Bishop Auckland

| Bishop Auckland | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within County Durham | |

| Population | 16,276 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NZ208294 |

| • London | 227 mi (365 km) SbE |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BISHOP AUCKLAND |

| Postcode district | DL14 |

| Dialling code | 01388 |

| Police | Durham |

| Fire | County Durham and Darlington |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

Bishop Auckland /ˈbɪʃəp ˈɔːklənd/ is a market town and civil parish in County Durham in north east England. It is located about 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Darlington, 12 miles (19 km) southwest of Durham and 5 miles (8 km) southeast of Crook at the confluence of the River Wear with its tributary the River Gaunless. According to the 2001 census, Bishop Auckland has a population of 24,392, recounted at 16,296 for the 2011 Census.[2] [dubious – discuss]

Much of the town's early history surrounds the bishops of Durham and the establishment of a hunting lodge, which later became the main residence of the Bishops of Durham.[3][4][5] This link with the Bishops of Durham is reflected in the first part of the town's name.[6]

During the Industrial Revolution, the town grew rapidly as coal mining took hold as an important industry.[7] The subsequent decline of the coal mining industry in the late twentieth century has been blamed for a fall in the town's fortunes in other sectors.[8] Today, the largest sector of employment in the town is manufacturing.[9]

Since 1 April 2009, the town's local government has come from the Durham County Council Unitary Authority. The unitary authority replaced the previous Wear Valley District Council and Durham County Council.[10] Bishop Auckland is located in the Bishop Auckland parliamentary constituency. The town has a town-twinning with the French town of Ivry-sur-Seine.[11]

Toponymy

The first part of the name, "Bishop", refers to the land being owned by and the town being the residence of the Bishop of Durham.[6][12][13] However, the derivation of "Auckland" is more complex.

The present form of the name almost certainly comes from Old Norse Aukland meaning 'additional land'.[12][13][14] This could refer to the area being extra land granted to the Bishop of Durham by King Canute in around 1020.[15] (Though another suggestion is that Auckland derives from "Oakland", referring to the presence of forests.)[6][16] (cf. also Languedoc; "Oc"-land to the south versus Languedoïl; "Oui or Aye"-land further north - these of course refer to France not 'Northumbria'/Scotland. 'Our height mes d'Auck'/'alright me duck'.)

However, the name is attested in an earlier, Cumbric form, Alclit,[12][15] (or Alcluith[17] or Alcleat).[6] This is similar to Alclut, an early, Cumbric name for Dumbarton which means "rock on the Clyde"[12] or "cliff on the Clyde".[13] It is believed[by whom?] that 'Clyde' may have been an earlier Celtic name for the river today known as the Gaunless, which flows close to the town. Thus before being Norseified as Aukland, Alclit meant 'rock of the [river] Clut'.[14]

Auckland is also used in the settlements of St Helen Auckland, West Auckland and St Andrew Auckland, an old name for South Church,[18][19] all of which are along the path of the Gaunless. The name Gaunless itself is of later Norse origin, meaning useless.[12][20] It is believed that this derives from the river's inability to power a mill, sustain fish or create fertile floodplains.[6][15]

Earliest history

The earliest known reference to Bishop Auckland itself is around 1000AD as land given to the Earl of Northumberland for defending the church against the Scots.[21] It is also mentioned in 1020 as a gift given to the Bishop of Durham by King Canute. However, a village almost certainly existed on the town's present site long before this, with there being evidence of church on the site of St Andrew's Church in South Church as early as the seventh century.[22] Furthermore, the Romans had a look-out post where Auckland Castle is sited today and a 10-acre (0.04 km²) fort at nearby Binchester. There is also evidence of possible Iron Age settlements around the town,[23][24] together with finds of Bronze Age,[25] Neolithic[26] and Mesolithic[27][28] artefacts.

