continued the détente policy with both the Soviet Union and China, easing the tensions of the Cold War. Still in place from the Nixon Administration was the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT).[93] The thawing relationship brought about by Nixon's visit to China was reinforced by Ford's December 1975 visit to that communist country.[94] In 1975, the Administration entered into the Helsinki Accords[95] with the Soviet Union, creating the framework of the Helsinki Watch, an independent non-governmental organization created to monitor compliance that later evolved into Human Rights Watch.[96]

Ford attended the inaugural meeting of the Group of Seven (G7) industrialized nations (initially the G5) in 1975 and secured membership for Canada. Ford supported international solutions to issues. "We live in an interdependent world and, therefore, must work together to resolve common economic problems," he said in a 1974 speech.[97]

According to internal White House and Commission documents posted in February 2016 by the National Security Archive at The George Washington University,[98] the Gerald Ford White House significantly altered the final report of the supposedly independent 1975 Rockefeller Commission investigating CIA domestic activities, over the objections of senior Commission staff. The changes included removal of an entire 86-page section on CIA assassination plots and numerous edits to the report by then-deputy White House Chief of Staff Richard Cheney.[99]

Middle East

In the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, two ongoing international disputes developed into crises. The Cyprus dispute turned into a crisis with the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, causing extreme strain within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. In mid-August, the Greek government withdrew Greece from the NATO military structure; in mid-September 1974, the Senate and House of Representatives overwhelmingly voted to halt military aid to Turkey. Ford, concerned with both the effect of this on Turkish-American relations and the deterioration of security on NATO's eastern front, vetoed the bill. A second bill was then passed by Congress, which Ford also vetoed, although a compromise was accepted to continue aid until the end of the year.[2] As Ford expected, Turkish relations were considerably disrupted until 1978.

In the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict, although the initial cease fire had been implemented to end active conflict in the Yom Kippur War, Kissinger's continuing shuttle diplomacy was showing little progress. Ford considered it "stalling" and wrote, "Their [Israeli] tactics frustrated the Egyptians and made me mad as hell."[100] During Kissinger's shuttle to Israel in early March 1975, a last minute reversal to consider further withdrawal, prompted a cable from Ford to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, which included:

I wish to express my profound disappointment over Israel's attitude in the course of the negotiations ... Failure of the negotiation will have a far reaching impact on the region and on our relations. I have given instructions for a reassessment of United States policy in the region, including our relations with Israel, with the aim of ensuring that overall American interests ... are protected. You will be notified of our decision.[101]

On March 24, Ford informed congressional leaders of both parties of the reassessment of the administration policies in the Middle East. "Reassessment", in practical terms, meant canceling or suspending further aid to Israel. For six months between March and September 1975, the United States refused to conclude any new arms agreements with Israel. Rabin notes it was "an innocent-sounding term that heralded one of the worst periods in American-Israeli relations".[102] The announced reassessments upset the American Jewish community and Israel's well-wishers in Congress. On May 21, Ford "experienced a real shock" when seventy-six U.S. senators wrote him a letter urging him to be "responsive" to Israel's request for $2.59 billion in military and economic aid. Ford felt truly annoyed and thought the chance for peace was jeopardized. It was, since the September 1974 ban on arms to Turkey, the second major congressional intrusion upon the President's foreign policy prerogatives.[103] The following summer months were described by Ford as an American-Israeli "war of nerves" or "test of wills".[104] After much bargaining, the Sinai Interim Agreement (Sinai II), was formally signed on September 1, and aid resumed.

