Ankylosaurus

| Ankylosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of Ankylosaurus skull (AMNH 5214) in front view, Museum of the Rockies | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Ankylosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Ankylosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Ankylosaurini |

| Genus: | †Ankylosaurus Brown, 1908 |

| Species: | †A. magniventris

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown, 1908

| |

Ankylosaurus (/ˌæŋkəloʊˈsɔːrəs/ ANG-kə-lo-SAWR-əs[1]) is a genus of armored dinosaur. Fossils of Ankylosaurus have been found in geological formations dating to the very end of the Cretaceous Period, between about 68–66 million years ago, in western North America, making it among the last of the non-avian dinosaurs. It was named by Barnum Brown in 1908, and the only species classified in the genus is A. magniventris. The genus name means "fused lizard" and the specific name means "great belly". A handful of specimens have been excavated to date, but a complete skeleton has not been discovered. Though other members of Ankylosauria are represented by more extensive fossil material, Ankylosaurus is often considered the archetypal member of its group.

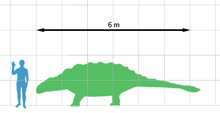

The largest known ankylosaurid, Ankylosaurus measured up to 6.25 m (20.5 feet) in length, 1.7 m (5.6 feet) in height, and weighed about 4.8–6 tonnes (11,000–13,000 lb). It was a quadrupedal animal, with a broad, robust body. It had a wide, low skull, with two horns pointing backwards from the back of the head, and two horns below these that pointed backwards and down. The front part of the jaws were covered in a beak, with rows of small, leaf-shaped teeth further behind it. It was covered in armor plates, or osteoderms, with bony half-rings covering the neck, and had a large club on the end of its tail. Bones in the skull and other parts of the body were fused, increasing their strength, and this feature is the source of the genus name.

Ankylosaurus is a member of the family Ankylosauridae, and its closest relatives appear to be Anodontosaurus and Euoplocephalus. Ankylosaurus is thought to have been a slow moving animal, able to make quick movements when necessary. Its broad muzzle indicates it was a non-selective browser. Sinuses and nasal chambers in the snout may have been for heat and water balance or played a role in vocalization. The tail club is thought to have been used in defense against predators or in intraspecific combat. Ankylosaurus has been found in the Hell Creek, Lance, and Scollard formations, but appears to have been rare in its environment. Although it lived alongside a nodosaurid ankylosaur, their ranges and ecological niches do not appear to have overlapped, and Ankylosaurus may have inhabited upland areas. Ankylosaurus also lived alongside dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and Edmontosaurus.

Description

Ankylosaurus is the largest known ankylosaurid dinosaur, estimated to have been up to 6.25 m (20.5 feet) long, 1.5 m (4.9 feet) wide, and 1.7 m (5.6 feet) tall at the hip. This length has been proposed by American palaeontologist Kenneth Carpenter, and is based on the largest known skull (specimen NMC 8880), which is 64.5 cm (25.4 inches) long and 74.5 cm (29.3 inches) wide. The smallest known skull (specimen AMNH 5214) is 55.5 cm (21.9 inches) long and 64.5 cm (25.4 inches) wide, and this specimen is estimated to have been 5.4 m (17.7 feet) long and around 1.4 m (4.6 feet) tall.[2] Other authors have proposed a body length of 7 m (23 feet),[3] 8–9 m (26.2–29.5 ft),[4] or more than 9 m (29.5 feet).[5] The weight of the animal has been estimated at 4.8–6 tonnes (11,000–13,000 lb).[6][3][7]

The structure of much of the skeleton of Ankylosaurus, including most of the pelvis, tail and feet, is still unknown.[2] It was quadrupedal, and its hind limbs were longer than the forelimbs.[7] The scapula (shoulder blade) and coracoid (a rectangular bone connected to the lower end of the scapula) of specimen AMNH 5895 were fused, and had entheses (connective tissue) for various muscle attachments. The scapula was 61.5 cm (24.2 inches) long. The humerus (upper arm bone) was short and very broad, and about 54 cm (21 inches) long in specimen AMNH 5214. The femur (thigh bone) was very robust, and 67 cm (26 inches) long in AMNH 5214. While the feet of Ankylosaurus are incompletely known, the hindfeet probably had three toes, as is the case in related animals.[2]

