Abbevillian

Abbevillian is a currently obsolescent name for a tool tradition that is increasingly coming to be called Oldowan (or Olduwan). The original artifacts were collected from road construction sites on the Somme river near Abbeville by a French customs officer, Boucher de Perthes. He published his findings in 1836.

Subsequently Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet (1821–1898), professor of prehistoric anthropology at the School of Anthropology in Paris, published (1882) "Le Prehistorique, antiquité de l'homme", in which he was the first to characterize periods by the name of a site. Many of his names are still in use. His first two were Chellean and Acheulean.

Chellean included artifacts discovered at the town of Chelles, a suburb of Paris. They are similar to those found at Abbeville. Later anthropologists substituted Abbevillian for Chellean, the latter which is no longer in use.

History

The label Abbevillian prevailed until the Leakey family discovered older (yet similar) artifacts at Olduvai Gorge (a.k.a. Oldupai Gorge), starting in 1959, and promoted the African origin of man.[1] Olduwan (or Oldowan) soon replaced Abbevillian in describing African and Asian paleoliths. The term Abbevillian is still used, but it is now restricted to Europe. The label, however, continues to lose popularity as a scientific designation.

Mortillet had portrayed his traditions as chronologically sequential. In the Abbevillian, early Palaeolithic hominins used cores; in the Acheulian, flakes. Olduwan tools, however, indicate that in the earliest Palaeolithic, the distinction between flake and core is less clear. Consequently, there also is a tendency to view Abbevillian as an early phase of Acheulian.

Provenience of the type

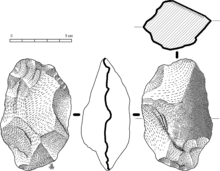

The Abbevillian type site is on the 150-foot terrace of the River Somme.[2] Tools found there are rough chipped bifacial handaxes made during the Elsterian Stage of the Pleistocene Ice Age, which covered central Europe between 478,000 and 424,000 years ago.

The Abbevillian is a phase of Olduwan that occurred in Europe near, but not at, the end of the Lower Palaeolithic (2.5 mya. – 250,000 years ago). Those who adopt the Abbevillian scheme refer to it as the middle Acheulian, about 600,000-500,000 years ago. Geologically it occurred in the Middle Pleistocene, younger than about 700,000 years ago.[2] It spanned the Günz-Mindel interglacial period between the Günz and the Mindel, but more recent finds of the East Anglian Palaeolithic push the date back into the Günz, closer to the 700,000 ya mark.[nb 1]

The Abbevillian culture bearers are not believed to have evolved in Europe, but to have entered it from further east. It was thus preceded by the earlier Olduwan of Homo erectus, and the Upper Acheulian, of which Clactonian and Tayacian are considered phases, supplanted it. The Acheulian there went on into the Levalloisian and Mousterian are associated with Neanderthal man.

Abbevillian tool users

Abbevillian tool users were the first Hominin inhabitants of Europe. They are generally considered to be the immediate ancestors of Neanderthal Man, whose classification, though not entirely undisputed, is most often given as Homo neanderthalensis; the other school believes that Neanderthal Man is a subspecies of modern man, as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Our own subspecies has for many generations been fixed at Homo sapiens sapiens.

Beyond these basic concessions, there is a dispute of a purely semantic nature. Three points of view are emergent:

- The first European men are late variants of Homo erectus; that is, not modern at all. And yet, those who hold and present this view make such concessions as:[3]

- "While the type is identified as Homo erectus, there are modifications that suggest it is filling a gap between Homo erectus and the Neanderthal."

- The first European men are a set of distinct species intermediary between Homo erectus and Neanderthal Man, such as Homo heidelbergensis (Heidelberg Man) and Homo antecessor (Atapuerca man).

- The first European men are early varieties of modern man, Homo sapiens:[4]

- "In Europe there are, as yet, no hominid[nb 2] fossils classified definitely as typical Homo erectus remains; all of the more compete skulls have been classified by most authorities as forms of archaic Homo sapiens."

Abbevillian sites in Europe

To avoid the question of what culture name should be used to describe European artifacts, some, such as Schick and Toth, refer to "non-handaxe" and "handaxe" sites.[5] Handaxes came into use at about the 500,000 ya mark.[nb 3] Non-handaxe sites are often the same sites as handaxe sites, the difference being one of time, or, if geographically different, have no discernible spatial pattern. The physical evidence is summarized in the table below Note that the dates assigned vary widely after 700,000 ya and, except where substantiated by scientific methods, should be viewed as tentative and on the speculative side.

| Site | Names | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Arago Cave near the village of Tautavel in the Languedoc-Roussillon region of France. | Homo erectus tautavelensis | A community of about 100 individuals discovered over the years in the ongoing excavations of the cave by a team of the Centre Européen de Recherches Préhistoriques de Tautavel under the direction of Henry de Lumley. Excavations began in 1964, the first mandible came to light in 1969, and the first "Tautavel Man" in 1971, though in fact many subsequent Tautavel men and women appeared. The date range is a fairly secure 690,000-300,000 years ago by many methods. The prevailing view is that the fossils are intermediary to the Neanderthals. Tools were found as well.[citation needed] |

| Barnfield Pit near Swanscombe in Kent, England | Swanscombe Man (female); Homo heidelbergensis |

