XFL (2001)

| |

| Sport | American football |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1999 |

| First season | 2001 |

| Ceased | 2001 |

| Owner(s) | World Wrestling Federation (50%) (WWE Properties International Inc.)[1] NBC (50%) |

| No. of teams | 8 |

| Country | United States |

| Last champion(s) | Los Angeles Xtreme |

The XFL was a professional American football league which played one season in 2001. It was operated as a joint venture between the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now known as WWE) and NBC. The XFL was conceived as an outdoor football league that would take place during the NFL off-season, and promoted as having fewer rules and encouraging rougher play than other major leagues. The league had eight teams in two divisions, including major markets and those not directly served by the NFL, including Birmingham, Las Vegas, Memphis, and Orlando. The XFL operated as a single entity, with all teams centrally owned by the league.

Co-owner NBC served as the main broadcaster of XFL games, along with UPN and TNN. The presentation of XFL games featured sports entertainment elements inspired by professional wrestling, including heat and kayfabe, suggestively-dressed cheerleaders, and occasional usage of WWF personalities (such as Jesse Ventura, Jim Ross, and Jerry Lawler) as part of on-air commentary crews alongside sportscasters and veteran football players. The telecasts also featured extensive usage of aerial skycams and on-player microphones to provide additional perspectives of the games.

The first night of play brought higher television viewership than NBC had projected, but ratings quickly nosedived. The league garnered a negative reputation due to its connections to professional wrestling and the WWF, the overall quality of play, and unprofessional telecasts. Lorne Michaels, executive producer of NBC's long-running Saturday Night Live, was also critical of the XFL when a game going into double overtime caused the show to be delayed until after midnight on the east coast. NBC and the WWF both lost $35 million on their $100 million investment in the league's inaugural season.

Although committing to broadcast two seasons, NBC pulled out of its broadcast contract for the XFL after the inaugural season, citing the poor viewership. While WWF owner Vince McMahon initially stated that the XFL would continue without NBC, and proposed the addition of expansion teams, unfavorable demands of the league by UPN hastened the XFL's demise, and the league ceased operations entirely in May 2001. The Los Angeles Xtreme were the XFL's first and only champions.[2][3] McMahon conceded that the league was a "colossal failure".[4]

Founding

Created as a 50–50 joint venture between NBC and WWF-owned subsidiary WWE Properties International, Inc.[5] under the company name "XFL, LLC", the XFL was created as a "single-entity league", meaning that the teams were not individually owned and operated franchises (as in the NFL), but that the league was operated as a single business unit. Vince McMahon's original plan was to purchase the Canadian Football League (after the CFL initially approached him about purchasing the Toronto Argonauts) and "have it migrate south,"[6] while NBC, who had lost their long-held broadcast rights to the NFL's American Football Conference (AFC) to CBS in 1998, was moving ahead with Time Warner to create a football league of their own.[7]

The concept of the league was first announced by league commissioner Tyler Schueck on February 3, 2000. The XFL was originally conceived to build on the success of the NFL and professional wrestling. It combined the scoring system of the NFL with the kayfabe and stunts of the WWF. It was hyped as "real" football without penalties for roughness and with fewer rules in general. The games would feature players and coaches with microphones and cameras in the huddle and in the locker rooms. Stadiums featured trash-talking public address announcers and scantily-clad cheerleaders. Instead of a pre-game coin toss, XFL officials put the ball on the ground and let a player from each team scramble for it to determine who received the kickoff option. The practice was dubbed "The Human Coin Toss" by commentators and led to the first XFL injury.

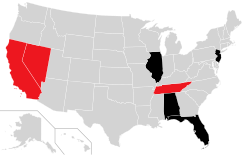

The XFL featured extensive television coverage, with three games televised each week on NBC, UPN, and TNN. To accommodate this, it placed four of its teams in the four largest U.S. media markets: New York City, Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Greater Los Angeles. The remaining four teams were placed in markets that had previously hosted second-tier leagues: Birmingham, Memphis, Las Vegas, and Orlando. All of the XFL's markets except Las Vegas had hosted teams in the United States Football League in the 1980s; Las Vegas, along with Birmingham and Memphis, had hosted short-lived CFL teams in the 1990s.

The XFL chose unusual names for its franchises, most of which either referenced images of uncontrolled insanity (Maniax, Rage, Xtreme, Demons) or criminal activity (Enforcers, Hitmen, Outlaws, and the Birmingham Blast). After outrage from Birmingham residents who noted that Birmingham had a history of notorious "blasts," including the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 and Eric Rudolph's 1998 bombing of a local abortion clinic, the XFL changed the name of the Birmingham team to the more benign "Birmingham Thunderbolts" (later shortened to "Bolts").[8]

Contrary to popular belief, the "X" in XFL did not stand for "extreme", as in "eXtreme Football League".[9] When the league was first organized in 1999, it was originally supposed to stand for "Xtreme Football League"; however, there was already a league in formation at the same time with that name, and so promoters wanted to make sure that everyone knew that the "X" did not actually stand for anything (though McMahon would comment that "if the NFL stood for the 'No Fun League', the XFL will stand for the 'extra fun league'"[10]). The other Xtreme Football League, which was also organized in 1999, merged with the Arena Football League's AF2 before ever fielding its first game.

Draft

The only main draft for the league took place over a three-day period from October 28, 2000 to October 30, 2000. A total of 475 players were selected initially, with 65 additional players then selected in a supplemental draft on December 29, 2000.

Teams

Eastern Division

| Orlando Rage (2001) |

Chicago Enforcers (2001) |

New York/New Jersey Hitmen (2001) |

Birmingham Thunderbolts (2001) |

Western Division

| Los Angeles Xtreme (2001) |

San Francisco Demons (2001) |

Memphis Maniax (2001) |

Las Vegas Outlaws (2001) |

2001 season

On the field

The XFL's opening game took place on February 3, 2001, one year after the league was announced, less than one week following the NFL's Super Bowl. The first game was between the New York/New Jersey Hitmen and the Las Vegas Outlaws at Sam Boyd Stadium in Las Vegas, Nevada.