The cervical vertebrae of the neck had broad neural spines that increased in height towards the body. The front part of the neural spines had well developed entheses, which was common among adult dinosaurs, and indicates the presence of large ligaments which helped support the massive head. The dorsal vertebrae of the back had centra (or bodies) that were short relative to their width, and their neural spines were short and narrow. The dorsal vertebrae were tightly spaced, which limited the downwards movement of the back. The neural spines had ossified (turned to bone) tendons, which also overlapped some of the vertebrae. The ribs of the last four back vertebrae were fused to them, and the ribcage was very broad in this part of the body. The ribs had scars that show where muscles attached to them. The caudal vertebrae of the tail had centra that were slightly amphicoelous, meaning they were concave on both sides. The interlocked zygapophyses (articular processes) of the caudal vertebrae formed a V-shape when seen from above.[2]

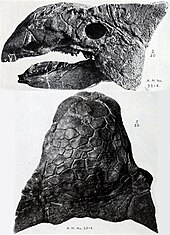

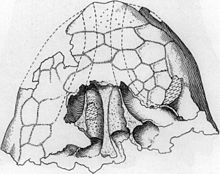

Skull

The three known Ankylosaurus skulls differ in various details, but this is thought to be the result of taphonomy (changes happening during fossilization of the remains) and individual variation. The skull was low and triangular in shape, wider than it was long. It had a broad beak on the premaxillae. The orbits (eye sockets) were almost round to slightly oval and did not face directly sideways, because the skull tapered towards the front. Crests above the orbits merged into the upper squamosal horns (their shape has been described as "pyramidal"), which pointed backwards to the sides from the back of the skull. The crest and horn were probably separate elements originally, as seen in the related Pinacosaurus and Euoplocephalus. Below the upper horns, jugal horns were present, which pointed backwards and down. The horns may have originally been osteoderms (armor plates) that fused to the skull. However, the scale pattern on the skull surface was instead the result of remodelling of the skull. This obliterated the sutures between skull elements, which is common for adult ankylosaurs. The scale pattern of the skull was variable between specimens, though some details are shared; it had a diamond-shaped scale (internarial scale) at the font of the snout, two squamosal osteoderms above the orbit, and a ridge of scales at the back of the skull.[2][8]

The snout of Ankylosaurus was arched and truncated at the front, and the nostrils were ellipse-shaped and faced sideways, unlike in many other ankylosaurids where they faced the front or upwards. This was because the sinuses were expanded to the sides of the premaxilla bone, to a larger extent than seen in other ankylosaurs. The nostrils also had an intranarial septum, which separated the nasal passage from the sinus. Each side of the snout had five sinuses, four of which expanded in to the maxilla bone. The nasal cavities or chambers of Ankylosaurus were elongated and separated by a septum at the midline, which divided the inside of the snout in two mirrored halves. The septum had two openings, including the choanae (internal nostrils).[2]

The maxillae expanded to the sides, giving the impression of a bulge, which may have been due to the sinuses inside. The maxillae had a ridge which may have been the attachment site for fleshy cheeks; the presence of cheeks in ornithischians is controversial, but some nodosaurid ankylosaurs had armor plates that covered the cheek region, which may have been embedded in the flesh. Specimen AMNH 5214 has 34-35 dental alveoli (tooth sockets) in the maxilla, which was more teeth than any other ankylosaurid. The tooth rows in the maxillae of this specimen are about 20 cm (8 inches) long. Each aveoli had a foramen (opening) near its side wherein a replacement tooth could be seen. The back of the skull was broad and low.[2]

Compared to other ankylosaurs, the mandible of Ankylosaurus was low in proportion to its length, and the tooth row was almost straight instead of arched, when seen from the side. The mandibles are only completely preserved in the smallest specimen (AMNH 5214) and are about 41 cm (16 inches) long. The incomplete mandible of the largest specimen (NMC 8880) is the same length. AMNH 5214 has 35 dental alveoli in the left dentary and 36 in the right. The predentary bone of the tip of the mandibles has not yet been found.[2] Like other ankylosaurs, Ankylosaurus had small, phylliform (leaf-shaped) teeth, which were compressed sideways.[9] The teeth were mostly taller than they were wide, and were very small in relation to the size of the skull. Some teeth from behind in the tooth row curved backwards, and tooth crowns were usually flatter on one side than the other.[2] Ankylosaurus teeth are diagnostic and can be distinguished from the teeth of other ankylosaurids based on their smooth sides. The denticles were large, their number ranging from six to eight on the front part of the tooth, and five to seven behind.[2][10]

