Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

| Shuttle Carrier Aircraft | |

|---|---|

| |

| NASA's Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 905 (foreground) and 911 (background) | |

| Role | Outsize cargo freight aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Boeing (aircraft & modifications) |

| Introduction | 1977 |

| Retired | 2012 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | NASA Boeing |

| Number built | 2 (converted ex-commercial aircraft) |

| Developed from | Boeing 747-100 |

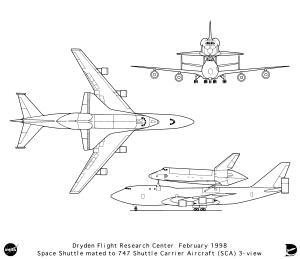

The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) were two extensively modified Boeing 747 airliners that NASA used to transport Space Shuttle orbiters. One is a 747-100, while the other is a 747SR (a short-range variant of the same model).

The SCAs were used to ferry Space Shuttles from landing sites back to the Shuttle Landing Facility at the Kennedy Space Center. The orbiters were placed on top of the SCAs by Mate-Demate Devices, large gantry-like structures that hoisted the orbiters off the ground for post-flight servicing then mated them with the SCAs for ferry flights.

In approach and landing test flights conducted in 1977, the test shuttle Enterprise was released from an SCA during flight and glided to a landing under its own control.[1]

Design and development

The Lockheed C-5 Galaxy was considered for the shuttle-carrier role by NASA, but rejected in favor of the 747—in part due to the 747's low-wing design in comparison to the C-5's high-wing design, and also because the U.S. Air Force would have retained ownership of the C-5, while NASA could own the 747s outright.

The first aircraft, a Boeing 747-123 registered N905NA, was originally manufactured for American Airlines and still carried visible American cheatlines while testing Enterprise in the 1970s. It was acquired in 1974 and initially used for trailing wake vortex research as part of a broader study by NASA Dryden, as well as Shuttle tests involving an F-104 flying in close formation and simulating a "release" from the 747.

The aircraft was extensively modified for NASA by Boeing in 1976.[2] While first-class seats were kept for NASA passengers, its main cabin and insulation were stripped,[3] mounting struts were added, and the fuselage was strengthened. Vertical stabilizers were added to the tail to aid stability when the Orbiter was being carried. The avionics and engines were also upgraded, and an escape tunnel system similar to that used on Boeing's first 747 test flights was added. The flight crew escape tunnel system was later removed following the completion of the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) due to concerns over possible engine ingestion of an escaping crew member.

Flying with the additional drag and weight of the Orbiter imposed significant fuel and altitude penalties. The range was reduced to 1,000 nautical miles (1,850 km), compared to an unladen range of 5500 nautical miles (10,100 km), requiring an SCA to stop several times to refuel on a transcontinental flight.[4] Without the Orbiter, the SCA needed to carry ballast to balance out its center of gravity.[3] The SCA had an altitude ceiling of 15,000 feet and a maximum cruise speed of Mach 0.6 with the orbiter attached.[4] A crew of 170 took a week to prepare the shuttle and SCA for flight.[5]

Studies were conducted to equip the SCA with aerial refueling equipment, a modification already made to the U.S. Air Force E-4 (modified 747-200s) and 747 tanker transports for the IIAF. However, during formation flying with a tanker aircraft to test refueling approaches, minor cracks were spotted on the tailfin of N905NA. While these were not likely to have been caused by the test flights, it was felt that there was no sense taking unnecessary risks. Since there was no urgent need to provide an aerial refueling capacity, the tests were suspended.

By 1983, SCA N905NA no longer carried the distinct American Airlines tricolor cheatline. NASA replaced it with its own livery, consisting of a white fuselage and a single blue cheatline.[6] That year, this aircraft was also used to fly Enterprise on a tour in Europe, with refuelling stops in Goose Bay, Canada; Keflavik, Iceland; England; and West Germany. It then went to the Paris Air Show.[7]

In 1988, in the wake of the Challenger accident, NASA procured a surplus 747SR-46 from Japan Airlines. Registered N911NA it entered service with NASA in 1990 after undergoing modifications similar to N905NA. It was first used in 1991 to ferry the new shuttle Endeavour from the manufacturers in Palmdale, California to Kennedy Space Center.

Based at the Dryden Flight Research Center within Edwards Air Force Base in California[3] the two aircraft were functionally identical, although N911NA has five upper-deck windows on each side, while N905NA has only two. The rear mounting points on both aircraft were labeled with humorous instructions to "attach orbiter here" or "place orbiter here", clarified by the precautionary note "black side down".[8][9]

Shuttle Carriers were capable of operating from alternative shuttle landing sites such as those in the United Kingdom, Spain, and France. Due to the reduced range of the Shuttle Carrier while mated to an orbiter, additional preparations such as removal of the payload from the orbiter may have been necessary to reduce its weight.[10]

Boeing transported its Phantom Ray unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) demonstrator from St. Louis, Missouri, to Edwards on a Shuttle Carrier on December 11, 2010.[11]

Ferry flights

Ferry flights generally transported the orbiters from Edwards Air Force Base, the shuttle's secondary landing site, to the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center where the orbiter was processed. This was common in the early days of the space shuttle program when weather conditions at the SLF prevented the shuttle from landing there. Some flights started at the Dryden Flight Research Center following delivery of the orbiter from Rockwell International to NASA from the nearby facilities in Palmdale, California.[12]

At the end of the space shuttle program the SCA was used to deliver the retired orbiters from the Kennedy Space Center to their museums. Discovery was delivered to the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia, near Washington, D.C. on April 19, 2012. On April 17, 2012, Discovery was flown atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft escorted by a NASA T-38 Talon chase aircraft in a final farewell flight. The 747 and Discovery flew over Washington, D.C. and the metropolitan area around 10 am and arrived at Dulles around 11 am. The flyover and landing were widely covered on national news media.

