Gregg Allman

Gregg Allman | |

|---|---|

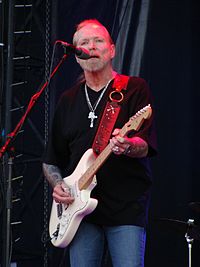

Allman performing in 1975 | |

| Born | Gregory LeNoir Allman December 8, 1947 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | May 27, 2017 (aged 69) Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Complications from liver cancer |

| Resting place | Rose Hill Cemetery |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1960–2017 |

| Spouse(s) |

Shelley Jefts

(m. 1971; div. 1972)Janice Mulkey

(m. 1973; div. 1974)Julie Bindas

(m. 1979; div. 1984)Danielle Galliano

(m. 1989; div. 1994)Stacey Fountain

(m. 2001; div. 2008)Shannon Williams (m. 2017) |

| Children | 5; including Devon and Elijah Blue |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Website | www |

Gregory LeNoir "Gregg" Allman (December 8, 1947 – May 27, 2017) was an American musician, singer, keyboardist and songwriter best known for performing in the Allman Brothers Band. He was born and spent much of his childhood in Nashville, Tennessee, before relocating to Daytona Beach, Florida. He and his brother, Duane Allman, developed an interest in music in their teens, and began performing in the Allman Joys in the mid-1960s. In 1967, they relocated to Los Angeles and were renamed the Hour Glass, releasing two albums for Liberty Records.

In 1969, he and Duane regrouped to form the Allman Brothers Band, which settled in Macon, Georgia. The Allman Brothers Band began to reach mainstream success by the early 1970s, with their live album At Fillmore East representing a commercial and artistic breakthrough. Shortly thereafter, Duane was killed in a motorcycle crash in 1971. The following year, the band's bassist, Berry Oakley, was also killed in a motorcycle accident very close to the location of Duane's wreck. Their 1973 album Brothers and Sisters became their biggest hit.

Internal turmoil took over the group, leading to a breakup after Allman was forced to testify against his road manager Scooter Herring in 1975. Allman next pursued a solo career, releasing his debut album Laid Back the same year. Allman was married to pop star Cher for the rest of the decade, while he continued his solo career with the Gregg Allman Band. After a brief Allman Brothers reunion and a decade of little activity, he reached an unexpected peak with the hit single "I'm No Angel" in 1987. After two more solo albums, the Allman Brothers regrouped for a third and final time in 1989, and continued performing until 2014. He released his most recent solo album, Low Country Blues, in 2011, and his last, Southern Blood, is set to be released in 2017.

For his work in music, Allman was referred to as a Southern rock pioneer[1] and received numerous awards, including several Grammys; he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. His distinctive voice placed him in 70th place in the Rolling Stone list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time".[2] Allman released an autobiography, My Cross to Bear, in 2012.

Early life

Allman was born Gregory LeNoir Allman at St. Thomas Hospital on December 8, 1947 in Nashville, Tennessee, to Willis Turner Allman and Geraldine Robbins Allman.[3] The couple had met during World War II in Raleigh, North Carolina, when Allman was on leave from the U.S. Army, and were later married. They moved to Vanleer, Tennessee, in 1945.[citation needed] Their first child, Duane Allman, was born in Nashville in 1946.

On December 26, 1949, Willis Allman, an Army lieutenant, offered a hitchhiker a ride home and was subsequently shot and killed in Norfolk, Virginia.[4][5] Geraldine moved to Nashville with her two sons, and she never remarried.[6] Lacking money to support her children, she enrolled in college to become a Certified Public Accountant (CPA)—state laws at the time, according to her son, required students to live on-campus.[7] As a result, Gregg and his older brother were sent to Castle Heights Military Academy in nearby Lebanon.[3] A young Gregg interpreted these actions as evidence of his mother's dislike for him, though he later came to understand the reality: "She was actually sacrificing everything she possibly could—she was working around the clock, getting by just by a hair, so as to not send us to an orphanage, which would have been a living hell."[8]

While his brother adapted to his surroundings with a defiant attitude, Allman felt largely depressed at the school. With little to do, he studied often and developed an interest in medicine—had he not gone into music, he hoped to become a dentist.[9] He was rarely hazed at Castle Heights as his brother protected him, but often suffered beatings from instructors when he received poor grades.[10] The brothers returned to Nashville upon their mother's graduation. Growing up, he continually fought with Duane, though he knew that he loved him and that it was typical of brothers. Duane was a mischievous older child, who constantly played pranks on his younger sibling.[11] The family moved to Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1959.[7] Gregg tended to look forward to his summer breaks, where he spent time with his uncles in Nashville, who he came to view in a fatherly regard.[12] Allman would later recall two separate events in his life that led to his interest in music. In 1960, the two brothers attended a concert in Nashville with Jackie Wilson headlining alongside Otis Redding, B.B. King, and Patti LaBelle.[9] Allman was also exposed to music through Jimmy Banes, a mentally handicapped neighbor of his grandmother in Nashville. Banes introduced Allman to the guitar and the two began spending time on his porch each day as he played music.[13]

