Jinn

Gen(Template:Lang-ar, al-jinn), also romanized as djinn or anglicized as genies (with the more broad meaning of spirits),[1] are supernatural creatures in early Arabian and later Islamic mythology and theology. An individual member of the jinn is known as a jinni, djinni, or genie (الجني, al-jinnī). They are mentioned frequently in the Quran (the 72nd sura is titled Sūrat al-Jinn) and other Islamic texts. The Quran says that the jinn were created from "mārijin min nar" (smokeless fire or a mixture of fire; scholars explained, this is the part of the flame, which mixed with the blackness of fire).[2][3] They are not purely spiritual, but are also physical in nature, being able to interact in a tactile manner with people and objects and likewise be acted upon. The jinn, humans, and angels make up the known sapient creations of God.[4] Like human beings, the jinn can be good, evil, or neutrally benevolent and hence have free will like humans.[5] The shaytan-jinn are called "devils" or "demons" and akin to demons in Christian tradition, including different types of evil invisible creatures, who are classified into the following three groups:[6]

- Satans/Devils/Demons (Iblis and his descendants)

- unbelievers among the ordinary jinn

- pagan deities (such as the deity Pazuzu)

Etymology

Jinn is an Arabic collective noun deriving from the Semitic root JNN (Template:Lang-ar, jann), whose primary meaning is "to hide". Some authors interpret the word to mean, literally, "beings that are concealed from the senses".[7] Cognates include the Arabic majnūn ("possessed", or generally "insane"), jannah ("garden"), and janīn ("embryo").[8] Jinn is properly treated as a plural, with the singular being jinni.

The earliest evidence of the word can be found in Persian, for the singular Jinni is the Avestic "Jaini", a wicked (female) spirit. Jaini were among various creatures in the possibly even pre-Zoroastrian mythology of peoples of Iran.[9][10]

The anglicized form genie is a borrowing of the French génie, from the Latin genius, a guardian spirit of people and places in Roman religion. It first appeared[11] in 18th-century translations of the Thousand and One Nights from the French,[12] where it had been used owing to its rough similarity in sound and sense.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Archeological evidence found in Northwestern Arabia seems to indicate the worship of jinn, or at least their tributary status, hundreds of years before Islam: an Aramaic inscription from Beth Fasi'el near Palmyra pays tribute to the "ginnaye", the "good and rewarding gods",[13][14] and it has been argued that the term is related to the Arabic jinn.[15]

Numerous mentions of jinn in the Quran and testimony of both pre-Islamic and Islamic literature indicate that the belief in spirits was prominent in pre-Islamic Bedouin religion.[16] However, there is evidence that the word jinn is derived from Aramaic, where it was used by Christians to designate pagan gods reduced to the status of demons, and was introduced into Arabic folklore only late in the pre-Islamic era.[16] Julius Wellhausen has observed that such spirits were thought to inhabit desolate, dingy, and dark places and that they were feared.[16] One had to protect oneself from them, but they were not the objects of a true cult.[16]

Islamic theology

Islamic theology generally distinguishes between angels, demons and jinn among supernatural creatures.[17] Others assert, due to its primary meaning "to hide" or "to conceal", Jinn can refer to angels[18][19] and to demons depending on their behavior towards humans. But they are often depicted as a creature beside demons and angels and threaten as invisible sapient creatures among humans.[20] Modernist commentators, on the basis of the words meaning, refer the jinn to microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses[21] or undetectable uncivilized persons.[22] Other early Muslims like Al-Jahiz and Al-Masudi criticised the jinn-belief, and stated they rather have their origin in hallucinations and imaginings.[23] But this view was opposed by the most hanbali theologians like Ibn Taymiyyah.[24]

Jinn (and variaties of the word) are mentioned 29 times in the Quran: Surah 72 (named Sūrat al-Jinn) is named after the jinn, and has a passage about them. Surah 114 (Sūrat al-Nās) mentions jinn in the last verse.[25] The Quran also mentions that Muhammad was sent as a prophet to both "humanity and the jinn", and that prophets and messengers were sent to both communities.[26][27] Traditionally Surah 72 is held to tell about the revelation to jinn community.

