Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Mauch Chunk "The Switzerland of America" "The Gateway to the Poconos" | |

|---|---|

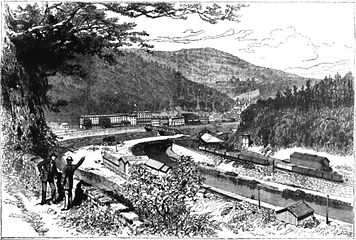

View of St. Marks from the Asa Packer Mansion grounds | |

Location of Jim Thorpe in Carbon County, Pennsylvania. | |

| Coordinates: 40°52′23″N 75°44′11″W / 40.87306°N 75.73639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Carbon |

| Founded | 1818 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Sofranko |

| Area | |

• Total | 14.92 sq mi (38.64 km2) |

| • Land | 14.60 sq mi (37.81 km2) |

| • Water | 0.32 sq mi (0.83 km2) |

| Elevation | 730 ft (220 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 4,781 |

• Estimate (2016)[3] | 4,607 |

| • Density | 315.59/sq mi (121.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 18229 |

| Area code | 570 Exchange: 325 |

| FIPS code | 42-025-38200 |

| FIPS code[4] | 42-38200 |

| GNIS ID[4][5][6] | 1178082, 1215045 |

| Website | www |

Jim Thorpe is a borough and the county seat of Carbon County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The population was 4,781 at the 2010 census.[7] The town has been called the "Switzerland of America" due to the picturesque scenery, mountainous location, and architecture; as well as the "Gateway to the Poconos." It is in eastern Pennsylvania about 80 miles (130 km) north of Philadelphia and 100 miles (160 km) west of New York City. This town is also historically known as the burial site for the body of Native American sports legend Jim Thorpe.

History

Jim Thorpe was founded as Mauch Chunk /ˌmɔːk ˈtʃʌŋk/, a name derived from the term Mawsch Unk (Bear Place) in the language of the native Munsee-Lenape Delaware peoples: possibly a reference to Bear Mountain, an extension of Mauch Chunk Ridge that resembled a sleeping bear, or perhaps the original profile of the ridge, which has since been changed heavily by 220 years of mining. The company town was founded by Josiah White and his two partners, founders of the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (LC&N). The town would be the lower terminus of a gravity railroad, the Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk Railroad, which would bring coal to the head of the Lehigh Canal for transshipment to the Delaware River, 43 kilometres (26.7 mi) downstream. It would thereby connect LC&N's coal mines to Philadelphia, Trenton, New York City, and other large cities in New Jersey and Delaware, and by ocean to the whole East Coast.

The town grew slowly in its first decade, then rapidly became larger as a railroad and coal-shipping center. (The other large city with coal mining was Scranton, with a population of over 140,000.) Mauch Chunk is on a flat at the mouth of a right bank tributary (facing downstream) of the Lehigh River at the foot of Mount Pisgah.

The left bank community East Mauch Chunk, which has more of the houses of modern Jim Thorpe, was settled later to support the short-lived Beaver Creek Railroad, the mines which spawned it, and the logging industry. It only came into its growth when the Lehigh Valley Railroad pushed up the valley to oppose LC&N's effective transportation monopoly over the region, which extended across to northwest Wilkes-Barre at Pittston on the Susquehanna River/Pennsylvania Canal. (See Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad, a subsidiary of LC&N.)

After the Pennsylvania Canal Commission smoothed the way, LC&N built the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad (L&S) from Pittston to Ashley, building the Ashley Planes inclined railway and linked that by rail from Mountain Top to White Haven at the head of the canal's upper works—referred to as the "Grand Lehigh Canal"—which navigations shortened the Lehigh Gorge (now located in the Lehigh Gorge State Park) route, cutting the distance from Philadelphia to Wilkes-Barre and the Wyoming Valley coal deposits by over 100 miles (160 km). This placed Mauch Chunk in the center of a nexus of transportation in country tough to travel through. When floods wiped out many of the upper Lehigh Canal works in 1861, the L&S Railroad was extended through the gap, and the so-called switchback-twisted backtrack through Avoca, with the improved engines of the day, enabled two-way steam locomotive traction and traffic despite the steep grades. The LC&N headquarters was built across the street from the stylish passenger station that was soon boarding passengers onto trains from New York and Philadelphia to Buffalo.