Vietnam

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the continued Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the Paris Peace Accords, signed on January 27, 1973. The accords declared a cease fire across both North and South Vietnam, and required the release of American prisoners of war. The agreement guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam and, like the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for national elections in the North and South. The Paris Peace Accords stipulated a sixty-day period for the total withdrawal of U.S. forces.[105]

The accords had been negotiated by United States National Security Advisor Kissinger and North Vietnamese politburo member Lê Đức Thọ. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu was not involved in the final negotiations, and publicly criticized the proposed agreement. However, anti-war pressures within the United States forced Nixon and Kissinger to pressure Thieu to sign the agreement and enable the withdrawal of American forces. In multiple letters to the South Vietnamese president, Nixon had promised that the United States would defend Thieu's government, should the North Vietnamese violate the accords.[106]

In December 1974, months after Ford took office, North Vietnamese forces invaded the province of Phuoc Long. General Trần Văn Trà sought to gauge any South Vietnamese or American response to the invasion, as well as to solve logistical issues, before proceeding with the invasion.[107]

As North Vietnamese forces advanced, Ford requested Congress approve a $722 million aid package for South Vietnam, funds that had been promised by the Nixon administration. Congress voted against the proposal by a wide margin.[93] Senator Jacob K. Javits offered "...large sums for evacuation, but not one nickel for military aid".[93] President Thieu resigned on April 21, 1975, publicly blaming the lack of support from the United States for the fall of his country.[108] Two days later, on April 23, Ford gave a speech at Tulane University. In that speech, he announced that the Vietnam War was over "...as far as America is concerned".[106] The announcement was met with thunderous applause.[106]

1,373 U.S. citizens and 5,595 Vietnamese and third country nationals were evacuated from the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon during Operation Frequent Wind. In that operation, military and Air America helicopters took evacuees to U.S. Navy ships off-shore during an approximately 24-hour period on April 29 to 30, 1975, immediately preceding the fall of Saigon. During the operation, so many South Vietnamese helicopters landed on the vessels taking the evacuees that some were pushed overboard to make room for more people. Other helicopters, having nowhere to land, were deliberately crash landed into the sea after dropping off their passengers, close to the ships, their pilots bailing out at the last moment to be picked up by rescue boats.[109]

Many of the Vietnamese evacuees were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. The 1975 Act appropriated $455 million toward the costs of assisting the settlement of Indochinese refugees.[110] In all, 130,000 Vietnamese refugees came to the United States in 1975. Thousands more escaped in the years that followed.[111]

Mayaguez and Panmunjom

North Vietnam's victory over the South led to a considerable shift in the political winds in Asia, and Ford administration officials worried about a consequent loss of U.S. influence there. The administration proved it was willing to respond forcefully to challenges to its interests in the region on two occasions, once when Khmer Rouge forces seized an American ship in international waters and again when American military officers were killed in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea.[112]

The first crisis was the Mayaguez incident. In May 1975, shortly after the fall of Saigon and the Khmer Rouge conquest of Cambodia, Cambodians seized the American merchant ship Mayaguez in international waters.[113] Ford dispatched Marines to rescue the crew, but the Marines landed on the wrong island and met unexpectedly stiff resistance just as, unknown to the U.S., the Mayaguez sailors were being released. In the operation, two military transport helicopters carrying the Marines for the assault operation were shot down, and 41 U.S. servicemen were killed and 50 wounded while approximately 60 Khmer Rouge soldiers were killed.[114] Despite the American losses, the operation was seen as a success in the United States and Ford enjoyed an 11-point boost in his approval ratings in the aftermath.[115] The Americans killed during the operation became the last to have their names inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington, D.C.

Some historians have argued that the Ford administration felt the need to respond forcefully to the incident because it was construed as a Soviet plot.[116] But work by Andrew Gawthorpe, published in 2009, based on an analysis of the administration's internal discussions, shows that Ford's national security team understood that the seizure of the vessel was a local, and perhaps even accidental, provocation by an immature Khmer government. Nevertheless, they felt the need to respond forcefully to discourage further provocations by other Communist countries in Asia.[117]