Jinn as Pre-Adamites

According to early Sunni tafsir[28] from Tabari, the humans are successors (Arab: Khalifa ) to the Jinn, who are said to have inhabited and ruled the earth before. According to this tradition, the Jinn were similar to human society and governed by 72 kings.[29][30] Eventually they became infidels and started corruption, fought each other and shed blood. God sent admonishers to them, but the Jinn continued doing evil. They then became more impious, God sent angels who drove away the Jinn and killed the most of them, thus humans could replace them. These fighting angels, were called jinn as well, due to their origin in Jannah,[31] and also created from fire, but do not belong to the same species as the terrestrial creature called Jinn, the latter created from a mixture of fire and the angels here, from the fires of samum.[32] Since angels are generally created from light, this tribe was special in its creation.

Jinn and Devils

While generally islamic theology distinguishes between Jinn and demons, some early traditions from Hasan of Basra merged demons, jinn and Iblis to one category of malevolent invisible creatures, created from fire in general, contrasting the angels created from light.[33] Accordingly, no distinction is made between the meaning fire of samum and smokeless fire. Yet, the jinn can become believers, but are still capable to become infidels by their own decision and are then called demons. Ibn Taymiyyah, an influential late medieval theologian whose writings would later become the source of Wahhabism,[34] believed the jinn to be generally "ignorant, untruthful, oppressive and treacherous."[35] He held that the jinn account for much of the "magic" perceived by humans, cooperating with magicians to lift items in the air unseen, delivering hidden truths to fortune tellers, and mimicking the voices of deceased humans during seances.[35]

Those who distinguish Shayateen-Jinn as a separate class of supernatural creatures, assert Shayateen (demons/devils) are descendants or helpers of Iblis. While Islam apply Jinn to spirits and deities of other cultures, but without demonizing them,[36] however reduced their status to lower creatures subjected to judgement on the "Last Day"; the Shayateen perform the role of devils, tempting human to sin and cause despair and doubt. Among the Shayateen — the Marid and the Afarit are the strongest types.[37]

Jinn as imaginal beings

Some scholars like Ibn Arabi, suggested Jinn are indeed imaginal but not unreal, therefore regarded to be spiritual in essence. They truly exist but react to feelings and thoughts of humans. They came from the imaginal realm, the place where the unseen takes on visible forms. As a world where emotions become predominant, it affects our world through dreams and psychological functions. Therefore, jinn are not monsters or beasts, but thoughts, that were in the world before the existence of the men, taking on physical shapes in certain conditions.[38]

Solomon and the Jinn

According to Islam, Solomon was endowed with the ability to talk to animals and jinn and was therefore king over humans and jinn.

And before Solomon were marshalled his hosts, of jinn and men and birds, and they were all kept in order and ranks. (Quran 27:17)

With a ring, given by an angel, he enslaved demons and ordered them to perform a number of tasks, like building the first temple.[39] According to Islamic belief, Solomon was accused of sorcery, but the Quran refuses this accusation. The Quran relates that Solomon died while he was leaning on his staff. As he remained upright, propped on his staff, the jinn thought he was still alive and supervising them, so they continued to work. They realized the truth only when Allah sent a creature to crawl out of the ground and gnaw at Solomon's staff until his body collapsed. The Quran then comments that if they had known the unseen, they would not have stayed in the humiliating torment of being enslaved.

Then, when We decreed (Solomon's) death, nothing showed them his death except a little worm of the earth, which kept (slowly) gnawing away at his staff: so when he fell down, the jinn saw plainly that if they had known the unseen, they would not have tarried in the humiliating penalty (of their task). (Qurʾan 34:14)

Ibn al-Nadim, in his Kitāb al-Fihrist, describes a book that lists 70 Jinn led by Fuqtus, including several Jinn appointed over each day of the week[40][41] Bayard Dodge, who translated al-Fihrist into English, notes that most of these names appear in the Testament of Solomon.[40] A collection of late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century magico-medical manuscripts from Ocaña, Spain describes a different set of 72 Jinn (termed "Tayaliq") again under Fuqtus (here named "Fayqayțūš" or Fiqitush), blaming them for various ailments.[42][43] According to these manuscripts each Jinn was brought before King Solomon and ordered to divulge their "corruption" and "residence" while the Jinn King Fiqitush gave Solomon a recipe for curing the ailments associated with each Jinn as they confessed their transgressions.[44]