Portions of a skull excavated from a gravel pit by Alvin T. Marston in 1935-36 along with handaxes and animal bones. Two more pieces and some charcoal were found in 1955 by John Wymer. Estimated date 250,000 ya.[citation needed] |

| Boxgrove, outside Chichester, Great Britain. | Homo heidelbergensis | Shin bone & two teeth found in 1994 and 1996 in a quarry, with butchered animal bones and handaxes, ca. 500,000 ya.[citation needed] |

| Mauer near Heidelberg, Germany | Homo Heidelbergensis; Mauer jaw |

Lower jaw & tooth discovered 1907 in a gravel pit.[6] Dated to 600,000-250,000 ya.[citation needed] |

| Petralona in Chalcidice, Greece. | Archanthropus europaeus petralonsiensis | Skull found in a cave with animal bones, stone tools and evidence of fire in 1960. Studied by Aris Poulianos, given various dates. ESR date range is 240,000-160,000, but all other fossils associated indicate a much older date circa 800,000.[7][8][9] |

| Sima de los huesos, "pit of bones", a chimney site in a cave, one of many fossil hominin sites in the hills of Atapuerca, Castile-Leon, Spain | Homo heidelbergensis | About 4,000 Hominin bones from which about 30 individuals have been reconstructed since the mid-1970s. Bones of carnivores are mixed in and a handaxe was found in 1998. Date is 500,000-350,000 ya.[citation needed] |

| Steinheim an der Murr, north of Stuttgart, Germany. | Homo heidelbergensis; Steinheim man |

Skull found in 1933[10] by Karl Sigrist, currently dated to about 250,000 ya.[citation needed] |

| Vértesszőlős, Vértesszőlős, near Budapest |

Homo erectus seu sapiens palaeohungaricus; Samu |

Occipital bone and a few teeth excavated 1964-65 in a quarry site that was in the open and used for butchery by László Vértes. Human fossils were with a hearth, dwelling, tools, footprints, plant and animal fossils.[citation needed] |

Notes

- ^ An important point to remember is that tool-makers advanced at different rates throughout the globe. For example, the style of tool-making that is called Abbevillian was practiced at a different time period in Africa than in Europe.

- ^ In accordance with the latest genetic classifications, Hominid, as used in this quote, refers to Hominin. Hominin, the sub-tribe, contains the Homo genus, whereas Hominid generally refers to the family Hominidae, but also has referred to Hominid, the sub-tribe, synonymous with Hominin.

- ^ Acheulean or later Acheulean, dated to 500,000-100,000 ya.

Footnotes

- ^ Daniel 1973, p. 105

- ^ a b Hoiberg 2010, p. 11

- ^ Rohrer 1983, p. 1

- ^ Schick & Toth 1993, p. 269

- ^ Schick & Toth 1993[page needed]

- ^ Cohen 1998, p. 1920

- ^ Kurtén 1983, p. 58

- ^ Poulianos 1983[page needed]

- ^ Cohen 1998a, p. 2418

- ^ Cohen 1998b, p. 3020

References

- Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998). "Mauer". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. Vol. 2: H to O. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5. LCCN 98071262.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998a). "Petralona Cave". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. Vol. 3: P to Z. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5. LCCN 98071262.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998b). "Steinheim an der Murr". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. Vol. 3: P to Z. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5. LCCN 98071262.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Daniel, Glyn (1973). Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. VIII: Jonathon Homer Lane - Pierre Joseph Macquer. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-10119-X. LCCN 69018090.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbevillian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-5933-9837-8. LCCN 2008934270.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kurtén, Björn (1983). "Faunal Sequence in Petralona Cave" (PDF). Anthropos. 10. Athens, Greece: 53–59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-12.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Poulianos, N. Aris (December 1983). "Faunal and Tool Distribution in the Layers of Petralona Cave". Journal of Human Evolution. 12 (8): 743–746. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(83)80129-8.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Rohrer, George W. (Winter 1983). "The First Settlers in France" (PDF). Old World Archaeologist. Old World Archaeological Study Unit: 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-12.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Schick, Kathy Diane; Toth, Nicholas (1993). Making Silent Stones Speak: Human Evolution and the Dawn of Technology. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-69371-9. LCCN 92035337.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

See also

Further reading

- Hennig, G. J.; Herr, W.; Weber, E.; Xirotiris, N. I. (August 6, 1981). "ESR-Dating of the Fossil Hominid Cranium from Petralona Cave, Greece". Nature. 292. UK: Nature Publishing Group: 533–536. doi:10.1038/292533a0.

- Wintle, A. G. (July 14, 1983). "Hominid Evolution: Dating Tautavel Man". Nature. 304. UK: Nature Publishing Group: 118–119. doi:10.1038/304118b0. ISSN 0028-0836.

External links

- The Abbevillian Culture, section in a pdf document. Search on Abbevillian.

- Early Palaeolithic. This site presents the view that Olduwan and Abbevillian are phases of the Acheulean.