The second crisis, known as the axe murder incident, occurred at Panmunjom, a village which stands in the DMZ between the two Koreas. At the time, this was the only part of the DMZ where forces from the North and the South came into contact with each other. Encouraged by U.S. difficulties in Vietnam, North Korea had been waging a campaign of diplomatic pressure and minor military harassment to try and convince the U.S. to withdraw from South Korea.[118] Then, in August 1976, North Korean forces killed two U.S. officers and injured South Korean guards who were engaged in trimming a tree in Panmunjom's Joint Security Area. The attack coincided with a meeting of the Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in Colombo, Sri Lanka, at which Kim Jong-il, the son of North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, presented the incident as an example of American aggression, helping secure the passage of a motion calling for a U.S. withdrawal from the South.[119]

At administration meetings, Kissinger voiced the concern that the North would see the U.S. as "the paper tigers of Saigon" if they did not respond, and Ford agreed with that assessment. After mulling various options the Ford administration decided that it was necessary to respond with a major show of force. A large number of ground forces went to cut down the tree, while at the same time the air force was deployed, which included B-52 bomber flights over Panmunjom. The North Korean government backed down and allowed the tree-cutting to go ahead, and later issued an unprecedented official apology.[120]

Indonesian invasion of East Timor

East Timor's decolonization due to political instability in Portugal saw Indonesia posture to annex the new state in 1975. Just hours before the Indonesian invasion of East Timor (now Timor Leste) on December 7, 1975, Ford and Kissinger had visited Indonesian President Suharto in Jakarta and guaranteed American compliance with the Indonesian operation. Suharto had been a key supporter of American influence in Indonesia and Southeast Asia and Ford did not desire to place pressure on the American-Indonesian relationship.[121]

Under Ford, a policy of arms sales to the Suharto regime began in 1975, before the invasion. "Roughly 90%" of the Indonesian army's weapons at the time of East Timor's invasion were provided by the U.S. according to George H. Aldrich, a former State Department deputy legal advisor.[122] Post-invasion, Ford's military aid averaged about $30 million annually throughout East Timor's occupation, and arms sales increased exponentially under President Carter. This policy continued until 1999.[123]

Assassination attempts

Ford faced two assassination attempts during his presidency. In Sacramento, California, on September 5, 1975, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a follower of Charles Manson, pointed a Colt .45-caliber handgun at Ford.[124] As Fromme pulled the trigger, Larry Buendorf,[125] a Secret Service agent, grabbed the gun, and Fromme was taken into custody. She was later convicted of attempted assassination of the President and was sentenced to life in prison; she was paroled on August 14, 2009.[126]

In reaction to this attempt, the Secret Service began keeping Ford at a more secure distance from anonymous crowds, a strategy that may have saved his life seventeen days later. As he left the St. Francis Hotel in downtown San Francisco, Sara Jane Moore, standing in a crowd of onlookers across the street, pointed her .38-caliber revolver at him.[127] Moore fired a single round but missed because the sights were off. Just before she fired a second round, retired Marine Oliver Sipple grabbed at the gun and deflected her shot; the bullet struck a wall about six inches above and to the right of Ford's head, then ricocheted and hit a taxi driver, who was slightly wounded. Moore was later sentenced to life in prison. She was paroled on December 31, 2007, after serving 32 years.[128]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

In 1975, Ford appointed John Paul Stevens as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States to replace retiring Justice William O. Douglas. Stevens had been a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, appointed by President Nixon.[129] During his tenure as House Republican leader, Ford had led efforts to have Douglas impeached.[130] After being confirmed, Stevens eventually disappointed some conservatives by siding with the Court's liberal wing regarding the outcome of many key issues.[131] Nevertheless, in 2005 Ford praised Stevens. "He has served his nation well," Ford said of Stevens, "with dignity, intellect and without partisan political concerns."[132]

Other judicial appointments

Ford appointed 11 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 50 judges to the United States district courts.[133]

1976 presidential election

Ford reluctantly agreed to run for office in 1976, but first he had to counter a challenge for the Republican party nomination. Former Governor of California Ronald Reagan and the party's conservative wing faulted Ford for failing to do more in South Vietnam, for signing the Helsinki Accords, and for negotiating to cede the Panama Canal. (Negotiations for the canal continued under President Carter, who eventually signed the Torrijos–Carter Treaties.) Reagan launched his campaign in autumn of 1975 and won numerous primaries, including North Carolina, Texas, Indiana, and California, but failed to get a majority of delegates; Reagan withdrew from the race at the Republican Convention in Kansas City, Missouri. The conservative insurgency did lead to Ford dropping the more liberal Vice President Nelson Rockefeller in favor of U.S. Senator Bob Dole of Kansas.[134]