Qarīn

A related belief is that every person is assigned one's own special jinni, as a counterpart in the spiritual realm to the person in the human realm,[38] also called a qarīn, and if the qarin is evil it could whisper to people's souls and tell them to submit to evil desires.[45][46][47] The notion of a qarin is not universally accepted among all Muslims, but it is generally accepted that Shayṭān whispers in human minds, and he is assigned to each human being.[clarification needed]

In a hadith recorded by Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, the companion Abdullah, son of Masud reported: 'The Prophet Muhammad said: 'There is not one of you who does not have a jinnī appointed to be his constant companion (qarīn).' They said, 'And you too, O Messenger of Allah?' He said, 'Me too, but Allah has helped me and he has submitted, so that he only helps me to do good.' [48]

In Islamic folklore

With the spread of Islam, spirits, fairies and deities of other cultures become Jinn, thus the term Jinn was extended to other beings, like in Persia, to Diw and Peris, while some scholars still made a distinction between the Jinn mentioned in the Quran and supernatural beings from Persia.[49] When jinns are called "fire spirits" it does not refer to their current nature, rather to their origin.[50] Developed from various traditions and local folklore, Jinn are said to be able to possess humans, especially Morocco has a lot of possession traditions, including exorcism rituals.[51] Jinn are often depicted as monstrous and anthropomorphized creatures with body parts from different animals.[52] However according to Zubayr ibn al-Awam, who is held to accompanied Muhammad during his lecture to the Jinn, described them as shadowy ghosts.[53] Originated from a few traditions (hadith), jinn can be divided into three classes: those who have wings and fly in the air, those who resemble snakes and dogs, and those who travel about ceaselessly.[54] Described them as creatures of different forms; some resembling vultures and snakes, others tall men in white garb.[55] They may even appear as dragons, onagers, or any number of other animals, but with an exception of 'udhrut from Yemeni folklore, not in wolves, since wolves are hold to be foes to the Jinn,[56] disable them to vanish.[57] In addition to their animal forms, the jinn occasionally assume human form to mislead and destroy their human victims.[58] Therefore, Jinn are not considered to be purely spiritual, but resembling sapient beast, which may be empowered to shapeshift for a while or be able to myteriously disappear.[59] Certain hadiths have also claimed that the jinn may subsist on bones, which will grow flesh again as soon as they touch them, and that their animals may live on dung, which will revert to grain or grass for the use of the jinn flocks.[60] Jinn are also quite willing to have amorous affairs with humans.[61] The social organization of the jinn community resembles that of humans; e.g., they have kings, courts of law, weddings, mourning rituals and practise religion (in addition to Islam, it can also be Christianity or Judaism).[62]

Seven kings of the Jinn are traditionally associated with days of the week.[63]

- Sunday: Al-Mudhib (Abu 'Abdallah Sa'id)

- Monday: Murrah al-Abyad Abu al-Harith (Abu al-Nur)

- Tuesday: Abu Mihriz (or Abu Ya'qub) Al-Ahmar

- Wednesday: Barqan Abu al-'Adja'yb

- Thursday: Shamhurish (al-Tayyar)

- Friday: Abu Hasan Zoba'ah (al-Abyad)

- Saturday: Abu Nuh Maimun

In Muslim cultures

The stories of the jinn can be found in various Muslim cultures around the world. In Sindh the concept of the Jinni was introduced during the Abbasid Era and has become a common part of the local folklore which also includes stories of both male jinn called "jinn" and female jinn called "jiniri". Folk stories of female jinn include stories such as the Jejhal Jiniri.