Armor

A prominent feature of Ankylosaurus was its armor, consisting of knobs and plates of bone known as osteoderms or scutes embedded in the skin. These have not been found in articulation, so their exact placement on the body is unknown, though inferences can be made based on related animals. The osteoderms ranged from 1 cm (0.4 inches) in diameter to 35.5 cm (14.0 inches) in length, and also varied in shape. The osteoderms of Ankylosaurus were generally thin walled and hollowed on the underside. Compared to Euoplocephalus, the osteoderms of Ankylosaurus were smoother in texture. The osteoderms covering the body were very flat, though with a low keel at one margin. In contrast, the nodosaurid Edmontonia had high keels, stretching from one margin to the other on the midline of its osteoderms. Ankylosaurus had some smaller osteoderms with a keel across the midline. Some osteoderms without keels may have been placed above the hip region, as in Euoplocephalus. Flattened, pointed plates resemble those on the sides of the tail of Saichania. Osteoderms with oval keels could have been placed on the upper side of the tail or the side of the limbs. Small osteoderms and ossicles likely occupied the space between the larger ones.[2]

Like other ankylosaurids, Ankylosaurus had cervical half-rings (armor plates on the neck), but these are only known from fragments, making their exact arrangement uncertain. Carpenter suggested that when seen from above, the plates would have been paired, and created an inverted V-shape across the neck, with the midline gap probably being filled with small ossicles (round bony scutes) to allow for movement. He believed the width of this armor belt was too wide to have fitted solely on the neck, and that it covered the base of the neck and continued onto the shoulder region. Paleontologists Victoria M. Arbour and Philip J. Currie disagreed with Carpenter's interpretation, and pointed out that the cervical half-ring fragments of specimen AMNH 5895 did not fit together in the way proposed by Carpenter (though this could be due to breakage). They instead suggested that the fragments represented the remains of two cervical half-rings, which formed two semi-circular plates of armor around the upper part of the neck, as in the closely related Anodontosaurus and Euoplocephalus.[2][8]

The tail club of Ankylosaurus was composed of two large osteoderms, with a row of small osteoderms at the midline, and two small osteoderms at the tip. As only the tail club of specimen AMNH 5214 is known, the range of variation between individuals is unknown. The tail club of AMNH 5214 is 450 mm (18 in) wide. The last seven tail vertebrae formed the "handle" of the tail club. These vertebrae were in contact, with no cartilage between them, and sometimes co-ossified, which made them immobile. Ossified tendons attached to the vertebrae in front of the tail club, and these features together helped strengthen it.[2][11]

History of discovery

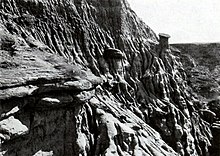

In 1906, an American Museum of Natural History expedition led by paleontologist Barnum Brown discovered the type specimen of Ankylosaurus magniventris (AMNH 5895) in the Hell Creek Formation, near Gilbert Creek, Montana. The specimen (found by collector Peter Kaisen) consisted of the upper part of a skull, two teeth, part of the shoulder girdle, cervical, dorsal, and caudal vertebrae, ribs, and more than thirty osteoderms.[12] Brown scientifically described the animal in 1908; the genus name is derived from the Greek words ['αγκυλος] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/ankulos ('bent' or 'crooked'), referring to the medical term ankylosis, the stiffness produced by the fusion of bones in the skull and body, and [σαυρος] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/sauros ('lizard'). The name can be translated as "fused lizard", "stiff lizard", or "curved lizard". The type species name magniventris is derived from the Template:Lang-la ('great') and Template:Lang-la ('belly'), referring to the great width of the animal's body.[13][14]