In addition to the pardon dispute and lingering anti-Republican sentiment, Ford had to counter a plethora of negative media imagery. Chevy Chase often did pratfalls on Saturday Night Live, imitating Ford, who had been seen stumbling on two occasions during his term. As Chase commented, "He even mentioned in his own autobiography it had an effect over a period of time that affected the election to some degree."[135]

Ford's 1976 election campaign benefitted from his being an incumbent president during several anniversary events held during the period leading up to the United States Bicentennial. The Washington, D.C. fireworks display on the Fourth of July was presided over by the President and televised nationally.[136] On July 7, 1976, the President and First Lady served as hosts at a White House state dinner for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of the United Kingdom, which was televised on the Public Broadcasting Service network. The 200th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts gave Ford the opportunity to deliver a speech to 110,000 in Concord acknowledging the need for a strong national defense tempered with a plea for "reconciliation, not recrimination" and "reconstruction, not rancor" between the United States and those who would pose "threats to peace".[137] Speaking in New Hampshire on the previous day, Ford condemned the growing trend toward big government bureaucracy and argued for a return to "basic American virtues".[138]

Democratic nominee and former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter campaigned as an outsider and reformer, gaining support from voters dismayed by the Watergate scandal and Nixon pardon. After the Democratic National Convention, he held a huge 33-point lead over Ford in the polls. However, as the campaign continued, the race tightened, and, by election day, the polls showed the race as too close to call. There were three main events in the fall campaign. Most importantly, Carter repeated a promise of a "blanket pardon" for Christian and other religious refugees, and also all Vietnam War draft dodgers (Ford had only issued a conditional amnesty) in response to a question on the subject posed by a reporter during the presidential debates, an act which froze Ford's poll numbers in Ohio, Wisconsin, Hawaii, and Mississippi. (Ford had needed to shift just 11,000 votes in Ohio plus one of the other three in order to win.) It was the first act signed by Carter, on January 20, 1977. Earlier, Playboy magazine had published a controversial interview with Carter; in the interview Carter admitted to having "lusted in my heart" for women other than his wife, which cut into his support among women and evangelical Christians. Also, on September 24, Ford performed well in what was the first televised presidential debate since 1960. Polls taken after the debate showed that most viewers felt that Ford was the winner. Carter was also hurt by Ford's charges that he lacked the necessary experience to be an effective national leader, and that Carter was vague on many issues.

Televised presidential debates were reintroduced for the first time since the 1960 election. As such, Ford became the first incumbent president to participate in one. Carter later attributed his victory in the election to the debates, saying they "gave the viewers reason to think that Jimmy Carter had something to offer". The turning point came in the second debate when Ford blundered by stating, "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford Administration." Ford also said that he did not "believe that the Poles consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union".[139] In an interview years later, Ford said he had intended to imply that the Soviets would never crush the spirits of eastern Europeans seeking independence. However, the phrasing was so awkward that questioner Max Frankel was visibly incredulous at the response.[140] As a result of this blunder, and Carter's promise of a full presidential pardon for political refugees from the Vietnam era during the presidential debates, Ford's surge stalled and Carter was able to maintain a slight lead in the polls.

In the end, Carter won the election, receiving 50.1% of the popular vote and 297 electoral votes compared with 48.0% and 240 electoral votes for Ford. The election was close enough that had fewer than 25,000 votes shifted in Ohio and Wisconsin – both of which neighbored his home state – Ford would have won the electoral vote with 276 votes to 261 for Carter.[141] Though he lost, in the three months between the Republican National Convention and the election Ford had managed to close what was once an alleged 33-point Carter lead to a 2-point margin. Ford carried 27 states versus 23 carried by Carter.

