Dante Symphony

A Symphony to Dante's Divine Comedy, S.109, or simply the "Dante Symphony", is a program symphony composed by Franz Liszt. Written in the high romantic style, it is based on Dante Alighieri's journey through Hell and Purgatory, as depicted in The Divine Comedy. It was premiered in Dresden in November 1857, with Liszt himself conducting, and was unofficially dedicated to the composer's friend and future son-in-law Richard Wagner. The entire symphony takes approximately 45 minutes to perform.

Some critics have argued that the Dante Symphony is not so much a symphony in the classical sense as it is two descriptive symphonic poems.[1] Regardless, Dante consists of two movements, both in a loosely structured ternary form with little use of thematic transformation.[2]

Composition

Liszt had been sketching themes for the work since the early 1840s,[3] and in 1847 he played some fragments on the piano for his Polish mistress Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. At this early stage in the composition it was Liszt's intention that performances of the work be accompanied by a slideshow depicting scenes from the Divine Comedy by the artist Bonaventura Genelli.[4] He also planned to use an experimental wind machine to recreate the winds of Hell at the end of the first movement. Although Princess Carolyne was willing to defray the costs, nothing came of these ambitious plans and the symphony was set aside until 1855.[5]

In June 1855 Liszt resumed work on the symphony and had completed most of it before the end of the following year. Thus, work on the Dante Symphony roughly coincided with work on Liszt's other symphonic masterpiece, the Faust Symphony, which was inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's drama Faust. For this reason, and because they are the only symphonies Liszt ever composed (though certainly not his only symphonic works), the Dante and Faust symphonies are often recorded together.

In October 1856 Liszt visited Richard Wagner in Zürich and performed his Faust and Dante symphonies on the piano. Wagner was critical of the Dante Symphony's fortissimo conclusion, which he thought was inappropriate as a depiction of Paradise. In his autobiography he later wrote:

If anything had convinced me of the man's masterly and poetical powers of conception, it was the original ending of the Faust Symphony, in which the delicate fragrance of a last reminiscence of Gretchen overpowers everything, without arresting the attention by a violent disturbance. The ending of the Dante Symphony seemed to me to be quite on the same lines, for the delicately introduced Magnificat in the same way only gives a hint of a soft, shimmering Paradise. I was the more startled to hear this beautiful suggestion suddenly interrupted in an alarming way by a pompous, plagal cadence which, as I was told, was supposed to represent St Dominic.

"No!" I exclaimed loudly, "not that! Away with it! No majestic Deity! Leave us the fine soft shimmer!"[6]

Liszt agreed and explained that such had been his original intention, but he had been persuaded by Princess Carolyne to end the symphony in a blaze of glory. He rewrote the concluding measures, but in the printed score he left the conductor with the option of following the pianissimo coda with the fortissimo one.[7]

Liszt's original intention was to compose the work in three movements: an Inferno, a Purgatorio and a Paradiso. The first two were to be purely instrumental, and the finale choral.[8] Wagner, however, persuaded Liszt that no earthly composer could faithfully express the joys of Paradise.[9] Liszt dropped the third movement but added a choral Magnificat at the end of the second movement. This action, some critics claim, effectively destroyed the work's balance, leaving the listener, like Dante, gazing upward at the heights of Heaven and hearing its music from afar.[10] Moreover, Liszt scholar Humphrey Searle argues that while Liszt may have felt more at home portraying the infernal regions than the celestial ones, the task of portraying Paradise in music would not have been beyond his powers.[11]

Liszt put the final touches to the symphony in the autumn of 1857. The premiere of the work took place at the Hoftheater in Dresden on 7 November 1857. The performance was an unmitigated disaster due to inadequate rehearsal; Liszt, who conducted the performance, was publicly humiliated.[12] Nevertheless, he persevered with the work, conducting another performance (along with his symphonic poem Die Ideale and his second piano concerto) in Prague on 11 March 1858. Princess Carolyne prepared a programme for this concert to help the audience follow the unusual form of the symphony.[13]

Like his symphonic poems Tasso and Les préludes, the Dante Symphony is an innovatory work, featuring numerous orchestral and harmonic advances: wind effects, progressive harmonies that generally avoid the tonic-dominant bias of contemporary music, experiments in atonality, unusual key signatures and time signatures, fluctuating tempi, chamber-music interludes, and the use of unusual musical forms. The Symphony is also one of the first to make use of progressive tonality, beginning and ending in the radically different keys of D minor and B major, respectively, anticipating its use in the symphonies of Gustav Mahler by forty years.

