Compromise of 1850

- (Gold Rush) California applies to become a free state

- Texas claims territory as far as the Rio Grande

- New Mexico resists Texas, applies to become a free state.

- California is admitted as a free state

- Texas trades some territorial claims for debt relief

- New Mexico becomes New Mexico Territory with slavery undecided

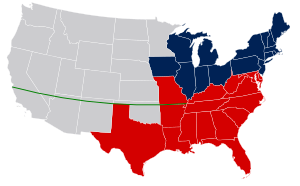

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850, which defused a four-year political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The compromise, drafted by Whig Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and brokered by Clay and Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, reduced sectional conflict. Controversy arose over the Fugitive Slave provision. The Compromise was greeted with relief, but each side disliked some of its specific provisions:

- Texas surrendered its claim to New Mexico as well as its claims north of 36°30'. It retained the Texas Panhandle, and the federal government took over the state's public debt.

- California was admitted as a free state, with its current boundaries.

- The South prevented adoption of the Wilmot Proviso that would have outlawed slavery in the new territories,[1] and the new Utah Territory and New Mexico Territory were allowed, under popular sovereignty, to decide whether to allow slavery in their borders. In practice, these lands were generally unsuited to plantation agriculture, and their settlers were uninterested in slavery.

- The slave trade, but not slavery altogether, was banned in the District of Columbia.

- A more stringent Fugitive Slave Law was enacted.

The Compromise became possible after the sudden death of President Zachary Taylor, who, although a slave owner, wanted to exclude slavery from the Southwest. Whig leader Henry Clay designed a compromise, which failed to pass in early 1850 because of opposition by both pro-slavery southern Democrats, led by John C. Calhoun, and anti-slavery northern Whigs. Upon Clay's instruction, Douglas then divided Clay's bill into several smaller pieces and narrowly won their passage, over the opposition of radicals on both sides.

Background

- Northwest Ordinance

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion

- Nullification crisis

- End of slavery in British colonies

- Texas Revolution

- United States v. Crandall

- Gag rule

- Commonwealth v. Aves

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

- American Slavery As It Is

- United States v. The Amistad

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- Texas annexation

- Mexican–American War

- Wilmot Proviso

- Nashville Convention

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Recapture of Anthony Burns

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Ostend Manifesto

- Bleeding Kansas

- Caning of Charles Sumner

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The Impending Crisis of the South

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Virginia v. John Brown

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise

- Secession of Southern states

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment

- Battle of Fort Sumter

Soon after the start of the Mexican War, when the extent of the contested territories was still unclear, the question of whether to allow slavery in those territories polarized the Northern and the Southern United States in the most bitter sectional conflict until then. A state the size of Texas attracted interest from both state residents and pro-slavery and anti-slavery camps on a national scale. Texas claimed land north of the 36°30' demarcation line for slavery, set by the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

The Texas Annexation resolution had required that if any new states were formed out of Texas' lands, those north of the Missouri Compromise line would become free states.[2]

According to historian Mark Stegmaier, "The Fugitive Slave Act, the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia, the admission of California as a free state, and even the application of the formula of popular sovereignty to the territories were all less important than the least remembered component of the Compromise of 1850—the statute by which Texas relinquished its claims to much of New Mexico in return for federal assumption of the debts."[3]

Stegmaier also refers to "the principal Southern demand for a division of California at the line of 35° north latitude" and says that "Southern extremists made clear that a congressionally mandated division of California figured uppermost on their agenda."[4]

During the deadlock of four years, the Second Party System broke up, Mormon pioneers settled Utah, the California Gold Rush settled northern California, and New Mexico under a federal military government turned back Texas's attempt to assert control over territory Texas claimed as far west as the Rio Grande. The eventual compromise preserved the Union but only for another decade.

Various proposals

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Proposals in 1846 to 1850 on the division of the Southwest included the following:

- The Wilmot Proviso banning slavery in any new territory to be acquired from Mexico, not including Texas, which had been annexed the previous year. It passed the House in August 1846 and February 1847 but not the Senate. Later, an effort failed to attach the proviso to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

- The Extension of the Missouri Compromise line was proposed by failed amendments to the Wilmot Proviso by William W. Wick and then Stephen Douglas to extend the Missouri Compromise line (36°30' parallel north) west to the Pacific (south of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California) to allow the possibility of slavery in most of present-day New Mexico and Arizona, and Southern California. That line was again proposed by the Nashville Convention of June 1850.

