User:Byronmercury/sandbox

The politics of Friedenstag

"A work extolling the union of peoples."

"This work in which I put the best of myself."[1]

Strauss rarely got involved in political matters: in 1914 he had refused to join the war-hysteria and did not sign up to the Manifesto of German Artists in support of the war effort, declaring that “Declarations about war and politics are not fitting for an artist, who must give his attention to his creations and his works”.[2] However, with Friedenstag, he made an exception, perhaps out of loyalty to Zweig, or perhaps due to his growing dislike of the Nazi regime. Both Zweig and Strauss shared a common opposition to the militarism and anti-Semitism of the Nazis. Musicologist Pamela Potter argues that Zweig and Strauss constructed an opera whose surface aesthetic was acceptable to the Nazis, but had within it a clear pacifist and humanist message. It was an opera dealing with German history (the end of the thirty years war in 1648), with the central character of a commandant who appealed to the Nazi ideal of the loyal and dedicated soldier. “The message of peace thus shone through the masquerade of a National Socialist work”. [3] Foreign reviewers were able to see more clearly the essentially pacifist and humanitarian nature of the work.

The pacifist perspective is put into the mouths of the Mayor and townspeople who come to beg the commander to surrender. The townspeople express the hopelessness and desolation of war:

Tell him what war is,

The murderer of my children!

And my children are dead,

And the old folk whimper for food.

In the wreck of our houses

We must go hunting Foul rats to feed us.

The Mayor likewise:

Whom do you hope to defeat?

I’ve seen the enemy, they’re men like us

they’re suffering out there in their

trenches, just as we are.

When they tread they groan like us –

and when they pray, they pray like us to God!

Zweig’s skill as a librettist is shown by his having the soldiers describe the approaching “rabble” of townspeople using the Nazi terminology used to denigrate Jews such as “rats” and “enemy within”:[4]

There’s a few grey rats swarming.

Two thousand, three thousand, storming the gate!

From the town!

The enemy? Trouble.

The enemy within. Arm yourselves!

Who wastes powder on rats?

The opera was performed many times in Germany, Austria and Italy and its popularity stemmed from the fact that it allowed people to openly express the preference for peace over war in a politically acceptable and safe way. Performances were only halted after was well under way. Strauss himself was surprised at the acceptance of the opera by the Nazis. He wrote “I fear that this work in which I put the best of myself will not be performed much longer. Will the cataclysm which we all fear soon break out?”[5] Part of the reason the Nazis were willing to allow its performance was no doubt to reinforce the image their propaganda was seeking to promote that Germany did not want war. The premier was just after the Anschluss when Austria was annexed by Germany and a few weeks before the signing of the Munich agreement between Germany, Britain, France and Italy, hailed as “peace in our time” by the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlin. Adolf Hitler and many leading Nazi figures attended the opera in June 1939 in Vienna, when plans for the invasion of Poland a few months later would have been well under way.

Friedenstag was premiered a few months before the Kristallnacht atrocities on 9-10 November 1938. On November 15th, Strauss rushed back from Italy to Garmisch because his wife Pauline had telegraphed him to return because his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice was under house arrest. Strauss managed to obtain her release, but from then on the position of Alice and grandchildren Christian and Richard became perilous. In December 1941, Strauss moved to Vienna, where the Nazi governor Baldur von Schirach was an admirer of Strauss and offered some protection. Strauss was to experience at close quarters what was happening to Alice’s family. In 1942, Strauss became involved in the attempts of his son France to get Jewish relatives out to Switzerland, including an ill-fated visit to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt. Many of Alice's relatives died in the holocaust. Son Franz and Alice were put under house arrest in Vienna in 1943. The position of Alice and her children was never without fear. Zweig’s books had been banned and burned soon after the Nazis came to power and he spent most of his time in London. On the verge of becoming a permanent resident, with the outbreak of war he suddenly became an enemy alien and had to give up his dream of living in Britain. He moved to the US and then Brazil. Depressed by the growth of intolerance, authoritarianism, and Nazism, feeling hopeless for the future for humanity, he committed suicide with his wife on February 23, 1942.

Recordings of Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss was recorded many times later in his life. The earliest recordings were of him as a pianist in 1905, and the last recordings were of him conducting in 1949 weeks before his death. Most of the recordings were made of him conducting orchestras in Germany, Austria, America, Great Britain and Switzerland. There were also recordings of him accompanying singers in performances of his songs.

Piano Rolls 1905-6

The very first recordings were recordings of Strauss playing the piano made using piano rolls in 1905-6. According to Peter Morse, the following recordings were made issued by Welte Mignon, probably recorded in Freiburg in late 1905 or 1906. There were some piano rolls made in 1914 on the Hupfield system, which was inferior to the Walte Mignon in terms of providing an authentic record of how the piano was played.

| work(s) recorded | Where and when recorded | Currently available recording. |

|---|---|---|

| Salome's Waltz, Salome Fragments. | Probably Freiburg 1906 | DS 2006 |

| Feuersnot, Love scene. | Probably Freiburg 1906 | DOC 2010 |

Stimungsbuilder, Opus 9.

|

Probably Freiburg 1906 | DOC 2010 |

Stimungsbuilder, Opus 9.

|

Probably Freiburg 1906 | Currently unavailable |

| Ein Heldenleben, Love scene. | Currently unavailable. |

First Orchestral Recordings: Berlin 1916

The first recordings made by Strauss were with the Konigliche Kapelle in Berlin on 5-7th December 1966, recorded acoustically by Deutsche Gramophone. The recordings were issued as 78 rpm records.

| work(s) recorded | Currently available recording. |

|---|---|

Das Burger als Edelmann (1912).

|

DS 2006 |

Currently available CDs and downloads

There are many available recordings of Richard Strauss performing. Some of the larger collections include:

| CD Title. | Date of release | Description | Label | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strauss Conducts Strauss | 1991 | 3 CDs of recordings of orchestral works from 1926-1941. | Deutsche Grammophon Dokumente DG 429 925-2 | DG 1991 |

| Strauss conducts Strauss, Beethoven and Mozart. | 2014 | 1991 enlarged to 7 CDs with recordings of Strauss conducting other composers and accompanying some songs. | Deutsche Grammophon DG 002037802 | DG 2014 |

| Richard Strauss: composer, conductor, pianist and accompanist Vol.1-10. | 2010 | 10 CDs of Songs, piano and orchestral music from 1905-1944 | Documents 291371-291380. | DOC 2010 |

| Richard Strauss: The complete British and American recordings 1921-26. | 2009 | 1 CD | Pristine PASC 175 | P 2009

|

| Richard Srauss conducts Richard Strauss in acoustic and electrical recordings from 1916-1927 | 2014 | 3 CDs of recordings (German, British and American). Bonus 1949 recording the last Strauss appearance as conductor. | Classical Recordings Quarterly Editions CRQ CD 155-156-157. | CRQ 2014 |

| Masters of the Piano Roll | 2006 | 1 CD, includes three early Welte Mignon recrodings from 1906. | DAL SEGNO DSPRCD010 | DS 2006 |

| Richard Strauss: Duett Concertino etc. (2015) | 2016 | CD includes Strauss conducting 4 songs in 1947. | CPO 7779902 | CPO 2016 |

External resources

Anthony Holden (2011): Richard Strauss: A musical life. Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12642-6.

Peter Morse (1977). RICHARD STRAUSS' RECORDINGS: a complete discography, Journal of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, volume 9:1, pages 5-65. There were also a supplement to the original article published in 1979 volume 10:2.

Carsten Schmidt (2014). Richard Strauss and the recorded media. Classical Recordings Quarterly.

Old

Duett concertino for Clarinet and Bassoon in F for string orchestra and Harp

| Symphony in F Minor | |

|---|---|

| Symphony by Richard Strauss | |

| File:Richard strauss Richard Strauss the year after the premiere of the F minor Symphony. | |

| Key | F Minor |

| Catalogue | Opus 12, TrV 126. |

| Composed | 1885. |

The Duett concertino for Clarinet and Bassoon in F for string orchestra and Harp (TrV 293) was written by Richard Strauss in 1946-7 and premiered in 1948. It is the last purely instrumental work he wrote.

Composition history

The first mention of the Duett-concertino in Strauss's notebook is 15 December 1946 when he was at Baden. He mentioned working on it again in September 1947 when at Pontresina, finishing the score on 16th December 1947 when he was in Montreux. [6] The concerto was written with an old friend in mind: Professor Hugo Burghauser, who had been the principal bassoonist with the Vienna Philharmonic but had since emigrated to New York. The score published by Boosey and Hawkes in 1949 has the dedication to Burghauser. Strauss had written to him in 1946:

I am very busy with an idea for a double concerto for clarinet and bassoon thinking especially of your beautiful tone - evertheless, apart from a few sketched out themes it still remains no more than an intention. Perhaps it would interest you.