Liszt was not the only symphonic composer who was inspired by Dante's Commedia. In 1863 Giovanni Pacini composed a four-movement Sinfonia Dante (the finale depicts Dante's triumphant return to Earth).

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for one piccolo (doubling as 3rd flute in the second movement), two flutes, two oboes, one English horn, two clarinets in B♭ and A, one bass clarinet in B♭ and A, two bassoons, four horns in F, two trumpets in B♭ and D, two tenor trombones, one bass trombone, one tuba, two sets of timpani (requiring two players), cymbals, bass drum, tamtam, two harps (the second harp only in the second movement),[14] strings, harmonium (second movement only), and a women's choir comprising soprano and alto singers (second movement only), one of the sopranos being required to sing a solo.[15]

Inferno

The opening movement is entitled Inferno and depicts Dante's and Virgil's passage through the nine Circles of Hell. The structure is essentially sonata form,[16] but it is punctuated by a number of episodes representing some of the salient incidents of the Inferno. The longest and most elaborate of these – the Francesca da Rimini episode from Canto 5 – lends the movement something of the structure of a triptych.[17]

The music is chromatic and tonally ambiguous; although the movement is essentially in D minor, this is often negated by G♯, which is as far as one can get from D. There are relatively few authentic cadences or key signatures to help resolve the tonal ambiguity. The harmony is based on sequences of diminished sevenths, which are often not resolved.

The Gates of Hell

The movement opens with a slow introduction (Lento) based on three recitative-like themes,[18] which Liszt has set to four of the nine lines inscribed over the Gates of Hell:

Per me si va nella città dolente, |

Through me is the way to the sorrowful city, |

1 |

The first of these themes, which is immediately repeated in a slightly varied form, begins in D minor – a key Liszt associated with Hell[19] – but ends ambiguously on G♯ a tritone higher. This interval is traditionally associated with the Devil, being known in the Middle Ages as diabolus in musica:[20]

The second theme is closely related to the first, but this time there is an unambiguous authentic cadence on G♯:

The third theme begins as a chantlike monotone played by horns and trumpets on E♮ against a string tremolo in C♯ minor. It cadences on a tonally ambiguous diminished seventh on G♯:

The first and third of these themes are punctuated by an important drum-roll motif played on two timpani and the tam-tam, which recurs in various forms throughout the movement:

As the tempo increases, a motif derived from the first of these themes is introduced by the strings. This Descent motif depicts Dante and Virgil's descent into Hell:

This is accompanied by another motif based on rising and falling semitones (appoggiature), which is also derived from the symphony's opening theme, while the horns play the third theme in augmentation on G♯:

This passage is punctuated by a brass motif taken from the third theme:

These motifs are developed at length as the tempo gradually increases and the tension builds. The music is dark and turbulent. The chromatic and atonal nature of the material conveys a sense of urgency and growing excitement.

The Vestibule and First Circle of Hell

At the climax of this accelerando, the tempo becomes Allegro frenetico and the time signature changes from common time to Alla breve: the slow introduction comes to an end and the exposition begins. The first subject, which is introduced by the violins, is based on the same rising and falling semitones that we heard in the introduction. Ostensibly it begins in D minor, but the tonality is ambiguous:

The tempo increases to Presto molto and a second subject is played by wind and strings over a pedal on the dominant A:

Although Liszt provides no verbal clues to the literary associations of these themes, it seems reasonable to assume that the exposition and ensuing section represent the Vestibule (in which the dead are condemned to perpetually chase after a whirling standard) and First Circle of Hell (Limbo), which Dante and Virgil traverse after they have passed through the Gates of Hell.[citation needed] It is even possible that the transition between the two subjects represents the river Acheron, which separates the Vestibule from the First Circle: on paper the figurations are reminiscent of those Beethoven uses in the Scene by the Brook in his Pastoral Symphony, though the aural effect is quite different.[citation needed]

The following development section explores both subjects at length, but motifs from the introduction are also developed. The second subject is heard in B major.[21] The descent motif reasserts itself as Dante and Virgil descend deeper into Hell. The music reaches a great climax (molto fortissimo); the tempo reverts to the opening Lento, and the brass intone the Lasciate ogni speranza theme from the slow introduction, accompanied by the drum-roll motif. Once again Liszt inscribes the score with the corresponding words of the Inferno.