The Bishops of Durham

Much of the town's history surrounds its links with the Bishops of Durham. In 1083, Bishop William de St-Calais expelled a number of canons from Durham. Some of these settled in the area and established a collegiate church.[22] Around 1183 Bishop Pudsey established a manor house in the town, with a great hall being completed in 1195 on the site occupied by St Peter's Chapel today.[3][21] Bishop Bek, who preferred the town as his main residence over Durham Castle due to its proximity to hunting grounds, later converted the manor house into a castle. The grounds of the castle were noted as being large enough to contain 16000 men ahead of the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346.[21]

Between 1283 and 1310, Bek was also responsible for ordering the replacement of the collegiate church established in 1183 with the Church of St Andrew that stands in South Church today,[22] together with accommodation for the canons; the building known today as the East Deanery.[29]

The collegiate church also appears to have supported a school. The collegiate church was re-organised under Bishop Langley in 1428 and at some point in the same century moved to the castle grounds. The college and its school were finally dissolved in the 15th century.[30] [31][32]

The school was not revived until the reign of King James I when in 1604 Anne Swifte petitioned the King to found a school and the Free Grammar School of King James, the direct antecedent of today's King James I school, was established. Although, the school's early location is unknown, in 1638 Bishop Morton granted the school space in an old chapel in the Market Place.[32][33]

Also in 1604, James's son, the future King Charles I made the first of three visits he would make to the town during his life. On this visit, his first to England, he was entertained by Bishop Matthew. James himself stayed in Auckland Castle between 17 and 19 April 1617.[34] Later, on 8 May, at Durham Castle King James is reputed to have rebuked Bishop William James so badly that the Bishop returned to Auckland Castle and died three days later.[35]

Charles's second visit to the town was on his way to Scotland on 31 May 1633, when he was entertained by Bishop Morton. His third visit on 4 February 1647 was in less lavish circumstances, as a prisoner. Morton had fled the town in 1640 and the castle was empty.[34][35] Consequently, the king had to stay in a public house off the Market Place owned by Christopher Dobson.[36]

After the dis-establishment of the Church of England, at the end of the first civil war, Auckland Castle was sold to Sir Arthur Hazelrig, who demolished much of the castle, including the chapel, and built a mansion.[37][38][39] After the restoration of the monarchy, the new Bishop of Durham, John Cosin, in turn demolished Hazelrig's mansion and rebuilt the castle converting the banqueting hall into the chapel that stands today.[37][40]

Industrial Revolution

By 1801, the town had a population of 1861.[5] At the end of the eighteenth century the town had no notable roads other than the Roman road, and little trade beyond weaving.[7][41] Although, coal mining had existed on a small-scale as early as 1183 when it is mentioned in the Boldon Book,[42] it was limited by the lack of an easy way to transport coal away from the area.[43] All this changed with the arrival of railways in the early nineteenth century, which allowed large scale coal mining.[44] The railways allowed coal to be mined, and then transported to the coast before being put onto ships to London and even abroad.[45]

Around the same time, the Bishop, Shute Barrington was a keen proponent of the use of education to improve the social and moral circumstances of the lower social classes. He used £70,000 received from lead mining royalties in Weardale to fund the establishment of a number of schools in the area. One of these schools was the Bishop Barrington School, one of the town's three comprehensive schools today.[46] The Bishop Barrington School opened on 26 May 1810, the Bishop's own birthday. The school even allowed girls to attend until the age of 11 years.[47] Barrington's support of education for the poor was not without controversy. Some suggested education of the poor would lead people to question their position in society, others even blamed it for the French Revolution.[48][49]

Barrington's successor, William van Mildert was involved in the creation of Durham University. Durham Castle was donated to the new university and Auckland Castle, usually the preferred residence by successive Bishops, became the Bishop of Durham's official residence in 1832.[4] However, the influence of the Prince Bishops of Durham was on the wane and there was pressure for reform. Van Mildert would be the last Prince Bishop. Shortly after his death, in 1836, the position was stripped of its ancient powers and wealth.[50][51]

By 1851 the population of the town had more than doubled to 5112,[5] with a great proportion of them working in ironworks and collieries.[7] By 1891, the population had doubled again.[52] In the second half of the nineteenth century there were typically around 60 collieries in the area open at any one time.[53] By the turn of the twentieth century 16,000 people were employed in the mining industry in the area.[54]

The town also became an important centre for rail, with large amounts of minerals such as coal, limestone and ironstone mined in the surrounding area passing through the town on the way to the coast.[55] In the neighbouring town of Shildon large numbers were employed in the railways, where a railway engine works was established.[56]