The skeletal reconstruction accompanying the 1908 description restored the missing parts in a fashion similar to Stegosaurus, and Brown likened the result to the extinct armored mammal Glyptodon.[12] Contrary to modern depictions, Brown's reconstruction showed a strongly arched back, while the tail club was missing as it was unknown at the time.[15] Brown also reconstructed the armor plates in parallel rows running down the back; this arrangement, however, was purely hypothetical.[16] In a 1908 review of Brown's Ankylosaurus description, American palaeontologist Samuel Wendell Williston criticised the skeletal reconstruction as being based on too scanty remains, and claimed that Ankylosaurus was merely a synonym of the genus Stegopelta, which Williston had named in 1905. Williston also stated that a skeletal reconstruction of the related Polacanthus by Hungarian palaeontologist Franz Nopcsa was a better example of how ankylosaurs would have appeared in life.[17] The claim of synonymy was not accepted by other researchers, and the two genera are now considered distinct.[18]

Brown had collected seventy-seven osteoderms while excavating a Tyrannosaurus specimen in the Lance Formation of Wyoming in 1900. He mentioned these osteoderms (specimen AMNH 5866) in his description of Ankylosaurus, but thought they belonged to the Tyrannosaurus instead. Palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn also expressed this view when he described the Tyrannosaurus specimen as the now invalid genus Dynamosaurus in 1905. Later examination has shown them to be similar to those of Ankylosaurus, and that Brown had compared them with some Euoplocephalus osteoderms, which had been erroneously catalogued as belonging to Ankylosaurus at the AMNH.[2][19]

In 1910, another AMNH expedition led by Brown discovered an Ankylosaurus specimen (AMNH 5214) in the Scollard Formation by the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. This specimen included a complete skull, mandibles, the first and only tail club known of this genus, as well as ribs, vertebrae, limb bones, and armor. In 1947, fossil collectors Charles M. Sternberg and T.P. Channey collected a skull and mandible (specimen NMC 8880), a kilometre (0.6 miles) north of where the 1910 specimen was found. This is the largest known Ankylosaurus skull, but is badly preserved. A section of caudal vertebrae (specimen CCM V03) was discovered in the 1960s, in the Powder River drainage, Montana, also part of the Hell Creek Formation. In addition to these five incomplete specimens, many other isolated osteoderms and teeth have been found.[2]

In 1990, American palaeontologist Walter P. Coombs pointed out that the teeth of two skulls referred to A. magniventris differed from those of the holotype specimen in some details, and though he expressed a "considerate temptation" to name a new species of Ankylosaurus for these, he refrained from doing so, as the range of variation in the species was not completely documented. He also raised the possibility that the two teeth associated with the holotype specimen perhaps did not belong to it, as they were found in matrix within the nasal chambers.[9] Kenneth Carpenter accepted the teeth as belonging to A. magniventris and that all specimens belonged to the same species, noting that the teeth of other ankylosaurs are highly variable.[2]

Most of the known Ankylosaurus specimens were not scientifically described at length, though several palaeontologists planned to do so, until Carpenter redescribed the genus in 2004. Carpenter noted that Ankylosaurus has become the archetypal member of its group, and the best known ankylosaur in popular culture, perhaps due to a life-sized reconstruction of the animal being featured at the 1964 World's Fair in New York City.[2] Many traditional popular depictions show Ankylosaurus in a squatting posture and with a huge tail club being dragged over the ground. Modern reconstructions, however, show the animal with a more upright limb posture and with the tail being held clear off the ground. Likewise, large spines projecting sidewards from the body (similar to those of nodosaurs) are present in many traditional depictions, but such are not known from Ankylosaurus itself.[15]

Classification

Brown considered Ankylosaurus so distinct that he made it the type genus of a new family, Ankylosauridae (members of which are called ankylosaurids), typified by massive, triangular skulls, short necks, stiff backs, broad bodies, and osteoderms. He also classified Palaeoscincus (only known from teeth), and Euoplocephalus (then only known from a partial skull and osteoderms) as part of the family. Due to the fragmentary remains, Brown was unable to fully distinguish between Euoplocephalus and Ankylosaurus. Only having few, incomplete members of the family to compare with, he believed the group was part of the suborder Stegosauria.[12] In 1923, Osborn coined the name Ankylosauria (members of which are called ankylosaurs or ankylosaurians), thereby placing the ankylosaurids in their own suborder.[20]