The score may have an underlying program for the first movement. When the concerto was completed, Strauss wrote again to Burghauser joking that

A dancing princess is alarmed by the grotesque cavorting of a bear in imitation of her. At last she is won over to the creature and dances with it, upon which it turns into a prince. So in the end, you too will turn into a prince and live happily ever after...[7]

.

However, Juergen May argues that the program is more plausibly based on Homer: Odysseus lands on the island of Scheria and subsequently meets the princess Nausicaa.[8]

The work is written in three movements, although the second movement acts as little more than a brief transition between the outer movements. The dance like third movement is very much in the spirit of his oboe concerto. David Hurwitz writes that "Works such as this are unique and have no true antecedents in the orchestral literature...That Strauss wrote it at all is something miraculous"[9] May relates the piece to a comment Strauss had made in his 1904 update on Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, where he comments on a bassoon passage: "One can't help hearing the voice of an old man humming the melodies dearest to him when he was a youth".[10]

Instrumentation

The scoring of the concerto is distinctive. In addition to the standard strings and harp, Strauss divides the string sections into "Soli" (the lead player for each of the five sections) and "tutti" (the body of players) in the manner of the baroque concerto grosso. The opening bars feature the five solo players augmented by a second viola, making a septet reminiscent of the sextet which opens his opera Capriccio (opera).

Sources

- Del Mar, Norman (1986). Richard Strauss: A Critical Commentary on his Life and Works (2nd ed.) London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-25098-1.

- Hurwitz, David (2014). Richard Strauss: An Owners manual. Milwaukee: Amadeus Press, ISBN 978-1-57467-442-2.

- May, Juergen (2010). "Last works". In The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss, edited by Charles Youmans, 195–212. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-72815-7.

- Trenner, Franz. Richard Strauss Chronik, Verlag Dr Richard Strauss Gmbh, Wien, 2003. ISBN 3-901974-01-6.

- Warfield, Scott (2003). "From "Too Many Works" to "Writ Exercises": The Abstract Instrumental Compsitions of Richard Strauss", Chapter 6 in Mark-Daniel Schmid (editor) The Richard Strauss Companion, Praeger, Westport Conneticut, London. ISBN 0-313-27901-2.

!

References

- ^ Dixon, H. Friedenstag: a work extolling the union of peoples, Richard Strauss Society Newsletter 63 (2017), pages 5-8, London.

- ^ Rollo Myers, page 160.

- ^ Potter, page 420-22.

- ^ Howell, Anna The influence of politics on German cultural life during the third Reich, with particular reference to opera , Masters thesis, Durham University UK, 1983.

- ^ Potter, page 412.

- ^ Trenner pages 641, 647.

- ^ Del Mar, page 450

- ^ May, page 189.

- ^ Hurwitz, page 28.

- ^ May, pages 189-90.

Performance History

On 4 April 1948, the world premier was broadcast on Radio Lugano, with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana conducted by Otmar Nussio. Strauss was not present, but it is mentioned in his notebook indicating that he might have listened to the broadcast. The British premier was given at Manchester by the Halle Orchestra on 4 May 1949 with John Barbirolli conducting and the clarinet played by Pat Ryan and Bassoon by Charles Cracknell.[1]

Horn Concerto No. 2 (Strauss)

| Duett-concertino (F-Dur) fur Klarinette nd Fagott mit Streichorchstra und Harfe | |

|---|---|

| by Richard Strauss | |

| File:Gemalte Musik Till-Eulenspiegel-Richard-Strauss Ferry Ahrle 20130305.jpg Dennis Brain's Horn. | |

| Key | E Flat |

| Catalogue | TrV 293. |

| Composed | Completed 28 November 1942 |

| Dedication | To the memory of my father. |

| Scoring | Chamber orchestra. |

Richard Strauss composed his second horn concerto in E Flat (TrV 283) whilst living in Viennna in 1942. The work was premiered in 1943 at the Salzburg festival and recorded in 1944, both with solo horn Gottfried von Freiburg. The score was published by Boosey and Hawkes of London in 1950. It was taken up and popularised by the British horn player Dennis Brain. It has since become the most performed and recorded horn concerto of the 20th century.

Composition history

The premier of Strauss's opera Capriccio was on 28th October 1942. Strauss wrote "My life's work has been concluded with Cappriccio. Whatever notes I scribble down now have no bearing on musical history". [2]A couple of days later he drove to Vienna where he was to stay for over 6 months.[3] The horn concerto seems to have been written very quickly: his note book indicates that the draft was finished on the 11th November, and the final score two weeks later on the 28th (he added a note at the end "In the beautiful house at Vienna"). The autograph score indicates that it is dedicated "To the memory of my father", although this did not make it into the published version. The speed of composition may reflect it had been on his mind for sometime, as the principle horn player at Munich, Professor Josef Suttner, had asked him years before to write a second concerto. [4] Strauss also mentioned the second concerto in a program list written in 1941.[5][6]

Since he had finished the Alpine Symphony in 1915 until 1942, Strauss had devoted himself almost completely to operatic works, with no substantial orchestral works. The few works from this period include the ballet Schlagobers (1922), the two Couperin Suites (the 1923 Dance suite and the 1941 Divertimento) and Japanese Festival Music (1940). The Second Horn Concerto was the first in a series of late works often referred to as his Indian summer, which include Metamorphosen, his oboe concerto, ending with his most famous and popular work Four Last Songs written just before his death in 1949. He gave no opus number to any of these late works and none were published during his lifetime.

The Strauss family were not in a good place in late 1942. His wife Pauline had developed problems with her sight, whilst Richard developed serious influenza.[7] The safety of his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice and grandchildren remained precarious: part of the reason for staying in Vienna was the protection provided by the Nazi governor of Vienna, Baldur von Schirach, who was a great admirer of Strauss and his music. The mass deportations of Jews started in 1941. In the summer of 1942 Strauss had become involved in the unsuccessful attempts of his son Franz and Alice to help her relatives emigrate to Switzerland. Strauss himself visited Theresienstadt concentration camp where he greeted the SS guards with the words "I am the composer Richard Strauss" and was duly sent away without being able to see Alice's relatives who were incarcerated there (26 of Alice's Jewish relatives were to die before the end of the war).[8] Norman Del Mar wrote in 1972: "It is indeed hard to believe that this is the work of a depressed old man living in fear of disgrace from the authorities of a war-beleaguered country, so light and carefree a style did he capture"[9] Clearly, composing provided an escape from the uncertainty and horrors unfolding around him. It also reflected his aesthetic that art and Culture were the highest human achievement that transcended history. In 1900 he had set Uhland's song Des Dichters Abendgang (The poets evening stroll), which expressed this view that "When the dark clouds roll down..You carry within yourself the blessing of song. The light, that you saw there, Gently shines upon you on the dark paths."

Performance History

[[

The premier was given at the Salzburg Festival on 11 August 1943 with the horn player Gottfried von Freiberg (1908-1962), Karl Böhm conducting the Vienna Philharmonic.[10] The same combination recorded it soon after. Richard Strauss himself was not present at the premier, but had left the festival on the 9th August after conducting some all Mozart concerts. He had, however, worked with Böhm and Gottfried during his stay: the signed autograph manuscript used for the premier is dated August 8th. The concerto was played a second time on 26 May 1944, with the horn played by Max Zimolong and Karl Ellmendorff conducting the Dresden Staatskapelle.[11] British Horn player Dennis Brain performed it with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1948, later recording it with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch. The US premier was given on 8 October 1948 with soloist Anthony Miranda and the Little Orchestra of New York conducted by Thomas Sherman, and a year later at the Tanglewood with James Stagliano on horn and the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Eleazor de Carvalho. The concerto went on to become the most performed of 20th Century horn concertos (it was performed twice in the finals of the BBC young musician competition, in 1988 by the winner David Pyatt and in 2016 by runner up Ben Goldscheider).

The Concerto

The concerto is written in a conservative style that looks back to the musical world of his teenage years as represented by his First Horn concerto completed in 1883. Strauss follows the classical concerto structure of three movements with a rondo finale, with the three movements in E flat, A flat, E Flat. Juergen May writes:

"Still, there are "Straussian" melodic shapes, harmonic successions, and rhythmic characteristics that reveal the identity of their creator. The composer looks back to a past aesthetic from the perspective of someone who has lived through the paradigm changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In that respect, onde might call the work postmodern"[12]

Norman Del Mar wrote that "...the piece had turned into a singular success from first to last. It is the freedom and originality of form, especially in the opening allegro which reveals the experienced master as compared to the first concerto". Whilst the outer movements are virtuosic, the middle movement is a "beautifully proportioned miniature and particularly well conceived as a relaxation for the soloist between the exacting outer movements"[13]

Sources

- May, Juergen (2010). "Last works". In The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss, edited by Charles Youmans, 195–212. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-72815-7.