Industrial decline

By the early years of the twentieth century coal mining started to go into decline as coal reserves started to become exhausted. By the end of the 1920s unemployment had hit 27% and the population too had started to decline, as colliery employment had halved compared with ten years previously.[57][58] With the onset of the Great Depression unemployment rose to 60% in 1932 before easing back to 36% in 1937.[58] The Second World War offered a temporary reprieve for the coal industry, however, after the war the decline continued.[59] The last deep colliery in the area closed in 1968, although drift mines and the much more mechanised and less labour-intensive surface level opencast mining did continue.[60]

Equally, the railways that had also supported the area were also scaled back,[30] ultimately culminating in the closure of Shildon's Wagon works in 1984 with the loss of thousands of jobs.[61]

Governance

For a large part of the county's history, the powers held by the Bishop of Durham meant that the county virtually operated as an independent state from the rest of England. A steward of Bishop Antony Bek in the thirteenth century is quoted as saying England had two kings; the king and the Bishop of Durham.[62] The Bishops of Durham were not stripped of the last of their temporal powers until shortly after the death of Bishop William Van Mildert in 1836.[51]

At the end of the nineteenth century the Local Government Act 1894 created Bishop Auckland Urban District council. From 1894 to 1974, the town was governed by the Urban District council within the administrative county of Durham. The district was enlarged to include a number of surrounding settlements in 1937 when Auckland Rural District and Willington Urban District were abolished.[63] The Urban District was scrapped under the Local Government Act 1972 and replaced by a two tier district and county council system. Under the system Bishop Auckland was governed by Wear Valley District Council at the district level and Durham County Council at the county level.

A third tier was added at the May 2007 local elections when a new town council was established. After the elections, the council elected Barbara Laurie as the town's first mayor.[64]

Under proposals approved by the government on 25 July 2007, Durham County Council and Wear Valley District Council were replaced on 1 April 2009 by a single unitary authority serving the whole of County Durham.[10][65]

The town is a part of the Bishop Auckland parliamentary constituency, and is currently represented at Westminster by Helen Goodman MP (Labour). The town is in the North East England European Parliament constituency.[66]

The town is located in the South Area of the Durham Constabulary,[67] and served by the County Durham and Darlington Fire and Rescue Service and North East Ambulance Service.

Bishop Auckland is twinned with the French town of Ivry-sur-Seine, whilst the wider Wear Valley district is twinned with Bad Oeynhausen in Germany.[11]

Geography

Bishop Auckland is located at 54°39′36″N 1°40′48″W / 54.66000°N 1.68000°W (British national grid reference system: NZ208294) on the Durham coalfield at the confluence of the River Wear with its tributary the River Gaunless.[3] The town nestles in the rivers' valley about 100 metres (330 ft) above sea level. Besides this the town is all but is surrounded on all sides by hills ranging in height from around 150 metres (490 ft) above sea level to over 220 metres (720 ft) above sea level.

Bishop Auckland is located about 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Darlington and 12 miles (19 km) southwest of Durham. The town is served by Bishop Auckland railway station, which marks the point where the Tees Valley Line becomes the Weardale Railway. The town is not served directly by any motorways.

Notable wards include Cockton Hill, Woodhouse Close, and Henknowle. Additionally, once neighbouring villages such as South Church, Tindale Crescent, St Helen Auckland, and West Auckland now more or less merge seamlessly into the town.

Climate

| Bishop Auckland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The nearest Met Office weather station to Bishop Auckland is located 8 miles (13 km) north-east of Bishop Auckland in Durham. The following local figures were gathered at this weather station between 1971 and 2000.

Like the rest of the United Kingdom, Bishop Auckland has a temperate climate. At 643.3 millimetres (25.33 in)[68] the average annual rainfall is lower than the national average of 1,125 millimetres (44.3 in).[69] Equally there are only around 121.3 days[68] where more than 1 millimetre (0.039 in) of rain falls compared with a national average of 154.4 days.[69] The area sees on average 1374.6 hours of sunshine per year,[68] compared with a national average of 1125.0 hours.[69] There is frost on 52 days[68] compared with a national average of 55.6 days.[69] Average daily maximum and minimum temperatures are 12.5 °C (54.5 °F) and 5.2 °C (41.4 °F)[68] compared with a national averages of 12.1 °C (53.8 °F) and 5.1 °C (41.2 °F) respectively.[69]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Demography