The last ferry flight took Endeavour from Kennedy Space Center to Los Angeles between 19 and 21 September 2012 via Ellington Field and Edwards Air Force Base. After leaving Edwards the SCA with Endeavour performed low level flyovers above various landmarks across California, from Sacramento to the San Francisco Bay Area, and finally to Los Angeles. Endeavour was delivered to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). From there the orbiter was transported through the streets of Los Angeles and Inglewood to its final destination in the California Science Center in Exposition Park.

Retirement

Shuttle Carrier N911NA retired on February 8, 2012 after its final mission to the Dryden Aircraft Operations Facility in Palmdale, California, and will be used as a source of parts for NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).[13] Meanwhile, N911NA is being loaned out for display to the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark in Palmdale, California, beginning in September 2014.[14]

Shuttle Carrier N905NA was used to ferry the retired Shuttles to their respective museums. It returned to the Dryden Flight Research Facility at Edwards Air Force Base in California after a short flight from Los Angeles International Airport on September 24, 2012. It was intended to join N911NA as a source of spare parts for NASA's SOFIA aircraft.[13][15] NASA engineers surveyed N905NA and determined that it had few parts usable for SOFIA, and 905 is now preserved and on display in Houston. Three former NASA aircraft are on static display in the Houston area - two T-38s at the front entrance of Space Center Houston, and the former NASA KC-135 930 Vomit Comet. In 2013, the Space Center announced plans to display SCA 905 with the mockup shuttle Independence mounted on its back.[16] NASA 905 was erected on site at the space center, having been dismantled and ferried in seven major pieces, (called The Big Move) from Ellington Field, and the replica shuttle was mounted in August 2014.[17]

The display called Independence Plaza opened to the public for the first time on January 23, 2016.

Specifications

Data from Boeing 747-100 specifications[18] Jenkins 2000[4]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4: pilot, co-pilot, 2 flight engineers (1 flight engineer when not carrying Shuttle)

Performance

Image gallery

-

Shuttle Carrier Aircraft N905NA carries Discovery as it leaves Edwards AFB on its way to Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

-

One of the SCAs at its Dryden Flight Research Center home, with a very wet Rogers Dry Lake behind it.

-

Aft end of the SCA interior. A large stuffed spider is mounted on the aft pressure bulkhead.

-

The first class section in the nose of N905NA. This is the only area on the main deck that has not been stripped to the bare metal.

-

Atlantis on SCA N905NA returning to Kennedy Space Center in 1998.

-

SCA approaching Endeavour suspended in the Mate-Demate Device (MDD) in April 1994.

-

SCA mating with Endeavour in the Mate-Demate Device (MDD) in April 1994.

-

SCA ferry flights, 1992.

-

-

Enterprise separating from SCA N905NA.

-

Discovery transported to Washington, D.C. in April 2012 by SCA N905NA.

-

Enterprise being transported to New York City in April 2012 by SCA N905NA.

-

Planform view of SCA carrying Enterprise in April 2012.

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- ^ NASA - Dryden Flight Research Center (1977). "Shuttle Enterprise Free Flight". NASA. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ Jenkins 2000, pp. 36-38.

- ^ a b c Brack, Jon (2012-09-17). "Inside the Space Shuttle Carrier Aircraft". National Geographic. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 2000, pp. 38-39.

- ^ Felix Gilette (9 August 2005). "How Does the Space Shuttle Fly Home?". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Comparison of photos taken in 1982 and 1983 at Airliners.net

- ^ http://www.slate.com/id/2124238/

- ^ 2003 Edwards Air Force Base Air Show, see Shuttle Carrier images.

- ^ Shuttle Carrier Aircraft N911NA album on Photobucket

- ^ "Space Shuttle Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) Sites" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. December 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ Boeing Phantom Ray to catch shuttle ride at Lambert

- ^ "STS Chronology". NASA.

- ^ a b NASA's Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 911's Final Flight

- ^ Parabolic Arc, "Shuttle Carrier 747 to be Displayed in Palmdale", Douglas Messier, 2014-08-26

- ^ [1] A graphic history of 35 years of space shuttle ferry flights now adorns the upper forward fuselage of NASA Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 905. (NASA / Tony Landis)

- ^ Houston’s Shuttle Gets New Name, Familiar Ride

- ^ SpaceDaily, "Shuttle replica lifted and put on top of 747 carrier", Brooks Hays (UPI), 2014-08-14

- ^ Boeing 747-100 Technical Specifications, Boeing

Bibliography

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Boeing 747-100/200/300/SP (AirlinerTech Series, Vol. 6). Specialty Press, 2000. ISBN 1-58007-026-4.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System - The First 100 Missions, 3rd edition. Midland Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-9633974-5-1.