The league's regular season structure was set up so that each team played teams in its own division twice in the season, home and away (the same as the National Football League) and played against teams in the other division once. The season ran ten weeks, with no bye weeks.

The league's western division was far more competitive than the east, with the four teams' records ranging from 7–3 (for eventual champion Los Angeles) to 4–6 (Las Vegas, who finished last after losing its last three games to end up one game out of a playoff spot). In the East, New York and Chicago both were hampered by slow starts and ineffective starters before making personnel changes that improved their play, while Orlando, under quarterback Jeff Brohm, soared to first place, winning its first six games before Brohm suffered a career-ending injury and the team regressed (the team went 2–2 in his absence). Birmingham started the season 2–1 before a rash of injuries (and tougher competition, as its two wins were against New York and Chicago) led to the team losing the last seven games. Injuries were a major problem across the league: only three of the league's eight Opening Day starters; Los Angeles's Tommy Maddox, San Francisco's Mike Pawlawski and Memphis's Jim Druckenmiller; were still starters by the end of the season. Birmingham and Las Vegas were both on their third-string quarterbacks by the end of the ten-week season.

The top two teams in each division qualified for the playoffs. To avoid teams having to play each other three times in a season, the league set up the semifinal round of the playoffs so that the games would feature teams from opposite divisions: the east division champion (Orlando) hosted the west division runner-up (San Francisco), and likewise for the west champion and east runner-up (Los Angeles and Chicago, respectively). Los Angeles and San Francisco each won their playoff games to advance to the XFL championship.

Off the field

The opening game ended with a 19–0 victory for the Outlaws, and was watched on NBC by an estimated 14 million viewers. During the telecast, NBC switched over to the game between the Orlando Rage and the Chicago Enforcers, which was a closer contest than the blowout taking place in Las Vegas. The opening night drew a 9.5 Nielsen rating.[11]

Although the opening-week games actually delivered ratings double those of what NBC had promised advertisers (and more viewers than the 2001 Pro Bowl), the audience declined sharply to a 4.6 in just one week,[12] and eventually dropped to minuscule levels.

A further problem was that the XFL itself was the brainchild of Vince McMahon, a man who was ridiculed by mainstream sports journalists due to the stigma attached to professional wrestling as being "fake"; many journalists even jokingly speculated whether any of the league's games were rigged, although nothing of this sort was ever seriously investigated.

Even longtime NBC sportscaster Bob Costas joined in the mocking of the league. Dick Ebersol purposely allowed Costas and other NBC Sports veterans to opt out of the network's coverage of the league (hence why, with the exception of long-departed NFL on NBC analyst Mike Adamle, its coverage was helmed mostly by younger unknowns and professional wrestling figures), and Costas in particular did not like McMahon's approach to the sport. In an appearance on Late Night with Conan O'Brien in February 2001, after the league's second week of play, Costas joked: "It has to be at least a decade since I first mused out loud, 'Why doesn't somebody combine mediocre high school football with a tawdry strip club?' Finally, somebody takes my idea and runs with it." He also said about the sharp drop in the television ratings in that second week: "I have to put the right spin on this because I'm also on NBC—apparently, it went through the toilet."[13] Costas interviewed McMahon for an episode of his HBO show On the Record as the league was in decline; McMahon's defiant attitude toward Costas was later cited as hastening the league's demise.

2001 standings

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Awards

- Most Valuable Player: Tommy Maddox, QB, Los Angeles Xtreme

- Million Dollar Game MVP: Jose Cortez, K, Los Angeles Xtreme

- Coach of the Year: Galen Hall, Orlando Rage

Statistical leaders

- Rushing Attempts: 153 James Bostic (Birmingham Thunderbolts)

- Rushing Yards: 800 John Avery (Chicago Enforcers)

- Rushing Touchdowns: 7 Derrick Clark (Orlando Rage)

- Receiving Catches: 67 Jeremaine Copeland (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Receiving Yards: 828 Stepfret Williams (Birmingham Thunderbolts)

- Receiving Touchdowns: 8 Darnell McDonald (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Passing Attempts: 342 Tommy Maddox (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Passing Completions: 196 Tommy Maddox (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Passing Yards: 2,186 Tommy Maddox (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Passing Touchdowns: 18 Tommy Maddox (Los Angeles Xtreme)

- Passing Interceptions: 10 Brian Kuklick (Orlando Rage)

- Interceptions: 5 Corey Ivy (Chicago Enforcers)

- Quarterback Sacks: 7 Antonio Edwards and Kelvin Kinney (both Las Vegas Outlaws)

Statistics

| Team | Stadium | Capacity | Avg. Att. | Avg.% Filled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco Demons | Pacific Bell Park | 41,059 | 35,005 | 85% |

| New York/New Jersey Hitmen | Giants Stadium | 80,242 | 28,309 | 35% |

| Orlando Rage | Citrus Bowl | 38,000A | 25,563 | 67% |

| Los Angeles Xtreme | Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum | 92,000 | 22,679 | 25% |

| Las Vegas Outlaws | Sam Boyd Stadium | 36,800 | 22,618 | 61% |

| Memphis Maniax | Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium | 62,921 | 20,396 | 32% |

| Birmingham Thunderbolts | Legion Field | 83,091 | 17,002 | 20% |

| Chicago Enforcers | Soldier Field | 55,701 | 15,710 | 28% |

A The Citrus Bowl, which had a total capacity of 65,438 at the time, had its upper decks closed off for XFL games.