| Bishop Auckland Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2001[9][75] | Bishop Auckland | County Durham | England and Wales |

| Total population | 24,392 | 493,484 | 52,041,916 |

| Foreign born | 1.5% | 2.0% | 8.9% |

| Buddhist | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.3% |

| Christian | 84.8% | 83.5% | 71.7% |

| Hindu | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.1% |

| Muslim | 0.2% | 0.2% | 3.0% |

| No religion | 7.3% | 9.3% | 14.8% |

| Over 65 years old | 17.2% | 16.7% | 15.46% |

| Unemployed | 5.0% | 4.8% | 4.3% |

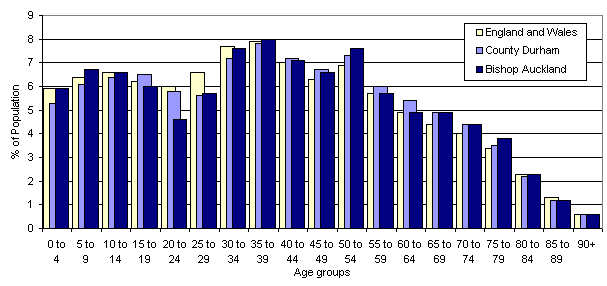

According to the 2001 census, Bishop Auckland has a population of 24,392, living in 10,336 dwellings. Of these dwellings, around 44% are terraced houses, 33% semi-detached houses, and 17% detached houses. As shown in the graph, the distribution of ages in Bishop Auckland was broadly in-line with that of County Durham and England and Wales, although there is a slightly smaller proportion of people between 20 and 24 years old.

Compared with the national average, the town's population performs poorly with regard to qualifications. At 31.9%, the proportion of the town's population with no qualifications is significantly higher than the national average of 23.2% and 29.1%. Similarly, only 13.8% have a degree level qualification (or higher) compared with the national average of 21.1%.

84.8% of the town's population identify themselves as Christian, compared with a national average of 71.7%. There are below averages numbers identifying themselves as belonging to other religion. The people of the town are also more likely to be religious than the national average with only 7.3% stating they had no religion compared with the national average of 14.8%.

At 1.5% of the population, the town has a below average population of foreign born individuals, compared with a national average of 8.9%.

Economy

At the end of the eighteenth century the town is noted as having little trade beyond weaving.[7][41] The first mention of coal mining in the area is in the Boldon Book of 1183,[42] but early coal mining was limited by the lack of an easy way to transport coal away from the area.[43] The arrival of the railways transformed the town as it allowed coal to be mined, and then transported to the coast before being put onto ships to London and even abroad.[45] At the start of the twentieth century 16,000 people were employed in the mining industry in the area.[54] However, by 1915 the coal industry in the town had started to decline as coal reserves started to become exhausted.[57] The last deep colliery in the area closed in 1968.[60]

Today, with the decline of the Durham coalfield, manufacturing has been left as the largest sector of employment in the town, accounting for 24.6% of the town's employment.[9]

The town also traditionally had a strong retail sector.[8] As one of the county's main population centres with good bus and rail connections, and thriving markets on Thursdays and Saturdays, shoppers were attracted from smaller settlements on the Durham coalfield for miles around. However, the decline in the coal mining industry, along with increased car ownership and competition from local shopping malls such as the MetroCentre in Gateshead, have caused a downturn in the fortunes of retailers,[76] with commentators lamenting the number of down market stores and charity shops in the town centre.[77] In response, numerous initiatives to regenerate the town centre have been proposed, including the launch of the Bishop Auckland Town Centre Forum,[78] and the 2006 regeneration master plan drawn up by Red Box Group, which was sponsored by Wear Valley District Council and the regional development agency One NorthEast.[79]

Notable employers in the town include Ebac, which is headquartered in the town and employs 350 people.[80]

Landmarks

The town has a number of Grade I listed buildings. The grounds of Auckland Castle alone contain seven such structures.[81] Additionally Escomb Saxon Church,[82] St Andrew's parish church,[83] St Helen's church,[84] St Helen Hall,[85] West Auckland Manor House,[86] the East Deanery[87] and the 14th century Bishop Skirlaw bridge are all Grade I listed.[88] Other notable buildings include the town hall, a Victorian railway viaduct and Binchester Roman fort.[89]