- Popular sovereignty, developed by Lewis Cass and Douglas as the position of the Democratic Party position, was to let each territory decide itself whether to allow slavery.

- William L. Yancey's "Alabama Platform," endorsed by the Alabama and the Georgia legislatures and by Democratic state conventions in Florida and Virginia, called for no restrictions on slavery in the territories by the federal government or territorial governments before statehood, opposition to any candidates supporting either the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty, and federal legislation to overrule Mexican anti-slavery laws.

- Two free states were proposed by Zachary Taylor, who served as President from March 1849 to July 1850. As President, he proposed that the entire area become two free states, called California and New Mexico but much larger than the ones today. None of the area would be left as an unorganized or organized territory, which would avoid the question of slavery in the territories.

- Changing Texas's borders was proposed by Senator Thomas Hart Benton in December 1849 or January 1850. Texas's western and northern boundaries would be the 102nd meridian west and the 34th parallel north.

- Two southern states were proposed by Senator John Bell, with the assent of Texas) in February 1850. New Mexico would get all Texas land north of the 34th parallel north, including today's Texas Panhandle, and the area to the south, including the southeastern part of today's New Mexico, would be divided at the Colorado River of Texas into two Southern states, balancing the admission of California and New Mexico as free states.[5]

- The first draft of the compromise of 1850 had Texas's northwestern boundary be a straight, diagonal line from the Rio Grande 20 miles north of El Paso to the Red River (Mississippi watershed) at the 100th meridian west, the southwestern corner of today's Oklahoma.

Final proposed compromise

Henry Clay takes the floor of the Old Senate Chamber; Vice President Millard Fillmore presides as John C. Calhoun (to the right of the Speaker's chair) and Daniel Webster (seated to the left of Clay) look on.

On January 29, 1850, Whig Senator Henry Clay gave a speech for compromise on the issues dividing the Union. However, Clay's specific proposals for achieving a compromise, including his idea for Texas' boundary, were not adopted in a single bill.[6] Upon Clay's urging, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Democrat of Illinois, divided Clay's bill into several smaller bills and passed each separately. When he instructed Douglas, Clay was nearly dead and unable to guide the congressional debate any further. The Compromise came to coalesce around a plan dividing Texas at its present-day boundaries, creating territorial governments with "popular sovereignty," without the Wilmot Proviso, for New Mexico and Utah, admitting California as a free state, abolishing the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and enacting a new fugitive slave law.

The Compromise of 1850 was formally proposed by Clay and guided to passage by Douglas over Northern Whig and Southern Democrat opposition. It was enacted September 1850 with the following terms:

- California admitted as a free state.

- Utah Territory and New Mexico Territory organized with slavery to be decided by popular sovereignty.

- Texas dropped its claim to land north of the 32nd parallel north and west of the 103rd meridian west in favor of New Mexico Territory, and north of the 36°30' parallel north and east of the 103rd meridian west which became unorganized territory. Texas's boundaries were set at their present form. Senator James Pearce of Maryland drafted the final proposal[7] in which Texas ceded its claims to land which later became half of present-day New Mexico, a third of Colorado, and small portions of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming to the federal government, in return for the assumption of $10 million of the old republic's debt.[8][9] El Paso, where Texas had established county government, was left in Texas.

- Slave trade was abolished in the District of Columbia but not slavery itself.

- The Fugitive Slave Act was strengthened.

Division of Whigs

Most Northern Whigs, led by William Henry Seward, who delivered his famous "Higher Law" speech during the controversy, opposed the Compromise as well because it would apply the Wilmot Proviso to the western territories and because of the pressing of ordinary citizens into duty on slave-hunting patrols. That provision was inserted by Democratic Virginia Senator James M. Mason to entice border-state Whigs, who faced the greatest danger of losing slaves as fugitives but were lukewarm on general sectional issues related to the South on Texas's land claims.[10]

Zachary Taylor avoided the issue as the Whig candidate during the 1848 US presidential election but then as President, he attempted to sidestep the entire controversy by pushing to admit California and New Mexico as free states immediately to avoid the entire territorial process and the Wilmot Proviso question. Taylor was one of the few Southerners to support that idea.[11]

Northern Democrats and Southern Whigs supported the Compromise. Southern Whigs, many of whom were from the border states, supported the stronger fugitive slave law.

