Blue Card (European Union)

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

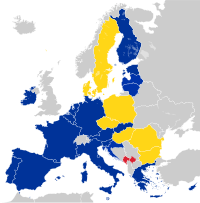

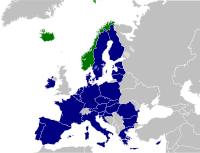

The Blue Card is an approved EU-wide work permit (Council Directive 2009/50/EC)[1] allowing high-skilled non-EU citizens to work and live in any country within the European Union, excluding Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom, which are not subject to the proposal.[2] The term Blue Card was coined by the think tank Bruegel, inspired by the United States' Green Card and making reference to the European flag which is blue with twelve golden stars.[3]

The Blue Card proposal presented by the European Commission offers a one-track procedure for non-EU citizens to apply for a work permit, which would be valid for up to three years, but can be renewed thereafter. Those who are granted a blue card will be given a series of rights, such as favourable family reunification rules. The proposal also encourages geographic mobility within the EU, between different member states, for those who have been granted a blue card. The legal basis for this proposal was Article 63(3)and (4) of the Treaty of Rome (now Article 79 TFEU).

Proposal

The blue card proposal was presented at a press conference in Strasbourg on 23 October 2007, by the President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso and Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security Franco Frattini. Barroso explained the motives behind the proposal as: The EU’s future lack of labour and skills; the difficulty for third country workers to move between different member states for work purposes; the conflicting admission procedures for the 27 different member states, and the "rights gap" between EU citizens and legal immigrants.[4] The proposal was presented along with another proposal, COM(2007)638, which includes a simplified application procedure and a common set of rights for legal third-country workers. The name ‘blue card’ is chosen to signal potential immigrants that the blue card is the European alternative to the US Green card.[5] The colour blue is the predominant colour of the European Union.

International reaction

Shortly after the proposal was presented, it received heavy criticism from governments of developing countries, for its perceived functionality in snatching up talents. South African Minister of Health Manto Tshabalala-Msimang pointed to the fact that several African countries already suffer from the migration of skilled health workers and said that this proposal might worsen the situation. Moroccan international economic law professor Tajeddine El Husseini went further, saying that this "is a new form of colonisation, of discrimination, and it will be very hard to find support for it among southern countries".[6]

A 2011 thesis by A. Björklund on Possible Impacts of the EU Blue Card Directive on Developing Countries of Origin through Migration of Skilled Workers[7] with a focus on the Republic of Mali concludes that skilled Malian migrants in general seem to depart with the intention at the outset to return to their home country after a certain period of time, bringing with them significant human capital in the forms of skills, experience, information and a different view on methods of working. During their stay abroad, remittances from expatriates often represent an important source of income to the country of origin.

Approval

On 20 November 2008 the European Parliament backed the introduction of the blue card while recommending some safeguards against brain drain and advocated greater flexibility for EU Member States.[8] Many of these suggestions, though, were ignored in the subsequent legislation which was passed on 25 May 2009. Some compromises were made, as "Member States to set quotas on Blue Card holders or to ban them altogether if they see fit."[citation needed] The Blue Card rules also could run into problems with the European Permanent Residency Directive. Some EU Member States are not in compliance with implementing the EU Blue Card program. Despite having been warned in July 2011, Austria, Cyprus and Greece have not yet transposed the rules of the Blue Card Directive, which should have been implemented before 19 June 2011.[9]

Implementation

Even years after the transposition deadline passed, some Member States (such as Spain and Belgium) have yet to fully enact the law or give the rights fully promised in the directive. Already, think tanks have presented ideas designed to supplement the Blue Card and its weaknesses.[10]

Germany had enacted the Blue Card legislation fully as of April 2012 focusing on language skills and areas of need such as engineering, mathematics and IT.[11] As of January 1, 2014, Germany had given out 7,000 Blue Cards. 4,000 of these were given to foreigners who were already living in Germany.[12]

A dedicated EU Blue Card section was added to the EU Immigration Portal on 7 June 2016.[13] The site provides country-specific information to potential Blue Card applicants. It states that only EU Member State authorities may issue Blue Cards and warns against any unofficial application sites which may contain incorrect information or charge for their services.

Requirements

Acquisition of Blue Card has the following requirements. The applicant must have a work contract or binding job offer[14][15] with a salary of at least 1.5 times the average gross annual salary paid in the Member State. A Blue Card acquirer must present a valid travel document (and in specific cases a valid residence permit or a national long-term visa) and documents proving the relevant higher professional qualification.[16]

References

- ^ "Council Directive 2009/50/EC".

- ^ "Microsoft Word - EN 637 - original.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ Belgium (31 March 2006). "Welcome to Europe" (PDF). Bruegel.org. Retrieved 1 December 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "EUROPA - Rapid - Press Releases". Europa.eu. 23 October 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "The EU Blue Card is Europe's answer to the American Green Card". prweb.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kubosova, Lucia (29 October 2007). "Africa Fears Brain Drain from Blue Card". Businessweek.com. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Skilled workers leaving for the European Union - Possible Impacts of the EU Blue Card Directive on Developing Countries of Origin through Migration of skilled Workers" (PDF). University of Stockholm.

- ^ "MEPs support the European "Blue Card" proposal for highly-skilled immigrants". europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ "Blue Card: Commission warns Member States over red tape facing highly qualified migrants - Proceedings against Malta terminated". http://ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Parkes, Roderick and Steffen Angenendt (2010). "After the Blue Card" (PDF). migration-boell.de. HBS Discussion Paper

- ^ "German 'Blue Card' to simplify immigration". dw.de. 28 April 2012.

- ^ "BA-Chef Weise: Nur 7000 Zuwanderer mit Blue Card". Heise Online (in German). 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Press Release - Delivering the European Agenda on Migration: Commission presents Action Plan on Integration and reforms 'Blue Card' scheme for highly skilled workers from outside the EU". European Commission. 6 June 2016.

- ^ http://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Flyer/flyer-blaue-karte.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ http://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/EN/Publikationen/Flyer/flyer-blaue-karte.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "EU Blue Card, requirements, rights". www.immigration-residency.eu Baltic Legal.

External links

- Official EU Blue Card page on the EU's Immigration Portal

- European Parliament- Blue Card Feature

- Council Directive 2009/50/EC of 25 May 2009

- Discussion about the Blue Card with Focus on Germany

- Building a more attractive Europe. The Blue Card experience by Silvia Mosneaga