- Greene, Gary (1978): The two horn concertos of Richard Strauss. PhD Thesis, Butler University.

- Hurwitz, David (2014). Richard Strauss: An Owners manual. Milwaukee: Amadeus Press, ISBN 978-1-57467-442-2.

- Kater, Michael (2000).Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits, Oxford University Press. ISBN: 978-0195152869.

- Pizka, Hans (2000):Richard Strauss Horn concertos: some thoughts and facts

- Pizka, Hans (2002): Gottfried von Freiburg

- Richard Strauss, Recollections and Reflections, Willy Schuh (editor), Boosey and Hawkes, English Translation E.J.Jawrence, London, 1953. German original, 1949, Atlantis-Verlag, Zurich.

- Trenner, Franz. Richard Strauss Chronik, Verlag Dr Richard Strauss Gmbh, Wien, 2003. ISBN 3-901974-01-6.

- Warfield, Scott (2003). "From "Too Many Works" to "Writ Exercises": The Abstract Instrumental Compsitions of Richard Strauss", Chapter 6 in Mark-Daniel Schmid (editor) The Richard Strauss Companion, Praeger, Westport Conneticut, London. ISBN: 0-313-27901-2.

References

- ^ Kennedy, Nigel. The Halle 1858-1983: History of the orchestra. Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0719009211. Page 62.

- ^ May, page 179.

- ^ Trenner, page 617.

- ^ Prof. Pizka (2000)

- ^ Strauss, page 110.

- ^ Greene, page 32.

- ^ Del Mar, page 412.

- ^ Kater, Page255.

- ^ Del Mar, page 407.

- ^ Trenner, page 622.

- ^ Trenner, page 625.

- ^ May, page 181.

- ^ Del Mar, page 407-8.

Composition history

Stefan Zweig came up with the idea of the opera, which he outlined in a letter to Strauss following up a meeting between the two at the Salzburg festival in 1934. The basic plot remained the same except for a few minor changes. Both Zweig and Strauss were united in their common opposition to the growing militarism and anti-Semitism of the Nazis. After the debacle of Die Schweigsame Frau in 1935, Strauss could not work openly with the non-Aryan jew Zweig. However, they remained in contact about the work, even though much of the detail of the libretto was dealt with by Zweig's friend Gregor. The libretto amd draft of the opera were completed quickly, by 24 January 1936 and the orchestration six months later on 16 June. [1].

A Pacifist Attempt at Political Resistance

- "I fear that this work in which I put the best of myself will not be performed much longer. Will the cataclysm which we all fear soon break out?"

- Richard Strauss, in a letter to friend [2]

Pamela Potter argues that Zweig and Strauss constructed an opera whose surface aesthetic was acceptable to the Nazis, but had within it a clear pacifist and humanist message. It was an opera dealing with German history (the end of the thirty years war in 1648), with a central character of the commandant who appealed to the Nazi ideal of the loyal and dedicated soldier. “The message of peace thus shone through the masquerade of a National Socialist work”.[3] Strauss himself described it as “a work extolling the union of peoples”. [4]

The German audience of the opera would mostly have lived through the First World War and its aftermath of poverty, hunger and chaos. Some would have fought in the war. Most of them would have had sons, fathers, husbands, relatives and friends who were killed, maimed or suffered from “shell shock”. The humanist perspective is put into the mouths of the Mayor and townspeople who come to beg the commander to surrender. The townspeople express the hopelessness and desolation of war:

- Tell him what war is,

- The murderer of my children!

- And my children are dead,

- And the old folk whimper for food.

- In the wreck of our houses

- We must go hunting Foul rats to feed us.

The lord Mayor makes the pacifist argument that would have been familiar to readers of Remarque's 1929 novel All Quiet on the Western Front:

- Whom do you hope to defeat?

- I’ve seen the enemy, they’re men like

- they’re suffering out there in their

- trenches, just as we are. When they are

- they groan like us – and when they

- pray, they pray like us to God.

Zweig’s skill as a librettist is shown by his having the soldiers describe the approaching “rabble” of townspeople using the Nazi terminology used to denigrate Jews [5]:

- There’s a few grey rats swarming.

- Two thousand, three thousand, storming the gate!

- From the town!

- The enemy? Trouble.

- The enemy within. Arm yourselves!

- Who wastes powder on rats?

It was standard terminology in Nazi Germany to use the terms “rats” and “enemy within” to refer to Jews. Zweig at once calls on the audience to empathise with the historical plight of the townspeople in the light of their own recent experience and the plight of Jewry in contemporary Germany.

Potter argues that the symbolism of peace runs throughout the opera.

“Its symbols of peace are not very subtle: the belabored significance of the sun, the bells, and the character of Maria, who represents not only hope but also "woman" as the cultivator of peace in conflict with "man," the animal of war. The Piemonteser is an ambassador from the land of peace whose presence provokes the realization that those who have known only war can visualize peace only in their imaginations. Finally, the mayor, who pleads for humble surrender as the only road to survival, is perhaps Strauss himself.” [6]

The opera was performed about 100 times in Germany and Italy and its popularity stemmed from the fact that it allowed people to openly express the preference for peace over war in a politically acceptable and safe way. Performances were only halted after was under way. [7] Part of the reason the Nazis were willing to allow its performance was no doubt to reinforce the image their propaganda was seeking to promote that Germany did not want war. The premier was just a few weeks before the signing of the Munich agreement between Germany, Britain, France and Italy, hailed as “peace in our time” by the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlin.

The German critic Alexander Bersche hailed the work as “the first opera born from the ethos of the National Socialist Spirit,” and “inescapable reflection of ourselves is the most convincing proof of the artistic merit and human truth of the work, which shows courage and self-sacrifice, fear and denial, for what they are!”. Foreign reviewers were able to see more clearly the essentially pacifist nature of the work.

Musical legacy

q:Special:Search/Richard Strauss

Strauss was not employed at a musical academy and hence did not teach composition. Howevcer, the music of Strauss had a considerable influence on composers at the start of the 20th Centruy. Bela Bartók heard Also Sproach Zarathurstra in 1902, and later said that the work "contained the seeds for a new life".[8].

His own works began to reveal the harmonic, tonal and motivic influence of Strauss. This idiom guided him towards a new type of chromatic melody, later exemplified by such works as the first movement of his First String Quartet (1908-9)...Bartók's freer tonality and an almost continuous dissonant texture...may be primarily associated with the more daring harmonic fabric of Strauss' works, for example his opera Elektra (1906-8).[9]

A Straussian influence is also present in other works of that period such as Kossuth and Bluebeard's Castle. Karol Szymanowski was also greatly influenced by Strauss: "...three early works for orchestra - the Concert overture and his first and second symphony - bear the stamp of his infatuation with Strauss". [10] Other works of Szymanowski that were directly influenced by Strauss are his opera Hagith, which had as its prototype Salome. English composers were also influenced by Strauss, from Edward Elgar (for example In the South (Alassio))[11] to Benjamin Britten in his opera writing.

The musical style of Strauss played a major role in the development of film music in the middle of the 20th Century. His music addressed issues such as the description of character (Don Juan, Til Eulenspiegal, the Hero) and emotions that found their way into the lexicon of film music. Film music historian Timothy Schuerer wrote "The elements of post (late) romantic music that had greatest impact on scoring are its lush sound, expanded harmonic language, chromaticism, use of program music and use of Leitmotifs. Hollywood composers found the post-romantic idiom compatible with their efforts in scoring film" [12]. Max Steiner and Erich Korngold, came from the same muscial world as Strauss and were quite naturally drawn to write in his style. As film historian Roy Prendergast wrote "When confonted with the kind of dramtic problems films presented to them, Steiner, Korngold and Newman...looked to Wagner, Puccini, Verdi and Strauss for the answers to dramatic film scoring..."[13] Also, the opening to Also Sprach Zarthustra became one of the best known pieces of film music when Stanley Kubrik used it in his film 2001 a space odyssey.