Debate and results

On April 17, a "Committee of Thirteen" agreed on the border of Texas as part of Clay's plan. The dimensions were later changed. That same day, during debates on the measures in the Senate, Vice President Fillmore and Senator Benton verbally sparred, with Fillmore charging that the Missourian was "out of order," During the heated debates, Compromise floor leader Henry S. Foote of Mississippi drew a pistol on Benton.

In early June, nine slaveholding Southern states sent delegates to the Nashville Convention to determine their course of action if the compromise passed. While some delegates preached secession, the moderates ruled and proposed a series of compromises, including extending the dividing line designated by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 to the Pacific Coast.

The various bills were initially combined into one "omnibus" bill. Despite Clay's efforts, it failed in a crucial vote on July 31, opposed by southern Democrats and by northern Whigs. He announced on the Senate floor the next day that he intended to pass each individual part of the bill. The 73-year-old Clay, however, was physically exhausted from the effects of tuberculosis, which would eventually kill him, began to take their toll. Clay left the Senate to recuperate in Newport, Rhode Island, and Stephen A. Douglas wrote the separate bills and guided them through the Senate.[12]

The situation had been changed by the sudden death of Taylor and the accession of Vice President Millard Fillmore to the presidency, on July 9, 1850. Fillmore, anxious to find a quick solution to the conflict in Texas over the border with New Mexico, which threatened to become armed conflict between Texas militia and the federal soldiers, reversed the administration's position late in July and threw its support to the compromise measures.[13] The Northern Democrats held together and supported each of the bills and gained enough Whigs or Southern Democrats to pass all of them. They were signed by Fillmore between September 9 and September 20, 1850.

- California was admitted as a free state. It passed the House 150–56.[14][15] It passed the Senate 34–18.[16]

- The slave trade was abolished (the sale of slaves, not the institution of slavery) in the District of Columbia.

- The Territory of Utah was organized under the rule of popular sovereignty. It passed the House 97–85.[17]

- The Territory of New Mexico was organized under the rule of popular sovereignty. It passed the House 108–97.[18] It passed the Senate 30–20.[19]

- A harsher Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the Senate 27–12,[20] and by the House 109–76.[21]

- Texas gave up much of the western land it claimed and received compensation of $10,000,000 to pay off its national debt.

Clay was still given much of the credit for success. It quieted the controversy between Northerners and Southerners over the expansion of slavery and delayed secession and civil war for another decade. Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi, who had suggested the creation of the Committee of Thirteen, later said, "Had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860–'61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war."[22]

Implications

The Compromise proved widely popular politically, and both parties committed themselves in their platforms to the finality of the Compromise on sectional issues. The strongest opposition in the South occurred in the states of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, but Unionists soon prevailed, spearheaded by Georgians Alexander Stephens, Robert Toombs, and Howell Cobb and the creation of the Georgia Platform. The peace was broken only by the divisive Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 introduced by Stephen Douglas, which had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise and led directly to the formation of the Republican Party, whose capture of the national government in 1860 led directly to the secession crisis of 1860–1861.

Many historians argue that the Compromise played a major role in postponing the American Civil War for a decade, while the Northwest was growing more wealthy and more populous and was being brought into closer relations with the Northeast.[23] During that decade, the Whig Party had completely broken down, to be replaced with the new Republican Party dominant in the North and the Democrats in the South.[24] Others argue that the Compromise only made more obvious the pre-existing sectional divisions and laid the groundwork for future conflict. They view the Fugitive Slave Law ad helping to polarize the US, as shown in the enormous reaction to Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law aroused feelings of bitterness in the North. Furthermore, the Compromise of 1850 led to a breakdown in the spirit of compromise in the United States in the antebellum period, directly before the Civil War. The Compromise exemplifies that spirit, but the deaths of influential senators who worked on the compromise, primarily Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, contributed to the feeling of increasing disparity between the North and South.

The delay of hostilities for ten years allowed the free economy of the northern states to continue to industrialize. The southern states, largely based on slave labor and cash crop production, lacked the ability to industrialize heavily.[25] By 1860, the northern states had added many more miles of railroad, steel production, modern factories, and population to the advantages already possessed in 1850. The North was better able to supply, equip, and man its armed forces, which would prove decisive in the later stages of the war.

Issues

Three major types of issues were addressed by the Compromise of 1850: a variety of boundary issues, the status of territory issues, and the issue of slavery. While capable of analytical distinction, the boundary and territory issues were actually included in the overarching issue of slavery. Pro-slavery and anti-slavery interests were each concerned with both the amount of land on which slavery was permitted and with the number of States in the slave or free camps. Since Texas was a slave state, not only the residents of that state but also both camps on a national scale had an interest in the size of Texas.