Ankylosauria and Stegosauria are now grouped together within the clade Thyreophora. This group first appeared in the Sinemurian age, and survived for 135 million years, until disappearing in the Maastrichtian. They were widespread and inhabited a broad range of environments.[2][16] As more complete specimens and new genera have been discovered, theories about ankylosaurian interrelatedness have become more complex, and hypotheses have often changed between studies. In addition to Ankylosauridae, Ankylosauria has been divided into the families Nodosauridae, and sometimes Polacanthidae (these families lacked tail clubs).[21] Ankylosaurus is considered part of the subfamily Ankylosaurinae (members of which are called ankylosaurines) within Ankylosauridae.[21] Ankylosaurus appears to be most closely related to Anodontosaurus and Euoplocephalus.[22] The following cladogram is based on a 2015 phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosaurinae conducted by Arbour and Currie:[8]

Since Ankylosaurus and other Late Cretaceous North American ankylosaurids grouped with Asian genera (in a tribe the authors named Ankylosaurini), Arbour and Currie suggested that earlier North American ankylosaurids had gone extinct by the late Albian or Cenomanian ages of the Middle Cretaceous. Ankylosaurids thereafter recolonised North America from Asia during the Campanian or Turonian ages of the Late Cretaceous, and diversified there again, leading to genera such as Ankylosaurus, Anodontosaurus, and Euoplocephalus. This explains a 30 million year gap in the fossil record of North American ankylosaurids between these ages.[8]

Palaeobiology

Feeding

Like other ornithischians, Ankylosaurus was herbivorous. Its wide muzzle was adapted for non-selective low-browse cropping. The teeth of Ankylosaurus were worn on the face of the crowns, rather than on the tip of the crowns, as in nodosaurid ankylosaurs.[2] In 1982, Carpenter ascribed two very small teeth to baby Ankylosaurus, which originate from the Lance and Hell Creek Formations and measure 3.2 to 3.3 mm in length, respectively. The smaller tooth is heavily worn, leading Carpenter to suggest that ankylosaurids in general or at least the babies did not swallow their food whole but employed some sort of chewing.[10] Though ankylosaurs may not have fed on fibrous and woody plants, they may have had a more varied diet, including tough leaves and pulpy fruits.[23] Based on the broadness of the ribcage, Ankylosaurus may have digested through a hindgut fermentation system like modern herbivorous lizards, which have several chambers in their enlarged colon.[2]

In 1969, Austrian paleontologist Georg Haas concluded that despite the large size of ankylosaur skulls, the associated musculature was relatively weak. He also thought jaw movement was limited to up and down movements. Extrapolating from this, Haas suggested that ankylosaurs ate relatively soft non-abrasive vegetation.[24] However, later research on Euoplocephalus indicates that forward and sideways jaw movement was possible in these animals, the skull being able to withstand considerable forces.[25] A 2016 study of the dental occlusion (contact between the teeth) of ankylosaur specimens found that the ability for backwards (palinal) jaw movement evolved independently in different ankylosaur linages, including Late Cretaceous North American ankylosaurids like Ankylosaurus and Euoplocephalus.[26]

A specimen of Pinacosaurus preserves large paraglossalia (triangular bones or cartilages located in the tongue) which show signs of muscular stress, and it is thought this was a common feature of ankylosaurs. The researchers who examined the specimen suggested that ankylosaurs relied heavily on muscular tongues and hyobranchia (tongue bones) when feeding, since their teeth were fairly small and were replaced at a relatively slow rate. Some modern salamanders have similar tongue bones, and use prehensile tongues to pick up food.[23]

Airspaces and senses

In 1977, Polish paleontologist Teresa Maryańska proposed that the complex sinuses and nasal cavities of ankylosaurs may have lightened the weight of the skull, housed a nasal gland, or acted as a chamber for vocal resonance.[2][27] Carpenter rejected these hypotheses, arguing that tetrapod animals make sounds through the larynx, not the nostrils, and that reduction in weight was minimal, as the spaces only accounted for a small percent of the skull volume. He also considered a gland unlikely, and noted that the sinuses may not have had any specific function.[2] It is also been suggested that the respiratory passages were used to perform a mammal-like treatment of inhaled air, based on the presence and arrangement of specialized bones.[27]