Had Ford won the election, the provisions of the 22nd Amendment would have disqualified him from running in 1980, because he had served more than two years of Nixon's remaining term.

Post-presidential years (1977–2006)

Activity

The Nixon pardon controversy eventually subsided. Ford's successor, Jimmy Carter, opened his 1977 inaugural address by praising the outgoing President, saying, "For myself and for our Nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land."[142]

Ford remained relatively active in the years after his presidency. He continued to make appearances at events of historical and ceremonial significance to the nation, such as presidential inaugurals and memorial services. In January 1977, he became the president of Eisenhower Fellowships in Philadelphia, then served as the chairman of its board of trustees from 1980 to 1986.[143] Later in 1977, he reluctantly agreed to be interviewed by James M. Naughton, a New York Times journalist who was given the assignment to write the former President's advance obituary, an article that would be updated prior to its eventual publication.[144] In 1979, Ford published his autobiography, A Time to Heal (Harper/Reader's Digest, 454 pages). A review in Foreign Affairs described it as, "Serene, unruffled, unpretentious, like the author. This is the shortest and most honest of recent presidential memoirs, but there are no surprises, no deep probings of motives or events. No more here than meets the eye."[145]

During the term of office of his successor, Jimmy Carter, Ford received monthly briefs by President Carter's senior staff on international and domestic issues, and was always invited to lunch at the White House whenever he was in Washington, D.C. Their close friendship developed after Carter had left office, with the catalyst being their trip together to the funeral of Anwar el-Sadat in 1981.[146] Until Ford's death, Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, visited the Fords' home frequently.[147] Ford and Carter served as honorary co-chairs of the National Commission on Federal Election Reform in 2001 and of the Continuity of Government Commission in 2002.

Like Presidents Carter, George H. W. Bush, and Clinton, Ford was an honorary co-chair of the Council for Excellence in Government, a group dedicated to excellence in government performance, which provides leadership training to top federal employees.

In retirement Ford also devoted much time to his love of golf, often playing both privately and in public events with comedian Bob Hope, a longtime friend. In 1977, he shot a hole in one during a Pro-am held in conjunction with the Danny Thomas Memphis Classic at Colonial Country Club in Memphis, Tennessee. He hosted the Jerry Ford Invitational in Vail, Colorado from 1977 to 1996.

Ford considered a run for the Republican nomination in 1980, foregoing numerous opportunities to serve on corporate boards to keep his options open for a rematch with Carter. Ford attacked Carter's conduct of the SALT II negotiations and foreign policy in the Middle East and Africa. Many have argued that Ford also wanted to exorcise his image as an "Accidental President" and to win a term in his own right. Ford also believed the more conservative Ronald Reagan would be unable to defeat Carter and would hand the incumbent a second term. Ford was encouraged by his former Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger as well as Jim Rhodes of Ohio and Bill Clements of Texas to make the race. On March 15, 1980, Ford announced that he would forgo a run for the Republican nomination, vowing to support the eventual nominee.

After securing the Republican nomination in 1980, Ronald Reagan considered his former rival Ford as a potential vice-presidential runningmate, but negotiations between the Reagan and Ford camps at the Republican National Convention were unsuccessful. Ford conditioned his acceptance on Reagan's agreement to an unprecedented "co-presidency",[148] giving Ford the power to control key executive branch appointments (such as Kissinger as Secretary of State and Alan Greenspan as Treasury Secretary). After rejecting these terms, Reagan offered the vice-presidential nomination instead to George H. W. Bush.[149] Ford did appear in a campaign commercial for the Reagan-Bush ticket, in which he declared that the country would be "better served by a Reagan presidency rather than a continuation of the weak and politically expedient policies of Jimmy Carter".[150]

After his presidency, Ford joined the American Enterprise Institute as a distinguished fellow. He founded the annual AEI World Forum in 1982. Ford was awarded an honorary doctorate at Central Connecticut State University[151] on March 23, 1988.