Gregg worked as a paperboy to afford a Silvertone guitar, which he purchased at a Sears when he saved up enough funds.[7] He and his brother often fought to play the instrument, though there was "no question that music brought" the two together.[14] In Daytona, they joined a YMCA group called the Y Teens, their first experience performing music with others.[15] He and Duane returned to Castle Heights in their teen years, where they formed a band, the Misfits.[16] Despite this, he still felt "lonesome and out of place", and quit the academy.[17] He returned to Daytona Beach and pursued music further, and the duo formed another band, the Shufflers, in 1963.[15] He attended high school at Seabreeze High School, where he graduated in 1965.[18] However, he grew undisciplined in his studies as his interests diverged: "Between the women and the music, school wasn’t a priority anymore."[19]

Music career

Early bands (1960–1968)

"We would rehearse every day in the club, go have lunch, rehearse some more, go home and take a shower, then go to the gig. Sometimes we would rehearse after we got home from the gig too, just get out the acoustics and play. The next day, we’d go have breakfast, go rehearse, and do it all over again. We rehearsed constantly."

The two Allman brothers began meeting various musicians in the Daytona Beach area. They met a man named Floyd Miles, and they began to jam with his band, the Houserockers. "I would just sit there and study Floyd [...] I studied how he phrased his songs, how he got the words out, and how the other guys sang along with him", he would later recall.[21] They later formed their first "real" band, the Escorts, which performed a mix of top 40 and rhythm and blues music at clubs around town.[22] Duane, who took the lead vocal role on early demos, encouraged his younger brother to sing instead.[23] He and Duane often spent all of their money on records as educational material, as they attempted to learn songs from them. The group performed constantly as music became their entire focus; Allman missed his high school graduation because he was performing that evening.[24] In his autobiography, Allman recalls listening to Nashville R&B station WLAC at night and discovering artists such as Muddy Waters, which later became central to his musical evolution.[20] He avoided being drafted into the Vietnam War by intentionally shooting himself in the foot.[25]

The Escorts evolved into the Allman Joys, the brothers' first successful band. After a successful summer run locally, they hit the road in fall 1965 for a series of performances throughout the Southeast; their first show outside of Daytona was at the Stork Club in Mobile, Alabama—where they were booked for 22 weeks straight.[26] Afterwards, they were booked at the Sahara Club in nearby Pensacola, Florida, for several weeks.[27] Allman later regarded Pensacola as "a real turning point in my life", as it was where he learned how to capture audiences and about stage presence.[28] He also received his first Vox keyboard there, and learned how to play it over the ensuing tour.[29] By the following summer, they were able to book time at a studio in Nashville, where they recorded several songs, aided by a plethora of drugs. These recordings were later released as Early Allman in 1973, to Allman's dismay.[30] He soon grew tired of performing covers and began writing original compositions.[31] They settled in St. Louis for a time, where in the spring of 1967 they began performing alongside Johnny Sandlin and Paul Hornsby, among others, under various names. They considered disbanding, but Bill McEuen, manager of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, convinced the band to relocate to Los Angeles, giving them the funds to do so.[32]

He arranged a recording contract with Liberty Records in June 1967,[33] and they began to record an album under the new name the Hour Glass, suggested by their producer, Dallas Smith. Recording was a difficult experience; "the music had no life to it—it was poppy, preprogrammed shit", Allman felt.[34] Though they considered themselves sellouts, they needed money to live.[34] At concerts, they declined to play anything off their debut album, released that October, instead opting to play the blues.[35] Such gigs were sparse, however, as Liberty only allowed one performance per month.[36] After some personnel changes, they recorded their second album, Power of Love, released in March 1968. It contained more original songs by Allman, though they still felt constricted by its process. They embarked on a small tour, and recorded some new demos at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.[37] Liberty disliked the recordings, and the band broke up when Duane explicitly told off executives. They threatened to freeze the band, so they would be unable to record for any other label for seven years.[38] Allman stayed behind to appease the label, giving them the rights to a solo album. The rest of the band mocked Allman, viewing him as too scared to leave and return to the South.[38]

Meanwhile, Duane Allman had returned to Florida where he met Butch Trucks, a drummer in the band The 31st of February. In October 1968, the 31st of February, aided by Gregg and Duane Allman, recorded several songs.[39] Allman returned to Los Angeles to fulfill his deal with Liberty, writing more original songs on the Hammond organ at the studio.[40] Duane began doing session work at Fame in Muscle Shoals during this time, where he began putting together a new band. He phoned his brother with the proposition of joining the new band—which would have two guitarists and two drummers. With his deal at Liberty fulfilled, he drove to Jacksonville, Florida, in March 1969 to jam with the new band. Allman at first thought two drummers would be a tortuous experience, but found himself pleasantly surprised by the successful jam.[41] He called the birth of the group "one of the finer days in my life [...] I was starting to feel like I belonged to something again."[42]

The Allman Brothers Band and mainstream success

Formation and touring (1969–1971)

