G7

| Group of Seven and the European Union |

|---|

|

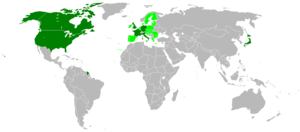

The Group of 7 (G7) is a group consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. These countries represent more than 64% of the net global wealth ($263 trillion)[1] and all have a very high Human Development Index. The G7 countries also represent 46% of the global GDP evaluated at market exchange rates and 32% of the global purchasing power parity GDP.[2] The European Union is also represented within the G7.

The 43rd G7 summit was held in Taormina (ME), Italy in May 2017.

History

The G7 originates with the Group of Six. It was founded ad hoc in 1975, consisting of finance ministers and central bank governors from France, West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, when Giscard d'Estaing invited them for an "informal gathering at the chateau of Rambouillet, near Paris [...] in a relaxed and private setting".[3] The intent was "to discuss current world issues (dominated at the time by the oil crisis) in a frank and informal manner".[3] The G6 followed an unofficial gathering starting in 1974 of senior financial officials from the United States, the United Kingdom, West Germany, Japan and France. They were called the "Library group" or the "Group of Five" because they met informally in the White House Library in Washington, DC.[4]: 34 (this is not to be confused with the current, but completely different "Group of Five", a group of the five top nations with emerging economies formed in 2005).

Canada became the seventh member to begin attending the summits in 1976, after which the name 'Group 7' or G7 Summit was used.[3]

Following 1994's G7 summit in Naples, Russian officials held separate meetings with leaders of the G7 after the group's summits. This informal arrangement was dubbed the Political 8 (P8) – or, colloquially, the G7+1. At the invitation of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair and President of the United States Bill Clinton,[5] Russian President Boris Yeltsin was invited first as a guest observer, later as a full participant. It was seen as a way to encourage Yeltsin's capitalist reforms.[citation needed] After the 1997 meeting Russia was formally invited to the next meeting and formally joined the group in 1998, resulting in a new governmental political forum, the Group of Eight, or G8.[3] However Russia was ejected from the G8 political forum in 2014 following the Russian annexation of Crimea.

Function

The organization was founded to facilitate shared macroeconomic initiatives by its members in response to the collapse of the exchange rate 1971, during the time of the Nixon Shock, the 1970s energy crisis and the ensuing recession.[6] Its goal was fine tuning of short term economic policies among participant countries to monitor developments in the world economy and assess economic policies.[citation needed]

Work

Since 1975, the group meets annually on summit site to discuss economic policies; since 1987, the G7 finance ministers have met at least semi-annually, up to 4 times a year at stand-alone meetings.[7]

In 1996, the G7 launched an initiative for the 42 heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC).[8]

In 1999, the G7 decided to get more directly involved in "managing the international monetary system" through the Financial Stability Forum, formed earlier in 1999 and the G-20, established following the summit, to "promote dialogue between major industrial and emerging market countries".[9] The G7 also announced their plan to cancel 90% of bilateral, and multilateral debt for the HIPC, totaling $100 billion.[citation needed]

In 2005 the G7 announced, debt reductions of "up to 100%" to be negotiated on a "case by case" basis.[citation needed]

In 2008 the G7 met twice in Washington, D.C. to discuss the global financial crisis of 2007-2010[10] and in February 2009 in Rome.[11][12] The group of finance ministers pledged to take "all necessary steps" to stem the crisis.[13]

On 2 March 2014, the G7 condemned the "Russian Federation's violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine."[14] The G7 stated "that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) remains the institution best prepared to help Ukraine address its immediate economic challenges through policy advice and financing, conditioned on needed reforms", and that the G7 was "committed to mobilize rapid technical assistance to support Ukraine in addressing its macroeconomic, regulatory and anti-corruption challenges."[14]

On 24 March 2014, the G7 convened an emergency meeting in response to the Russian Federation's annexation of Crimea at the Dutch Catshuis, located in The Hague because all G7 leaders were already present to attend the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit. This was the first G7 meeting neither taking place in a member nation nor having the host leader participating in the meeting.[15]

On 4 June 2014 leaders at the G7 summit in Brussels, condemned Moscow for its "continuing violation" of Ukraine's sovereignty, in their joint statement and stated they were prepared to impose further sanctions on Russia.[16] This meeting was the first since Russia was expelled from the group G8 following its annexation of Crimea in March.[16]

The annual G7 leaders summit is attended by the heads of government.[17] The member country holding the G7 presidency is responsible for organizing and hosting the year's summit.