A 2011 study of the nasal passages of Euoplocephalus supported their function as a heat and water balancing system, noting the extensive blood vessel system and an increased surface area for the mucosa membrane (used for heat and water exchange in modern animals). The researchers also supported the loops acting as a resonance chamber, comparable to the enlongated nasal passages of saiga antelope and looping trachea of cranes and swans. Reconstructions of the inner ear suggest adaptation to hearing at low frequencies, such as the low-toned resonant sounds possibly produced by the nasal passages. They disputed the possibility that the looping is related to olfaction (sense of smell) as the olfactionary region is pushed to the sides of the main airway.[28]

The shape of the nasal chambers of Ankylosaurus indicate that airflow was unidirectional, (looping through the lungs during inhalation and exhalation), although it may also have been bidirectional in the posterior nasal chamber, which directed air past the olfactory lobes.[2] The enlarged olfactory region of ankylosaurids indicates a well-developed sense of smell,[28] and the position of the orbits of Ankylosaurus suggest some stereoscopic vision.[2]

Limb movements

Reconstructions of ankylosaur forelimb musculature made by Coombs in 1978 suggest that the forelimbs bore the majority of the animal's weight, and were adapted for high force delivery on the front feet, possibly for food gathering. In addition, Coombs suggested that ankylosaurs may have been capable diggers, though the hoof-like structure of the manus would have limited fossorial activity. Ankylosaurs were likely to have been slow-moving and sluggish animals,[29][30] though they may have been capable of quick movements when necessary.[7]

Ontogeny

Studies of specimens of Pinacosaurus of different ages found that during ontogenetic development, the ribs of juvenile ankylosaurs fused with their vertebrae. The forelimbs strongly increased in robustness, while the hindlimbs did not become larger relative to the rest of the skeleton, further evidence that the arms bore most of the weight. In the cervical halfrings, the underlying bone band developed outgrowths connecting it with the underlying osteoderms, which simultaneously fused to each other.[31] On the skull, the middle bone plates first ossified at the snout and the rear rim; gradually the ossification extended towards the middle regions. On the rest of the body, the ossification process progressed from the neck onwards in the direction of the tail.[32]

Defense

The osteoderms of ankylosaurids were thin in comparison to those of other ankylosaurs, and appear to have been strengthened by randomly distributed cushions of collagen fibers. These were structurally similar to Sharpey's fibers, and were embedded directly into the bone tissue, a feature unique to ankylosaurids. This would have provided the ankylosaurids with an armor covering which was both lightweight and highly durable, being resistant to breakage and penetration by the teeth of predators.[33] The palpebral bones over the eyes may have provided additional protection for them.[34] Carpenter suggested in 1982 that the heavily vascularized armor may also have had a role in thermoregulation as in modern crocodilians.[35]

The tail club of Ankylosaurus seems to have been an active defensive weapon, capable of producing enough of an impact to break the bones of an assailant. The tendons of the tail were partially ossified and were not very elastic, allowing great force to be transmitted to the club when it was used as a weapon.[2] Coombs suggested in 1979 that several hindlimb muscles would have controlled the swinging of the tail, and that violent thrusts of the club would have been able to break the metatarsal bones of large theropods.[30]

A 2009 study estimated that ankylosaurids could swing their tails at 100 degrees laterally and the mainly cancellous clubs would have a lowered moment of inertia and been effective weapons. However, the study also found that while large ankylosaurid tail clubs were capable of breaking bones, medium and small clubs were not. Despite the feasibility of tail swinging, the researchers could not determine whether ankylosaurids used their clubs for defense against potential predators, in intraspecific combat or both.[36] In 1993, Tony Thulborn proposed that the tail club of ankylosaurids primarily acted as a decoy for the head, as he thought the tail too short and inflexible to have an effective reach; the "dummy head" would lure a predator close to the tail, where it could be stricken.[37] Carpenter has rejected this idea, as tail club shape is highly variable among ankylosaurids, even in the same genus.[2]