Mauch Chunk was the location of one of the trials of the Molly Maguires in 1876, which resulted in the hanging of four men found guilty of murder.[8] The population of the borough in 1900 was 4,020; in 1910, it was 3,952.[9]

Following the 1953 death of renowned athlete and Olympic medal winner Jim Thorpe, Thorpe's widow and third wife, Patricia, was angry when the government of Oklahoma would not erect a memorial to honor him.[10] When she heard that the boroughs of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk were desperately seeking to attract business, she made a deal with civic officials. According to Jim Thorpe's son, Jack, Patricia was motivated by money in seeking the deal.[11] The boroughs merged, renamed the new municipality in Jim Thorpe's honor,[when?] obtained the athlete's remains from his wife and erected a monument to the Oklahoma native, who began his sports career 100 miles (161 kilometres) southwest, as a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The monument site contains his tomb, two statues of him in athletic poses, and historical markers describing his life story. The grave rests on mounds of soil from Thorpe's native Oklahoma and from the Stockholm Olympic Stadium in which he won his Olympic medals.[12]

On June 24, 2010, one of Jim Thorpe's sons, Jack Thorpe, sued the town for his father's remains, citing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which is designed to return Native American artifacts to their tribal homelands.[13] On February 11, 2011, Judge Richard Caputo ruled that Jack Thorpe could not gain any monetary award, nor any amount for attorney's fees in the lawsuit and that for the lawsuit to continue other members of the Thorpe family and the Sac and Fox Nation would have to join him as plaintiffs. Before Jack Thorpe could respond to the ruling he died at the age of 73 on February 22, 2011. Because of his death his representatives were given more time to respond to the ruling. On May 2, 2011, William and Richard Thorpe, Jim Thorpe's remaining sons and the Sac & Fox Nation of Oklahoma joined the lawsuit, allowing it to continue.[14] On April 19, 2013, Federal Judge Richard Caputo ruled in favor of William and Richard Thorpe, ruling that the borough amounts to a museum under the law.[15] This ruling was reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit on October 23, 2014.[16] The US Supreme Court refused to hear their appeal on October 5, 2015 assuring that Jim Thorpe's remains will stay in Carbon County.[17]

The history of the borough is reflected in the architecture that makes up its many 19th century styles. A former resident and architectural historian, Hans Egli, noted the vast range of styles: Federalist, Greek Revival, Second Empire, Romanesque Revival, Queen Anne, and Richardsonian Romanesque. Most of these architectural examples remained intact beneath aluminum or vinyl siding that has since been removed.

Robert Venturi, a renowned Philadelphia architect, conducted a little-known planning study in the 1970s that attempted to understand the dynamics of historicism and tourism, notions that have come into their own in contemporary times. While Venturi's planning study was unique at the time, it has since become a critical factor in Jim Thorpe's rebound as a functioning and economically stable community.[18] Jim Thorpe tourism is based on its old architecture, and recreation such as hiking, paintball and white water rafting.

The Carbon County Section of the Lehigh Canal, Old Mauch Chunk Historic District, Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway, Asa Packer Mansion, Harry Packer Mansion, Carbon County Jail, Central Railroad of New Jersey Station, and St. Mark's Episcopal Church are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[19]

Mauch Chunk Switchback Gravity Railroad

In 1827, the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, a coal mining and shipping company with operations in Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, constructed an 8.7-mile (14.0 km) downhill track, known as a gravity railroad, to deliver coal (and a miner to operate the mine train's brake) to the Lehigh Canal in Mauch Chunk. This helped open up the area to commerce, and helped to fuel the Industrial Revolution in the United States. By the 1850s, the "Gravity Road" (as it became known) was providing rides to thrill seekers for 50 cents a ride (equal to $16.35 today). It is often cited as the first roller coaster in the United States. The Switchback Gravity Railroad Foundation was formed to study the feasibility of preserving and interpreting the remains of the Switchback Gravity Railroad on top of Mount Pisgah.[20]

Geography

Jim Thorpe is located near the center of Carbon County at 40°52′23″N 75°44′11″W / 40.87306°N 75.73639°W.[21]