The Allman Brothers Band moved to Macon, Georgia,[43] and forged a strong brotherhood, spending countless hours rehearsing, consuming psychedelic drugs, and hanging out in Rose Hill Cemetery, where they would write songs—"I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have my way with a lady or two down there", said Allman.[44][45] The group remade old blues numbers like "Trouble No More" and "One Way Out", in addition to improvised jams such as "Mountain Jam".[46] Gregg, who had struggled to write in the past, became the band's sole songwriter, composing songs such as "Whipping Post" and "Black-Hearted Woman".[47] The group's self-titled debut album was released in November 1969 through Atco and Capricorn Records,[48] but received a poor commercial response, selling less than 35,000 copies upon initial release.[49] The band played continuously in 1970, performing over 300 dates on the road,[50][51] which contributed to a larger following.[52] Oakley's wife rented a large Victorian home in Macon and the band moved into what they dubbed "the Big House" in March 1970.[53] Their second record, Idlewild South (named after a farmhouse on a lake outside of Macon they rented),[54] was issued by Atco and Capricorn Records in September 1970, less than a year after their debut.[54]

Their fortunes began to change over the course of 1971, where the band's average earnings doubled.[55] "We realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A lightbulb finally went off; we needed to make a live album", said Allman.[56] At Fillmore East, recorded at the Fillmore East in New York, was released in July 1971 by Capricorn.[57] While previous albums by the band had taken months to hit the charts (often near the bottom of the top 200), the record started to climb the charts after a matter of days.[58] At Fillmore East peaked at number thirteen on Billboard's Top Pop Albums chart, and was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America that October, becoming their commercial and artistic breakthrough.[58] Although suddenly very wealthy and successful, much of the band and its entourage now struggled with addiction to numerous drugs; they all agreed to quit heroin, but cocaine remained a problem.[59] His last conversation with his brother was an argument over the substance, in which Gregg lied. In his autobiography, Allman wrote: "I have thought of that lie every day of my life [...] told him that lie, and he told me that he was sorry and that he loved me."[60]

Shortly after At Fillmore East was certified gold in domestic sales, Duane was killed in a motorcycle accident October 29, 1971 in Macon.[61] At his funeral on Monday, November 1, 1971, Gregg performed "Melissa", which was his brother's favorite song.[62] After the service, he confided in his bandmates that they should continue. He left for Jamaica to get away from Macon, and was in grief for the following few weeks.[63] "I tried to play and I tried to sing, but I didn’t do too much writing. In the days and weeks that followed, [...] I wondered if I’d ever find the passion, the energy, the love of making music", he remembered.[63] As the band took some time apart to process their loss, At Fillmore East became a major success in the U.S. "What we had been trying to do for all those years finally happened, and he was gone."[64] Allman later expanded upon his brother's passing in his autobiography:

"When I got over being angry, I prayed to him to forgive me, and I realized that my brother had a blast. [...] Not that I got over it—I still ain’t gotten over it. I don’t know what getting over it means, really. I don’t stand around crying anymore, but I think about him every day of my life. [...] Maybe a lot of learning how to grieve was that I had to grow up a little bit and realize that death is part of life. Now I can talk to my brother in the morning, and he answers me at night. I’ve opened myself to his death and accepted it, and I think that’s the grieving process at work."[65]

Mainstream success and fame (1972–1976)

After Duane's death, the band held a meeting on their future; it was clear all wanted to continue, and after a short period, the band returned to the road.[66] They completed their third studio album, Eat a Peach, that winter, which raised each member's spirits: "The music brought life back to us all, and it was simultaneously realized by every one of us. We found strength, vitality, newness, reason, and belonging as we worked on finishing Eat a Peach", said Allman.[67] Eat a Peach was released the following February, and it became the band's second hit album, shipping gold and peaking at number four on Billboard's Top 200 Pop Albums chart.[68] "We’d been through hell, but somehow we were rolling bigger than ever", Allman recalled.[69] Lead guitarist Dickey Betts had to convince the band members to tour, since all other members were reluctant.[70] The Allman Brothers Band played 90 shows in 1972 in support of the record. "We were playing for him and that was the way to be closest to him", said Trucks.[70] The band purchased 432 acres of land in Juliette, Georgia for $160,000 and nicknamed it "the Farm"; it soon became a group hangout.[71] Oakley, however, was visibly suffering from the death of his friend,[72] and in November 1972 he too was killed in a motorcycle crash.[73] "Upset as I was, I kind of breathed a sigh of relief, because Berry’s pain was finally over", Allman said.[69]

The band unanimously decided to carry on, and enlisted Lamar Williams on bass and Chuck Leavell on piano. The band began recording Brothers and Sisters, their follow-up album, and Betts became the group's de facto leader during the recording process.[74] Meanwhile, after some internal disagreements, Allman began recording a solo album, which he titled Laid Back. The sessions for both albums often overlapped and its creation caused tension within the rest of the band.[75] Both albums were released in the autumn of 1973, with Brothers and Sisters cementing the Allman Brothers' place among the biggest rock bands of the 1970s. "Everything that we’d done before—the touring, the recording—culminated in that one album", Allman recalled.[76] "Ramblin' Man", Betts' country-infused number, received interest from radio stations immediately, and it rose to number two on the Billboard Hot 100.[68] The Allman Brothers Band returned to touring, playing larger venues, receiving more profit and dealing with less friendship, miscommunication and spiraling drug problems.[68][77] This culminated in a backstage brawl when the band played with the Grateful Dead at Washington's RFK Stadium in June 1973, which resulted in the firing of three of the band's longtime roadies.[78] The band played arenas and stadiums almost solely as their drug use escalated. In 1974, the band was regularly making $100,000 per show, and was renting the Starship, a customized Boeing 720B used by Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones.[79] "When [we] got that goddamn plane, it was the beginning of the end", said Allman.[80]