Palaeoecology

Ankylosaurus existed between 68 and 66 million years ago, in the final, or Maastrichtian, stage of the Late Cretaceous Period. It was among the last dinosaur genera that appeared before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The type specimen is from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, while other specimens have been found in the Lance Formation of Wyoming and the Scollard Formation in Alberta, Canada, all of which date to the end of the Cretaceous.[4][38] Fossils of Ankylosaurus are rare in these sediments, and the distribution of its remains suggest that it was restricted to the uplands of the formations, rather than the coastal lowlands. Another ankylosaur, an indeterminate nodosaur (formerly referred to as Edmontonia sp.), is also found in the same formations, but the range of the two genera does not seem to have overlapped. Their remains have so far not been found in the same localities, and the nodosaur appears to have inhabited the lowlands. The narrow muzzle of the nodosaur suggests it had a more selective diet than Ankylosaurus, further indicating ecological separation.[2]

The Hell Creek, Lance and Scollard Formations represent different sections of the western shore of the Western Interior Seaway that divided western and eastern North America during the Cretaceous. They represent a broad coastal plain, extending westward from the seaway to the newly formed Rocky Mountains. These formations are composed largely of sandstone and mudstone, which have been attributed to floodplain environments.[39][40][41] The regions where Ankylosaurus and other Late Cretaceous ankylosaurs have been found had a warm subtropical/temperate climate, which was monsoonal, had occasional rainfall, tropical storms, and forest fires.[26] In the Hell Creek Formation, many types of plants were supported, primarily angiosperms, with less common conifers, ferns and cycads. An abundance of fossil leaves found at dozens of different sites indicates that the area was largely forested by small trees.[42] Ankylosaurus shared its environment with dinosaurs including the ceratopsids Triceratops and Torosaurus, the hypsilophodont Thescelosaurus, the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus, an indeterminate nodosaur, the pachycephalosaurian Pachycephalosaurus, and the theropods Struthiomimus, Ornithomimus, Troodon, and Tyrannosaurus.[38][43]

See also

References

- ^ "Ankylosaurus". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Carpenter, K. (2004). "Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 41 (8): 961–86. Bibcode:2004CaJES..41..961C. doi:10.1139/e04-043.

- ^ a b Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ a b Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H., eds. (2004). "Ankylosauria". The Dinosauria. University of California Press. pp. 363–92. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Fastovsky, D. E.; Weishampel, D. B. (2005). "Ankylosauria: mass and gas". The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-521-81172-9.

- ^ Benson, RBJ; Campione, NE; Carrano, MT; Mannion, PD; Sullivan, C; Evans, David C.; et al. (2014). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLoS Biol. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author6=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first5=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Coombs, W. P. (1978). "Theoretical aspects of cursorial adaptations in dinosaurs". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 53 (4): 393–418. doi:10.1086/410790.

- ^ a b c d Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J. (2015). "Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (5): 1–60. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1990). "Teeth and taxonomy in ankylosaurs". Dinosaur systematics: Approaches and perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–79. ISBN 978-0-521-43810-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Carpenter, K. (1982). "Baby dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Lance and Hell Creek formations and a description of a new species of theropod". Rocky Mountain Geology. 20 (2): 123–134.

- ^ Arbour, Victoria M.; Currie, Philip J. (2015). "Ankylosaurid dinosaur tail clubs evolved through stepwise acquisition of key features". Journal of Anatomy. 227 (4): 514–23. doi:10.1111/joa.12363. PMID 26332595.

- ^ a b c Brown, B. (1908). "The Ankylosauridae, a new family of armored dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 24: 187–201. hdl:2246/1435.

- ^ Creisler, B. (July 7, 2003). "Dinosauria Translation and Pronunciation Guide A". Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R. (1980) [1871]. A Greek-English Lexicon (abridged ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ a b Glut, D. F. (1997). "Ankylosaurus". Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers. pp. 141–143. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1978). "The families of the ornithischian dinosaur order Ankylosauria" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 21 (1): 143–170.

- ^ Williston, S. W. (1908). "Review: The Ankylosauridae". The American Naturalist. 42 (501): 629–30. doi:10.1086/278987. JSTOR 2455817.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (2001). "Chapter 21: Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, K. (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. pp. 454–83. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1905). "Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs". Bulletin of the AMNH. 21 (14). American Museum of Natural History: 259–265. hdl:2246/1464.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1923). "Two Lower Cretaceous dinosaurs of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates. 95: 1–10. hdl:2246/3267.