In the deeps of the geologic timescale the two shorelines of the Lehigh River occupied by the 19th-century towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk were situated on the bottom of an ancient river-fed tarn, a mountain lake which filled the valley on the west bank and covered the relative flatlands on the east bank. The muddy bottom of that high tarn (the range then rivaling the Himalayas in size), where the waters pooled at a lower elevation amongst the twisted folds of four near-parallel ridgelines, created a level region whose settlements became the relatively flat lands on either bank of the Lehigh. The ridgelines, which run east-northeast to west-southwest, are (from north to south) Broad, Nesquehoning, Pisgah, and Mauch Chunk ridges (or Mountains)—each of which runs over 15 miles (24.1 km) west to the gaps cut by the Schuylkill River.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough of Jim Thorpe has a total area of 14.9 square miles (38.6 km2), of which 14.6 square miles (37.8 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.8 km2), or 2.15%, is water.[7] Jim Thorpe is 3 miles (5 km) north and upstream of Lehighton, below the Lehigh Gap which sunders Bear Mountain on the east bank from the extended ridge of Mauch Chunk Mountain. The town is 4 miles (6 km) east of Nesquehoning, which is up a steep grade and around the bend along U.S. 209 South, and also butting up against the slopes of Mount Pisgah. This was a key element in the LC&N's planning, for the grade from the mountain ridge down to the river enabled them to fill barges quickly, using chutes and an elevated entry from a road down the ridge face. Jim Thorpe's developed elevations range between the river slack water at 540 feet (160 m) above sea level—720 feet (219.5 m) to the town's upper streets, all below the western peak of Mount Pisgah, which tops out at 1,519 feet (463.0 m) above sea level.[5][6]

The elevation of the Borough of Jim Thorpe ranges from 540 feet (160 m) at Broadway and Hazard Square downtown to 1,700 feet (520 m) above sea level 3 miles (5 km) northeast of the borough center near the Penn Forest Township line.

Transportation

![]() US 209, although signed as a north-south route, tends to follow an east-west route in Pennsylvania. In Jim Thorpe and Lehighton, U.S. 209 runs in directions opposite its signage—i.e., northbound U.S. 209 runs southwards and vice versa.

US 209, although signed as a north-south route, tends to follow an east-west route in Pennsylvania. In Jim Thorpe and Lehighton, U.S. 209 runs in directions opposite its signage—i.e., northbound U.S. 209 runs southwards and vice versa.

- Intersects the Pennsylvania Turnpike Northeast Extension (Interstate 476) east of Lehighton, about 6 miles (10 km) southeast of Jim Thorpe.

- Intersects PA 309 at Tamaqua, about 14 miles (23 km) west of town.

- About 3 miles (5 km) west of town, intersects PA 93, a northwesterly route that intersects with Interstate 81 near Hazleton and with Interstate 80 in Sugarloaf Township.

![]() PA 903 has its southern terminus at U.S. 209 in Jim Thorpe. It is a north-south route that runs northeast of town.

PA 903 has its southern terminus at U.S. 209 in Jim Thorpe. It is a north-south route that runs northeast of town.

- Northern terminus 17 miles (27 km) northeast of town at PA 115 near the Pocono Raceway. (PA 115 intersects Interstate 80 about 2 miles (3 km) north of its junction with PA 903.)

- Intersects PA 534 in Penn Forest Township, about 13 miles (21 km) northeast of town.

- Has an E-Z-Pass-only interchange with Interstate 476 just north of the Hickory Run Service Plaza.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 5,945 | — | |

| 1970 | 5,456 | −8.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,263 | −3.5% | |

| 1990 | 5,048 | −4.1% | |

| 2000 | 4,804 | −4.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,781 | −0.5% | |

| 2016 (est.) | 4,607 | [3] | −3.6% |

| Sources:[22][23][24] | |||

As of the census[23] of 2010, there were 4,781 people, 2,290 households, and 1,468 families residing in the borough. The population density was 332.1 people per square mile (128.2/km²). There were 2,193 housing units at an average density of 151.6 per square mile (58.5/km²). The racial makeup of the borough was 98.36% White, 1.62% African American, 1.04% Native American, 1.27% Asian, 1.04% Pacific Islander, 1.04% from other races, and 1.62% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.83% of the population. A plurality of Jim Thorpe's residents are of Irish and Italian descent, typified by the connection to the Molly Maguires and the Italian immigrants who settled here in the 1800s. A large amount of Irish and Italian pride seen throughout the town (e.g. flags).

There were 1,967 households, of which 28.2% had children under the age of 18, 50.6% were married couples living together, 12.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.1% were non-families. 27.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the borough, the population was spread out, with 21.0% under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 28.8% from 25 to 44, 24.9% from 45 to 64, and 17.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.9 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $35,976, and the median income for a family was $43,710. Males had a median income of $31,141 versus $23,490 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $17,119. About 7.8% of families and 10.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.3% of those under age 18 and 6.8% of those age 65 or over.