The general solution that was adopted by the Compromise of 1850 was to transfer a considerable part of the territory claimed by the state to the federal government; to organize two new territories formally, the Territory of New Mexico and the Territory of Utah, which expressly would be allowed to locally determine whether they would become slave or free territories( to add another free state to the Union (California), to adopt a severe measure to recover slaves who had escaped to a free state or free territory (the Fugitive Slave Law); and to abolish the slave trade in the District of Columbia.

Texas

The independent Republic of Texas won the decisive Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836) against Mexico and captured Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. He signed the Treaties of Velasco, which recognized the Rio Grande as the boundary of the Republic of Texas. The treaties were then repudiated by the government of Mexico, which insisted that it was sovereign over Texas and promised to reclaim the lost territories. To the extent that there was a de facto recognition, Mexico treated the Nueces River as its northern boundary control. A huge, largely-unsettled area was between the two rivers. Neither Mexico nor the Republic of Texas had the military strength to assert its territorial claim. On December 29, 1845, the Republic of Texas was annexed to the United States and became the 28th state. Texas was staunchly committed to slavery, with its constitution making illegal for the legislature to free slaves. With the annexation, the United States inherited the territorial claims of the former Republic of Texas against Mexico. The territorial claim to the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande and Mexican resistance to it both led to the Mexican–American War. On February 2, 1848, the war was concluded by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Among its provisos was the recognition by Mexico of the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande as part of the United States.

The Republic of Texas had claimed ownership of the eastern half of present-day New Mexico, along with sections of Colorado, Kansas and Wyoming, but Texas had never effectively controlled the area, which was dominated by hostile Indian tribes (see Comancheria). However, the federal government now controlled the area after 1846. The Compromise of 1850 solved the problem by setting the present boundaries of Texas, in return for $10 million in federal bonds paid to the State of Texas.[26]

The state was heavily burdened with debt, which had been contracted during its struggles as the Republic of Texas. The federal government agreed to pay $10 million of bonds in return for the transfer of a large portion of the claimed area of the state to the territory of the federal government and for the relinquishment of various claims of Texas had on the federal government. (The bonds bore interest at the rate of 5%, which interest was collectible by Texas every six months, and the principal was redeemable at the end of fourteen years.)[27]

The Constitution (Article IV, Section 3) does not permit Congress unilaterally to reduce the territory of any state so the first part of the Compromise of 1850 had to take the form of an offer to the Texas State Legislature, rather than a unilateral enactment, which ratified the bargain and, in due course, the transfer of a large swath of land from the state of Texas to the federal government was accomplished.

Texas was allowed to keep the following portions of the disputed land: south of the 32nd parallel and south of the 36°30' parallel north and east of the 103rd meridian west. The rest of the disputed land was transferred to the Federal Government.

New Mexico and Utah Territories

The first law of the Compromise of 1850 also organized the Territory of New Mexico. The second law, also enacted September 9, 1850, organized the Territory of Utah.

Some of the land had been claimed by the Republic of Texas. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo made no mention of the claims of the Republic of Texas; Mexico simply agreed to a Mexico-U.S. border south of both the "Mexican Cession" and the Republic of Texas claims.[28] Before the Compromise of 1850, the disputed land had been claimed but never controlled by the state of Texas. Of importance in 1850 was land included in present-day eastern New Mexico.

From the Mexican Cession, the New Mexico Territory received most of the present-day state of Arizona, most of the western part of the present-day state of New Mexico, and the southern tip of present-day Nevada (south of the 37th parallel). From Texas, the territory received most of present-day eastern New Mexico, a portion of present-day Colorado (east of the crest of the Rocky Mountains, west of the 103rd meridian, and south of the 38th parallel).

From the Mexican Cession, the Utah Territory received present-day Utah, most of present-day Nevada (everything north of the 37th parallel), a major part of present-day Colorado (everything west of the crest of the Rocky Mountains), and a small part of present-day Wyoming. That included the newly founded colony at Salt Lake, of Brigham Young. From Texas, the Utah Territory received most of present-day eastern New Mexico and some of present-day Colorado that is east of the crest of the Rocky Mountains.

A key provision of each of the laws respectively organizing the Territory of New Mexico and the Territory of Utah was that slavery would be decuded by local option, called popular sovereignty. That was an important repudiation of the idea behind the failed to prohibit slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico.