After leaving the White House, Ford and his wife moved to Denver, Colorado. Ford successfully invested in oil with Marvin Davis, which later provided an income for Ford's children.[152]

In 1987, Ford testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in favor of District of Columbia Circuit Court judge and former Solicitor General Robert Bork after Bork was nominated by President Reagan to be an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.[153] Bork's nomination was rejected by a vote of 58-42.[154]

In 1987 Ford's Humor and the Presidency, a book of humorous political anecdotes, was published.

By 1988, Ford was a member of several corporate boards including Commercial Credit, Nova Pharmaceutical, The Pullman Company, Tesoro Petroleum, and Tiger International, Inc.[155] Ford also became an honorary director of Citigroup, a position he held till his death.[156]

In 1977, Ford established the Gerald R. Ford Institute of Public Policy at Albion College in Albion, Michigan, to give undergraduates training in public policy. In April 1981, he opened the Gerald R. Ford Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on the north campus of his alma mater, the University of Michigan,[157] followed in September by the Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids.[158][159]

In April 1991, Ford joined former presidents Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Jimmy Carter, in supporting the Brady Bill.[160] Three years later, he wrote to the U.S. House of Representatives, along with Carter and Reagan, in support of the assault weapons ban.[161]

In October 2001, Ford broke with conservative members of the Republican Party by stating that gay and lesbian couples "ought to be treated equally. Period." He became the highest ranking Republican to embrace full equality for gays and lesbians, stating his belief that there should be a federal amendment outlawing anti-gay job discrimination and expressing his hope that the Republican Party would reach out to gay and lesbian voters.[162] He also was a member of the Republican Unity Coalition, which The New York Times described as "a group of prominent Republicans, including former President Gerald R. Ford, dedicated to making sexual orientation a non-issue in the Republican Party".[163]

On November 22, 2004, New York Republican Governor George Pataki named Ford and the other living former Presidents (Carter, George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton) as honorary members of the board rebuilding the World Trade Center.

In a pre-recorded embargoed interview with Bob Woodward of The Washington Post in July 2004, Ford stated that he disagreed "very strongly" with the Bush administration's choice of Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction as justification for its decision to invade Iraq, calling it a "big mistake" unrelated to the national security of the United States and indicating that he would not have gone to war had he been President. The details of the interview were not released until after Ford's death, as he requested.[164][165]

Health problems

Ford suffered two minor strokes at the 2000 Republican National Convention, but made a quick recovery after being admitted to Hahnemann University Hospital.[166][167] In January 2006, he spent 11 days at the Eisenhower Medical Center near his residence at Rancho Mirage, California, for treatment of pneumonia.[168] On April 23, 2006, President George W. Bush visited Ford at his home in Rancho Mirage for a little over an hour. This was Ford's last public appearance and produced the last known public photos, video footage, and voice recording.

While vacationing in Vail, Colorado, Ford was hospitalized for two days in July 2006 for shortness of breath.[169] On August 15 he was admitted to St. Mary's Hospital of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for testing and evaluation. On August 21, it was reported that he had been fitted with a pacemaker. On August 25, he underwent an angioplasty procedure at the Mayo Clinic. On August 28, Ford was released from the hospital and returned with his wife Betty to their California home. On October 13, he was scheduled to attend the dedication of a building of his namesake, the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, but due to poor health and on the advice of his doctors he did not attend. The previous day, Ford had entered the Eisenhower Medical Center for undisclosed tests; he was released on October 16.[170] By November 2006, he was confined to a bed in his study.[171]

Death and legacy

Ford died on December 26, 2006, at his home in Rancho Mirage, California, of arteriosclerotic cerebrovascular disease and diffuse arteriosclerosis. He had end-stage coronary artery disease and severe aortic stenosis and insufficiency, caused by calcific alteration of one of his heart valves.[172] He was 93. Ford died on the 34th anniversary of President Harry Truman's death; he was the last surviving member of the Warren Commission.[173]