- ^ a b Thompson, R. S.; Parish, J. C.; Maidment, S. C. R.; Barrett, P. M. (2012). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091.

- ^ Arbour, V.M.; Currie, P.J.; Badamgarav, D. (2014). "The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 172 (3): 631–652. doi:10.1111/zoj.12185.

- ^ a b Hill, R. V.; D'Emic, M. D.; Bever, G. S.; Norell, M. A. (2015). "A complex hyobranchial apparatus in a Cretaceous dinosaur and the antiquity of avian paraglossalia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 175 (4): 892–909. doi:10.1111/zoj.12293.

- ^ Haas, G. (1969). "On the jaw musculature of ankylosaurs". American Museum Novitates. 2399: 1–11. hdl:2246/2609.

- ^ Rybczynski, N.; Vickaryous, M. K. (2001). "Chapter 14: Evidence of Complex Jaw Movement in the Late Cretaceous Ankylosaurid, Euoplocephalus tutus (Dinosauria: Thyreophora)". In K. Carpenter (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 299–317. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- ^ a b Ősi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Mallon, J.; Bodor, E. R. (2016). "Diversity and convergences in the evolution of feeding adaptations in ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Historical Biology. 29 (4): 1–32. doi:10.1080/08912963.2016.1208194.

- ^ a b Maryanska, T. (1977). "Ankylosauridae (Dinosauria) from Mongolia" (PDF). Palaeontologia polonica. 37: 85–151.

- ^ a b "The internal cranial morphology of an armoured dinosaur Euoplocephalus corroborated by X-ray computed tomographic reconstruction" (PDF). Journal of Anatomy. 219 (6): 661–75. 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01427.x. PMC 3237876. PMID 21954840.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Coombs, W. (1978). "Forelimb muscles of the Ankylosauria (Reptilia, Ornithischia)". Journal of Paleontology. 52 (3): 642–57. JSTOR 1303969.

- ^ a b Coombs, W. (1979). "Osteology and myology of the hindlimb in the Ankylosauria (Reptillia, Ornithischia)". Journal of Paleontology. 53 (3): 666–84. JSTOR 1304004.

- ^ Burns, M; Tumanova, T; Currie, P (Jan 2015). "Postcrania of juvenile Pinacosaurus grangeri (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Alagteeg Formation, Alag Teeg, Mongolia: implications for ontogenetic allometry in ankylosaurs". Journal of Paleontology. 89 (1): 168–182. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.14.

- ^ Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Sissons, R.; Vickaryous, M. K. (2011). "Hands, feet, and behaviour in Pinacosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae)". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (3): 489–504. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0055.

- ^ Scheyer, T. M.; Sander, P. M. (2004). "Histology of ankylosaur osteoderms: implications for systematics and function". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 874–93. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0874:hoaoif]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524782.

- ^ Coombs W. (1972). "The Bony Eyelid of Euoplocephalus (Reptilia, Ornithischia)". Journal of Paleontology. 46 (5): 637–50. JSTOR 1303019..

- ^ Carpenter, K. (1982). "Skeletal and dermal armor reconstruction of Euoplocephalus tutus (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 19 (4): 689–97. Bibcode:1982CaJES..19..689C. doi:10.1139/e82-058.

- ^ Arbour, V. M. (2009). "Estimating impact forces of tail club strikes by ankylosaurid dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 4 (8): e6738. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6738A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006738. PMC 2726940. PMID 19707581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Thulborn, T. (1993). "Mimicry in ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Record of the South Australian Museum. 27: 151–58.

- ^ a b Weishampel, D. B.; Barrett, P. M.; Coria, R. A.; Le Loeuff, J.; Xu X.; Zhao X.; Sahni, A.; Gomani, E. M. P.; Noto, C. R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H.. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd). University of California Press. pp. 517–606. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ Lofgren, D. F. (1997). "Hell Creek Formation". In Currie, P.J.; Padian, K. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 302–03. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- ^ Breithaupt, B. H. (1997). "Lance Formation"". The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 394–95. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Eberth, D. A. (1997). "Edmonton Group". In Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 199–204. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- ^ Johnson, K. R. (1997). "Hell Creek Flora". In Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 300–02. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- ^ Bigelow, P. "Cretaceous 'Hell Creek Faunal Facies'; Late Maastrichtian". Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)