"The elements of post (late) romantic music that had greatest impact on scoring are its lush sound, expanded harmonic language, chromaticism, use of program music and use of Leitmotifs. Hollywood composers found the post-romantic idiom compatible with their efforts in scoring film...Max Steiner and Erich Korngold, early pioneers and trend setters of film music came from Eastern Europe, home to composers Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss...young composers living in the shadow of these composers were quite naturally drawn to write in their style."[14] As film historian Roy Prendergast wrote "When confonted with the kind of dramtic problems films presented to them, Steiner, Korngold and Newman...looked to Wagner, Puccini, Verdi and Strauss for the answers to dramatic film scoring..."[15]

Nominal Rigidity in practice

There is now a considerable amount of evidence about how long price-spells last, and it suggests that there is a considerable degree of nominal price rigidity in the "complete sense" of prices remaining unchanged. A price-spell is a duration during which the nominal price of a particular item remains unchanged. For some items, such as gasoline or tomatoes, prices are observed to vary frequently resulting in many short price spells. For other items, such as the cost of a bottle of Champagne or the cost of a meal in a restaurant, the price might remian fixed for an extended period of time (many months or even years). One of the richest sources of inbformation about this is the price-quote data used to construct the Consumer price index, or CPI for short. The statistical agenices in many countries collect tens of thousands of price-quotes for specific items each month in order to construct the CPI index. In the early years of the 21st Century, there were several major studies of nominal price rigidity in the US and Europe using the CPI price quote microdata. The following table gives nominal rigidity as reflected in the frequency of prices changing on average per month in several countries. For example, in France and the UK, each month on average, 19% of prices change (81% are unchanged), which implies that an average price spell lasts about 5.3 months (the expected duration of a price spell is equal to the reciprocal of the freqeuncy of price change).

| Country (CPI data) | Frequency (per month) | Mean Price Spell duration (months) | Data Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| US[16], | 1998-2005 | ||

| UK [17] | 1996-2007. | ||

| Eurozone [18] | Various, covering 1989-2004 | ||

| Germany[19] | 1998-2004 | ||

| Italy[20] | 1996-2003 | ||

| France[21] | 1994-2003 |

The fact that price spells last on average for 3.7 months does not mean that prices are not sticky. That is because many price changes are temporary (for example sales) and prices revert to their usual or "reference price". [22] Removing sales and temporary price cuts raises the average length of price-spells considerably: in the US it more than doubled the mean spell duration to 11 months. [23] The reference price can remain unchanged for an average of 14.5 months in the US data.[22] Also, it is prices that we are interested in. If the price of tomatoes changes every month, the tomtoe price will generate 12 price spells in a year. Another price that is just as important (for example, tinned tomotoes) might only change once per year (one price spell of 12 months). Looking at these two goods prices alone, we observe that there are 13 price spells with an average duration of (12+13)/13 equals about 2 months. However, if we average across the two items (tomatoes and tinned tomatoes), we see that the average spell is 6.5 months (12+1)/2. The price spell duration is heavily influenced by prices generating short price spells. If we are looking at nominal rigidity in an econmy, we are more interested in the distribution of durations across prices rather then the distribution of price spells itself. [24] There is thus considerable evidence that prices are sticky in the "complete" sense, that the prices remain on average unchanged for a prolonged period of time (around 12 months). Partial nominal rigidity is less easy to measure, since it is difficult to distinguish whether a price that changes is changing less than it would if it were perfectly flexible.

Cello Sonata (Strauss)

"whether he use the piano arrangement of the orchestral version, or performaed an abridged version prepapred for him by the composer..it is no longer possible to say." Stephan Kohler, Preface.

Norman Del Mar wrote:

A Furher composition for the Cello, though this time with orchestral accompaniment, also belongs to this period, a most attractive Romanze which has unfortunately remained unpublished. It is a gentle 3/8 movement, similar in type to the slow movements of the violin and Horn concertos, both of which precede by date of composition.[26]

The piece was completed on 17 June 1883, and was perfromed a few times by Hans Wihan, who premiered it on 15 February 1884 at Baden-Baden and went on to perform it in Aachen, Freiburg, and elsewhere[27] It was deidcated to Anton Ritter von Knözinge. The piece somehow came to be forgotten, but was eventually published by Schott in 1987.[28] It was first performed in modern times by Cellist Jan Vogler, with the Orchestra of the Dresden Semperoper conducted by Günter Neuhold on 12 May 1986. The orchestra is double woodwind, two horns and strings.

| Le bourgeois gentilhomme | |

|---|---|

| orchestral suite by Richard Strauss | |

M. Jourdain, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, the title character in the play. | |

| Catalogue | Opus 60, TrV 228c. |

| Composed | 25 December 1917 |

| Scoring | Chamber orchestra. |

Richard Strauss composed his Cello Sonata in F Major Opus 6, TrV 115 in 1883 when he was 19 years old. It was dedicated to the Czech Cellist Hanuš Wihan, who gave the premier in 1883. It rapidly became a standard part of the cello repertoire and remains so.

Composition History

In 1882 Strauss was still based in Munich and attending University there. His sister Johanna was a good friend of Dora Wihan, a talented painist and wife of the cellist Hanuš Wihan (he was known by the first name Hans in Germany), who was in the Munich Court orchestra along with Richard's father Franz. "Through these relationships, Strauss came to know Wihan and his instrument's idiomatic possibilities".[29]. He composed and dedicated the sonata for "his dearest friend" (Seinem Lieben Freunde) . On the first manuscript, he added a verse by Austrian poet Franz Grillparzer:[30]

Music, the eloquent,

is at the same time silent.

Keeping quiet about the individual

She gives us the whole universe

In 1883 he revised the sonata into its current form, notably replacing the original finale with a completely new one. The sonata is in the traditional three movements:

- 1: Allegro con Brio

- 2: Andante ma non troppo.

- 3: Finale - Allegro vivo.

Performances

The premier was given on 6 December 1883 in Nuremburg, with Hans Wihan on cello and pianist Hildergard von Koenigs on the piano. On the 19th December of the same year, Strauss accompanied the principle cellist of the Dresden court orchestra Hermann Boekmann. Oscar Franz, a horn player in the orchestra, reported back to Franz Strauss:

Your son's wonderful sonata had a magnificent reception and is indeed a splendid work, full of original feeling, and everything flows so wholesomely from it. I take the greatest pleasure in your son's success.[31]

Willi Schuh notes that "Of all the works from this period of Strauss's creative life, the cello sonata is still the one that is heard most often",[32] and that "This sonata quickly became one of Strauss's most frequently performed works".[33]

The Dora Wihan-Weis affair

Richard Strauss became close to Dora, who was four years older than him. Sister Johanna Strauss wrote of Dora "She was like one of the family. Herr Wihan was insanely jealous over this pretty and already rather coquettish wife. I often witnessed scenes. When Richard was with us, we used to make music. She was very musical and an excellent piano player".[34] The marriage ended in divorce after a few years. Hans left to become a Professor at the Prague Conservatory and going on to found the celebrated Bohemian Quartet and later worked with Antonin Dvorak on his Cello Concerto in B minor. Dora and Richard developed a deep understanding and whole-hearted liking, and "there can be no doubt that they were in love fro some years".[35] Dora kept a photograph of Richard (inscribed To his beloved and only one, R) on her piano all her life. They wrote many letters to each other, which she ordered be destroyed on her death. Strauss also destroyed her letters to him: possibly because of his jealous wife Pauline de Ahna whom he married in 1894. There was a lot of gossip in Munich, and when Richard moved to Meiningen his father warned him of the need to preserve a spotless reputation: "Don't forget how people here talked about you and Dora W."[36] There is one surving letter from Richard to Dora, written in 1889:

"The fact is, that your letter, putting off the prospect of seeing you again for the forseeable future, has upset and distressed me deeply. God, what wooden expressions those are for what I really feel...Strauss the artist is doing very well! But may no happiness be complete?!"[37]

Recordings

The first recording of the sonata was made on December 1953, at the Beethoven-Saal, Hanover with Ludwig Hoelscher on the Cello accompanied by Hans Richter-Haaser. Another historic recroding was made on 28 September 1966, with Cellist Gregor Piatigorsky accompanied by Leonard Pennario, at the Webster Hall, New York issued on RCA Victor. There are many recordings of available, which include:

| CD title and release date (if known) | Cellist (pianist) | Label and Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Deutsche Grammophon: The Mono Era (2016) | Ludwig Hoelscher, (Hans Richter-Haaser) | DG 4795516 |

| Piatigorsky: Mendelsohn, Chopin, Strauss (2008) | Gregor Piatigorsky, (Leonard Pennario) | Testament SBT1419 |

| Strauss & Britten: Cello Sonatas (2006) | Yo-Yo Ma (Emanuel Ax) | Sony 82876888042 |

| Mischa Maisky - Morgen (2009) | Mischa Maisky, (Pavel Gililov) | DG 4777465 |

| Cello Sonatas: Strauss, Janacek, Pfitzner (2004) | Esther Nyffenegger,(Gerard Wyss) | Divox CDX252052 |

| Lorin Maazel Conducts R. Strauss (2014) | Steven Isserlis,Stephen Hough | RCA Classical Masters 88843015232 |

Composition history

Strauss completed his musical studies with his composition teacher, Friedrich Wilhelm Meyer, in February 1880 (he was a conductor and had been hired as a private teacher by Richard's father Franz Strauss since 1875). Strauss wrote the symphony whilst attending school, from the 12th March to 12 June 1880. He wrote to his mother "I'm getting on all right at school, the symphony is making jolly good progress, all four movements are are finished now. I've scored the Scherzo and almost all of the fist movement".[38] The four movements are:

- I. Andante Meastoso - Allegro Vivace.