The serial annual summits can be parsed chronologically in arguably distinct ways, including as the sequence of host countries for the summits has recurred over time, series, etc.[18]

List of summits

| Date | Host | Host leader | Location held | Website | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 15–17 November 1975 | France | Valéry Giscard d'Estaing | Rambouillet (Castle of Rambouillet) | G6 Summit | |

| 2nd | 27–28 June 1976 | United States | Gerald R. Ford | Dorado, Puerto Rico[19] | Also called "Rambouillet II". Canada joined the group, forming the G7[19] | |

| 3rd | 7–8 May 1977 | United Kingdom | James Callaghan | London | President of the European Commission was invited to join the annual G-7 summits | |

| 4th | 16–17 July 1978 | West Germany | Helmut Schmidt | Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| 5th | 28–29 June 1979 | Japan | Masayoshi Ōhira | Tokyo | ||

| 6th | 22–23 June 1980 | Italy | Francesco Cossiga | Venice | Prime Minister Ōhira died in office on 12 June; Foreign Minister Saburō Ōkita led the delegation which represented Japan in his place. | |

| 7th | 20–21 July 1981 | Canada | Pierre E. Trudeau | Montebello, Québec | ||

| 8th | 4–6 June 1982 | France | François Mitterrand | Versailles | ||

| 9th | 28–30 May 1983 | United States | Ronald Reagan | Williamsburg, Virginia | ||

| 10th | 7–9 June 1984 | United Kingdom | Margaret Thatcher | London | ||

| 11th | 2–4 May 1985 | West Germany | Helmut Kohl | Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| 12th | 4–6 May 1986 | Japan | Yasuhiro Nakasone | Tokyo | ||

| 13th | 8–10 June 1987 | Italy | Amintore Fanfani | Venice | ||

| 14th | 19–21 June 1988 | Canada | Brian Mulroney | Toronto, Ontario | ||

| 15th | 14–16 July 1989 | France | François Mitterrand | Paris | ||

| 16th | 9–11 July 1990 | United States | George H. W. Bush | Houston | ||

| 17th | 15–17 July 1991 | United Kingdom | John Major | London | ||

| 18th | 6–8 July 1992 | Germany | Helmut Kohl | Munich, Bavaria | ||

| 19th | 7–9 July 1993 | Japan | Kiichi Miyazawa | Tokyo | ||

| 20th | 8–10 July 1994 | Italy | Silvio Berlusconi | Naples | ||

| 21st | 15–17 June 1995 | Canada | Jean Chrétien | Halifax, Nova Scotia | [20] | |

| 22nd | 27–29 June 1996 | France | Jacques Chirac | Lyon | International organizations' debut to G7 Summits periodically. The invited ones here were: United Nations, World Bank, International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization.[21] | |

| 23rd | 20–22 June 1997 | United States | Bill Clinton | Denver | [22] | Russia joins the group, forming G8 |

| 24th | 15–17 May 1998 | United Kingdom | Tony Blair | Birmingham | [23] | |

| 25th | 18–20 June 1999 | Germany | Gerhard Schröder | Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia | [24] | First Summit of the G-20 major economies at Berlin |

| 26th | 21–23 July 2000 | Japan | Yoshiro Mori | Nago, Okinawa | [25] | Formation of the G8+5 starts, when South Africa was invited. Until the 38th G8 summit in 2012, it has been invited to the Summit annually without interruption. Also, with permission from a G8 leader, other nations were invited to the Summit on a periodical basis for the first time. Nigeria, Algeria and Senegal accepted their invitations here. The World Health Organization was also invited for the first time.[21] |