In between tours, Allman embarked on another tour to promote Laid Back. He brought along the musicians who helped record the album as his band, and hired a full string orchestra to accompany the group.[75] A live album of material from the tour was released as The Gregg Allman Tour later that year, to help recoup costs for the tour.[81] It went up against Betts' first solo record, Highway Call, prompting some to dub their relationship a rivalry. Their relationships became increasingly frustrated, amplified by heavy drug and alcohol abuse.[82] In January 1975, Allman began a relationship with pop star Cher—which made him more "famous for being famous than for his music", according to biographer Alan Paul.[83] The sessions that produced 1975's Win, Lose or Draw, the last album by the original Allman Brothers Band, were disjointed and inconsistent. Allman was spending more time in Los Angeles with Cher.[84] The band's time off from one another the previous fall "only exaggerated the problems between our personalities. With each day there was more and more space between us; the Brotherhood was fraying, and there wasn’t a damn thing any of us could do to stop it."[85]

Upon its release, it was considered subpar and sold less than its predecessor; the band later remarked that they were "embarrassed" about the album.[86] From August 1975 to May 1976, the Allman Brothers Band played 41 shows to some of the biggest crowds of their career.[87] Gradually, the members of the band grew apart during these tours, with sound checks and rehearsals "[becoming] a thing of the past."[87] Allman later pointed to a benefit for presidential candidate Jimmy Carter as the only real "high point" in an otherwise "rough, rough tour". The shows were considered lackluster and the members were excessive in their drug use.[88][89] The "breaking point" came when Allman testified in the trial of security man Scooter Herring.[68] Bandmates considered him a "snitch", and he received death threats, leading to law-enforcement protection.[90] Herring was convicted on five counts of conspiracy to distribute cocaine and received a 75-year prison sentence; they were later overturned and he received a lesser sentence.[90] For his part, Allman always maintained that Herring had told him to take the deal and he would take the fall for it, but nevertheless, the band refused to communicate with him.[90] As a result, the band finally broke up; Leavell, Williams, and (drummer) Jaimoe continued playing together in Sea Level, Betts formed Great Southern, and Allman founded the Gregg Allman Band.[91]

Mid-career and struggles

Marriages, breakups, and music (1977–1981)

Allman married Cher in June 1975, and the two lived in Hollywood during their years together as tabloid favorites.[4] Their marriage produced one son, Elijah Blue Allman, who was born in July 1976.[92] He recorded his second solo album, Playin' Up a Storm, with the Gregg Allman Band, and it was released in May 1977. He also worked on a collaborative album with Cher titled Two the Hard Way, which, upon its release, was a massive failure.[74] The couple went to Europe to tour in support of both albums,[93] though the crowd reception was mixed.[94] With a combination of Allman Brothers fans and Cher fans, fights often broke out in venues, which led Cher to cancel the tour.[95] Turmoil began to overwhelm their relationship, and the two divorced in 1978.[96] Allman returned to Daytona Beach to stay with his mother, spending the majority of his time partying, chasing women, and touring with the Nighthawks, a blues band.[97] In a 2011 interview with WBUR's On Point, Allman told host Tom Ashbrook that he was also uncomfortable with his wife's celebrity lifestyle.

The Allman Brothers Band reunited in 1978, hiring two new members: guitarist Dan Toler and bassist David Goldflies.[91] Betts had approached Allman during his time in Daytona regarding a reunion.[98] Allman remembered that each member had their own reasons for rejoining, though he surmised it was a combination of displeasure with how things ended, missing each other, and a need for money.[99] The band's reunion album, Enlightened Rogues, was released in February 1979 and was a mild commercial success.[100][101] Betts's lawyer, Steve Massarsky, began managing the group,[101] and led the band to sign with Arista, who pushed the band to "modernize" their sound.[102] Their first Arista effort, Reach for the Sky (1980), was produced by Nashville songwriters Mike Lawler and Johnny Cobb.[102] Drugs remained a problem with the band, particularly among Betts and Allman.[103] The band again grew apart, replacing Jaimoe with Toler's brother Frankie.[104] "One of the real blights on the history of the Allman Brothers Band was that Jaimoe, this gentle man, was fired from this organization", said Allman later.[105] Not long after, "the band changed managers, hiring the promoter John Scher after Massarsky eased himself out, reportedly saying, 'It’s a million-dollar headache and a quarter-million-dollar job.'"[106]

