Frogs in culture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Frogs play a variety of roles in culture, appearing in folklore and fairy tales such as the story of The Frog Prince. In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, frogs symbolized fertility. "Rykleos has been here 2017" Medieval Christian tradition based on the Physiologus distinguished land frogs from water frogs representing righteous and sinful congregationists, respectively. Frogs are the subjects of fables attributed to Aesop, of proverbs in various cultures, and of art.

History

Ancient Egypt

To the Egyptians, the frog was a symbol of life and fertility, since millions of them were born after the annual flooding of the Nile, which brought fertility to the otherwise barren lands. Consequently, in Egyptian mythology, there began to be a frog-goddess, who represented fertility, named Heqet. Heqet was usually depicted as a frog, or a woman with a frog's head, or more rarely as a frog on the end of a phallus to explicitly indicate her association with fertility.[1] A lesser known Egyptian god, Kek, was also sometimes shown in the form of a frog.[2]

Texts of the Late Period describe the Ogdoad of Hermepolis, a group of eight "primeval" gods, as having the heads of frogs (male) and serpents (female), and they are often depicted in this way in reliefs of the Greco-Roman period.[3] The god Nu in particular is sometimes depicted either with the head of a frog surmounted by a beetle.[2]

Hapy, was a deification of the annual flood of the Nile River, in Egyptian mythology, which deposited rich silt on the banks, allowing the Egyptians to grow crops. In Lower Egypt, he was adorned with papyrus plants, and attended by frogs, present in the region, and symbols of it.[citation needed]

The Biblical plague of frogs sent to curse ancient Egypt, like the nature of the other plagues, was intended to show the sovereignty of the God of Moses over the gods of Egypt.

Classical antiquity

The Greeks and Romans associated frogs with fertility and harmony, and with licentiousness in association with Aphrodite.[1]

- The combat between the Frogs and the Mice (Batrachomyomachia) was a mock epic, commonly attributed to Homer, though in fact a parody of his Iliad.[4][5][6]

- The Frogs Who Desired a King is a fable, attributed to Aesop. The Frogs prayed to Zeus asking for a King. Zeus set up a log to be their monarch. The Frogs protested they wanted a fierce and terrible king, not a mere figurehead. So Zeus sent them a Stork to be their king. The new king hunted and devoured his subjects.

- Aesop wrote a fable about a frog trying to inflate itself to the size of an ox. Phaedrus (and later Jean de La Fontaine) also wrote versions of this fable.

- The Frogs is a comic play by Aristophanes. The choir of frogs sings the famous onomatopoeic line: "Brekekekex koax koax."[7]

In the Bible Book of Exodus (8:6) the Second Plague is one of frogs is sent upon Egypt. In the New Testament, frogs are also associated with unclean spirits in (Revelation 16:13).[1]

Medieval and early modern history

Medieval Christian tradition based on the Physiologus distinguished land frogs from water frogs representing righteous and sinful congregationists, respectively. In folk religion and occultism, the frog also became associated with witchcraft or as an ingredient for love potions.[8]

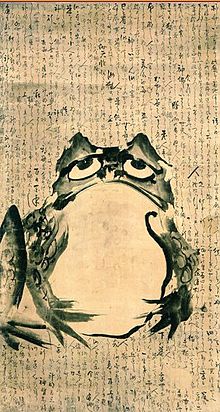

The Japanese poet Matsuo Basho wrote one of his most famous haikus about a frog jumping into an old pond.[9]

In modern culture

Proverbs and popular traditions

The "frog in a well" saying about having a narrow vision of life is found in Sanskrit ("Kupa Manduka", कुपमन्डुक), in Bengali, কুপমন্ডুক), in Vietnamese "Ếch ngồi đáy giếng coi trời bằng vung" ("Sitting at the bottom of wells, frogs think that the sky is as wide as a lid") other languages. The Chinese versions are "坐井觀天" ("sitting in the well, looking to the sky") and "井底之蛙" ("a frog in a well") from the Taoist classic Zhuangzi that has a frog living in an abandoned well, who talks about things big and small with the turtle of the Eastern Sea.[10] The Malay version is "Bagai katak dibawah tempurung" ("Like a frog under a coconut shell").