- II. Andante

- III. Scherzo: Molto allegro, leggero - Trio.

- IV. Finale: Allegro Maestoso.

Scott Warfield wrote that "the symphony in D minor follows the same formal plans that Strauss had been studying for nearly five years. The outer movements are real sonata-allegro movements, now complete with true development sections. The slow movement draws on the same model and the Scherzo follows the standard binary form."[39] The first movement opens with a fifty bar slow introduction, laying out thematic material used later. As Werbeck notes, within this introduction, Strauss goes through a series of modulations in which one two bar theme is repeated in a sequence from D min, Bflat7, Eflat, B7, Emin, C, Fmin, Dflat, ending in F. This wondering tonality is in contrast to the otherwise conservative musical conception of the symphony, and perhaps prefigures the future Strauss.[40] The exposition starts with a shift to 3/4, and the transition uses thematic material both from the first theme and the introduction. "This opening movement aslo contains the first genuine development section in any symhonic work by Strauss. His technique for devlopment in this lengthy subsection (188 bars) consists primarily repeating the material...as it sequences through various harmonic levels. This section marks the first time that Strauss went beyond the safety of a codefied formal plan".[41] By the age of sixteen, Strauss was writing a symphony which "need not be excused as a "student" work"[42] As David Hurwicz notes, Strauss had a rare mastery of orchestration and in partiular writing for woodwind. "Colorful scoring that cativates the ear an never ftigues or bores the listener makes a work sound shorter than it really is, even one that has a rather stiff little fuguein the middle of it finale, s does the First Symphony."[43]

Performance history

The premier was given at the Odeon concert hall in Munich as part of the subscription concert series of the Academy of music on 30 March 1881. The conductor was Hermann Levi, who was the muscial director of the Munich Court opera from 1872-1896, and who was to premier Richard Wagner's Parsifal in 1882. The piece was later performed on 5 August 1893 by the Wilden Gung'l conducted by his father Franz Strauss.[44] Strauss' father Franz was much involved in the premier, copying out all of the orchestral parts by hand and playing in the orchestra.[45] Franz was so grateful to Levi for consucting the premier, he asked how he could thank him. Levi "promptly siezed the chance to ask the great horn-player to take part in the first performances of Parsifal at the Bayreuth festival in 1894". Despite his hostility to the works of Richard Wagner, Franz consented, taking Richard with him to the see Parsifal.[46]

Instrumentation

Although described as being for "large orchestra", the orchestral forces are modest for the time.

- Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons

- Four french horns, two trumpets, three trombones.

- Timpani

- Strings

Sources

- Schuh, Willi (1982). Richard Strauss: A Chronicle of the Early Years 1864-1898, (translated by Mary Wittal), Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24104-9.

- Trenner, Franz. Richard Strauss Chronik, Verlag Dr Richard Strauss Gmbh, Wien, 2003. ISBN 3-901974-01-6.

- Werbeck, Walter (1999). Introduction toRichard Strauss Edition, Orchestral works, Volume 19, Symphonies. Verlag Dr.Richard Strauss GmbH, Wien. Published by C.F.Peters, Wien, 1999.

- Warfield, Scott (2003), "From "Too Many Works" to "Writ Exercises": The Abstract Instrumental Compsitions of Richard Strauss", Chapter 6 in Mark-Daniel Schmid (editor) The Richard Strauss Companion, Praeger, Westport Conneticut, London. ISBN: 0-313-27901-2.

{{Portal bar|Classical

Standchen

!Ständchen!!Serenade[47]

Come out, come out, step lightly my love, Lest envious sleepers awaken, So still is the air, No leaf on the boughs above From its slumber is shaken. Then lightly, dear maiden, that none may catch, The tap of thy shoe, or the clink of the latch.

On top toe, on tip toe as moon spirits might Wondering over the the flowers Come softly down, through the radiant night To me in the rose hidden bowers The lillies are dreaming around the dim lake In odorous sleep, only love is awake.

Come nearer, Ah, see how the moonbeams fall, Through the wilow's drooping tresses The nightingales in the branches all shall dream of our caresses And the roses waking with morning light, Flush red, flush red, With the rapture born of the night.

Metamorphosen[48]

You will not weep. Softly, gently You will smile; and, as before a journey, I return your gaze and kiss. Our dear four walls! You made them, For you, I have opened them to the world. O happiness!

Then you will warmly take my hand And will leave your soul to me, Leave me to our children. You gave your life to me, I will hand it on again to them O happiness!

It will be very soon, as we both know. We have liberated each other from sorrow So I give you back to the world. Then, only in dreams will you appear to me And bless me and weep with me- O happiness!

When the earliest morning ray Through the valley finds its way, Hill and forest fair awaking, All who can their flight are taking.

And the lad who's free from care Shouts, with cap flung high in air, "Song its flight can aye be winging; Let me, then, be ever singing."

The first ray of morning sun flies through the quiet foggy dale, the awakening forest and hill rustle:

those who can fly, take flight!

And into the air the elated man throws his cap, exclaiming, "Song has wings as well, so let me sing merrily!"

Out you go, far into the world, dishearted and with dragging feet; what leaves you hopeless in the dark of night, morning shows it in a hopeful light.

Der Taillefer[49]

Compositon history

Taillefer is the hero of a romantic medieval tale set in the court of Duke William of Normandy (William the Conquerer) around the time of the invasion of England and the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Strauss used the version in a poem by Ludwig Uhland written in 1816. He had previously used several of Uhlands poems for songs, including Des Dichters Abendgang written in 1900. Professor Philip Wolfrum, music director,choir master at Heidelburg University commissioned the work, to be premiered in the new Town Hall in Heidelburg and and coincide with an the centenary of the university and the award of an honorary doctorate for Strauss.[50] In fact, Strauss had been working on early drafts of the piece in the summer of 1902, prior to the commission (Strauss first mentions it in is notebook on 20 April, whilst in Berlin). In May he spent a short holiday in England, including a visit to the beach at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, which further inspired him. [51][52] However, Strauss realized that a large scale choral work like this would be a perfect piece for the commission and event. Most of the work was done over the period July-November 1902. The honorary doctorate was confirmed in June (whilst Strauss was again visiting London)[53], and the premier arranged for 26th October 1903.

According to Norman Del Mar:

Uhland was always a most stirring writer and many of his poems have over the years taken on the popularity of folk songs. This particular ballad describes in heroic terms the Norman conquest and the courageous part played in it by Taillefer, Duke William’s favourite minstrel. Strauss thoroughly enjoyed making the most of the merry text. There are beautiful and exciting solos for baritone, tenor and soprano representing respectively Duke William, Taillefer and the Duke's sister. The chorus acts as narrator and commentator whilst the orchestra comes into its own with a graphic description of the battle of Hastings in a splendid interlude which even outdoes the battle scene in Ein Heldenleben. The whole score is carried through impetuously with a most infectious spirit, verging at times on the hilarious. [54]

Strauss described the piece as "written in the grandest music festival style", and the premier was noteworthy for innovative features to show off the new concert hall: the lights were lowered, the orchestra performed from a pit, and the large brass section was shifted to the back of the orchestra. Some were critical of the performance: critic and poet Otto Julius Bierbaum quipped that it was "a huge orchestral sauce".[55]

Lyrics

| Taillefer | Taillefer.[56] |

|---|---|

Normannenherzog Wilhelm sprach einmal: |

Once Norman Duke William spoke: |

Choir and Orchestra

In addition to the three soloists (Baritone,tenor and soprano) there is a mixed chorus split into eight parts, each of the four voices split into two. The orchestra consists of:

- Four flutes, two piccolos, four oboes, two English horns, six clarinets, two bass clarinets, Four bassoons, one double bassoon.

- Eight french horns, six trumpets, four trombones, two tubas

- Timpani and percussion.

- Strings: Twenty first and eighteen second violins, 1sixteen violas, fourteen cellos, twelve basses

However, whilst large, the orchestral resources were only slightly larger than Mahler was to use in his 8th Symphony of 1910 and less then Arnold Schoenberg in his Gurre-Lieder of 1911.

References

Notes

- ^ Trenner, page 567, 572.