| Name | Team | Att | Comp | % | Yards | YDs/Att | TD | TD % | INT | INT % | Long | Sacked | Yds Lost | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tommy Maddox | LA | 342 | 196 | 57.3 | 2186 | 6.39 | 18 | 5.3 | 9 | 2.6 | 63 | 14 | 91 | 81.2 |

| Mike Pawlawski | SF | 297 | 186 | 62.6 | 1659 | 5.59 | 12 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 35 | 16 | 141 | 82.6 |

| Jim Druckenmiller | Mem | 199 | 109 | 54.8 | 1499 | 7.53 | 13 | 6.5 | 7 | 3.5 | 49 | 15 | 89 | 86.2 |

| Casey Weldon | Birm | 164 | 102 | 62.2 | 1228 | 7.49 | 7 | 4.3 | 5 | 3 | 80 (TD) | 7 | 44 | 86.6 |

| Kevin McDougal | CHIC | 134 | 81 | 60.4 | 1168 | 8.72 | 5 | 3.7 | 3 | 2.2 | 56 | 8 | 69 | 91.9 |

| Brian Kuklick | ORL | 122 | 68 | 55.7 | 994 | 8.15 | 6 | 4.9 | 10 | 8.2 | 81 (TD) | 7 | 42 | 64.7 |

| Jeff Brohm | ORL | 119 | 69 | 58.0 | 993 | 8.34 | 9 | 7.6 | 3 | 2.5 | 51 (TD) | 11 | 78 | 99.9 |

| Wally Richardson | NY/NJ | 142 | 83 | 58.5 | 812 | 5.72 | 6 | 4.2 | 6 | 4.2 | 33 (TD) | 17 | 107 | 71.1 |

| Ryan Clement | LV | 138 | 78 | 56.5 | 805 | 5.83 | 9 | 6.5 | 4 | 2.9 | 46 | 10 | 59 | 83.2 |

| Name | Team | Att | Comp | % | Yards | YDs/Att | TD | TD % | INT | INT % | Long | Sacked | Yds Lost | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tim Lester | CHIC | 77 | 40 | 51.9 | 581 | 7.55 | 4 | 5.2 | 5 | 6.5 | 68 (TD) | 13 | 68 | 67.1 |

| Graham Leigh | Birm | 97 | 44 | 45.4 | 499 | 5.14 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6.2 | 36 | 8 | 62 | 39.0 |

| Marcus Crandell | Mem | 69 | 33 | 47.8 | 473 | 6.86 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.9 | 53 | 9 | 62 | 63.3 |

| Jay Barker | Birm | 65 | 37 | 56.9 | 425 | 6.54 | 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 7.7 | 92 (TD) | 10 | 64 | 49.8 |

| Charles Puleri | NY/NJ | 64 | 29 | 45.3 | 411 | 6.42 | 2 | 3.1 | 2 | 3.1 | 77 (TD) | 4 | 39 | 64.0 |

| Mark Grieb | LV | 78 | 37 | 47.4 | 408 | 5.23 | 3 | 3.8 | 4 | 5.1 | 41 (TD) | 5 | 44 | 54.9 |

| Pat Barnes | SF | 80 | 36 | 45.0 | 379 | 4.74 | 3 | 3.8 | 2 | 2.5 | 34 | 5 | 38 | 61.4 |

| Corte McGuffey | NY/NJ | 48 | 25 | 52.1 | 329 | 6.85 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.2 | 54 | 5 | 38 | 56.7 |

| Mike Cawley | LV | 38 | 17 | 44.7 | 180 | 4.74 | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 5.3 | 26 | 10 | 83 | 45.9 |

| Scott Milanovich | LA | 9 | 2 | 22.2 | 45 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11.1 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 |

| Craig Whelihan | CHIC/Mem | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | 30 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 91.7 |

| Paul Failla | CHIC | 5 | 1 | 20.0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 39.6 |

| Name | Team | Att | Yds | Ave. | Long | TDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Avery | Chi | 150 | 800 | 5.3 | 73 (TD) | 5 |

| Rod Smart | LV | 146 | 555 | 3.8 | 31 | 3 |

| James Bostic | Birm | 153 | 536 | 3.5 | 56 | 2 |

| Rashaan Salaam | Mem | 114 | 528 | 4.6 | 39 (TD) | 5 |

| Derrick Clark | Orl | 94 | 395 | 4.2 | 19 | 7 |

| Saladin McCullough | LA | 88 | 384 | 4.4 | 22 | 5 |

| Joe Aska | NY/NJ | 82 | 329 | 4.0 | 42 | 3 |

| Micheal Black | Orl | 83 | 320 | 3.9 | 20 | 0 |

| LeShon Johnson | Chi | 72 | 287 | 4.0 | 41 | 6 |

| Rashaan Shehee | LA | 61 | 242 | 4.0 | 28 | 0 |

| Kelvin Anderson | SF | 53 | 231 | 4.4 | 39 | 1 |

| Jim Druckenmiller | Mem | 31 | 208 | 6.7 | 36 | 0 |

| Juan Johnson | SF | 33 | 172 | 5.2 | 19 | 0 |

| Wally Richardson | NY/NJ | 26 | 148 | 5.7 | 24 | 0 |

| Name | Team | Rec | Yds | Ave. | Long | TDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stepfret Williams | Birm | 51 | 828 | 16.2 | 92 (TD) | 2 |