The Second Circle of Hell

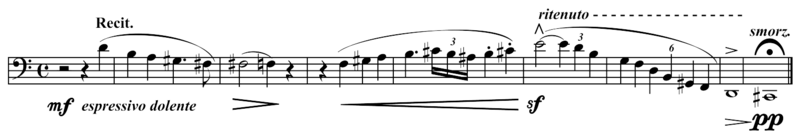

As Dante and Virgil enter the Second Circle of Hell, rising and falling chromatic scales in the strings and flutes conjure up the infernal Black Wind that perpetually buffets the damned.[22] The music grinds to a halt, and quiet drum beats lead to silence. An episode in 5/4 time marked Quasi Andante, ma sempre un poco mosso ensues, beginning with harp glissandi and chromatic figurations in strings and woodwind that once again invoke the swirling wind.[23] After a pause, however, the bass clarinet intones an expressive recitative, which takes the instrument to the very bottom of its range:

This theme is then taken up and extended by a pair of clarinets, accompanied by the same harp glissandi and chromatic figures that opened the section. After a restatement a fourth higher by the bass clarinet, the recitative is played by the cor anglais and this time Liszt sets the music to the words of Francesca da Rimini, whose adulterous affair with her brother-in-law Paolo cost her both her life and her soul:

.... Nessun maggior dolore |

.... There is no greater sorrow |

121 |

After a brief passage based on a theme derived from the recitative, there ensues an episode marked Andante amoroso. The tragic love of Francesca and Paolo is depicted at length by a passionate theme in 7/4 time, which is also based on the recitative.[24]

Curiously, the key signature suggests F♯ major, a key Liszt often reserved for divine or beatific music.[19] The theme actually begins in D♯ minor, passing sequentially through F♯ minor and A minor. Two unmuted violins are contrasted with the rest of the violins, which are muted.

The Seventh Circle of Hell

As before, the transition to the next circle of Hell is prefaced by a return of the Lasciate ogni speranza theme. A short cadenza for harp, continuing the Black Wind motif, leads to a passage which Liszt marks with the following note: This entire passage is intended to be a blasphemous mocking laughter.... In the Inferno Dante meets the blasphemous Capaneus in the Seventh Circle of Hell (Canto 14).[25] The dominant motifs – triplets, trills and falling seconds – have all been heard before.

The time signature reverts to Alla breve, the key signature is cancelled, and the tempo quickens to Tempo primo in preparation for the ensuing recapitulation.

Recapitulation

The first subject is recapitulated in augmentation, but where before it represented the sufferings of the damned, now it is a cruel parody of that suffering in the mouths of their attendant devils.[26] The tempo quickens and the music reaches a climax; the second subject is recapitulated with little alteration from the exposition. Presumably the recapitulation represents the Eighth and Ninth Circles of Hell.[27]

Coda

Another climax leads into the coda. The final pages of the movement are dominated by the descent motif and the second subject. After a climax, the music comes to a momentary pause. The descent motif quickly builds up to an even greater climax (molto fortissimo). In the final ten measures, however, the Lasciate ogni speranza theme returns for the last time: Dante and Virgil emerge from Hell on the other side of the world. The movement ends in D, though there is no conventional authentic cadence. The tonal ambiguity which has coloured the movement from the beginning is maintained to the very last measure.[28]

Purgatorio

The second movement, entitled Purgatorio, depicts Dante and Virgil's ascent of Mount Purgatory. It is Ternary in structure. The first section is solemn and tranquil and in two parts; in the second section, which is more agitated and lamentable, a fugue is built up to a grand climax; in the final section there is a return to the mood of the opening, the principal themes of which are recapitulated. This tripartite structure reflects the architecture of Dante's Mount Purgatory, which can also be divided into three parts: the two terraces of Ante-Purgatory, where the excommunicate and the late repentant expiate their sins; the seven cornices of Mount Purgatory proper, where the Seven Deadly Sins are expiated; and the Earthly Paradise at the summit, from which the soul, now purged of sin, ascends to Paradise.[29]