| 27th | 20–22 July 2001 | Italy | Silvio Berlusconi | Genoa | [26] | Leaders from Bangladesh, Mali and El Salvador accepted their invitations here.[21] Demonstrator Carlo Giuliani is shot and killed by police during a violent demonstration. One of the largest and most violent anti-globalization movement protests occurred for the 27th G8 summit.[27] Following those events and the September 11 attacks two months later in 2001, the G8 have met at more remote locations. |

| 28th | 26–27 June 2002 | Canada | Jean Chrétien | Kananaskis, Alberta | [28] | Russia gains permission to officially host a G8 Summit. |

| 29th | 2–3 June 2003 | France | Jacques Chirac | Évian-les-Bains | The G8+5 was unofficially made, when China, India, Brazil, and Mexico were invited to this Summit for the first time. South Africa has joined the G8 Summit, since 2000, until the 2012 edition. Other first-time nations that were invited by the French president included: Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Switzerland.[21] | |

| 30th | 8–10 June 2004 | United States | George W. Bush | Sea Island, Georgia | [29] | A record number of leaders from 12 different nations accepted their invitations here. Amongst a couple of veteran nations, the others were: Ghana, Afghanistan, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey, Yemen and Uganda.[21] Also, the state funeral of former president Ronald Reagan took place in Washington during the summit. |

| 31st | 6–8 July 2005 | United Kingdom | Tony Blair | Gleneagles | [30] | The G8+5 was officially formed. On the second day of the meeting, suicide bombers killed 52 people on the London Underground and a bus. Nations that were invited for the first time were Ethiopia and Tanzania. The African Union and the International Energy Agency made their debut here.[21] During the 31st G8 summit in United Kingdom, 225,000 people took to the streets of Edinburgh as part of the Make Poverty History campaign calling for Trade Justice, Debt Relief and Better Aid. Numerous other demonstrations also took place challenging the legitimacy of the G8.[31] |

| 32nd | 15–17 July 2006 | Russia | Vladimir Putin | Strelna, St. Petersburg | First G8 Summit on Russian soil. Also, the International Atomic Energy Agency and UNESCO made their debut here.[21] | |

| 33rd | 6–8 June 2007 | Germany | Angela Merkel | Heiligendamm, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Seven different international organizations accepted their invitations to this Summit. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Commonwealth of Independent States made their debut here.[21] | |

| 34th | 7–9 July 2008 | Japan | Yasuo Fukuda | Toyako (Lake Toya), Hokkaido | [32] | Nations that accepted their G8 Summit invitations for the first time are: Australia, Indonesia and South Korea.[21] |

| 35th | 8–10 July 2009 | Italy | Silvio Berlusconi | La Maddalena (cancelled) L'Aquila, Abruzzo (re-located)[33] |

[1] | This G8 Summit was originally planned to be in La Maddalena (Sardinia), but was moved to L'Aquila as a way of showing Prime Minister Berlusconi's desire to help the region after the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake. Nations that accepted their invitations for the first time were: Angola, Denmark, Netherlands and Spain.[34] A record of TEN (10) international organizations were represented in this G8 Summit. For the first time, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the World Food Programme, and the International Labour Organization accepted their invitations.[35] |

| 36th | 25–26 June 2010[36] | Canada | Stephen Harper | Huntsville, Ontario[37] | [38] | Malawi, Colombia, Haiti, and Jamaica accepted their invitations for the first time.[39] |

| 37th | 26–27 May 2011 | France | Nicolas Sarkozy | Deauville,[40][41] Basse-Normandie | Guinea, Niger, Côte d'Ivoire and Tunisia accepted their invitations for the first time. Also, the League of Arab States made its debut to the meeting.[42] | |

| 38th | 18–19 May 2012 | United States | Barack Obama | Chicago (cancelled) Camp David (re-located)[43] |