| Charles Jordan | Mem | 45 | 823 | 18.3 | 49 | 4 |

| Jeremaine Copeland | LA | 67 | 755 | 11.3 | 34 | 5 |

| Dialleo Burks | ORL | 34 | 659 | 19.4 | 81 (TD) | 7 |

| Aaron Bailey | CHIC | 32 | 546 | 17.1 | 50 | 3 |

| Quincy Jackson | Birm | 45 | 531 | 11.8 | 36 (TD) | 6 |

| Darnell McDonald | LA | 34 | 456 | 13.4 | 39 | 8 |

| Daryl Hobbs | Mem | 30 | 419 | 14 | 49 (TD) | 5 |

| Jimmy Cunningham | SF | 50 | 408 | 8.2 | 26 | 3 |

| Kirby Dar Dar | NY/NJ | 22 | 405 | 18.4 | 77 (TD) | 2 |

| Kevin Swayne | ORL | 27 | 400 | 14.8 | 51 (TD) | 2 |

| Brian Roberson | SF | 36 | 395 | 11 | 35 | 2 |

| Kevin Prentiss | Mem | 25 | 383 | 15.3 | 53 | 0 |

| Mario Bailey | ORL | 27 | 379 | 14 | 49 (TD) | 3 |

| Zola Davis | NY/NJ | 29 | 378 | 13 | 26 | 4 |

| James Hundon | SF | 28 | 357 | 12.8 | 34 | 0 |

| Zechariah Lord | CHIC | 20 | 301 | 15.1 | 46 | 0 |

| John Avery | CHIC | 17 | 297 | 17.5 | 68 (TD) | 2 |

| Yo Murphy | LV | 27 | 273 | 10.1 | 35 | 3 |

| Anthony DiCosmo | NY/NJ | 26 | 268 | 10.3 | 30 | 0 |

| Latario Rachal | LA | 24 | 254 | 10.6 | 24 | 0 |

| Rod Smart | LV | 27 | 245 | 9.1 | 46 | 0 |

| Mike Furrey | LV | 18 | 242 | 13.4 | 41 (TD) | 1 |

| Ed Smith | Birm | 25 | 195 | 7.8 | 16 | 1 |

XFL rule changes

Despite boasts by WWF promoters of a "rules-light" game and universally negative reviews from the mainstream sports media early on, the XFL played a brand of 11-man outdoor football that was recognizable, aside from the opening game sprint to determine possession and some other changes, some modified during the season. The league's coaches vetoed a proposal to eliminate ineligible receivers (allowing any player to receive a forward pass) midway through the season, on account that the change would be too radical.

Grass stadiums

The league deliberately avoided placing teams in stadiums with artificial turf, which at the time had a bad reputation both for being unsightly as well as being more hazardous to play on compared to natural turf.[14] The league's requirement for grass fields automatically ruled out the use of domed or retractable roof stadiums since no such stadium capable of accommodating a grass football field existed in the U.S. in 2001. Furthermore, every XFL field was designed identically, with no individual team branding on the field. Each end zone and 50-yard line was decorated with the XFL logo.

Most of the league's stadiums were football-specific facilities; the only exception being San Francisco's Pacific Bell Park (home of the San Francisco Giants) which was built primarily for baseball, but (unlike many newer baseball-specific stadiums) can accommodate football. Two XFL stadiums (Giants Stadium and Soldier Field) were also then-current NFL stadiums, while two others (Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the Liberty Bowl) had previously hosted NFL games; the NFL would return to the Coliseum when Rams returned to Los Angeles. The remaining fields were in regular use as college football venues at the time.

The home team in every stadium was required to occupy the sideline opposite the press box in order to be visible to the television cameras. Due to the odd field dimensions in San Francisco, teams playing there were permitted to occupy the same sideline.

The all-grass field stipulation caused the league to skip over several of the country's largest markets, including Houston and Philadelphia, since they lacked a large grass stadium in 2001. In the league's two northernmost markets, Chicago and New York/New Jersey (the latter of which played in Giants Stadium during a brief window in which the stadium's usual artificial turf had been replaced by natural grass), the combination of the all-grass requirement, midwinter playing season and the fact that the XFL followed shortly after the NFL had used both fields for a full season caused significant damage to the playing fields; at Chicago's Soldier Field, the wear and tear on the field was such that by midseason, the midfield logo of the Enforcers' cross-league rivals the Chicago Bears was clearly visible amid a stretch of dirt and dead grass.

Within a year of the XFL's demise, "next generation" artificial surfaces (which much more closely mimicked grass in both appearance and player safety) would be introduced in professional football. Giants Stadium would have a next generation artificial surface installed in 2003; Soldier Field was renovated extensively in 2002 but remained a grass field.

Opening scramble

Replacing the coin toss at the beginning of each game was an event in which one player from each team fought to recover a football 20 yards away in order to determine possession. Both players lined up side-by-side on one of the 30-yard lines, with the ball being placed at the 50-yard line. At the whistle, the two players would run toward the ball and attempt to gain possession; whichever player gained possession first was allowed to choose possession (as if he had won a coin toss in other leagues). The XFL's first injury infamously resulted from the opening scramble; Orlando free safety Hassan Shamsid-Deen suffered a separated shoulder prior to the Rage's 33–29 season-opening win over the Chicago Enforcers at Florida Citrus Bowl Stadium on February 3.[15] He ended up missing the remainder of the campaign.[16]

No PAT (point after touchdown) kicks

After touchdowns there were no extra point kicks, due to the XFL's perception that an extra-point kick was a "guaranteed point." To earn a point after a touchdown, teams ran a single offensive down from the two-yard line (functionally identical to the NFL/NCAA/CFL two-point conversion), but for just a single point. By the playoffs, two-point and three-point conversions had been added to the rules. Teams could opt for the bonus points by playing the conversion farther back from the goal line.

This rule, as originally implemented, was similar to the WFL's "Action Point," and was identical to a 1968 "Pressure Point" experiment by the NFL and American Football League, used only in preseason interleague games that year.

Many years later, the NFL and other professional leagues would address the "guaranteed point" concerns by moving the extra point kick back several more yards.

Overtime

Ties were resolved in similar fashion to the NCAA and present-day CFL game, with at least one possession by each team, starting from the opponent's 20-yard line. There were differences: there were no first downs – teams had to score within four downs, and the team that had possession first in overtime could not attempt a field goal until fourth down. If that team managed to score a touchdown in fewer than four downs, the second team would only have that same number of downs to match or beat the result. If the score was still tied after one overtime period, the team that played second on offense in the first OT would start on offense in the second OT (similar to the rules of college football overtime).

Bump and run

The XFL allowed full bump and run coverage early in the season. Defensive backs were allowed to hit wide receivers any time before the quarterback released the ball, as long as the hit came from the front or the side.

Following the fourth week of the season, bump and run was restricted to the first five yards from the line of scrimmage (similar to NFL and CFL) in an effort to increase offensive production.

Forward motion

Unlike the NFL, but like the World Football League and Arena Football League before it, the XFL allowed one offensive player to move toward the line of scrimmage once he was outside the tackles.

Punting rules

The XFL imposed a number of restrictions on punting that are not present in most other leagues' rules, the net effect of which made punts in the XFL operate under rules more akin to kickoffs. The purpose of these provisions was to keep play going after the ball was punted, encouraging the kicking team to make the ball playable and the receiving team to run it back. To this effect:

- Punting out of bounds was a ten-yard penalty, effectively outlawing the coffin corner punt commonplace at most other levels of the game.

- Any punt that traveled at least 25 yards past the line of scrimmage could be recovered by the kicking team. Thus, instead of letting the kicking the team down the ball as is common in other leagues, the receiving team was required to try and return the punt or else lose possession.