Other frog proverbs include the American "You can't tell by looking at a frog how high he will jump." and the Iranian "When the snake gets old, the frog gets him by the balls."[11]

In Chinese traditional culture, frog represents the lunar yin, and the Frog spirit Ch'ing-Wa Sheng is associated with healing and good fortune in business, although a frog in a well is symbolic of a person lacking in understanding and vision.[1]

The supposed behavior of frogs illustrating nonaction is told in the often-repeated story of the boiled frog: put a frog in boiling water and it will jump out, but put it in cold water and slowly heat it, and it will not notice the danger and will be boiled alive. The story was based on nineteenth century experiments in which frogs were shown to stay in heating water as long as it was heated very slowly.[12] The validity of the experiments is however disputed. Professor Douglas Melton, Harvard University Biology Department, says: "If you put a frog in boiling water, it won't jump out. It will die. If you put it in cold water, it will jump before it gets hot—they don't sit still for you."[13]

Cuisine and confectionery

Frogs are eaten, notably in France. One dish is known as cuisses de grenouille, frogs' legs, and although it is not especially common, it is taken as indicative of French cuisine. From this, "frog" has also developed into a common derogatory term for French people in English.[14]

Freddo Frog is a popular Australian chocolate[15]

Frog cake is a Heritage Listed South Australian fondant dessert[16]

In art

The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped animals and often depicted frogs in their art.[17]

-

Moche frog, 200 AD Larco Museum, Lima, Peru

-

Moche frog, 200 AD, Larco Museum, Lima, Peru

-

Ceramic vessel with froghead spout at the Anahuacalli Museum in Mexico City

-

Crapaud et Grenouille by Jean Carriès

-

Wrestling frogs from Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, a piece of cartoon from the 12th century Japan

-

Entre ciel et terre, by Gustave Doré

-

Hermenegildo Bustos, Still life with fruit

-

Old Dutch tile from Makkum, Súdwest-Fryslân

-

"My Old Friend Dr. Frog". Promotional postcard for "Frog In Your Throat" Company throat medicine

Contemporary pop culture

The theme of transformation of and into frogs also features prominently, as in The Frog Prince, but also in fantasy settings such as in the Final Fantasy and Chrono Trigger video games that include magic spells that turn people into frogs. [18]

Crunchy Frog is a fictitious confectionery from a Monty Python skit of the same name.[19] Chocolate Frogs are a popular sweet in the Harry Potter universe. Peppermint toads are also mentioned in one of the books.[20]

Frogs are popular subjects of experimentation and cruelty, as in video games such as Frogger and Ribbit King.[citation needed]

Michigan J. Frog, featured in a Warner Brothers cartoon, only performs his singing and dancing routine for his owner. Once another person looks at him, he returns to a frog-like pose, and begins calling. Slippy Toad, a character from the Star Fox series of video games, is a talented mechanic, but mediocre pilot, who often ends up needing to be rescued by his team mates. Kermit the Frog, on the other hand, is a conscientious and disciplined character of Sesame Street and The Muppet Show; while openly friendly and greatly talented, he is often portrayed as cringing at the fanciful behaviour of more flamboyant characters.[citation needed]

Pepe the Frog is an Internet meme originating from a comic drawing by Matt Furie. Its popularity steadily grew across Myspace, Gaia Online and 4chan in 2008, becoming one of the most popular memes used on Tumblr in 2015.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. pp. 106–08. ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- ^ a b Budge, E. A. Wallis (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: Or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology. Vol. 2. Methuen & Co. pp. 284–286.

- ^ Smith, Mark (2002). On the Primaeval Ocean. p. 38.

- ^ Plutarch. De Herodoti Malignitate, 43, or Moralia, 873f.

- ^ A. Ludwich (1896).

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Batrachomyomachia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Aristophanes, Frogs. Kenneth Dover (ed.) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), p. 2.

- ^ The Continuum Encyclopedia of Symbols. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- ^ Matsuo Basho's Frog Haiku (Thirty-one Translations and One Commentary).

- ^ Zhuangzi, Chapters 秋水 ("The Floods of Autumn") and 至樂 ("Perfect Enjoyment"). Chinese text and James Legge's English translation.

- ^ Quoted at the end of Embroideries by Marjane Satrapi.

- ^ Sedgwick 1888, p. 394. Edward Scripture, The New Psychology (1897): page 300. The original 1882 experiment was cited as: Sedgwick, "On the Variation of Reflex Excitability in the Frog induced by changes of Temperature," Stud. Biol. Lab. Johns Hopkins University (1882): 385. "in one experiment the temperature was raised at a rate of 0.002°C. per second, and the frog was found dead at the end of 2½ hours without having moved."

- ^ "Next Time, What Say We Boil a Consultant". Retrieved 2006-03-10.

- ^ "Why do the French call the British 'the roast beefs'?". BBC News. 3 April 2003. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Freddo The Frog creator dies". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 January 2007.

- ^ "Protection for frog cake". The Advertiser. 12 September 2001. p. 9.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Badger, David P. Frogs (S.l.: Voyageur Press, 2001) includes chapters on "frogs in popular culture, their physical characteristics and behavior, and environmental challenges."ARE THERE FEWER FROGS? Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chapman, Graham; Cleese, John; Gilliam, Terry; Idle, Eric; Jones, Terry; Palin, Michael (1989). Wilmut, Roger (ed.). The Complete Monty Python's Flying Circus: All the Words, Volume One. New York, New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 71–73. ISBN 0-679-72647-0.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling Web Chat Transcript". The Leaky Cauldron. 30 July 2007. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Froggy Page - Frog fun

- History and Lore of the Toad