The summit was originally planned for Chicago, along with the NATO summit, but it was announced officially on 5 March 2012, that the G8 summit will be held at the more private location of Camp David and at one day earlier than previously scheduled.[44] Also, this is the second G8 summit, in which one of the core leaders (Vladimir Putin) declined to participate. This G8 summit concentrated on the core leaders only; no non-G8 leaders or international organizations were invited. | |

| 39th | 17–18 June 2013 | United Kingdom | David Cameron | Lough Erne, County Fermanagh[45] | [2] | As in 2012, only the core members of the G8 attended this meeting. The four main topics that were discussed here were trade, government transparency, tackling tax evasion, and the ongoing Syrian crisis.[46] |

| 40th | 4–5 June 2014 | Russia (cancelled) European Union (Belgium) |

Vladimir Putin (cancelled) Herman Van Rompuy (new) and José Manuel Barroso |

Sochi (cancelled) Brussels (re-located) |

G7 summit as an alternative meeting without Russia in 2014 due to association with Crimean crisis.[47] G8 summit did not take place in Sochi, Russia. G7 summit relocated to Brussels, Belgium.[48] | |

| 41st | 7–8 June 2015 | Germany | Angela Merkel | Schloss Elmau, Bavaria[49] | [3] | Summit dedicated to focus on the global economy as well as on key issues regarding foreign, security and development policy.[50] Global Apollo Programme was also on the agenda.[51] |

| 42nd | 26–27 May 2016[52][53] | Japan | Shinzō Abe | Shima, Mie Prefecture[54] | [4] | The G7 leaders aim to address challenges affecting the growth of the world economy, like slowdowns in emerging markets and drops in price of oil. The G7 also issued a warning on the United Kingdom that "a UK exit from the EU would reverse the trend towards greater global trade and investment, and the jobs they create and is a further serious risk to growth".[55] Commitment to an EU–Japan Free Trade Agreement |

| 43rd | 26–27 May 2017[56] | Italy | Paolo Gentiloni | Taormina, Sicily[57] | [5] | G7 leaders emphasized common endeavours: to end the Syrian crisis, to fulfill the UN mission in Libya and reducing the presence of ISIS, ISIL and Da'esh in Syria and Iraq. North Korea was urged to comply with UN resolutions, Russian responsibility was stressed for Ukrainian conflict. Supporting economic activity and ensuring price stability was demanded while inequalities in trade and gender were called to be challenged. It was agreed to help countries in creating conditions that address the drivers of migration: ending hunger, increasing competitiveness and advancing global health security.[58] |

| 44th | 8–9 June 2018 | Canada[59] | Justin Trudeau | La Malbaie, Québec | ||

| 45th | TBD, 2019 | France[60] | Emmanuel Macron | TBD | ||

| 46th | TBD, 2020 | United States[60] | Donald Trump | TBD | ||

| 47th | TBD, 2021 | United Kingdom[citation needed] | Theresa May | TBD |

Leaders

| Member | Head of government | Finance minister | Central bank governor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | Prime Minister | Justin Trudeau | Minister of Finance | Bill Morneau | Stephen Poloz | |||

| France | President | Emmanuel Macron | Minister of the Economy | Bruno Le Maire | François Villeroy de Galhau | |||

| Prime Minister | Édouard Philippe | |||||||

| Germany | Chancellor | Angela Merkel | Minister of Finance | Wolfgang Schäuble | Jens Weidmann | |||

| Italy | Prime Minister | Paolo Gentiloni | Minister of Economy and Finance |

Pier Carlo Padoan | Ignazio Visco | |||

| Japan | Prime Minister | Shinzō Abe | Minister of Finance | Tarō Asō | Haruhiko Kuroda | |||

| United Kingdom | Prime Minister | Theresa May | Chancellor of the Exchequer | Philip Hammond | Mark Carney | |||

| United States | President | Donald Trump | Secretary of the Treasury | Steven Mnuchin | Janet Yellen | |||

| European Union | Council President[61] | Donald Tusk | Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs and the Euro |