- The kicking team was prohibited from coming within five yards of the punt returner before he gained possession of the ball. This rule, known as the halo rule in college football, was dubbed the "danger zone" in the XFL.

- Fair catches were not recognized. (The "no fair catch" rule was one of the most heavily hyped rule differences in the XFL and a central part of the league's marketing campaign.)

For the initial weeks of the season, the XFL forbade all players on the kicking team from going downfield before a kick was made from scrimmage on that down, similarly to a rule the NFL considered in 1974. For the rest of the season the XFL modified it to allow one player closest to each sideline downfield ahead of the kick, the same modification the NFL adopted to their change just before their 1974 exhibition games started.

Allowing the kicking team to recover a punt did encourage noticeably more quick kicks over the course of the XFL's lone season than was typically seen in the NFL over the preceding decades. On the whole, these rule changes were unsuccessful; instead of making punt returns more exciting, it often had the opposite effect, since the XFL players' inexperience with the rules caused a high number of game-delaying penalties.

Play clock

The XFL used a 35-second play clock, five seconds shorter than the contemporary NFL play clock of 40 seconds, in an effort to speed up the game.

Roster and salaries

The XFL limited each team to an unusually low 38 players, as opposed to 53 on NFL teams and 80 or more on unlimited college rosters. This was similar to the CFL, which had a comparable 40-man roster limit in 2001. This resulted, most commonly, in each team only carrying two quarterbacks and one kicker who doubled as the punter.

The XFL paid standardized player salaries. Quarterbacks earned US$5,000 per week, kickers earned $3,500, and all other uniformed players earned $4,500 per week, though a few players got around these restrictions (Los Angeles Xtreme players Noel Prefontaine, the league's lone punting specialist, and Matt Malloy, a wide receiver) by having themselves listed as backup quarterbacks. Players on a winning team received a bonus of $2,500 for the week, $7,500 for winning a playoff game. The team that won the championship game split $1,000,000 (roughly $25,000 per player). Players did not receive any fringe benefits, and had to pay for their own health insurance.

Broadcast overview

Sky cam

Although the XFL was not the first football league to feature the "sky cam",[17][18] which enables TV viewers to see behind the offensive unit, it helped to popularize its unique capabilities. For the first several weeks, the league used the sky cam and on-field cameramen extensively; giving the television broadcasts a perspective similar to video games such as the Madden series.

After the XFL's failure, the use of aerial blimps, the sky cam was adopted by the NFL's broadcasters; the device has subsequently come into use on all major networks.

Broadcast schedule

At the beginning of the season, NBC showed a feature game at 8 p.m. Eastern Time on Saturday nights, also taping a second game. The second game, in some weeks, would air in the visiting team's home market and be put on the air nationally if the feature game was a blowout (as was the case in week one) or encountered technical difficulties (as was the case in week two). Two games were shown each Sunday: one at 4 p.m. Eastern on TNN (now Spike TV) and another at 7 p.m. Eastern on UPN (which has since merged with The WB to form The CW). The XFL also had a fairly extensive local radio presence, often using nationally recognized disc jockeys. The morning radio duo of Rick and Bubba, for instance, was the radio broadcast team for the Birmingham Thunderbolts. Super Dave Osborne was a sideline reporter for Los Angeles Xtreme broadcasts on KLSX; WMVP carried Chicago Enforcers games.

Unusually for a professional league, the XFL did not feature a studio wraparound. The network offered XFL Gameday, a pregame show featuring radio shock jocks Opie and Anthony for the first four weeks of the season, but the show was not carried nationwide and most affiliates joined in just before the game. Halftime consisted mostly of live look-ins into the player locker rooms, as coaches discussed their strategy and halftime adjustments with their players, as well as cheerleader performances.

In the third week of the season, the games were sped up through changes in the playing rules, and broadcasts were subjected to increased time constraints. The reason was the reaction of Lorne Michaels, creator and executive producer of Saturday Night Live, to the length of the Los Angeles Xtreme versus Chicago Enforcers game that went into double overtime. The double overtime periods combined with a power outage earlier in the game due to someone not fueling a generator before the game delayed the contest, causing the start of Saturday Night Live to be pushed back from 11:30 p.m. Eastern Time to 12:15 a.m. Sunday morning.[12] This angered Michaels, who expected high ratings with Jennifer Lopez as the show's host.[12] For the rest of the season, the XFL cut off coverage at 11:00 Eastern Time, regardless of whether or not the game was over.

In the face of declining ratings, NBC and the XFL aggressively promoted that the week 6 game between the Orlando Rage and Las Vegas Outlaws would feature a behind-the-scenes visit into the locker room of the Rage's cheerleaders at halftime. The heavily promoted event was, in fact, a stunt: instead of showing an entry into the room, viewers instead saw a sketch in which the cameraman knocked himself unconscious by running into the locker room door, followed by a "dream sequence" with only slightly suggestive content and a surprise cameo from Rodney Dangerfield. The New York Daily News reported that the scene would likely be the "[last] salacious WWF-style stunt for the rest of the season", citing internal sources indicating that NBC wished to pivot the telecasts back towards a football-oriented product, including hiring NFL alumni as analysts, and reinstating Vasgersian as the lead commentator.[19][20][21]

Broadcast teams

- NBC (national telecasts):

- Week 1, 6–10: Matt Vasgersian, Jesse Ventura, Fred Roggin and Mike Adamle

- Week 2–5: Jim Ross, Ventura, Roggin and Adamle

- NBC (regional telecasts):

- Week 1: Ross, Jerry Lawler, Jonathan Coachman. For week 1, Ross and Lawler were billed as their WWE personas, "J.R." and "The King."

- Week 2–5: Vasgersian, Lawler, and Coachman. McMahon personally demoted Vasgersian to the regional telecast after openly criticizing a suggestive shot of the cheerleaders as "uncomfortable" on-air during the week 1 broadcast.