Other acclaimed stories of the jinn can be found in the One Thousand and One Nights story of "The Fisherman and the Jinni";[64] more than three different types of jinn are described in the story of Ma‘ruf the Cobbler;[65][66] two jinn help young Aladdin in the story of Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp;[67] as Ḥasan Badr al-Dīn weeps over the grave of his father until sleep overcomes him, and he is awoken by a large group of sympathetic jinn in the Tale of ‘Alī Nūr al-Dīn and his son Badr ad-Dīn Ḥasan.[68] In some stories, jinn are credited with the ability of instantaneous travel (from China to Morocco in a single instant); in others, they need to fly from one place to another, though quite fast (from Baghdad to Cairo in a few hours). Nevertheless, jinn figments from such stories are generally considered to be fictional, while jinn are considered to be part of the concrete world.[50]

During the Rwandan genocide, both Hutus and Tutsis avoided searching local Rwandan Muslim neighborhoods because they widely believed the myth that local Muslims and mosques were protected by the power of Islamic magic and the efficacious jinn.[citation needed] In Cyangugu, arsonists ran away instead of destroying the mosque because they believed that jinn were guarding the mosque and they feared their wrath.[69]

In science

Sleep paralysis is conceptualized as a "Jinn attack" by many sleep paralysis sufferers in Egypt as discovered by Cambridge neuroscientist Baland Jalal.[70] A scientific study found that as many as 48 percent of those who experience sleep paralysis in Egypt believe it to be an assault by the Jinn.[70] Almost all of these sleep paralysis sufferers (95%) would recite verses from the Quran during sleep paralysis to prevent future "Jinn attacks". In addition, some (9%) would increase their daily Islamic prayer (salah) to get rid of these attacks by Jinn.[70] Sleep paralysis is generally associated with great fear in Egypt, especially if believed to be supernatural in origin.[71]

Other cultures

Similarities to Judaism

Besides angels, Jewish lore notices other types of supernatural creatures including Shedim, which are akin to the Islamic concept of Jinn. They are said to eat, drink, procreate, and die, are also mostly invisible and in some accounts, they inhabited the earth before mankind until human beings replaced them, similar to the Jinn in Islam.[72][73] In addition the Shedim are also mentioned helping Solomon building the first temple. Their king Asmodeus appears both in Islamic lore and in the Talmud as a rebel against Solomon.[39]

Buddhism

Similar to the islamic idea of spiritual entities converting to One's religion can be found on Buddhism lore. Accordingly Bhudda preached among humans and Deva, spiritual entities who are like humans subject to the cycle of life.[74][75]

In the Guanche mythology

In Guanche mythology from Tenerife in the Canary Islands, there existed the belief in beings that were similar to genies,[76] such as the maxios or dioses paredros ("attendant gods", domestic and nature spirits) and tibicenas (evil genies), as well as the demon Guayota (aboriginal god of evil) that, like the Arabic Iblīs, is sometimes identified with a genie.[77] The Guanches were the Berber autochthones of the Canary Islands.

Christian sources

Van Dyck's Arabic translation of the Old Testament uses the alternative collective plural jann (الجان al-jānn) to render the Hebrew word usually translated into English as "familiar spirit" (אוב , Strong #0178) in several places (Leviticus 19:31, 20:6, 1 Samuel 28:3,7,9, 1 Chronicles 10:13).[78]

In popular culture

The jinn frequently occurs as a character or plot element in fiction. Two other classes of jinns, the ifrit and the marid, have also been represented in fiction as well.

Genies appear in film in various forms, such as the genie freed by Abu, the eponymous character in the 1940 film Thief of Bagdad.[79]

A Jinn makes a short appearance in the novel American Gods by Neil Gaiman, originally published in 2001. American Gods was also made into a TV series for the Starz television cable television network in 2017. The television adaptation also features a Jinn.

The protagonist of the Bartimaeus Sequence is a jinni, and the books have an established hierarchy that include other types of spirit; imps, foliots, djinn, afrits, and marids (to use the author's own spelling). In this interpretation, jinn and all other spirits are not physical beings, but are instead from another dimension of chaos called "The Other Place". To exist on Earth at all, magicians must summon sprits and force them to take some kind of form, something so alien that it causes all spirits pain. As a result magicians must put measures in place to force spirits to do what they want in a form of magical slavery.