- ^ Potter, page 420.

- ^ Potter, page 422.

- ^ Potter, page 422.

- ^ Patricia Josette Moss, Richard Strauss’s Friedenstag: A Political Statement of Peace in Nazi Germany, Dissertation, Master of Music, Louisiana State University, 2006, page 49

- ^ Potter, page 421.

- ^ Potter, page 422.

- ^ Elliott Antokoletz and Paolo Susanni, Béla Bartók: A Research and Information Guide, 2nd Revized edition edition (3 Dec. 1997), Routledge, London, ISBN 978-0815320883, Introduction page xxi.

- ^ Atonokoletz and Susanni, same page.

- ^ Paul Caldrin, "Orchestra music and orchestration", pages 166-169 in Paul Cadrin and Stephen Downes (editors), The Szymanowski Companion, Routledge, London, Revised edition (2015). ISBN 978-0754661511

- ^ Ian Parrott, Elgar (Master Musician), Everyman Ltd, London, First Edition (1971), page 60.

- ^ Timothy Scheurer, Music and Mythmaking in Film, Mcfarland, 2007 ISBN 978-0786431908. Page 41.

- ^ Roy Prendergast, Film Music: A neglected Art, W.W Norton & Company, 1992, ISBN 978 0393308747.

- ^ Timothy Scheurer, Music and Mythmaking in Film, Mcfarland, 2007 ISBN 978-0786431908. Page 41.

- ^ Roy Prendergast, Film Music: A neglected Art, W.W Norton & Company, 1992, ISBN 978 0393308747.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

KlenowKryvtsov2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bunnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Dhynewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hoffmann, J. and J.-R. Kurz-Kim (2006). 'Consumer Price Adjustment under the Microscope: Germany in a Period of Low Inflation', European Central Bank Working Paper Series Number 652.

- ^ Veronese, G., S. Fabiani, A. Gattulli and R. Sabbatini (2005). 'Consumer Price Behaviour in Italy: Evidence from Micro CPI Data', European Central Bank Working Paper Series Number 449.

- ^ Baudry, L; Le Bihan, H; Tarrieu, S (2007). "Integrating Sticky Prices and Sticky Information". Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 69 (2): 139–183.

- ^ a b Kehoe, Patrick; Midrigan, Virgiliu (2016). "Prices are sticky after all". Journal of monetary economics. 75 (September): 35–53. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2014.12.004.

- ^ Nakamura, Eli; Steinsson, Jon (2008). "Five facts about prices: a reevaluation of menu cost models". Quarterly journal of economics. 124: 1415–1464.

- ^ Baharad, Eyal; Eden, Benjamin (2004). "Price rigidity and price dispersion: evidence from micro data". Review of Economic Dynamics. 7 (3): 613–641.

- ^ Baharad, Eyal; Eden, Benjamin (2004). "Price rigidity and price dispersion: evidence from micro data". Review of Economic Dynamics. 7 (3): 613–641.

- ^ Del Mar, page17.

- ^ Schuh, page58.

- ^ Romanze for Cello and Orchestra in F, Mainz: Schott, CB 114, 1987. ISMN: 979-0-001-01750-3. Piano accompaniment published March 1988.

- ^ Warfield, page 207

- ^ Schuh, page 38-9.

- ^ Schuh, page 65.

- ^ Schuh, page 65

- ^ Schuh, page 58.

- ^ Wilhelm, page 29.

- ^ Wilhelm, page 29.

- ^ Wilhelm, page 30.

- ^ Wilhelm, page 30.

- ^ Schuh, page 48.

- ^ Warfield, page 201.

- ^ Werbeck, page XII.

- ^ Warfield, page 201-2.

- ^ Warfield, page 203.

- ^ Hurwicz, page 19-20.

- ^ Trenner, page 104.

- ^ Schuh, page 51.

- ^ Schuh, page 52-3

- ^ Sechs Lieder von A.F von Schack, Komponiert von Richard Strauss, Opus 7. No.2 Standchen. D Rather in Leipzig. 1912. English transaltion by Paul England.

- ^ Mrs A.L.W.Wister, (1914), in German Classics of the Nineteenth and twentieth Centuries: Masterpieces of German Literature translated intyo English, Volume 5, Edited by Kuno Francke, Patrons edition, The German Publicatins Society, 1914. page 118.

- ^ A.I. DU P. COLEMAN, (1914), in German Classics of the Nineteenth and twentieth Centuries: Masterpieces of German Literature translated intyo English, Volume 5, Edited by Kuno Francke, Patrons edition, The German Publicatins Society, 1914. page 100-101.

- ^ Del Mar, page 363-366.

- ^ Del Mar, page 363

- ^ Trenner, page 223-4

- ^ Trenner, page 240. Strauss was in London and Sandown for the whole month of June.

- ^ Del Mar, page 271.

- ^ Lodato, page 388.

- ^ Jefferson, page 26.

Sources

- Del Mar, Norman, Richard Strauss. A Critical Commentary on his Life and Works, Volume 2, London: Faber and Faber (2009)[1969] (second edition), ISBN 978-0-571-25097-4.

- Lodata, Suzanne, The Challenge of the Choral Works, chapter 11 in Mark-Daniel Schmid, Richard Strauss Companion, Praeger Publishers, Westfield CT, (2003), ISBN 0-313-27901-2.

- Trenner, Franz (2003) Richard Strauss Chronik, Verlag Dr Richard Strauss Gmbh, Wien, ISBN 3-901974-01-6.

Category:Songs by Richard Strauss

Category:1886 songs

Honors[1]

- 1903 (October 26th), Honorary Doctorate, Heidelberg University.

- 1907, Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur, 3rd Class, Paris, France.

- 1914 (June), Honorary Doctorate, Oxford University. Honorary citizen of Munich.

- 1924, Honorary Doctorate,, University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna. Freedom of the cities of Vienna and Salzburg.

- 1932, New York College of Music Medal.

- 1936, (November 5th) the Royal Philharmonic Society's Gold Medal.

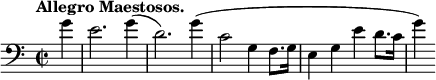

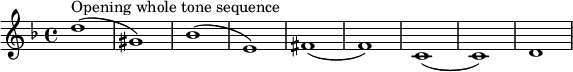

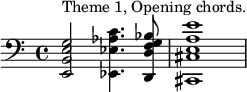

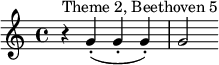

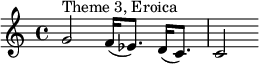

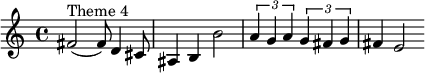

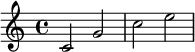

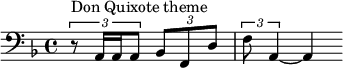

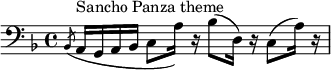

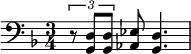

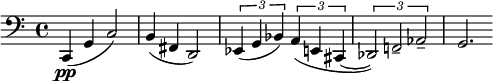

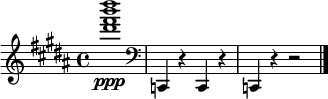

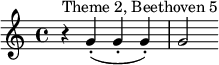

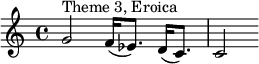

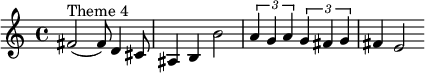

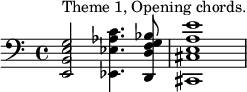

music notation

The themes are written here at the pitch they first occur:

![\relative c' {\clef "bass"

b2^"Theme 5" a4. b8 a2 g4. a8 g4 fis~ fis8 [g a b]

}](/upwiki/score/4/n/4njhg4qq89w3fp4zugawrbt8g5gp2nz/4njhg4qq.png)

examples

![\relative c' {\clef "bass"

b2^"Theme 5" a4. b8 a2 g4. a8 g4 fis~ fis8 [g a b]

}](/upwiki/score/4/n/4njhg4qq89w3fp4zugawrbt8g5gp2nz/4njhg4qq.png)

Horn Concerto 2

Weib und welt had a major impact on cotnemporary poets. Rilke wrote to Dehmel: "since I have come to know W&W, my admiration for you has grown enourmously. A bok of poetry like this comes along only once in a cnetury". ref: The Early works of Arnold Schoenberg 1893-1908, Walter Frisch page 81. same page open letter 23 June 1897. Cpurt case June 1897. Schonbergs song Erwartung and verklarte nacht is based on Dehmel, just a few years after Strauss.

lccn-n94098471

Writing about Die Frau Ohne Schatten in 1948, strauss said, despite the difficulties of staging it, "It has succedded nevertheless and has made a deep impression..., and music lovers in particular consider it to be my most important work".[2]

"Strauss was shattered by the effects of World War 2. The physical landmarks of his personal and musical life had been, to a large extent, destroyed and the German culture to which he had devoted his life lay in ruins as well. It is not surprising that he retreated into the musical world of hia youth, into memories of his farther and his early ideals" (page 32).