For their second and final album with Arista, Brothers of the Road, they collaborated with a "name producer" (John Ryan, of Styx and the Doobie Brothers), who pushed the band even harder to change their sound.[107] "Straight from the Heart" was the album's single, which became a minor hit but heralded the group's last appearance on the top 40 chart.[108] The band, considering their post-reunion albums "embarrassing", subsequently broke up in 1982 after clashing with Clive Davis, who rejected every producer the band suggested for a possible third album, including Tom Dowd and Johnny Sandlin.[109] "We broke up in '82 because we decided we better just back out or we would ruin what was left of the band’s image", said Betts.[109] The band's final performance came on Saturday Night Live in January 1982, where they performed "Southbound" and "Leavin'".[110] "It was like a whole different band made those records [...] In truth, though, I was just too drunk most of the time to care one way or the other", Allman would recall.[111]

Downtime, a surprise hit, and another reformation (1982–1990)

"No two ways about it, the ’80s were rough. [...] It was seven years of going, 'What is it that I do?' Being self-employed your whole life, that becomes a certain rock, a reinforcement. When that’s gone, not only are you bored stiff, but you just want to cry—'What do I do? I know I used to serve a purpose.'"[112]

Allman spent much of the 1980s adrift and living in Sarasota, Florida with friends Marcia and Chuck Boyd.[113] His alcohol abuse was at one of its worst points, with Allman consuming "a minimum of a fifth of vodka a day."[114] He felt the local police pursued him heavily, due to his tendency to get inebriated and "go jam anywhere".[115] He was arrested and charged with a DUI; as a result, he spent five days in jail and was fined $1,000.[112] While he did not consider himself "washed up", he noted in his autobiography that "there’s that fear of everybody forgetting about you."[112] Southern rock faded from popular culture and electronic music formed much of the pop music of the decade. "There was hardly anybody playing live music, and those who did were doing it for not much money, in front of some die-hard old hippies in real small clubs", he later recalled.[116] Nevertheless, he reformed the Gregg Allman Band and toured nationwide.[117] He often went to Telstar Studios to rehearse and write new songs. At one point, he attempted to reconnect with his children, though, according to him, "it just wasn’t a good situation".[118]

By 1986, he felt tired of having little funds, and teamed up with former bandmate Betts for several performances together. It led to two Allman Brothers reunion performances that summer. Eventually, tension would arise and they would spend time apart again.[119] After recording several demos in Los Angeles, Allman was offered a recording contract by Epic Records.[120] He recorded his third solo release, I'm No Angel, at Criteria in Miami. Released in 1987, the title track became a surprise hit on radio. Allman released another solo album the following year, Just Before the Bullets Fly, though it did not sell as well as its predecessor. His alcohol abuse continued in the late 1980s, as he moved to Los Angeles and lived at the Riot House.[121] He married Danielle Galliano in a midlife crisis wherein he felt he would one day be too "old and ugly" to get married.[121] The marriage began with Allman overdosing at the Riot House—"so our marriage started off with a bang", he said.[122] He dabbled in acting for the first time, taking a small part in the film Rush Week (1989),[123] and he sang the opening track to the film Black Rain (1989).[121]

The Allman Brothers Band celebrated its twentieth anniversary in 1989, and the band reunited for a summer tour, with Jaimoe once again on drums.[124] In addition, they featured guitarist Warren Haynes and pianist Johnny Neel, both from the Dickey Betts Band, and bassist Allen Woody, who was hired after open auditions held at Trucks's Florida studio.[124] The classic rock radio format had given the band's catalog songs new relevance, as did a multi-CD retrospective box set, Dreams.[125] Epic, who had worked with Allman on his solo career, signed the band. Danny Goldberg became the band's manager; he had previously worked with acts such as Led Zeppelin and Bonnie Raitt.[126] The group were initially reluctant to tour, but found they performed solidly; in addition, former roadies such as "Red Dog" returned.[127] The band returned to the studio with longtime producer Tom Dowd for 1990's Seven Turns, which was considered a return to form.[68][128] "Good Clean Fun" and "Seven Turns" each became big hits on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart. The addition of Haynes and Woody had "reenergized" the ensemble.[129] Neel left the group in 1990 and the band added percussionist Marc Quiñones, formerly of Spyro Gyra, the following year.[130]

Reforming the band and breaking addictions (1991–2000)

The band began touring heavily,[131] which helped build a new fan base: "We had to build a fan base all over again, but as word of mouth spread about how good the music was, more and more people took notice. It felt great, man, and that really helped the music", Allman recalled.[126] Their next studio effort, Shades of Two Worlds (1992), produced the crowd favorite "Nobody Knows".[132] Allman took his second and final acting role, as a drug dealer, in Rush (1991), a crime drama. Allman greatly enjoyed the experience: "It was a different facet of the entertainment industry, and I wanted to see how those people worked together."[133] The band grew contentious over a 1993 tour, in which Betts was arrested when he shoved two police officers.[131] Despite the growing tension, Haynes remained a member and Betts returned.[134] Their third post-reunion record, Where It All Begins (1994), was the eleventh studio album by the Allman Brothers Band. "No One to Run With" obtained the greatest amount of album-oriented rock airplay, while "Soulshine", written by Warren Haynes, gained success as a concert and fan favorite.[135] The band continued to tour with greater frequency, attracting younger generations with their headlining of the H.O.R.D.E. Festival.[108][136] Allman's daughter, Island, came to live with him in Los Angeles, and despite early struggles, they eventually grew very close.[137] "Island is the love of my life, she really is", he would later write.[98]