California

California was part the Mexican Cession. After the Mexican War, California was essentially run by military governors. President James K. Polk tried to get Congress to establish a territorial government in California officially, but the increasingly-sectional debates prevented that.[29] The South wanted to extend slave territory to Southern California and to the Pacific Coast, but the North did not.

From late 1848, Americans and foreigners of many different countries rushed into California for the California Gold Rush, exponentially increasing the population. In response to growing demand for a better more representative government, a Constitutional Convention was held in 1849. The delegates unanimously outlawed slavery. They had no interest in extending the Missouri Compromise Line through California and splitting the state; the lightly-populated southern half never had slavery and was heavily Hispanic.[30]

The third statute of the Compromise of 1850 allowed California to be admitted to the Union, undivided, as a free state on September 9, 1850.[31]

Fugitive Slave Law

The fourth statute of the Compromise of 1850, enacted September 18, 1850, is informally known as the Fugitive Slave Law, or the Fugitive Slave Act. It bolstered the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. The new version of the Fugitive Slave Law required federal judicial officials in all states and federal territories, including in those states and territories in which slavery was prohibited, to assist with the return of escaped slaves to their masters actively in the states and territories permitting slavery. Any federal marshal or other official who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave was liable to a fine of $1000. Law enforcement everywhere in the US had a duty to arrest anyone suspected of being a fugitive slave on no more evidence than a claimant's sworn testimony of ownership. Suspected slaves could neither ask for a jury trial nor testify on their own behalf. In addition, any person aiding a runaway slave by providing food or shelter was to be subject to six months' imprisonment and a $1000 fine. Officers capturing a fugitive slave were entitled to a fee for their work.

In addition to federal officials, the ordinary citizens of free states could be summoned to join a posse and be required to assist in the capture, custody, and/or transportation of the alleged escaped slave.

The law was so rigorously pro-slavery as to prohibit the admission of the testimony of a person accused of being an escaped slave into evidence at the judicial hearing to determine the status of the accused escaped slave. Thus, iffreedmen were claimed to be an escaped slave, they could not resist their return to slavery by truthfully telling their own actual history.

The Fugitive Slave Act was essential to meet Southern demands. In terms of public opinion in the North, the critical provision was that ordinary citizens were required to aid slave catchers. Many northerners deeply resented that requirement to help slavery personally. Resentment towards the Act continued to heighten tensions between the North and South, which were inflamed further by abolitionists such as Harriet Beecher Stowe. Her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin, stressed the horrors of recapturing escaped slaves and outraged Southerners.[32]

End of slave trade in District of Columbia

The fifth law, enacted on September 20, 1850, prohibited the slave trade but allowed slavery itself in the District of Columbia.[33] Southerners in Congress were unanimous in opposing that provision, which was seen as a concession to the abolitionists, but they were outvoted.[34]

See also

- Uncle Tom's Cabin – a reaction against the Fugitive Slave Law

- Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which reopened the slavery issue

References

- ^ Michael Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (2003) p. 252

- ^ Joint Resolution of Congress, Mar. 1, 1845

- ^ Mark J. Stegmaier (1996). Texas, New Mexico, and the compromise of 1850: boundary dispute & sectional conflict. Kent State University Press.

- ^ Stegmaier, p. 172 and p. 177

- ^ W. J. Spillman (January 1904). "ADJUSTMENT OF THE TEXAS BOUNDARY IN 1850". Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association. Vol. 7.

- ^ Remini, Robert. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (1993) pp 730–61

- ^ Texas State Historical Association. "COMPROMISE OF 1850". The Handbook of Texas.

- ^ Compromise of 1850 from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ^ Cotton Culture from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ^ John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln's right hand (1996) p. 85

- ^ Elbert B. Smith, President Zachary Taylor: the hero president (2007) p. 238

- ^ Eaton (1957) pp. 192–193. Remini (1991) pp. 756–759

- ^ Michael Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (1999), pp. 529–530: "only rapid passage of the omnibus bill appeared to offer a timely escape from the crisis."

- ^ "TO PASS S. 169. (P.1772-1)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Holman Hamilton, Prologue to Conflict (University of Kentucky Press, 1965), p. 160

- ^ "ON PASSAGE S. 169". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "TO PASS S. 225 (9 STAT. 453, APP. 9/9/1850), AN ACT TO ESTABLISH A TERRITORIAL GOVERNMENT FOR UTAH. (P.1776-1)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "TO PASS S. 307. (P.1764-3)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "ON PASSAGE OF THE BILL S. 307. (P. 1555-3)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "ON ORDERING ENGROSSMENT AND 3RD READING OF THE BILL S. 23. (P. 1630-2)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ "TO PASS S. 23. (P.1817-1)". GovTrack.us. 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Remini (1991) pp. 761–62

- ^ Robert Remini,The House: A History of the House of Representatives (2006) p. 147

- ^ Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s (1978).