Ante-Purgatory

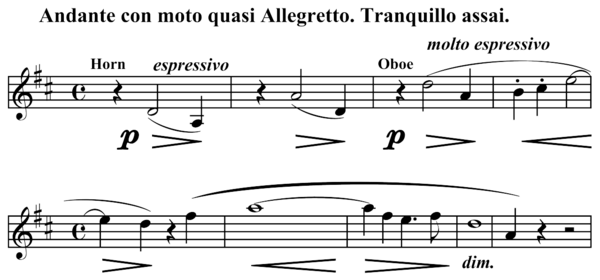

The movement opens in D major in a slow tempo (Andante con moto quasi Allegretto. Tranquillo assai). A solo horn introduces the opening theme to the accompaniment of rocking chords on muted strings and arpeggiated triplets played by the harp. This theme is taken up by the woodwind and horns, and after twenty-one measures dies away against a shimmering haze of rising and falling arpeggios on the harp:

This whole section is then repeated in E♭ (though the key signature is altered from D major to B♭). This tranquil episode represents perhaps the excommunicate, who inhabit the first terrace of Ante-Purgatory.

The tempo then changes to Più lento and the key signature reverts to D major. The cellos introduce a new theme, which is quickly passed to the first violins:

As it too dies away like the opening theme, it gradually metamorphoses into a chorale-like theme in F♯ minor, which is solemnly intoned by horns and woodwind in a slower tempo (un poco meno mosso):

This is developed at length, being joined in counterpoint with a variant of the second theme. The music finally dies away and silence ensues, bringing this opening section to a close in B minor. The second terrace of Ante-Purgatory is inhabited by the late repentant. In Canto 7 there is a celebrated description of evening in a beautiful valley where the penitents sing the Salve Regina; this passage may have inspired Liszt's chorale-like theme.

The Seven Cornices of Mount Purgatory

The second section of the movement is marked Lamentoso and its agonizing figurations are in marked contrast to the beatific music of the opening section. The muted violas introduce the principal theme, which comprises a series of agitated fragments in B minor. The music graphically reflects the pleading and suffering of the penitents before it breaks up into flowing triplets:[30]

This theme is taken up by the other strings and a five-part fugue ensues. The woodwind add their pleas (dolente), and the music becomes louder and more agitated (gemendo). The horns join the fugue as it reaches its climax, at which point the music disintegrates into fragments and grows softer; but it soon finds its voice again and is worked up into a huge climax in F minor for full orchestra (grandioso) that is strikingly reminiscent of the opening movement of Berlioz's Requiem:

This liberating[31] climax takes us through a series of sequences from F minor through G♭ minor and G minor to E♭ major. A brief transition ensues in which staccato triplets in the cellos and double basses are answered by static chords in the stopped horns and woodwind.

The key signature reverts to D major. The triplets, now played legato on the violins, are accompanied by passionate figures in the woodwind (gemendo, dolente ed appassionato) and muted chords in the horns. The music fades away and the cellos bring things to a standstill.

The Earthly Paradise

After a long pause the chorale from the opening section is recapitulated in augmentation, accompanied by string pizzicati. The Più lento theme from the opening section is heard once again, and both themes are briefly alternated. Two harps take up the triplets and the concluding strain of the movement's opening theme returns. The music modulates from B♭ major to B major, and passes without a break to the final chorus.

Magnificat

The symphony concludes with a short setting for female or boys' choir of the first two lines of the Magnificat, culminating in a series of Hosannas and Hallelujahs:

Magnificat anima mea Dominum, |

My soul magnifies the Lord, |

Curiously, the Magnificat is not mentioned anywhere in the Commedia; nor is there any Hallelujah;[32] the Hosanna, however, is heard both in the Earthly Paradise of the Purgatorio and in the Paradiso.