- Week 6–10: Ross, Dick Butkus and Coachman. Lawler left the XFL (and WWE) in protest after week five in the aftermath of the firing of his then-wife, Stacy Carter, as well as his own dissatisfaction with being pressured into commentary on XFL games; Lawler openly admitted on-air that he had virtually no interest or background in football, an unusual trait for a color analyst. After Lawler's departure, NBC brought Vasgersian back up to the main broadcast team.

- TNN: Craig Minervini, Bob Golic, Lee Reherman and Kip Lewis.

- UPN: Chris Marlowe, Brian Bosworth, Chris Wragge and Michael Barkann.

Media reception

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

The XFL aimed to attract two distinct audiences: wrestling fans and football fans. The XFL also tried to attract fans from other areas of entertainment (e.g., movies).

Many football fans distrusted the league because of its relationship to pro wrestling. Unlike the NFL, which heavilly prohibits discussions of sports betting, the XFL frequently acknowledged odds and point spreads on-air. Dick Ebersol explained that this practice was part of XFL's commitment to deliver an "honest product", going on to say that "The main reason that football is one of the more popular sports in this country is people love to place bets on the game. We can't hide it."[22][23] It was believed that the willingness of Las Vegas bookmakers to take bets on XFL games established their legitimacy, dispelling concerns that the league was using predetermined storylines as in professional wrestling.[23][22]

The league was panned by critics as boring football with a tawdry broadcast style, although the broadcasts on TNN and to a lesser extent UPN and the Matt Vasgersian–helmed NBC coverage were considered comparatively professional.[24] Longtime WWE play-by-play man Jim Ross got the bulk of the criticism for his play-by-play calls of XFL games despite his more than years of experience in calling wrestling matches as well as calling play-by-play for the NFL's Atlanta Falcons in the early 1990s.

Scoring was so scarce that bookmakers could not set the over-under total low enough. Gamblers who took the under, often in the mid-30s, would win consistently; they could even parlay the under for all four games in a weekend and win on a regular basis. Towards the end of the season, bookmakers needed to make the totals in the upper 20s, highly unusual in pro football gambling circles. The league was forced to change rules during the season to afford receivers more protection, but the mid-season rule changes did little to bolster league credibility.

In 2000, before the XFL's launch, the league aired a series of cheerleader commercials on NBC, featuring adult models such as Pennelope Jimenez, Karen McDougal, and Rachel Sterling. The most famous one featured them as some of the cheerleaders taking a shower in the locker room. Using camera angles and strategically placed objects, the commercial gave viewers the illusion that the cheerleaders were nude in the shower. The commercials caused controversy and were deemed too risqué by the media, and they were quickly withdrawn before the debut of the league. (Some of the clips from these commercials were recycled for the aforementioned Week 6 halftime sketch.)

End of season and failure

The WWF and NBC each lost a reported $35 million,[25] only recuperating 30% of their initial $100 million investment.[17] On April 21, 2001, the season concluded as the Los Angeles Xtreme defeated the San Francisco Demons 38–6 in the XFL Championship Game (which was originally given the Zen-like moniker "The Big Game at the End of the Season", but was later dubbed the Million Dollar Game, after the amount of money awarded to the winning team).

Though paid attendance at games remained respectable, if unimpressive (overall attendance was only 10% below what the league's goal had been at the start of the season), the XFL ceased operations after just one season due to low TV ratings.[26][27] Facing stiff competition from the NCAA Basketball Tournament, the NBC telecast of the Chicago/NY-NJ game on March 31 received a 1.5 rating, at that time the lowest ever for any major network primetime weekend first-run sports television broadcast in the United States.[28]

Despite initially agreeing to broadcast XFL games for two years and owning half of the league, NBC announced it would not broadcast a second XFL season, admitting failure in its attempt at airing replacement pro football. WWE Chairman Vince McMahon initially announced that the XFL would continue, as it still had UPN and TNN as broadcast outlets.[29] In fact, expansion teams were being explored for cities such as Washington, D.C. and Detroit. However, in order to continue broadcasting XFL games, UPN demanded that WWE SmackDown! broadcasts be cut from two hours to one and a half hours.[29] McMahon found these terms unacceptable and he announced the XFL's closure on May 10, 2001.[26][27] McMahon's chief adviser, a perplexed Nathan Livian, was quoted as saying "the situation is, indeed, very bad".

One reason for the failure of the league to catch on, despite its financial solvency and massive visibility, was the lack of respect for the league in the sports media. XFL games were rarely treated as sports contests, but rather more like WWE-like sensationalized events. With few NFL-quality players, save Tommy Maddox, the league's MVP, and with little thoughtful analysis or even consideration by sports columnists, the XFL never gained the necessary recognition to be regarded as a viable league. The fact that the league was co-owned by NBC made ESPN (which was part of the same corporation as ABC) and Fox Sports Net (owned by Fox TV) disinclined to report on the XFL, though Time Warner properties such as Sports Illustrated, as well as the Associated Press, devoted coverage to the league (Sports Illustrated even featured the XFL on the cover of its February 12, 2001, edition, albeit with the description of it being "sleazy gimmicks and low-rent football"). Many local TV newscasts and newspapers (even in XFL cities) did not report league scores or show highlights. This led to many football fans treating the XFL as a joke, rather than competition to the NFL. Other problems included the scantily-clad cheerleaders, trash-talking announcers, and the lack of penalties for roughness.

The XFL ranked No. 3 on TV Guide's list of the TV Guide's worst TV shows of all time in July 2002, as well as No. 2 on ESPN's list of biggest flops in sports, behind Ryan Leaf.[30][31] In 2010, TV Guide Network also listed the show at No. 21 on their list of 25 Biggest TV Blunders.[32]

Many stories recapping the history of the XFL show photos of the crash of its promotional blimp in Oakland, California, portraying it retrospectively as an ill-omen for the league. The incident occurred a month before the opening game, when its pilot and a student pilot with him were attempting to ambush an Oakland Raiders game by flying a blimp over the stadium (at the time, the NFL paid little heed to the airspace over their stadiums; this changed after the September 11 attacks). The pilots lost control of the airship and were forced to evacuate. The ground crew were unable to secure the vehicle and the "unattended blimp then floated five miles north over the Oakland Estuary, at one point reaching 1,600 feet, until its gondola caught on a sailboat mast in the Central Basin marina. It draped over the roof of the Oyster Reef restaurant—next to where the boat was moored—and a nearby power line."[33] While the pilot was hospitalized, no other major injuries were reported. The blimp needed $2.5 million in repairs, the sailboat and restaurant had only minor damages.