Jyrki Katainen | Mario Draghi | |||

| Commission President[61] | Jean-Claude Juncker | |||||||

Heads of State and Government and EU representatives, as of 2017

Member country data

| Member | Trade mil. USD (2014) | Nom. GDP mil. USD (2014)[62] | PPP GDP mil. USD (2014)[62] | Nom. GDP per capita USD (2014)[62] | PPP GDP per capita USD (2014)[62] | HDI (2015) | Population (2014) | Permanent members of UN Security Council | DAC | OECD | Economic classification (IMF)[63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 947,200 | 1,785,387 | 1,595,975 | 50,304 | 44,967 | 0.913 | 35,467,000 | Advanced | |||

| France | 1,212,300 | 2,833,687 | 2,591,170 | 44,332 | 40,538 | 0.888 | 63,951,000 | Advanced | |||

| Germany | 2,866,600 | 3,874,437 | 3,748,094 | 47,774 | 46,216 | 0.916 | 80,940,000 | Advanced | |||

| Italy | 948,600 | 2,167,744 | 2,135,359 | 35,335 | 35,131 | 0.873 | 60,665 551 | Advanced | |||

| Japan | 1,522,400 | 4,602,367 | 4,767,157 | 36,222 | 37,519 | 0.891 | 127,061,000 | Advanced | |||

| United Kingdom | 1,189,400 | 2,950,039 | 2,569,218 | 45,729 | 39,826 | 0.907 | 64,511,000 | Advanced | |||

| United States | 3,944,000 | 17,348,075 | 17,348,075 | 54,370 | 54,370 | 0.915 | 318,523,000 | Advanced | |||

| European Union | 4,485,000 | 18,527,116 | 18,640,411 | 36,645 | 36,869 | 0.865 | 505,570,700 | — | — | — |

The G7 is composed of the wealthiest developed countries by national net wealth (See National wealth). The People's Republic of China, according to its data, would be the third-largest (9.1% of the world net wealth) in the world, but is excluded because the IMF and other main global institutions don't consider China a developed country.[64] As of 2014 Credit Suisse report the G7 (without the European Union) represents above 64% of the global net wealth.[64] Including the EU the G7 represents over 70% of the global net wealth.[64]

Member facts

- 7 of the 7 top-ranked advanced economies with the current largest GDP and with the highest national wealth (United States, Japan, Germany, UK, France, Italy, Canada).[65]

- 7 of the 15 top-ranked countries with the highest net wealth per capita (United States, France, Japan, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Germany).

- 7 of 10 top-ranked leading export countries.[66]

- 5 of 10 top-ranked countries with the largest gold reserves (United States, Germany, Italy, France, Japan).

- 7 of 10 top-ranked economies (by nominal GDP), according to latest (2016 data) International Monetary Fund's statistics.

- 5 countries with a nominal GDP per capita above US$40,000 (United States, Canada, Germany, United Kingdom, France).

- 4 countries with a sovereign wealth fund, administered by either a national or a state/provincial government (United States, France, Canada, Italy).[67]

- 7 of 30 top-ranked nations with large amounts of foreign-exchange reserves in their central banks.

- 3 out of 9 countries having nuclear weapons (France, UK, United States),[68][69] plus 2 countries that have nuclear weapon sharing programs (Germany, Italy).[70][71]

- 6 of the 9 largest nuclear energy producers (United States, France, Japan, Germany, Canada, UK), although Germany announced in 2011 that it will close all of its nuclear power plants by 2022.[72] Following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Japan shut down all of its nuclear reactors.[73] However, Japan restarted several nuclear reactors, with the refueling of other reactors underway.

- 7 of the 10 top donors to the UN budget for the 2016 annual fiscal year.

- 4 countries with a HDI index for 2013 of 0.9 and higher (United States, Germany, United Kingdom, Canada).

- 2 countries with the highest credit rating from Standard & Poor's, Fitch, and Moody's at the same time (Canada and Germany).[74]

- 3 countries are Constitutional Monarchies (United Kingdom, Canada, Japan), 2 are Presidential Republics (France, United States) and the other 2 are Parliamentary Republics (Germany, Italy)

Protests

In 2015, despite Germany's immense efforts to prevent it and despite the remote location of the summit, the luxury hotel Schloss Elmau at the foot of the Wetterstein mountains at an altitude of 1008 m above sea level, about 300 of the 7500 peaceful protesters led by the group 'Stop-G7' managed to reach the 3 m high and 7 km long security fence surrounding the summit location. The protesters questioned the legitimation of the G7 to make decisions that could affect the whole world. Authorities had banned demonstrations in the closer area of the summit location and 20,000 policemen were on duty in Southern Bavaria to keep activists and protesters from interfering with the summit.[75][76]

See also

- Big Four

- NATO Quint

- Group of Eight

- Group of 15

- G20

- Group of Thirty

- List of country groupings

- List of multilateral free-trade agreements

References

- ^ Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2013 (PDF). Credit Suisse. October 2013.