On December 30, 2006, Ford became the 11th U.S. President to lie in state. A state funeral and memorial services was held at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on January 2, 2007. After the service, Ford was interred at his Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.[174]

Scouting was so important to Ford that his family asked that Scouts participate in his funeral. A few selected Scouts served as ushers inside the National Cathedral. About 400 Eagle Scouts were part of the funeral procession, where they formed an honor guard as the casket went by in front of the museum.[175]

Ford selected the song to be played during his funeral procession at the U.S. Capitol.[176] After his death in December 2006, the University of Michigan Marching Band played the school's fight song for him one final time, for his last ride from the Gerald R. Ford Airport in Grand Rapids, Michigan.[177]

The State of Michigan commissioned and submitted a statue of Ford to the National Statuary Hall Collection, replacing Zachariah Chandler. It was unveiled on May 3, 2011 in the Capitol Rotunda. On the proper right side is inscribed a quotation from a tribute by Thomas P. "Tip" O'Neill, Speaker of the House at the end of Ford's presidency: "God has been good to America, especially during difficult times. At the time of the Civil War, he gave us Abraham Lincoln. And at the time of Watergate, he gave us Gerald Ford—the right man at the right time who was able to put our nation back together again." On the proper left side are words from Ford's swearing-in address: "Our constitution works. Our great republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule."

Ford's wife, Betty Ford, died on July 8, 2011.[178] Like her husband, she was 93 years old when she died.

Longevity

On November 12, 2006, upon surpassing Ronald Reagan's lifespan, Ford released his last public statement:

The length of one's days matters less than the love of one's family and friends. I thank God for the gift of every sunrise and, even more, for all the years He has blessed me with Betty and the children; with our extended family and the friends of a lifetime. That includes countless Americans who, in recent months, have remembered me in their prayers. Your kindness touches me deeply. May God bless you all and may God bless America.[179]

Ford's age at the time of his death was 93 years and 165 days, making him the longest-lived U.S. President, his lifespan being 45 days longer than Ronald Reagan's.[180][181] He was the third-longest-lived Vice President, falling short only of John Nance Garner, 98, and Levi P. Morton, 96. Ford also had the third-longest post-presidency (29 years and 11 months) after Jimmy Carter (43 years, 11 months and counting) and Herbert Hoover (31 years and 7 months).

Public image

Ford was the only person to hold the presidential office without being elected as either president or vice-president. The choice of Ford to fulfill Spiro Agnew's vacated role as vice president was based on Ford's reputation for openness and honesty.[182] "In all the years I sat in the House, I never knew Mr. Ford to make a dishonest statement nor a statement part-true and part-false. He never attempted to shade a statement, and I never heard him utter an unkind word," said Martha Griffiths.[183]

The trust the American people had in him was rapidly and severely tarnished by his pardon of Nixon.[183] Nonetheless, many grant in hindsight that he had respectably discharged with considerable dignity a great responsibility that he had not sought.[183] His subsequent loss to Carter in 1976 has come to be seen as an honorable sacrifice he made for the nation.[182]

In spite of his athletic record and remarkable career accomplishments, Ford acquired a reputation as a clumsy, likable, and simple-minded Everyman. An incident in 1975, when he tripped while exiting the presidential jet in Austria, was famously and repeatedly parodied by Chevy Chase, cementing Ford's image as a klutz.[183][184][185] Pieces of Ford's common Everyman image have also been attributed to Ford's inevitable comparison to Nixon, as well as his perceived Midwestern stodginess and self-deprecation.[182]

Civic and Fraternal Organizations

Ford was a member of several civic organizations, including the Junior Chamber of Commerce (Jaycees), American Legion, AMVETS, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, Sons of the Revolution,[186] and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Freemasonry