- ^ Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Fruits of Merchant Capital (1983).

- ^ Mark J. Stegmaier, Texas, New Mexico, and the Compromise of 1850: Boundary Dispute and Sectional Crisis (1998)

- ^ Hamilton, Holman (1957). "Texas Bonds and Northern Profits: A Study in Compromise, Investment, and Lobby Influence". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 43 (4). Organization of American Historians: 579–94. doi:10.2307/1902274. ISSN 0161-391X. JSTOR 1902274 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Handbook of Texas Online: Compromise of 1850". Tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ California and New Mexico: Message from the President of the United States. By United States. President (1849–1850 : Taylor), United States. War Dept (Ex. Doc 17 page 1) Google eBook

- ^ William Henry Ellison. A self-governing dominion, California, 1849–1860 (1950) online

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Larry Gara, "The Fugitive Slave Law: A Double Paradox," Civil War History, September 1964, vol. 10#3, pp. 229–240

- ^ David L. Lewis, District of Columbia: A Bicentennial History, (W.W. Norton, 1976), 54-56.

- ^ Damani Davis, "Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation'S Capital," Prologue, Spring 2010, vol. 42#1, pp. 52–59

Sources

- Bell, John Frederick. "Poetry's Place in the Crisis and Compromise of 1850." Journal of the Civil War Era 5#3 (2015): 399–421.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. America's Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise That Preserved the Union (2012) excerpt and text search

- Foster, Herbert D. (1922). "Webster's Seventh of March Speech and the Secession Movement, 1850". American Historical Review. 27 (2): 245–270. doi:10.2307/1836156.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. Henry Clay: The Essential American (2010), major scholarly biography; 624 pp.

- Hamilton, Holman. Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850 (1964), the standard historical study

- Hamilton, Holman (1954). "Democratic Senate Leadership and the Compromise of 1850". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 41 (3): 403–18. doi:10.2307/1897490. ISSN 0161-391X. JSTOR 1897490.

- Holman Hamilton. Zachary Taylor, Soldier in the White House (1951).

- Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s (1978).

- Holt, Michael F. The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War (2005).

- Johannsen, Robert W. Stephen A. Douglas (1973) (ISBN 0195016203)

- William Aloysius Keleher (1951). Turmoil in New Mexico. Santa Fe: Rydal Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0632-6.

- Knupfer, Peter B. "Compromise and Statesmanship: Henry Clay's Union." in Knupfer, The Union As It Is: Constitutional Unionism and Sectional Compromise, 1787–1861 (1991), pp. 119–57.

- Morrison, Michael A. Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War (1997) (ISBN 0807823198)

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union (1947) v 2, highly detailed narrative

- Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861 (1977), pp 90–120; Pulitzer Prize

- Remini, Robert. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (1991)

- Remini, Robert. At the Edge of the Precipice: Henry Clay and the Compromise That Saved the Union (2010) 184 pages; the Compromise of 1850

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, vol. i. (1896). complegte text online

- Rozwenc, Edwin C. ed. The Compromise of 1850. (1957) convenient collection of primary and secondary documents; 102 pp.

- Russel, Robert R. (1956). "What Was the Compromise of 1850?". The Journal of Southern History. 22 (3). Southern Historical Association: 292–309. doi:10.2307/2954547. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2954547 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Sewell, Richard H. Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States 1837–1860 New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Stegmaier, Mark J. (1996). Texas, New Mexico, and the Compromise of 1850: Boundary Dispute & Sectional Crisis. Kent State University Press.

- Wiltse, Charles M. John C. Calhoun, Sectionalist, 1840–1850 (1951)

External links

- 31st United States Congress

- 1850 in American politics

- 1850 in California

- 1850 in New Mexico Territory

- 1850 in Texas

- 1850 in Utah Territory

- 1850 in the United States

- 1850 in law

- History of the United States (1849–65)

- History of United States expansionism

- Presidency of Millard Fillmore

- Pre-statehood history of California

- New Mexico Territory

- Slavery in the United States

- United States federal territory and statehood legislation

- Utah Territory

- September 1850 events