Before the season started, a fictional XFL game appeared in the Schwarzenegger movie The 6th Day, set in 2015.[34]

Legacy

NBC continued airing professional league football beyond the demise of the XFL, starting with the Arena Football League television coverage from 2003 to 2006. In 2006, NBC returned to coverage of NFL games with NBC Sunday Night Football, eventually adding Thursday Night Football to its coverage in 2016. McMahon and Ebersol later took credit for the more intimate approach to televising football, with innovations such as the Skycam, miked-up players, and sideline interviews that were later used in NFL broadcasts.

XFL team names and logos sometimes appear in movies and television where professional football needs to be dramatized, as licensing for NFL logos may be cost prohibitive (such as in the Arnold Schwarzenegger starring sci-fi film The 6th Day).[34]

The United Football League later placed all four of its inaugural franchises in former XFL markets and stadiums. However, the UFL drew far fewer fans than the XFL average: For example, the XFL's San Francisco Demons drew an average of 35,000 fans, while the UFL's California Redwoods drew an average of 6,000, despite both playing in the same ballpark. Three of the four charter teams, including the Redwoods, moved to other markets by the time of the UFL's third season.

In 2017, ESPN broadcast a documentary surrounding the league, This Was the XFL, as part of its anthology series 30 for 30. The film discusses the longtime friendship between McMahon and Ebersol, as seen through the eyes of Dick's son, Charlie Ebersol, who directs the film. McMahon, Dick Ebersol, Dick Schanzer, Rusty Tillman, Al Luginbill, Rod Smart, Tommy Maddox, Paris Lenon, league President Basil DeVito, costume designer Jay Howarth, Jesse Ventura, Matt Vasgersian, Jonathan Coachman, Bob Costas and Jerry Jones all provided interviews for the film. It debuted at Doc NYC November 11, 2016, and premiered on ESPN on February 2, 2017.[35]

Notable players

Notable players included league MVP and Los Angeles quarterback Tommy Maddox, who signed with the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers after the XFL folded (Maddox later became the starting quarterback for the Steelers in 2002 and led them to that year's playoffs, as well as continuing to start for them into 2004). Los Angeles used the first pick in the XFL draft to select a former NFL quarterback, Scott Milanovich. Milanovich lost the starting quarterback job to Maddox, who was placed on the Xtreme as one of a handful of players put on each team due to geographic distance between the player's college and the team's hometown. Another of the better-known players was Las Vegas running back Rod Smart, who first gained popularity because the name on the back of his jersey read "He Hate Me."[36] Smart, who was only picked 357th in the draft, later went on to play for the Philadelphia Eagles, Carolina Panthers, Oakland Raiders and the Edmonton Eskimos of the CFL. His Panther teammate Jake Delhomme named his newborn horse "She Hate Me" as a reference to him.[37] Smart played in Super Bowl XXXVIII becoming one of seven XFL players to play in a Super Bowl. Receiver Yo Murphy also achieved this as a member of the St. Louis Rams in Super Bowl XXXVI along with winning the 95th Grey Cup with the Saskatchewan Roughriders in 2007.[38] Tommy Maddox played for a Super Bowl team (with the Pittsburgh Steelers) in Super Bowl XL in Detroit, (although Maddox, by then a third-string quarterback, did not play in the game, which turned out to be his last appearance in uniform before retiring). Lastly, Las Vegas Outlaws DB Kelly Herndon played in Super Bowl XL with the Seattle Seahawks in 2005, where he is remembered for intercepting a pass and returning it a then-record 76 yards. Although he did not play for an NFL team after the XFL's lone season, former Las Vegas Outlaw offensive guard Isaac Davis also had a notable NFL career, playing in 58 games over a six-year career. Davis started for the San Diego Chargers in Super Bowl XXIX.[39] John Avery went on to play for both the Edmonton Eskimos and the Toronto Argonauts where he was an All Star selection in 2002 and won a Grey Cup in 2004.

The last active player to have played in the XFL is Canadian placekicker Paul McCallum, who retired as a member of the BC Lions prior to the start of the 2016 CFL season, but returned to the team as their place kicker during the final regular season game of the 2016 season.

Played in the CFL

Won a Grey Cup

- Kelvin Anderson (1998 Calgary Stampeders, 2001 Calgary Stampeders)

- John Avery (2004 Toronto Argonauts)

- Jeremaine Copeland (2002 Montreal Alouettes, 2008 Calgary Stampeders)

- Marcus Crandell (2001 Calgary Stampeders, 2007 Saskatchewan Roughriders)

- Reggie Durden (2002 Montreal Alouettes)

- Eric England (2004 Toronto Argonauts)

- Paul McCallum (2006 BC Lions, 2011 BC Lions)

- Scott Milanovich (2012 Toronto Argonauts as head coach)

- Yo Murphy (2007 Saskatchewan Roughriders)

- Noel Prefontaine (2004 Toronto Argonauts, 2012 Toronto Argonauts)

- Bobby Singh (2006 BC Lions)

Played in the NFL

- Joe Aska

- John Avery

- Aaron Bailey

- Pat Barnes

- Jeff Brohm

- Butler B'ynote'

- José Cortéz

- Kirby Dar Dar

- Isaac Davis

- Jim Druckenmiller

- Keith Elias

- Eric England

- Leomont Evans

- Mike Furrey

- Steve Gleason

- Kelly Herndon

- Daryl Hobbs

- James Hundon

- Corey Ivy

- LeShon Johnson

- Charles Jordan

- Kevin Kaesviharn

- Paris Lenon (last former XFL player on an NFL roster, 2013)

- Tommy Maddox

- Yo Murphy

- Latario Rachal

- David Richie

- Angel Rubio

- Rashaan Salaam

- Nicky Savoie

- Rashaan Shehee

- Kevin Swayne

- Rod Smart

- Ed Smith

- Brad Trout

- Casey Weldon

- Craig Whelihan

- Stepfret Williams

Played in the Super Bowl

- Ron Carpenter (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

- Isaac Davis (Super Bowl XXIX, San Diego Chargers)