Recreation

In a poll conducted in 2009 by Budget Travel magazine, Jim Thorpe was awarded a top 10 spot on America's Coolest Small Towns. The town registered 3,920 votes to land the #7 spot on the list. In 2012, Jim Thorpe was voted the fourth most beautiful small town in America in the Rand McNally/USA Today Road Rally series. Jim Thorpe is becoming a tourist destination, with many businesses catering to white water rafting, mountain biking, paintball and hiking. Trails in Lehigh Gorge State Park attract hikers from all over, with Glen Onoko Falls a top trail destination just north of downtown. Along with these sports, Jim Thorpe is popular among railroading fans and is known for its extraordinary architecture.

The town is home to the Asa Packer and Harry Packer mansions. Asa Packer founded Lehigh Valley Railroad and Lehigh University; Harry was his son. The mansions sit side by side on a hill overlooking downtown. The Asa Packer Mansion is a museum and has been conducting tours since Memorial Day of 1956. The Harry Packer Mansion is a bed and breakfast; it served as the model for the Haunted Mansion ride at Walt Disney World in Florida.[citation needed]

Jim Thorpe is home to the Anthracite Triathlon, an Olympic-distance triathlon open to amateur and professional triathletes. The swimming portion occurs in Mauch Chunk Lake. The bike course takes riders through the mining towns of Summit Hill, Nesquehoning, Lansford and Jim Thorpe. The running portion of the course is generally along the former alignment of a historic switchback railroad.[25]

The Anita Shapolsky Art Foundation was established at 20 West Broadway, in a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) 1859 former Presbyterian church, in Jim Thorpe in 1998.[26][27][28] There, through the non-profit 501(c)3 organization, Anita Shapolsky exhibits abstract artists and contemporary artworks during the summer, and provides educational programs for children.[26][27]

Gallery

-

Painting by Karl Bodmer (1839)

-

Historic buildings on Broadway

-

Lehigh Coal & Navigation Building, designed by architect Addison Hutton[29] Intersection of Broadway and Lehigh Avenue

-

Clock tower at the same intersection

-

Former Carbon County Jail, on Broadway

-

Mauch Chunk, depicted in an 1880 engraving

Education

Residents of Jim Thorpe may attend the local, public schools operated by Jim Thorpe Area School District which provides preschool and full day kindergarten through 12th grade. Both the Lawrence b. Morris Elementary School and Jim Thorpe Area High School are located in the borough of Jim Thorpe. In 2016, the Jim Thorpe Area School District's enrollment declined to 2,062 students.[30] In 2011, Jim Thorpe Area School District enrollment was 2,187 pupils.[31] The District's enrollment was 1,913 pupils in 2005-06.[32] Jim Thorpe Area School District operates three schools: Jim Thorpe Area High School (9th-12th), L.B Morris (Preschool, full-day kindergarten - 8th); Penn Kidder Campus (preschool - 8th). In 2016, Jim Thorpe Area School District’s graduation rate was just 88.76%. [33]

In 2016, the Pittsburgh Business Times ranked Jim Thorpe Area School District 272nd out of 493 public schools for academic achievement of its pupils.[34] In 2011 and 2012, Jim Thorpe Area School District achieved Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).[35]

High school aged students can attend the taxpayer funded Carbon Career & Technical Institute, located in Jim Thorpe, for training in the building trades, auto mechanics, culinary arts, allied health careers and other areas. Carbon Career & Technical Institute is funded by a consortium of the school districts, which includes: Jim Thorpe Area School District, Lehighton Area School District, Palmerton Area School District, Panther Valley School District and Weatherly Area School District.