Strauss had been planning his seconds Horn concerto for sometime: it is on a "work in progress listing" made in 1941 and it finally appeared in 1942, with premier performance on August 11th 1943 at Salzburg. The soloist was the principle Horn of the Vienna Philharmonic, Gottfried von Freiberg. There is some dispute as to whether the conductor was Karl Bohm or Strauss himself. However, "it is highly likely that Strauss was present at the rehearsals, as he evidently gave von Freiberg a series of performance nuances which the player later passed on to the American Hornist Philip Farkas" (page 34).

US Premiers. October 8th 1948 (Anthony Miranda with the Little Orchestra of New York conducted by Thomas Scherman) and in Tanglewood in August 7th 1949 (James Stagliano with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Eleazer de Carvalho)

Published by Boosey and Hawkes in Ocotber 1950, in both full score and piano reduction.

Richard Strauss: The Two Concertos for Horn and Orchestra, Gary A. Greene, Thesis, Butler University, January 1978.

Malven

Malven[3]

Orchestra

The orchestral arrangement calls for:

- One piccolo, Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B, two bassoons, one contrabassoon.

- Four french horns in F, two trumpets in D, three trombones.

- Timpani

- Strings

References

Notes

- ^ Wilhelm, Kurt (1989), pages 298-99.

- ^ Richard Strauss “Recollections and Reflections”, Willy Schuh (editor), Boosey and Hawkes, English Translation E.J.Jawrence, London, 1953. German original, 1949, Atlantis-Verlag, Zurich. page 167

- ^ John M. Kissler, 'Malven': Richard Strauss's 'Letzte Rose!', Tempo, New Series, No. 185 (Jun., 1993), pp. 18-25

Sources

- Norman Del Mar, Richard Strauss. A Critical Commentary on his Life and Works, Volume 3, London: Faber and Faber (2009)[1968] (second edition), ISBN 978-0-571-25098-1.

- Schuh, Willi. Richard Strauss: A Chronicle of the Early Years 1864-1898, (translated by Mary Wittal), Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-521-24101-9 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: checksum.

- Trenner, Franz. Richard Strauss Chronik, Verlag Dr Richard Strauss Gmbh, Wien, 2003. ISBN 3-901974-01-6

Category:Compositions by Richard Strauss [[:Category:1884 compositions] Category:Choral compositions

sturnnnlied translate

He whom you do not forsake, Spirit, not the rain, nor the storm shall breath shivers o're his heart. Spirit, he whom you do not forsake shall to the raincloud, shall to the hailstorm sing against, like the lark, you, lark, there.

That one you do not forsake, Spirit, you shall lift above the muddied path with wings of fire. He will walk as with feet of flowers over Deucalion's devouring flood, slaying Python, weightless, enormous, A Pythian Apollo.

That one you do not forsake, Spirit, you shall wollen wings spread beneath. When he sleeps on the high cliffs, you shall wrap him in the guarded pinions of midnight's thicket.

He whom you do not forsake, Spirit, you shall in snow flurries envelope warmly; To warmth the Muses come, to warmth come the Graces.

Float round me, Muses, Graces. This is water, this the Earth, and the son of water and the Earth, over which I walk, as though a God.

You are pure, like the heart of water, you are pure, like the pulp of Earth, you float round me, and I float over water, over Earth, as though a God

(38 lines of 116). de:Wandrers Sturmlied

Metamorphosen

Prior to metamorphosen, Strauss had been working on (but never completed) a piece for strings titled Memorial Waltz, which some have argued developed into metamorphosen. However, apart from the different time signature (metamorphosen is in 4/4), the only overlap is the descending phrase from the bar 3 of the Eroica (which he also appeared in the opening sextet of Capriccio in triplet form (e.g. violas rehearsal mark 5)). Otherwise the memorial waltz was based on different thematic material (for example, themes from the opera Feuersnot relating to fire.

May, Juergen (2010). "Last works". In The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss, edited by Charles Youmans, 195–212. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-72815-7.

Alma mahler

She outlived Gustav Mahler by 50 years, destroying all but one of her letters to him, and suppressing or falsifying many of his to her for fear of being judged too harshly by posterity.[1]

Recordings

There have been many recordings of this piece, including:

| CD title | Orchestra and conductor | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Richard Strauss: Orchestral Works | Berlin Philharmonic, Wilhelm Furtwängler | Archipel Records: ARPCD0176 |

| Strauss, R:Metamorphosen | Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan | Deutsche Gramaphon DG: 4748892 |

| Tchaikovsky and Strauss | Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Iona Brown | Chandos CHAN9708 |

| Schoenberg, Strauss & Webern: Orchestral Works | Kremlin Chamber Orchestra, Misha Rachlevsky | Claves: 509412 |

| R. Strauss: Complete Orchestral Works (remaster 2014) | Staatskapelle Dresden, Rudolf Kempe | Warner Classics – 4317802 |

| Strauss: Oboe Concerto & Metamorphosen | Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra , Neville Marriner | Capriccio C10231 |

Evaluation of Taylor contracts

Taylor contracts have not become the standard way of modelling nominal rigidity in new Keynesian DGSE models, which have favoured the Calvo model of nominal rigidity. The main reason for this is that Taylor models do not generate enough nominal rigidity to fit the data on the persistence of output shocks.[2] Calvo models appear to do this with more persistence that the comparable Taylor models.[3]

RKM

The opera uses an orchestra with the following instrumentation:

- 3 flutes (piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, D-clarinet, 2 clarinets in B-flat and A, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (contrabassoon).

- 4 French horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- timpani,

- Percussion (3-4 players) glockenspiel, xylophone, 4 large bells, small bells, side drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, tambourine, rattle, castanets.

- harp, celesta, Harpsichord

- Strings 14, 12, 8, 8, 6.

- 3 flutes (piccolo,alto flute), 2 oboes, English horn, D-clarinet, 2 clarinets in B-flat and A, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (contrabassoon)

- 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- timpani, 4 bells, various percussion.

- harp, celesta, Harpsichord

- Strings

One of the Institute's primary goals — that of extolling and promoting "good German music", specifically that of Beethoven, Wagner, Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Brahms, Bruckner and the like — was to legitimize the claimed world supremacy of Germany culturally. These composers and their music were re-interpreted ideologically to extol German virtues and cultural identity. However, more generally there was no clear and consistent notion of what music in general should be and there were a variety of views within the Nazi movement.

The most consistent policy was to ban performances of works by Jewish composers. This applied to popular composers from the past such as like Mendelssohn and Mahler as well as living composers whether they were avant garde like Schoenberg or late-romantics like Ernest Bloch. Music by non-Jewish foreign composers remained performed, although with the outbreak of war in 1939, composers from enemy countries were largely proscribed. Atonality was seen as degenerate and some composers were criticized on this ground and performances of such works banned, even when the composers were supporters of the regime like Anton Webern. However, even here there were onconsistencies: Paul von Klenau, a Danish student of Schoenberg’s, managed to have his twelve-tone operas premiered on major German stages in 1933, 1937, 1939, and 1940.[4]

Stravinsky is a case which shows how ambiguous Nazi attitudes were. He was keen to have his music performed in Germany and indeed appeared in person at the Baden-Baden festival on 4 April 1936 to perform his Concerto for Two Pianos. His Jeu de cartes was given its European premier on 13 October 1937 at the Dresden Staatsoper.[5] The Firebird Suite was frequently performed and even the The Rite of Spring was put on a few times. However, he did face problems early on when he was put on a list of Jewish composers and it was often rumoured that he was Jewish despite the fact that he had supplied genealogical information to the authorities to establish his non-Jewishness. Furthermore, there was also criticism of some of his music as reflected by his inclusion in the “Degenerate Music” exhibition in Düsseldorf in 1938 (A Soldier's Tale was identified as being Jazz influenced). Unlike Stravinsky, the Hungarian Béla Bartók was an outspoken antifascist. However, his music continued to be performed. For example, the German premier of Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta was given on 31 January 1938 and followed by many performances.[6] During the war, since Hungry was an ally of Germany, performances of Bartock's works continued despite his having emigrated to the US to escape fascism.

Jazz and swing music were seen as degenerate and proscribed. Jazz was labelled Negermusik ("Negro Music");[7] and swing music was associated with various Jewish bandleaders and composers such as Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. Also proscribed were Jewish Tin Pan Alley composers like Irving Berlin and George Gershwin. However, the effectiveness of such bans is questionable given the growing popularity Jazz in Germany: performances and dances were simply done more discretely or in private.