Ford was initiated into Freemasonry on September 30, 1949.[187] He later said in 1975, "When I took my obligation as a master mason—incidentally, with my three younger brothers—I recalled the value my own father attached to that order. But I had no idea that I would ever be added to the company of the Father of our Country and 12 other members of the order who also served as Presidents of the United States."[188] Ford was made a 33° Scottish Rite Mason on September 26, 1962.[189] In April 1975, Ford was elected by a unanimous vote Honorary Grand Master of the International Supreme Council, Order of DeMolay, a position in which he served until January 1977.[190] Ford received the degrees of York Rite Masonry (Chapter and Council degrees) in a special ceremony in the Oval Office on January 11, 1977, during his term as President of the United States.[191]

Honors

Ford received the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award in May 1970, as well as the Silver Buffalo Award, from the Boy Scouts of America. In 1974, he also received the highest distinction of the Scout Association of Japan, the Golden Pheasant Award.[192] In 1985, he received the 1985 Old Tom Morris Award from the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America, GCSAA's highest honor.[193] In 1992, the U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation awarded Ford its Lone Sailor Award for his naval service and his subsequent government service. In 1999, Ford was honored with a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars.[194] Also in 1999, Ford was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Bill Clinton.[195] In 2001, he was presented with the John F. Kennedy Profiles in Courage Award for his decision to pardon Richard Nixon to stop the agony America was experiencing over Watergate.[196]

The following were named after Ford:

- The Ford House Office Building in the U.S. Capitol Complex, formerly House Annex 2.

- Gerald R. Ford Freeway (Nebraska)

- Gerald R. Ford Freeway (Michigan)

- Gerald Ford Memorial Highway, I-70 in Eagle County, Colorado

- Gerald R. Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Gerald R. Ford Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan

- Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan

- Gerald R. Ford Institute of Public Policy, Albion College

- USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78)

- Gerald R. Ford Middle School, Grand Rapids, Michigan[197]

- President Gerald R. Ford Park in Alexandria, Virginia, located in the neighborhood where Ford lived while serving as a Representative and Vice President

- President Ford Field Service Council, Boy Scouts of America The council where he was awarded the rank of Eagle Scout. Serves 25 counties in Western and Northern Michigan with its headquarters located in Grand Rapids, Michigan.[198]

See also

- List of Freemasons

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of Presidents of the United States by previous experience

- Presidents of the United States on U.S. postage stamps

References

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. xxiii, 301. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ a b George Lenczowski (1990). American Presidents, and the Middle East. Duke University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0-8223-0972-6.

- ^ Young, Jeff C. (1997). The Fathers of American Presidents. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-0182-6.

- ^ a b Funk, Josh (December 27, 2006). "Nebraska-born Ford Left State as Infant". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ Cannon, James. "Gerald R. Ford". Character Above All. Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ "Gerald R. Ford Genealogical Information". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum. University of Texas. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ "Richard Ford remembered as active steward of President Gerald Ford's legacy". MLive. March 20, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ "A Common Man on an Uncommon Climb" (PDF). The New York Times. August 19, 1976. p. 28. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Kunhardt Jr., Phillip (1999). Gerald R. Ford "Healing the Nation". New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 79–85. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ a b Townley, Alvin (2007) [December 26, 2006]. Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 12–13 and 87. ISBN 0-312-36653-1. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ "Investigatory Records on Gerald Ford, Applicant for a Commission" (PDF). Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. December 30, 1941. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wertheimer, Linda (December 27, 2006). "Special Report: Former President Gerald Ford Dies; Sought to Heal Nation Disillusioned by Watergate Scandal". National Public Radio. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ Perry, Will (1974). "No Cheers From the Alumni". The Wolverines: A Story of Michigan Football (PDF). Huntsville, Alabama: The Strode Publishers. pp. 150–152. ISBN 0-87397-055-1. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Kruger, Brian; Moorehouse, Buddy (August 9, 2012). "Willis Ward, Gerald Ford and Michigan Football's darkest day". The Detroit News. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Greene, J.R. (1995). The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford (American Presidency Series). University Press of Kansas. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7006-0638-2.

- ^ "Ford Named Michigan Football Legend; Morgan to Wear No. 48 Jersey".

- ^ "Clumsy image aside, Ford was Accomplished Athlete". Los Angeles Times. December 28, 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2009.