- ^ "IMF – International Monetary Fund Home Page".

- ^ a b c d "Evian summit – Questions about the G8". Ministère des Affaires étrangères, Paris.

- ^ Nicholas Bayne, Robert D. Putnam (2000). Hanging in There, Ashgate Pub Ltd, 230 pages, ISBN 075461185X

- ^ "Russia — Odd Man Out in the G-8", Mark Medish, The Globalist, 02-24-2006 Archived 5 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.Accessed: 7 December 2008

- ^ Bayne, Nicholas (7 December 1998), "International economic organizations : more policy making less autonomy", in Reinalda, Bob; Verbeek, Bertjan (eds.), Autonomous Policymaking By International Organizations (Routledge/Ecpr Studies in European Political Science, 5), Routledge, ISBN 9780415164863, OCLC 70763323, 0415164869

- ^ "G7/8 Ministerial Meetings and Documents". G8 Information Centre. University of Toronto. 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ International Money Fund. "Debt Relief Under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative;Perspectives on the Current Framework and Options for Change". IMF.org. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Van Houtven, Leo (September 2004). "Rethinking IMF Governance" (PDF). Finance & Development. International Money Fund. p. 18. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Bo Nielsen (14 April 2008). "G7 Statement Fails to Convince Major Traders to Change Outlook". Bloomberg L.P.

- ^ Simon Kennedy (10 October 2008). "G7 Against the Wall- Weighs Loan-Guarantee Plan (Update1)". Bloomberg L.P.

- ^ Yahoo.com Archived 16 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Grady, Sean (11 October 2008). "G7 pledges action to save banks". The Independent. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Statement by G7 Nations". G8 Info Ctr. University of Toronto. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "G7 leaders descend on the Netherlands for Ukraine crisis talks". CBC news. Thomson Reuters. 23 March 2014.

- ^ a b BBC (5 June 2014). "G7 leaders warn Russia of fresh sanctions over Ukraine". BBC.

- ^ Feldman, Adam (7 July 2008). "What's Wrong with the G-8". Forbes. New York.

- ^ Hajnal, Peter I. (1999). The G8 System and the G20: Evolution, Role and Documentation, p. 30., p. 30, at Google Books

- ^ a b Shabecoff, Philip. "Go-Slow Policies Urged by Leaders in Economic Talks; Closing Statement Calls for Sustained Growth Coupled With Curbs on Inflation; Ford's Aims Realized; 7 Heads of Government Also Agree to Consider a New Body to Assist Italy Co-Slow Economic Policies Urged by 7 Leaders," New York Times. 29 June 1976; Chronology, June 1976. Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Halifax G7 Summit 1995". Chebucto.ns.ca. 28 May 2000. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kirton, John. "A Summit of Substantial Success: The Performance of the 2008 G8"; page 88 and 89 G8 Information Centre – University of Toronto 17 July 2008.

- ^ "Denver Summit of the Eight". State.gov. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 12 December 1998. Archived from the original on 12 December 1998. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "1999 G8 summit documents". Web.archive.org. 26 February 2005. Archived from the original on 26 February 2005. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Kyushu-Okinawa Summit". MOFA. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Vertice di Genova 2001". Web.archive.org. 6 August 2001. Archived from the original on 6 August 2001. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Italy officials convicted over G8, BBC News, 15 July 2008

- ^ "UT G8 Info. Centre. Kananaskis Summit 2002. Summit Contents". G8.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Sea Island Summit 2004". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Special Reports | G8_Gleneagles". BBC News. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ David Miller "Spinning the G8" Archived 28 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Zednet, 13 May 2005.