Gallery

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

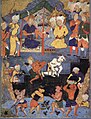

-

Zulqarnayn with the help of some jinn, building the Iron Wall to keep the barbarian Gog and Magog from civilized peoples (16th century Persian miniature)

-

Aladdin flying away with two people, from the Arabian Nights, c. 1900

-

The sleeping genie and the lady, from the Arabian Nights, illustrated by Sir John Tenniel, 1912

-

page from 14th/15th-century manuscript Kitab al-Bulhan or Book of Wonders

See also

- Daeva

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Demonology

- Devil (Islam)

- Djinn (comics)

- Fairy

- Genie in popular culture

- Genius loci

- Genius (mythology)

- Ghoul (Jinn who dwell within graveyards)

- Houri

- Marid

- Nasnas

- Peri

- Qareen

- Qutrub

- Rig-e Jenn

- Shayṭān (Troops of Demons headed by Iblis)

- Shedim

- Theriocephaly

- Will of the wisp

- Winged genie

- Yazata

- Exorcism in Islam

References

- ^ "jinn - Definition of jinn in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English.

- ^ Benjamin W. McCraw, Philosophical Approaches to Demonology Robert Arp Routledge 2017 ISBN 978-1-315-46675-0

- ^ Qur’ān 55:15

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 19

- ^ El-Zein, Amira. "Jinn", 420–421, in Meri, Joseph W., Medieval Islamic Civilization – An Encyclopedia.

- ^ name="Robert Lebling ">Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 page 141

- ^ Edward William Lane. "An Arabic-English Lexicon". Archived from the original on 8 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). p. 462. - ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (4 ed.). Urbana, Illinois: Spoken Language Services. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-87950-003-0.

- ^ Tisdall, W. St. Clair. The Original Sources of the Qur'an, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1905

- ^ The Religion of the Crescent or Islam: Its Strength, Its Weakness, Its Origin, Its Influence, William St. Clair Tisdall, 1895

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. "genie, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2014.

- ^ Arabian Nights' entertainments, vol. Vol. I, 1706, p. 14

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help). - ^ Hoyland, R. G., Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, p. 145.

- ^ Jonathan A.C. Brown. Muhammad: A Very Short Introduction Oxford, 2011.

- ^ Javier Teixidor. The Pantheon of Palmyra. Brill Archive, 1979. p. 6

- ^ a b c d Irving M. Zeitlin (19 March 2007). The Historical Muhammad. Polity. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-7456-3999-4.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 22

- ^ Scott B. Noegel, Brannon M. Wheeler The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism Scarecrow Press 2010 ISBN 978-1-461-71895-6 page 170

- ^ University of Michigan Muhammad Asad: Europe's Gift to Islam, Band 1 Truth Society 2006 ISBN 978-9-693-51852-8 page 387

- ^ Gerda Sengers Women and Demons: Cultic Healing in Islamic Egypt BRILL 2013 ISBN 978-9-004-12771-5 page 254

- ^ Simon Ross Valentine Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice Hurst Publishers 2008 ISBN 978-1-850-65916-7 page 143

- ^ U. A. B. Razia Akter Banu Islam in Bangladesh BRILL 1992 ISBN 978-9-004-09497-0 page 57

- ^ Hasan M. El-Shamy Religion Among the Folk in Egypt Praeger 2009 ISBN 978-0-275-97948-5 p. 28.

- ^ Tobias Nünlist Dämonenglaube im Islam Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015 ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4 p. 60. (German)

- ^ Quran 116:4–4

- ^ Quran 51:56–56

- ^ Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb al-Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, I, p. 68; Abū al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān, pp. 193, 341

- ^ Oxford University Press Tafsir: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide Oxford University Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-199-80430-6 page 8

- ^ Patrick Hughes, Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services 1995 page 134 ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2

- ^ Gabriel Said Reynolds The Qur'an and Its Biblical Subtext Routledge 2010 ISBN 978-1-135-15020-4 page 41

- ^ tafsir-al-tabari Sura 2 vers 34 - page 239

- ^ Brannon Wheeler Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis A&C Black 2002 ISBN 9780826449566 Page 16

- ^ ʻUmar Sulaymān Ashqar The World of the Jinn and Devils Islamic Books 1998 p. 56.

- ^ "Ibn Taymiyyah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ a b Ibn Taymiyyah, al-Furqān bayna awliyā’ al-Raḥmān wa-awliyā’ al-Shayṭān ("Essay on the Jinn"), translated by Abu Ameenah Bilal Phillips

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 52

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Patrick. Dictionary of Islam. 1885. "Genii" pp. 133-138.