Friedenstag

The opera also includes the Elektra chord which forms the basis for the Elektra leitmotif.

]].

The Elektra chord is a "complexly dissonant signature-chord"[8] and motivic elaboration used by composer Richard Strauss to represent the title character of his opera Elektra that is a "bitonal synthesis of E major and C-sharp major" and may be regarded as a polychord related to conventional chords with added thirds,[9] in this case an eleventh chord.

In Elektra the chord, Elektra's "harmonic signature" is treated various ways betraying "both tonal and bitonal leanings...a dominant 4/2 over a nonharmonic bass. Like Elektra herself, this chord is both monomaniacal and polymorphic." It is associated as well with its seven note complement which may be arranged as a dominant thirteenth[8] while other characters are represented by other motives or chords, such as Klytämnestra's contrasting harmony. The Elektra chord's complement appears at important points and the two chords form a 10-note pitch collection, lacking D and A, which forms one of Elektra's "distinctive 'voices'"[10]

Friedenstag as covert protest

- Musical quarterly POTTER (P. M.), Strauss’s Friedenstag: A Pacifist Attempt at Political Resistance, Vol. 69 No. 3 (1983), pp. 408-424

- 7 - The politics of peace: Friedenstag and Daphne pp. 238-271, Rounding Wagner's Mountain

Richard Strauss and Modern German Opera, By Bryan Gilliam, Cambridge Studies in Opera.

- Title: A hero's work of peace: Richard Strauss's Friedenstag, Author(s):Prendergast, Ryan Michael, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Thesis.

Fueursnot

strauss

- Resources

Nominal Rigidity

Nominal rigidity, also known as price-stickiness (and/or wage-stickiness), describes a situation in which the nominal price is resistant to change. Complete nominal rigidity occurs when a price is fixed in nominal terms for a relevant period of time. For example, the price of a particular good might be fixed at $10 per unit for a year. Partial nominal rigidity rigidity occurs when a price may vary in nominal terms, but not as much as it would if perfectly flexible. For example, in a regulated market there might be limits to how much a price can change in a given year.

If we look at the whole economy, some prices might be very flexible and others rigid. This will lead to the aggregate price level (which we can think of as an average of the individual prices) becoming "sluggish" or "sticky" in the sense that it does not respond to macroeconomic shocks as much as it would if all prices were flexible. The same idea can apply to nominal wages. The presence of nominal rigidity is an important part of macroeconomic theory since it can explain why markets might not reach equilibrium in the short run or even possibly the long-run. In his The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, John Maynard Keynes argued that nominal wages display downward rigidity, in the sense that workers are reluctant to accept cuts in nominal wages. This can lead to involuntary unemployment as it takes time for wages to adjust to equilibrium, a situation he thought applied to the Great Depression that he sought to understand.

In macroeconomics is also nominal rigidity crucial in explaining how money can effect the real economy and the classical dichotomy breaks down. If nominal wages prices were perfectly flexible, they would always adjust so that there would be equilibrium in the economy. Thus, for example, monetary shocks would lead to changes in the level of nominal prices, leaving quantities - output, employment for example - unaffected (this is sometimes called the neutrality of money). For money to have real effects, some degree of nominal rigidity is required so that prices (and wages) do not respond immediately.

Empirical evidence for sticky prices.

Nominal wages may also be sticky. Market forces may reduce the real value of labour in an industry, but wages will tend to remain at previous levels in the short run. This can be due to institutional factors such as price regulations, legal contractual commitments (e.g. office leases and employment contracts), labour unions, human stubbornness, human needs, or self-interest. Stickiness may apply in one direction. For example, a variable that is "sticky downward" will be reluctant to drop even if conditions dictate that it should. However, in the long run it will drop to the equilibrium level. Economists tend to cite four possible causes of price stickiness: menu costs, money illusion, imperfect information with regard to price changes, and fairness concerns.[citation needed] Robert Hall cites incentive and cost barriers on the part of firms to help explain stickiness in wages.

The first formal model of imperfect competition was developed by Antoine Augustin Cournot[11] (1801–1877). This model was a century ahead of its time and introduced the concept of the Nash equilibrium.

In Economics, Huw Dixon argues that it may not be necessary to analyze in detail the process of reasoning underlying bounded rationality.[12] If we believe that agents will choose an action that gets them "close" to the optimum, then we can use the notion of epsilon-optimization, that means you choose your actions so that the payoff is within epsilon of the optimum. If we define the optimum (best possible) payoff as , then the set of epsilon-optimizing options S(ε) can be defined as all those options s such that:

.

The notion of strict rationality is then a special case (ε=0). The advantage of this approach is that it avoids having to specify in detail the process of reasoning, but rather simply assumes that whatever the process is, it is good enough to get near to the optimum.

Edgeworth cycle

Nash equilibrium

- for main pages see Nash equilibrium and Cournot model

the Nash equilibrium is widely used in economics as the main alternative to competitive equilibrium. The Nash equilibrium is used whenever there is a strategic element to the behvior of agents and the "price taking" assumption of competitive equilibrium is inappropriate. The fist use of the Nash equilibrium was in the Cournot duopoly as developed by Antoine Augustin Cournot in his 1838 book.[13] Both firms produce a homogenous product: given the total amount supplied by the two firms, the (single) industry price is determined using the demand curve. This determines the revenues of each firm (the industry price times the quantity supplied by the firm). The profit of each firm is then this revenue minus the cost of producing the output. Clearly, there is a strategic interdependence between the two firms. If one firm varies its output, this will in turn affect the market price and so the revenue and profits of the other firm. We can define the payoff function which gives the profit of each firm as a function of the two outputs chosen by the firms. Cournot assumed that each firm chooses its own output to maximize its profits given the output of the other firm. The Nash equilibrium occurs when both firms are producing the outputs which maximize their own profit given the output of the other firm.

In terms of the equilibrium properties, we can see that P2 is satisfied: in an Nash equilibrium, neither firm has an incentive to deviate from the Nash equilibrium given the output of the other firm. P1 is satisfied since the payoff function ensures that the market price is consistent with the outputs supplied and that each firms profits equal revenue minus cost at this output.

Is the equilibrium stable as required by P3? Cournot himself argued that it was stable using the stability concept implied by best response dynamics. The reaction function for each firm gives the output which maximizes profits (best response) in terms of output for a firm in terms of a given output of the other firm. In the standard Cournot model this is downward sloping: if the other firm produces a higher output, your best response involves producing less. Best response dynamics involves firms starting from some arbitrary position and then adjusting output to their best-response to the previous output of the other firm. So long as the reaction functions have a slope of less than -1, this will converge to the Nash equilibrium. However, this stability story is open to much criticism. As Dixon argues: "The crucial weakness is that, at each step, the firms behave myopically: they choose their output to maximize their current profits given the output of the other firm, but ignore the fact that the process specifies that the other firm will adjust its output...".[14] There are other concepts of stability that have been put forward for the Nash equilibrium,evolutionary stability for example.

Bertrand

Bertrand competition is a model of competition used in economics, named after Joseph Louis François Bertrand (1822-1900). It describes interactions among firms (sellers) that set prices and their customers (buyers) that choose quantities at that price. The model was formulated in 1883 by Bertrand in a review [15] of Cournot's (1838) book in which Cournot had put forward the Cournot model. Cournot argued that when firms choose quantities, the equilibrium outcome involves firms pricing above marginal cost and hence the competitive price. In his review Bertrand argued that if firms chose pricers rather than quantities, then the competitive outcome would occur with price equal to marginal cost. The model was not formalized by Bertrand: however, the idea was developed into a mathematical model by Francis Ysidro Edgeworth in 1889.[16]

The model rests on very specific assumptions. There are at least two firms producing a homogeneous (undifferentiated) product and can not cooperate in any way. Firms compete by setting prices simultaneously and consumers want to buy everything from a firm with a lower price (since the product is homogeneous and there are no consumer search costs). If two firms charge the same price, consumers demand is split evenly between them. It is simplest to concentrate on the case of Duopoly where there are just two firms, although the results hold for any number of firms greater than 1.

A crucial assumption about the technology is that both firms have the same constant unit cost of production, so that marginal and average costs are the same and equal to the competitive price. This means that as long as the price it sets is above unit cost, the firm is willing to supply any amount that is demanded (it earns profit on each unit sold). If price is equal to unit cost, then it is indifferent to how much it sells, since it earns nothing. Obviously, the firm will never want to set a price below unit cost, but if it did it would not want to sell anything since it would lose money on each unit sold,

Equilibrium