- ^ "Hokkaido Toyako Summit – TOP". Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "BERLUSCONI PROPOSES RELOCATION OF G8 SUMMIT TO L'AQUILA". Running in heels. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "G8 Summit 2009 – official website – Other Countries". G8italia2009.it. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "G8 Summit 2009 – official website – International Organizations". G8italia2009.it. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "Canada's G8 Plans" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Prime Minister of Canada: Prime Minister announces Canada to host 2010 G8 Summit in Huntsville". Pm.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2010 Muskoka Summit". Canadainternational.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Participants at the 2010 Muskoka Summit. G8 Information Centre. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Le prochain G20 aura lieu à Cannes," Le point. 12 November 2010.

- ^ The City of Deauville Official 2011 G8 website. Retrieved 7 February 2011. Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kirton, John (26 May 2011). "Prospects for the 2011 G8 Deauville Summit". G8 Information Centre. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "2012 G8 Summit Relocation". G8.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "White House Moves G8 Summit From Chicago To Camp David". CBS Chicago. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "BBC News – Lough Erne resort in Fermanagh to host G8 summit". Bbc.co.uk. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "As it happened: G8 summit". BBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Russia out in the cold after suspension from the G8". The Scotsman. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "G-7 Agrees to Exclude Russia, Increase Sanctions/World Powers to Meet in Brussels in June Without Russia". The Wall Street Journal. 25 March 2014.

- ^ Germany to hold 2015 G8 summit at Alpine spa Elmau in Bavaria

- ^ "German G7 presidency – Key topics for the summit announced". 19 November 2014.

- ^ Carrington, Damian. "Global Apollo programme seeks to make clean energy cheaper than coal". The Guardian. No. 2 June 2015. Guardian News Media. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Japan announced to host G7 summit in 2016 in Shima". prepsure.com. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Japan Announces Dates for G7 Summit in 2016". NDTV. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "来年のサミット 三重県志摩市で開催へ (Next Year's Summit To Be Held in Shima City, Mie Prefecture)" (in Japanese). 5 June 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Asthana, Anushka (27 May 2016). "Brexit would pose 'serious risk' to global growth, say G7 leaders". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Renzi announces to host G7 summit in 2017 in Taormina". RaiNews24. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Redazione (1 April 2016). "G7 a Taormina, è ufficiale. Renzi chiama da Boston il sindaco Giardina: «Il vertice si farà nella Perla»".

- ^ "G7 Taormina Leaders' Communiqué" (PDF). G7 Italy 2017. 27 May 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Canada to host 2018 G7 Summit in Charlevoix, Quebec". pm.gc.ca. Prime Minister of Canada. 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b "G7 Summit in Brussels, 4 – 5 June 2014: Background note and facts about the EU's role and action". 3 June 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Van Rompuy and Barroso to both represent EU at G20". EUobserver.com. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2012. "The permanent president of the EU Council, former Belgian premier Herman Van Rompuy, also represents the bloc abroad in foreign policy and security matters...in other areas, such as climate change, President Barroso will speak on behalf of the 27-member club."

- ^ a b c d "Gross domestic product". IMF World Economic Outlook. October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook data". IMF. 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Global Wealth Databook 2014 Credit Suisse Research Institute, October 2014 Page: 33-92

- ^ "CIA World Fact Country Rankings".

- ^ "exports". cia factbook.

- ^ "Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings". SWF Institute. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "Status of Nuclear Forces". Federation of American Scientists. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Which countries have nuclear weapons?". BBC News. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Malcolm Chalmers; Simon Lunn (March 2010), NATO's Tactical Nuclear Dilemma, Royal United Services Institute, retrieved 16 March 2010

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Der Spiegel: ''Foreign Minister Wants US Nukes out of Germany'". Der Spiegel. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Germany: Nuclear power plants to close by 2022". BBC. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Tomari shutdown leaves Japan without nuclear power". BBC News. 5 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "11 countries with perfect credit". USA Today. 16 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Der Spiegel: Proteste um Schloss Elmau – Demonstranten wandern bis zum G7-Zaun". Der Spiegel. 7 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Bild: 7 Kilometer lang, 3 Meter hoch, auf ganzer Länge beleuchtet". Bild. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.