Jim Thorpe Borough residents may also apply to attend any of the Commonwealth's 13 public cyber charter schools (in 2015) at no additional cost to the parents. The resident’s public school district is required to pay the charter school and cyber charter school tuition for residents who attend these public schools.[36][37] The tuition rate that Jim Thorpe Area School District must pay was 11,483.03 in 2015. By Commonwealth law, if the District provides transportation for its own students, then the District must provide transportation to any school that lies within 10 miles of its borders. Residents may also seek admission for their school aged child to any other public school district. When accepted for admission, the student's parents are responsible for paying an annual tuition fee set by the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Carbon-Lehigh Intermediate Unit #21 (located in Schnecksville, Lehigh County) provides a wide variety of services to children living in its region which includes Jim Thorpe. Early screening, special education services, speech and hearing therapy, autistic support, preschool classes and many other services like driver education are available. Services for children during the preschool years are provided without cost to their families when the child is determined to meet eligibility requirements. Intermediate units receive taxpayer funding: through subsidies paid by member school districts; through direct charges to users for some services; through the successful application for state and federal competitive grants and through private grants.[38]

- Libraries

Community members have access to the Carbon County public libraries. These libraries include: Penn-Kidder Library Center Inc. located in Albrightsville; Palmerton Area Library in Palmerton and Lehighton Area Memorial Library in Lehighton. Through these libraries, Pennsylvania residents have access to all POWER Library [2] online resources. By state law the school district is also required to open its libraries at least once a week to residents.[39][40]

See also

Other American cities with a personal name and surname as the municipal name:

- Albert Lea, Minnesota

- Carol Stream, Illinois

- George West, Texas

- Phil Campbell, Alabama

- Morgan Hill, California

References

- ^ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Aug 13, 2017.

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ a b

"FIPS55 Data: Pennsylvania". FIPS55 Data. United States Geological Survey. February 23, 2006. Archived from the original on June 18, 2006.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Jim Thorpe (populated place)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Borough of Jim Thorpe (civil)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Jim Thorpe borough, Pennsylvania". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ The Molly Maguires; Approaching Trial of the Murderers of John P. Jones --- Strong Array of Counsel for the Defense New York Times, 27 March 1876. Retrieved 2008-12-26

- ^ New International Encyclopedia

- ^ Hagerty, James R. (July 21, 2010). "Is There Life After Jim Thorpe for Jim Thorpe, Pa.?". The Wall Street Journal. p. A14.

- ^ "Frank Deford of Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel interviews Jack Thorpe". HBO (official channel on YouTube). Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ^ Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania – Jim Thorpe's Tourist Attraction Grave at Roadside America.

- ^ [1] Thorpe's son seeks return of remains, Associated Press, June 24, 2010

- ^ Zagofsky, Al (October 8, 2011). "Court decision on the athlete's remains may be forthcoming". Times News. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "Judge Sides With Sons About Legendary Athlete Jim Thorpe's Remains". Associated Press. April 19, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "Pennsylvania town named for Jim Thorpe can keep athlete's body". CBS News. October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court: Jim Thorpe's body to remain in town that bears his name". themorningcall.com. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Out of the Ordinary: Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Associates, Brownlee, David B. and Kathryn B. Hiesinger, published 2001, page 76

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ The switchback Gravity Railroad

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Anthracite Triathlon". Archived from the original on 2008-05-30. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ a b Magda Salvesen, Diane Cousineau (2005). Artists' Estates: Reputations in Trust. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813536049.

- ^ a b "Anita Shapolsky Gallery and AS Art Foundation". ArtSlant.

- ^ Victoria Donohoe (August 19, 1990). "Resourceful – Not 'Resort' – Art Found In Jim Thorpe, Pa". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ HAER

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (October 4, 2016). "District Fast Facts - Jim Thorpe Area School District".

- ^ NCES, Common Core of Data - Jim Thorpe Area School District, 2011

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education, Enrollment and Projections by LEA 2005-06 - 2020, July 2010

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (October 4, 2016). "Jim Thorpe Area High School Fast Facts 2016".

- ^ Pittsburgh Business Times, Guide to Pennsylvania Schools Statewide ranking 2016, April 5, 2016

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (September 21, 2012). "Jim Thorpe Area School District AYP Overview 2012".

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (2013). "Charter Schools".

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (2013). "What is a Charter School?".

- ^ Carbon-Lehigh Intermediate Unit 21 Administration, About the CLIU, 2016

- ^ PAschoollibraryproject.org, Creating 21st-Century Learners: A Report on Pennsylvania’s Public School Libraries, October 2012

- ^ Office of Commonwealth Libraries, Guidelines for Pennsylvania School Library Programs, 2011

![Lehigh Coal & Navigation Building, designed by architect Addison Hutton[29] Intersection of Broadway and Lehigh Avenue](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Jim_Thorpe_Lehigh_Broadway_2898px.jpg/360px-Jim_Thorpe_Lehigh_Broadway_2898px.jpg)