- ^ a b Kelly Bulkeley, Kate Adams, Patricia M. Davis Dreaming in Christianity and Islam: Culture, Conflict, and Creativity Rutgers University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-813-54610-0 page 144

- ^ a b Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3

- ^ a b Bayard Dodge, ed. and trans. The Fihrist of al-Nadim: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. pp. 727-8.

- ^ Robert Lebling. Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B. Taurus, 2010. p.38

- ^ Celia del Moral. Magia y Superstitión en los Manuscritos de Ocaña (Toledo). Siglos XIV-XV. Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the Union Européenne des Arabisants et Islamisants, Part Two; A. Fodor, ed. Budapest, 10–17 September 2000. pp.109-121

- ^ Joaquina Albarracin Navarro & Juan Martinez Ruiz. Medicina, Farmacopea y Magia en el "Misceláneo de Salomón". Universidad de Granada, 1987. p.38 et passim

- ^ Shadrach, Nineveh (2007). The Book of Deadly Names. Ishtar Publishing. ISBN 978-0978388300.

- ^ Quran 72:1–2

- ^ Quran 15:18–18

- ^ Sahih Muslim, No. 2714

- ^ Sahih Muslim, Book 39, Hadith No. 6759.

- ^ Cosimo, Inc Arabian Nights, in 16 volumes: Volume XIII, Band 13 2008 ISBN 978-1-605-20603-5 page 256

- ^ a b Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3

- ^ Joseph P. Laycock Spirit Possession around the World: Possession, Communion, and Demon Expulsion across Cultures: Possession, Communion, and Demon Expulsion across Cultures ABC-CLIO 2015 ISBN 978-1-610-69590-9 page 243

- ^ name="Robert Lebling ">Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 page 120

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 64

- ^ Fozūnī, p. 526

- ^ Fozūnī, pp. 525–526

- ^ name="ReferenceA">Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 page 98

- ^ Kolaynī, I, p. 396; Solṭān-Moḥammad, p. 62

- ^ Mīhandūst, p. 44

- ^ Edward Scribner Ames The Psychology of Religious Experience Wipf and Stock Publishers 2010 ISBN 978-1-608-99377-2 page 105

- ^ Abu’l-Fotūḥ, XVII, pp. 280–281

- ^ Dan Burton, David Grandy Magic, Mystery, and Science: The Occult in Western Civilization Indiana University Press 2004 ISBN 978-0-253-21656-4 page 144

- ^ Ṭūsī, p. 484; Fozūnī, p. 527

- ^ Robert Lebling (30 July 2010). Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-85773-063-3.

- ^ The fisherman and the Jinni at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ Idries Shah - Tales of the Dervishes at ISF website

- ^ "MA'ARUF THE COBBLER AND HIS WIFE".

- ^ The Arabian Nights - ALADDIN; OR, THE WONDERFUL LAMP at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ The Arabian Nights - TALE OF NUR AL-DIN ALI AND HIS SON BADR AL-DIN HASAN at About.com Classic Literature

- ^ Kubai, Anne (April 2007). "Walking a Tightrope: Christians and Muslims in Post-Genocide Rwanda". Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. 18 (2). Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group: 219–235. doi:10.1080/09596410701214076.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Jalal, Baland; Simons-Rudolph, Joseph; Jalal, Bamo; Hinton, Devon E. (1 October 2013). "Explanations of sleep paralysis among Egyptian college students and the general population in Egypt and Denmark". Transcultural Psychiatry. 51 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1177/1363461513503378.

- ^ Jalal, Baland; Hinton, Devon E. (1 September 2013). "Rates and Characteristics of Sleep Paralysis in the General Population of Denmark and Egypt". Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 37 (3): 534–548. doi:10.1007/s11013-013-9327-x. ISSN 0165-005X.

- ^ Carol K. Mack, Dinah Mack Italic textA Field Guide to Demons, Vampires, Fallen Angels and Other Subversive Spirits Skyhorse Publishing 2013 ISBN 978-1-628-72150-8

- ^ "Shedim: Eldritch Beings from Jewish Folklore". 7 March 2014.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 165

- ^ Marie Musæus-Higgins Poya Days Asian Educational Services 1925 ISBN 978-8-120-61321-8 page 14

- ^ "Los guanches y los perros llegaron juntos a Tenerife". 7 July 2013.