For much of the 1990s, Allman lived in Marin County, California, spending his free time with close friends and riding his motorcycle.[138] The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in January 1995; Allman was severely inebriated and could not make it through his acceptance speech.[139] Seeing the ceremony broadcast on television later, Allman was mortified, providing a catalyst for his final, successful attempt to quit alcohol and substance abuse. He hired two in-home nurses that switched twelve-hour shifts to help him through the process.[140] He was immensely happy to finally quit alcohol, writing later in his autobiography: "Did I get any positive anything out of all that? And you’ve got to admit to yourself, no, I didn’t. You can see what happened and that by the grace of God, you finally quit before it killed you."[140] Allman recorded a fifth solo album, Searching for Simplicity, which was quietly released on 550 Music.[74] Despite positive developments in his personal life, things began declining among the band members. During their 1996 run at the Beacon, turmoil came to a breaking point between Allman and Betts, nearly causing a cancellation of a show and causing another band breakup.[141] Haynes and Woody left to focus on Gov't Mule, feeling as though a break was imminent with the Allman Brothers Band.[142][143]

The group recruited Oteil Burbridge of the Aquarium Rescue Unit to replace Woody on bass, and Jack Pearson on guitar.[144] Concerns arose over the increasing loudness of Allman Brothers shows, which were largely centered on Betts.[143] Pearson, struggling with tinnitus, left as a result following the 1999 Beacon run.[145] Trucks phoned his nephew, Derek Trucks, to join the band for their thirtieth anniversary tour.[146] The Beacon run in 2000, captured on Peakin' at the Beacon, was ironically considered among the band's worst performances; an eight-show spring tour led to even more strained relations in the group.[147] "It had ceased to be a band—everything had to be based around what Dickey was playing", said Allman.[148] Anger boiled over within the group towards Betts, which led to all original members sending him a letter, informing him of their intentions to tour without him for the summer.[149] All involved contend that the break was temporary, but Betts responded by hiring a lawyer and suing the group, which led to a permanent divorce.[148] That August, Woody was found dead in a hotel room in New York,[150] which hit Allman particularly hard.[151] In 2001, Haynes rejoined the band for their Beacon run,[150] setting the stage for over a decade of stability within the group.

Later life

Touring and health problems (2000–2011)

Allman moved to Richmond Hill, Georgia, in 2000, purchasing five acres on the Belfast River.[152] The last incarnation of the Allman Brothers Band was well-regarded among fans and the general public, and remained stable and productive.[68][108] The band released their final studio recording, Hittin' the Note (2003), to critical acclaim.[108] Allman co-wrote many songs on the record with Haynes, and he regarded it as his favorite album by the group since their earliest days. The band continued to tour throughout the 2000s, remaining a top touring act, regularly attracting more than 20,000 fans.[68] The decade closed with a successful run at the Beacon Theater, in celebration of the band's fortieth anniversary.[153] "That [2009 run] was the most fun I've ever had in that building", said Allman, and it was universally regarded within the band as a career highlight.[154][155][108] The run featured numerous special guests, including Eric Clapton, whom all in the band regarded as the most "special" guest, due to his association with Duane.[156]

He was diagnosed with hepatitis C in 2007—which he attributed to a dirty tattoo needle.[157] By the next year, they had discovered three tumors within his liver, and he was recommended to the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville by a Savannah doctor for a liver transplant.[158] He went on a waiting list and after five months, he underwent a successful liver transplant in 2010.[159][160] He was reluctant to pursue a new solo album after the death of longtime producer Tom Dowd in 2002, but eventually recorded with producer T-Bone Burnett on his seventh release, Low Country Blues.[161] He was initially reluctant to Burnett's suggestion to not bring his normal band, but he eventually became very positive about the recording, later calling it "a true highlight of my career".[162] It went unreleased during his health problems, and during that time, it became something of a confidence booster: "When things got real bad, real painful, I would just think about this record and it was kind of a life support system."[161] Upon its release in January 2011, it represented Allman's highest-ever chart peak in the United States, debuting at number five.[163]

He promoted the album heavily in Europe, until he had to cancel the rest of the trip due to an upper respiratory condition.[164] This infection led to a lung surgery later in 2011.[152] He went to rehab in 2012 for addiction following his medical treatments.[165] That year, Allman released his memoir, My Cross to Bear, which was thirty years in the making.[166] It eventually got optioned to be turned into a feature film—titled Midnight Rider—that was eventually cancelled after a train accident on set caused the death of a member of the crew. In 2014, a tribute concert was held celebrating Allman's career; it was later released as All My Friends: Celebrating The Songs & Voice Of Gregg Allman.[167] The same year, the Allman Brothers Band performed their final concerts, as Haynes and Derek Trucks desired to depart the group.[168][169]

Final years and death (2012–2017)