In the score, Liszt directs that the choir be hidden from the audience:

The female or boys' choir is not to be placed in front of the orchestra, but is to remain invisible together with the harmonium, or in the case of an amphitheatrical arrangement of the orchestra, is to be placed right at the top. If there is a gallery above the orchestra, it would be suitable to have the choir and harmonium positioned there. In any case, the harmonium must remain near the choir.

The time signature changes to a combination of 6/4 and 2/3. The choir intones the words against a shimmering backdrop of divided strings, rocking figurations in the woodwind and arpeggios played by two harps.

The tempo quickens and the music becomes gradually louder as the time signature changes to 9/4 or 3/3. The choir sings triumphantly of God my saviour.

The tempo drops to Un poco più lento, a solo trumpet call dies away to silence, after which a solo voice sings the opening line of the Magnificat in B major.[33]

The whole orchestra resounds with the same phrase. After another brief silence, the choir sings a chorale to the second line of the Magnificat, accompanied by a solo cello, bassoons and clarinets.

In the triumphant coda the divided chorus sings Hosanna and Hallelujah in a series of carefully crafted modulations, which reflect Dante's ascent sphere-by-sphere towards the Empyrean; this is in marked contrast to the first movement, where key shifts were sudden and disjointed.[34] As the Hosannas descend step by step from G♯ down to C, the Hallelujahs rise from G♯ up to F. The whole chorus then joins together in a final, triumphant Hallelujah on the dominant F♯. In this passage, the bass steps down the whole-tone scale from G♯ to A♯. Liszt was proud of this innovatory use of the whole-tone scale, and mentions it in a letter to Julius Schäffer, the music director of the Schwerin orchestra.[35]

The orchestra concludes with a quiet plagal cadence in B major; the timpani add a gentle authentic cadence of their own. The work ends molto pianissimo.

The second ending, which follows rather than replaces the first ending, is marked Più mosso, quasi Allegro. The ppp of the first ending gives way to ff. Majestic trumpets and trombones – accompanied by rising scales in the strings and woodwind, and by chords in the horns, harps, harmonium and strings – set the scene for a reappearance of the women's chorus. Three repetitions of a single word, Hallelujah, bring the work to a towering conclusion with a plagal cadence in B major.

Critical reception

George Bernard Shaw, reviewing the work in 1885, criticized it heavily, complaining that the manner in which the program was presented by Liszt could just as well represent "a London house when the kitchen chimney is on fire". He then notes that the symphony is "extremely loud", mentioning the fortissimo trombones, that later repeat at fff.[36] On the other hand, James Huneker called the work "the summit of his creative power and the ripest fruit of that style of programme music".[37]

See also

References

- ^ Ewen, 517.

- ^ Temperley, New Grove, 18:460.

- ^ In February 1839 he noted in his Journal des Zyi: "I will attempt a symphonic composition based on [Dante's Divine Comedy]." See Kenneth Hamilton (2005), p.219.

- ^ A performance with slideshow was eventually given in Brussels in 1984. See Derek B. Scott (2003), p. 140.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), p. 50. Here Walker writes that the symphony was "shelved until 1856", but on page 260 he writes that work on the symphony was resumed in June 1855.

- ^ Richard Wagner, Mein Leben.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), pp. 409–410; Richard Wagner (1857).

- ^ Correspondence of Wagner and Liszt, Volume 2, Letter 189, 2 June 1855.

- ^ Correspondence of Wagner and Liszt, Volume 2, Letter 190, 7 June 1855.

- ^ Searle, New Grove, 11:45. As Liszt originally intended the Paradiso movement to be choral, it is not at all certain to what extent the final outcome was due to Wagner's intervention: the Magnificat is choral and is clearly meant to be a depiction of Dante's Paradiso.

- ^ Searle, "Orchestral," 310–11. It could be argued that this is precisely what Liszt has done in the Magnificat.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), p. 296.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), p. 317 and pp. 488–489.

- ^ In the full score Liszt sanctions the use of a pianoforte "in the absence of harp".

- ^ In the full score Liszt calls for Frauenchor. Frauen- oder Knabenstimmen, "Female chorus. Female or boys' voices." He also requests that the harmonium and choir be invisible to the audience.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), pp. 151–152.

- ^ M. D. Calvocoressi, The Musical Times, Volume 66, No. 988 (1 June 1925), pp. 505–507.