- ^ Guanche Religion Archived 2 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Arabic Bible - Arabic Bible Outreach Ministry". www.arabicbible.com.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (6 December 1940). "'The Thief of Bagdad,' a Delightful Fairy Tale, at the Music Hall--'Lady With Red Hair,' at the Palace". New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Al-Ashqar, Dr. Umar Sulaiman (1998). The World of the Jinn and Devils. Boulder, CO: Al-Basheer Company for Publications and Translations.

- Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. 1995.

- "Genie". The Oxford English Dictionary. Second edition, 1989.

- Abu al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān IX-XVII (pub. so far), Tehran, 1988.

- Moḥammad Ayyūb Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, ed. J. Matīnī, Tehran, 1971.

- A. Aarne and S. Thompson, The Types of the Folktale, 2nd rev. ed., Folklore Fellows Communications 184, Helsinki, 1973.

- Abu’l-Moayyad Balkhī, Ajā’eb al-donyā, ed. L. P. Smynova, Moscow, 1993.

- A. Christensen, Essai sur la Demonologie iranienne, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser, 1941.

- R. Dozy, Supplément aux Dictionnaires arabes, 3rd ed., Leyden, 1967.

- H. El-Shamy, Folk Traditions of the Arab World: A Guide to Motif Classification, 2 vols., Bloomington, 1995.

- Abū Bakr Moṭahhar Jamālī Yazdī, Farrokh-nāma, ed. Ī. Afshār, Tehran, 1967.

- Abū Jaʿfar Moḥammad Kolaynī, Ketāb al-kāfī, ed. A. Ghaffārī, 8 vols., Tehran, 1988.

- Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, Beirut, 1968.

- L. Loeffler, Islam in Practice: Religious Beliefs in a Persian Village, New York, 1988.

- U. Marzolph, Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens, Beirut, 1984. Massé, Croyances.

- M. Mīhandūst, Padīdahā-ye wahmī-e dīrsāl dar janūb-e Khorāsān, Honar o mordom, 1976, pp. 44–51.

- T. Nöldeke "Arabs (Ancient)", in J. Hastings, ed., Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics I, Edinburgh, 1913, pp. 659–73.

- S. Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, rev. ed., 6 vols., Bloomington, 1955.

- S. Thompson and W. Roberts, Types of Indic Oral Tales, Folklore Fellows Communications 180, Helsinki, 1960.

- Solṭān-Moḥammad ibn Tāj al-Dīn Ḥasan Esterābādī, Toḥfat al-majāles, Tehran.

- Moḥammad b. Maḥmūd Ṭūsī, Ajāyeb al-makhlūqāt va gharā’eb al-mawjūdāt, ed. M. Sotūda, Tehran, 1966.

Further reading

- Crapanzano, V. (1973) The Hamadsha: a study in Moroccan ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1976) The Religion of Palmyra. Leiden, Brill.

- El-Zein, Amira (2009) Islam, Arabs, and the intelligent world of the Jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3200-9.

- El-Zein, Amira (2006) "Jinn". In: J. F. Meri ed. Medieval Islamic civilization – an encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon, Routledge, pp. 420–421.

- Goodman, L.E. (1978) The case of the animals versus man before the king of the Jinn: A tenth-century ecological fable of the pure brethren of Basra. Library of Classical Arabic Literature, vol. 3. Boston, Twayne.

- Maarouf, M. (2007) Jinn eviction as a discourse of power: a multidisciplinary approach to Moroccan magical beliefs and practices. Leiden, Brill.

- Zbinden, E. (1953) Die Djinn des Islam und der altorientalische Geisterglaube. Bern, Haupt.

External links

- Use dmy dates from September 2010

- Jinn

- Albanian mythology

- Arabian mythology

- Arabian legendary creatures

- Arabic words and phrases

- Deities, spirits, and mythic beings

- Egyptian folklore

- Iranian folklore

- Islamic legendary creatures

- Malaysian mythology

- Indian folklore

- Quranic figures

- Supernatural legends

- Turkish folklore

- Islamic terminology