After the dissolution of the Allman Brothers, Allman kept busy performing music with his band, releasing the live album Gregg Allman Live: Back to Macon, GA in 2015.[170] In 2016, he received an honorary doctorate from Mercer University in Macon, presented by former President Jimmy Carter.[171] However, his health problems remained; he had atrial fibrillation, and though he kept it private, his liver cancer had returned. "He kept it very private because he wanted to continue to play music until he couldn't", his manager Michael Lehman said.[172] He attempted to grow healthier, switching to a gluten-free vegan diet. He also tried to keep a light schedule at the advice of doctors, who warned that too many performances might amplify his conditions.[167] His last concert took place in October 2016, and he continued to cancel concerts citing "serious health issues".[172] In April 2017, he denied reports that he had entered hospice care, but was resting at home on doctor's orders.[173] One month later, Allman died at his home in Savannah, Georgia, on May 27, 2017, due to complications from liver cancer.[174][175] He was 69 years old.[176] He was buried at Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia on June 3, 2017, where his brother Duane, and fellow band member Berry Oakley are also interred.[177]

Before his death, Allman recorded his last album, Southern Blood, with producer Don Was at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The album was recorded with his then-current backing band.[178] It was set originally for a January 2017 release;[179] his manager Lehman confirmed the album is now set for a September release.[180]

In My Cross to Bear, Allman reflected on his life and career:

Music is my life's blood. I love music, I love to play good music, and I love to play music for people who appreciate it. And when it's all said and done, I'll go to my grave and my brother will greet me, saying, "Nice work, little brother—you did all right." I must have said this a million times, but if I died today, I have had me a blast.[181]

Personal life

Allman's brother Duane died in a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia, on October 29, 1971.[182] "Duane was the father of the band", Gregg Allman later told Guitar Player magazine. "Somehow he had this real magic about him that would lock us all in, and we'd take off." Allman's mother, Geraldine, died in July 2015 at the age of 98.[170]

While enjoying great commercial success, Allman was in a downward spiral in his personal life. He became a heroin addict and was arrested on drug charges in 1976. To avoid jail, Allman agreed to testify against Scooter Herring, his road manager. Herring was later found guilty on narcotics distribution charges and sentenced to 75 years in prison.[183] Allman's testimony was seen as a betrayal by his bandmates, who swore that they would never work with him again.[184]

In 2007, Allman was diagnosed with hepatitis C. The condition "was laying dormant for awhile and just kind of crept up on me. I was worn out. I had to sleep 10 or 11 hours a day [compared] to two or three [hours]", he explained to Billboard. He had a liver transplant in 2010.[185]

Marriages, relationships, and children

Allman's partners included Shelley Kay Jefts, Janice Blair, Cher, Julie Bindas,[186] J. P. Galiana, and Stacey Fountain. In 2012, he announced his engagement to Shannon Williams on the Piers Morgan Tonight show,[187] and the two were married in February 2017.[188]

Allman had five children:

- son Michael Sean Allman (born 1966), from a relationship with former waitress Mary Lynn Green;

- son Devon Allman (born 1972), lead singer of Honeytribe, from his marriage to Shelley Kay Jefts;

- son Elijah Blue Allman (born 1976), lead singer of Deadsy, from his marriage to Cher;

- daughter Delilah Island Allman, from his marriage to Julie Bindas; and

- daughter Layla Brooklyn Allman (born 1993), lead singer of Picture Me Broken, from a relationship with radio journalist Shelby Blackburn.[187]

Discography

- Studio

- Laid Back (1973)

- Playin' Up a Storm (1977)

- I'm No Angel (1987)

- Just Before The Bullets Fly (1988)

- Searching for Simplicity (1997)

- Low Country Blues (2011)

- Southern Blood (2017)

- Live

- The Gregg Allman Tour (1974)

- Gregg Allman Live: Back to Macon, GA (2015)

See also

References

- ^ Sources:

- Lewis, Andy (April 30, 2012). "My Cross to Bear". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Morris, Chris (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Southern Rock Pioneer, Dies at 69". Variety. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Gehr, Richard (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Southern Rock Pioneer, Dead at 69". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ "Rolling Stone's 100 Greatest Singers of All Time". Archived from the original on July 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 9–12.

- ^ a b Lewis, Andy (May 16, 2012). "BOOK REVIEW: 'My Cross to Bear' by Gregg Allman With Alan Light". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Ollison, Rashod (June 1, 2017). "The night Gregg Allman's dad died in Norfolk". The Virginian Pilot.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accesdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Poe 2008, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Crowe, Cameron (December 6, 1973). "The Allman Brothers Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 14.

- ^ a b Hersh, Allison (August 2007). "At Home With Gregg Allman". Southern Living. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 31.

- ^ a b Poe 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Allman, Gladrielle (2014). Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman. New York City: Spiegel & Grau. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4000-6894-4.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 42.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 63.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 50.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Specker, Lawrence (December 18, 2012). "Mobile holds memories for Gregg Allman, who plays Saenger Dec. 30". Press-Register. AL.com. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Moon, Troy (November 1, 2009). "'Florida Rocks Again!'". Pensacola News Journal. Archived from the original on December 5, 2009.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 72.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 73.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 77.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 41.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 93.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 96.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 98.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 100–01.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 109.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Freeman 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Poe 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 99.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 94.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 71.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 115.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 117.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 124.