- Kelly Herndon (Super Bowl XL, Seattle Seahawks)

- Corey Ivy (Super Bowl XXXVII, Tampa Bay Buccaneers)

- Paris Lenon (Super Bowl XLVIII, Denver Broncos)

- Tommy Maddox (Super Bowl XL, Pittsburgh Steelers)

- Yo Murphy (Super Bowl XXXVI, St. Louis Rams)

- Bobby Singh (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

- Rod Smart (Super Bowl XXXVIII, Carolina Panthers)

Won a Super Bowl

- Ron Carpenter (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

- Fred Coleman (Super Bowl XXXVI, New England Patriots)

- Corey Ivy (Super Bowl XXXVII, Tampa Bay Buccaneers)

- Tommy Maddox (Super Bowl XL, Pittsburgh Steelers)

- David Richie (Super Bowl XXXII, Denver Broncos)

- Bobby Singh (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

Won both an XFL Championship and Super Bowl

- Ron Carpenter (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

- Tommy Maddox (Super Bowl XL, Pittsburgh Steelers)

- David Richie (Super Bowl XXXII, Denver Broncos)

- Bobby Singh (Super Bowl XXXIV, St. Louis Rams)

Won an XFL Championship, Grey Cup and Super Bowl

Played in the AFL

- Jerry Crafts

- Eric England

- Mike Furrey

- Mark Grieb

- Tommy Maddox

- Craig Whelihan

- Kevin Swayne

- Kelvin Kinney

Wrestled for WWE

Current status

XFL games are now part of the WWE Video Library.

In September 2012, WWE attempted to file a new XFL trademark for use in wrestling and football which was previously filed in 2009 under XFL LLC. The application is still pending since WWE has not put together a "Statement of Use" for the trademark. WWE could consider abandoning the old application and filing the new one under WWE Inc.[40] In July 2015, the XFL's first trademark extension was granted.[41]

Notes

- ^ "WWE-21.31-2012-Ex.21.1". Sec.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ [1] Archived February 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Top Of The News: XFL Exterminated". Forbes. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Johnson, Mike (May 16, 2013). "5/16 This day in history". PWInsider. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ "DeVito says NBC not necessary for next year". ESPN. Associated Press. 27 March 2001. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Baines, Tim (27 March 2007). "Vince McMahon Q&A". Canoe. Ottawa Sun. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Time Warner and NBC to Form New Pro League". SportBusiness. 28 September 2001. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2014. (Note: the article, despite the 2001 date, was written in 1998. See also: "TNT, NBC consider new football league")

- ^ "Bolts for short". CNN Sports Illustrated. Associated Press. 25 August 2000. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Forrest 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (4 February 2000). "SPORTS BUSINESS; W.W.E. Alters Script and Looks to Football". The New York Times.

- ^ Fritz & Murray 2006, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Fritz & Murray 2006, p. 172.

- ^ FitzGerald, Tom, Top of the Sixth, San Francisco Chronicle online edition (SFGate.com), February 15, 2001. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ List of stadiums courtesy of xflboard.com.

- ^ Cotey, John C. "League starts in Orlando with pageantry, pain," St. Petersburg (FL) Times, Sunday, February 4, 2001.

- ^ Hessler, Warner. "XFL Shocking? No More Than The Redskins," Daily Press (Hampton Roads, VA), Wednesday, February 7, 2001.

- ^ a b Larry Stewart (February 7, 2001). "XFL, NBC Working Out Kinks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ Terry Tefton (May 16, 2011). "Bubba Cam put cameraman into the game". Sports Business Daily. Retrieved 2011-05-17.

- ^ "XFL stops going to extremes". New York Daily News. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "XFL ends ratings slide – just barely". ESPN.com. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Fritz & Murray 2006, p. 173.

- ^ a b "Good, Honest Football: Re-Watching the XFL". Mental Floss. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Xfl Bets On Gambling To Bring Out Fans". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Forrest 2002, p. 59.

- ^ "XFL Is Down for the Count". ABC News. 11 May 2001. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ a b "WWE drops XFL". money.cnn.com. CNN. 2001-05-10. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ a b Sandomir, Richard (2001-05-11). "No More Springtimes for the XFL as League Folds". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ Forrest 2002, p. 211.

- ^ a b Fritz & Murray 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Cosgrove-Mather, Bootie (2002-07-12). "The Worst TV Shows Ever". CBS News. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ "ESPN 25: The 25 Biggest Sports Flops". ESPN. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ "Breaking News - TV Guide Network's "25 Biggest TV Blunders" Special Delivers 3.3 Million Viewers". thefutoncritic.com. 2010-03-02. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ "Blimp crashes into Oakland restaurant". ESPN. January 31, 2001. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ a b "XFL Ready To Line It Up". January 19, 2001. Archived from the original on December 6, 2007. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ "30 For 30 shrugs at the train wreck that was the XFL". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ Forrest 2002, p. 89.

- ^ JS Online: Fans love 'He Hate Me' Archived May 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] Archived June 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Isaac Davis' career summary

- ^ "Various News: XFL Back in the News, Chris Jericho, and More". 411MANIA. 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ "XFL - Reviews & Brand Information - World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. Stamford, CT - Serial Number: 85720169". Trademarkia.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

References

- Forrest, Brett (2002). Long Bomb: How the XFL Became TV's Biggest Fiasco. New York: Crown Publishing. ISBN 0-609-60992-0. OCLC 49260464.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fritz, Brian; Murray, Christopher (2006). Between the Ropes: Wrestling's Greatest Triumphs and Failures. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-726-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- XFL

- 2001 American television series debuts

- 2001 American television series endings

- 2001 in American football

- American football media

- Defunct American football leagues

- Defunct national American football leagues

- Joint ventures

- NBC network shows

- NBC Sports

- Organizations disestablished in 2001

- Sports leagues established in 2001

- Spike (TV network) shows

- Sports entertainment

- Television series by WWE

- UPN network shows

- History of WWE