- ^ Derek B. Scott (2003), p. 134.

- ^ a b Alan Walker (1989), p. 154n.

- ^ This theme has been compared to the subject of the Fugue in C Major from Book One of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier: Ashton Ellis, William (1908). "IV". Life of Richard Wagner. Vol. 6. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd. p. 166. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

just as the subject of the first fugue in the Wohltemperirte is mendelsified into the introduction of the Dante symphony.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982) identifies this with the defiance of Capaneus (Canto 14) and Vanni Fucci (Canto 24), whom Dante encounters in the Seventh and Eighth Circles respectively.

- ^ Inferno, Canto 5, lines 25–51.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), p. 316.

- ^ It was at this point during a rehearsal of the symphony that Liszt turned to the strings and said, Mehr blau, meine Herren! ("Bluer, gentlemen!"). See Alan Walker (1989), p. 278:

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 158, identifies this passage with the band of sneering and obscene devils who provide an escort for Dante and Virgil in the Eighth Circle (Cantos 21 and 22). He also mentions Liszt's use here of the contrabassoon, though no such instrument appears in the Breitkopf & Härtel score.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 158.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 152, identifies this section as representative of the sneering devils in the Eighth Circle (Cantos 21 and 22) and the sight of Lucifer in the Ninth Circle (Canto 34).

- ^ According to Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 158, the final open fifths denote Lucifer's impotence.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 159, suggests that the Purgatorio movement makes no attempt to depict Dante's journey in strict chronological order, presenting instead contrasting aspects of the penitents' hopes and sufferings.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barricelli (1982) suggests that the liturgical music of the first part represents the collective suffering of the penitents, while the "introspective fugue" suggests individual meditation on one's sins.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 162.

- ^ In the Inferno 12:88, Virgil refers to Beatrice as one who briefly left off her singing of the Hallelujah in order to visit him.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barracelli (1982), p. 163, suggests that this is the voice of Beatrice.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Barricelli (1982), pp. 155 and 164.

- ^ Alan Walker (1989), p. 324.

- ^ Shaw, Bernard (1978). The great composers: reviews and bombardments. University of California Press. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-0-520-03266-8.

- ^ Garvin, Harry Raphael (1981). Literature, arts, and religion. Bucknell University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8387-5021-6.

Bibliography

- Barricelli, Jean-Pierre (1982). Liszt's Journey Through Dante's Hereafter. Bucknell Review. Vol. 26: Literature, Arts and Religion. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 149–166. ISBN 9780838750216.

- Calvocoressi, M. D. (1925). "Liszt's 'Dante' Symphony and Tone Poems." The Musical Times 66 (988): 505–507.

- ed. Ewen, David, The Complete Book on Classical Music (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1965). Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 65-11033

- Hamilton, Kenneth (2005). The Cambridge Companion to Franz Liszt. Cambridge University Press.

- Pohl, Richard (1883). Franz Liszt: Studien und Erinnerungen. Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ed Sadie, Stanley, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, First Edition (London: Macmillan, 1980). ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- MacDonald, Hugh, "Symphonic poem"

- Searle, Humphrey, "Liszt, Franz"

- Temperley, Nicholas, "Symphony (II)"

- ed Sadie, Stanley, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001). ISBN 0-333-60800-3

- Walker, Alan, "Liszt, Franz"

- Scott, Derek B. (2003). From the Erotic to the Demonic: On Critical Musicology. Oxford University Press.

- Searle, Humphrey. "Franz Liszt" in The Symphony, Volume One: Haydn to Dvorak. Ed. Robert Simpson. 3 Vols. London, UK: Redwood Press Limited, 1972. 262–274. ISBN 0-7153-5523-6

- ed. Walker, Alan, Franz Liszt: The Man and His Music (New York: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1970). SBN 8008-2990-5

- Searle, Humphrey, "The Orchestral Works"

- Walker, Alan (1989). Franz Liszt. Vol. 2. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-17215-6.

External links

- Dante Symphony, full score and parts (Liszt, S.109): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Dante Symphony, 2 piano arrangement (Liszt, S.648): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Franz Liszt's Dante Symphony Analysis and description of Franz Liszt's Dante Symphony

- A Symphony to Dante Description of the symphony