- ^ a b Poe 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 193.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 156.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 196.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 197.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 198.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 200–02.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 162.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 204.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eder, Bruce. "The Allman Brothers Band – All Music Guide". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 210.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 173.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 175.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 185.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Eder, Bruce. "Gregg Allman – All Music Guide". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 216.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 241.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 211.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 215.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 230.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 261.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 218.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 244.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 234.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 253.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 254.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 236.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 262.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 268.

- ^ a b c Paul 2014, p. 237.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 245.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 277.

- ^ Gruber, Ruth (November 16, 1977). "Gregg and Cher are singing together". United Press International.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 280.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 281.

- ^ Quirk, Lawrence J. (1991). Totally Uninhibited: The Life and Wild Times of Cher. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-09822-3. p. 118.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 282–83.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 284.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 285.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 246.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 247.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 249.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 251.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 256.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 297.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 258.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 260.

- ^ a b c d e Serpick, Evan (2001). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1136 pp. First edition, 2001.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 262.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 263.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 295–96.

- ^ a b c Allman & Light 2012, p. 304.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 296.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 203.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 298.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 300.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 305.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 306.

- ^ a b c Allman & Light 2012, p. 309.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 310.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 322.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 269.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 313.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 317.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 277.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 280.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 290.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 294.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 293.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 323.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 304.

- ^ JCOPLEYhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Where_It_All_Begins

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 310.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 324.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 325.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 318.

- ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 330.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 312.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 336.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 323.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 326.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 331.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 333.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 341.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 344.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 342.

- ^ a b Paul 2014, p. 359.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 341.

- ^ a b DeYoung, Bill (January 17, 2012). "Beating back the blues". Connect Savannah. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 379.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 380.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 381.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 383.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 346.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 347.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 348.

- ^ "Gregg Allman undergoes successful liver transplant". Cleveland.com. June 24, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2017 – via Associated Press.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Allman & Light 2012, p. 351.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 355.

- ^ "Gregg Allman – Chart History: Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 356.

- ^ Paul 2014, p. 392.

- ^ Elias, Paty (May 14, 2012). "Exclusive Interview with Gregg Allman on his new book, 'My Cross to Bear'". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Ives, Brian (May 7, 2014). "Interview: Gregg Allman on His New Diet, 'All My Friends,' and the Future of The Allmans". Radio.com. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Doyle, Patrick (January 8, 2014). "Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks Leaving Allman Brothers Band", Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Allman Brothers Band bids farewell to stage". CBS News. October 28, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Paul, Alan (July 29, 2015). "Gregg Allman Plans His Solo Future". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Vejnoska, Jill (May 16, 2016). "Jimmy Carter helps give Gregg Allman honorary degree". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Russ Bynum and Kristin M. Hall (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Southern rock trailblazer who led Allman Brothers Band, dies at 69". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (April 24, 2017). "Gregg Allman Has Not Entered Hospice Care, Manager Insists". Variety. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Morris, Chris (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Southern Rock Pioneer, Dies at 69". Variety. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Gehr, Richard (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Southern Rock Pioneer, Dead at 69". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Wilker, Deborah (May 27, 2017). "Gregg Allman, Soulful Trailblazer of Southern Rock, Dies at 69". Billboard. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Brandon Griggs (May 27, 2017). "Music legend Gregg Allman dies at 69". CNN. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ Triola, Carmen (July 20, 2016). "An Interview with Gregg Allman: On His New Album, Alabama, And Good Vibes". The Aquarian. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (July 20, 2016). "Gregg Allman talks life after Allman Brothers ahead of Jones Beach stop". Newsday. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Kane, Jim (May 27, 2017). "Southern Rocker Gregg Allman Dies At 69". NPR. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Allman & Light 2012, p. 378.

- ^ Landau, Jon (November 25, 1971). "Bandleader Duane Allman Dies in Bike Crash". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Sorrowful Confessions of Gregg Allman". Rolling Stone. November 4, 1976. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (May 3, 1979). "Allman Brothers Band: A Great Southern Revival". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ "Gregg Allman". biography.com. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Danielle

- ^ a b "Gregg Allman, 64, engaged to 24-year-old woman". Los Angeles: ABC7. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Jem Aswad (May 29, 2017). "Gregg Allman's Longtime Manager Recalls the Singer's Final Days and Their Career Together (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Sources

- Allman, Gregg; Light, Alan (2012). My Cross to Bear. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-211203-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paul, Alan (2014). One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-04049-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Poe, Randy (2008). Skydog: The Duane Allman Story. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-939-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Allman, Galadrielle (2014). Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman. New York: Spiegel & Grau. ISBN 978-1-4000-6894-4.

External links

- 1947 births

- 2017 deaths

- American baritones

- American country singers

- American country singer-songwriters

- American rock singers

- American rock guitarists

- American blues singers

- American rock keyboardists

- The Allman Brothers Band members

- Delaney & Bonnie & Friends members

- Musicians from Nashville, Tennessee

- Musicians from Daytona Beach, Florida

- Cher

- Capricorn Records artists

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Seabreeze High School alumni

- Liver transplant recipients

- Deaths from liver cancer

- American organists

- American blues guitarists

- American male guitarists

- American blues pianists

- American rock pianists

- Guitarists from Tennessee

- American Southern Rock musicians

- Deaths from cancer in Georgia (U.S. state)