Auckland Castle

Auckland Castle (often known locally as The Bishop's palace), has been the official residence of the Bishop of Durham since 1832. However, its history goes back much earlier, being established as a hunting lodge for the Prince Bishops of Durham.[4] The castle is surrounded by 800 acres (3.2 km2) of parkland, which was originally used by the Bishops for hunting and is today open to the public.[90] The castle and its grounds contain seven Grade I listed structures.[81]

The castle's long dining room is home to 12 of the 13 17th century portraits of Jacob and his 12 sons painted by Francisco de Zurbarán, which were saved by Bishop Trevor in 1756.[91] Trevor was unable to secure the 13th, Benjamin, so commissioned Arthur Pond to produce a copy, which hangs alongside the 12 other originals.[92]

Auckland Castle also provides the setting for Lewis Carroll's story "A Legend of Scotland".

Binchester Roman Fort

The route of the Roman road Dere Street passes straight through the middle of the town on its way to the nearby Roman Fort at Binchester. Binchester Roman Fort, or Vinovia as it was known to the Romans, has one of the best preserved examples of a Roman military bath house hypocaust in the country.[93] Bishop Auckland's main shopping street, Newgate Street, together with Cockton Hill Road and Watling Road faithfully follow the route of Dere Street.[94] Note that Watling Road should not be confused with the Roman road Watling Street, which is in the South of England.

Town Hall

The Town Hall is a "Gothic style" Victorian Building overlooking the town's market place and is Grade II* listed.[95] After being abandoned and then condemned for demolition in the 1980s, the town hall was fully restored in the early 1990s. It now houses the town's main public library, a theatre, an art gallery, tourist information centre and a café-bar.[96]

The Town Hall has held three exhibitions for mining artist Tom Lamb. The first was held in 1999 for his 'Fading Memories' exhibition, then in 2004 for Lamb's 'The Footprints Of My Years' exhibition and in 2008 the last exhibition called 'My Mining Days' was held.

Newton Cap viaduct

The town also has a Grade II listed Victorian railway viaduct crossing the River Wear.[97] At 105 feet (32 m) high, the viaduct provides views of the surrounding countryside below as well as Auckland Castle, the Bishop's Park and the Town Hall on approaching the town from the Viaduct. It was originally built in 1857[97] to carry the Bishop Auckland to Durham City railway line across the River Wear and the Newton Cap Bank that leads down to the river. The railway closed in 1968 and the viaduct fell into a period of disuse and was at one point threatened with demolition.[98] However, in 1995, the viaduct was converted for vehicle use to take traffic on the A689 between Bishop Auckland and Crook, relieving the Grade I listed[88] fourteenth century single lane Bishop Skirlaw bridge which sits in the valley below it.[96][99]

Escomb Saxon church

The nearby village of Escomb is home to a complete Anglo-Saxon church. It is believed the church was built between the years 670 and 690.[100] Much of the stone used to construct the church came from the nearby Roman fort at Binchester, with some stones having Roman markings on them.[93][100] The church is a Grade I listed structure.[82]

St Andrew's Church

St Andrew's church located in the adjoining village of South Church is the largest church in County Durham[101][102] and a Grade I listed building. The church was built in the thirteenth century and acted as a collegiate church.[83][103]

Transport

The town has links with the birth of the railways, with the original 1825 route of the Stockton and Darlington Railway passing through West Auckland. Timothy Hackworth, a well-known locomotive builder, built steam locomotives in the neighbouring town of Shildon.[104]

Today, Bishop Auckland railway station still provides passenger services, and is located at the end of the Tees Valley Line. Since May 2010 it has been re-connected with the Weardale Railway, which provides passenger services up the valley to Stanhope. The town centre had a large railway goods yard until 1972.[96] Freight traffic ceased to use the line completely in 1993 when Blue Circle cement stopped using the line to transport cement from its works in Eastgate.[105]

The nearest airport to the town is Durham Tees Valley Airport at around 19 miles (31 km) drive South-East of Bishop Auckland. The nearest motorway junction is Junction 60 of the A1(M), which is around 8 miles (13 km) away.

The town has a bus station with a number of bus routes serving the town. Following the withdrawal of the Go-Ahead Group from the town on 8 April 2006, most of these services are provided by Arriva.[106] However, a number of smaller firms such as Weardale buses also serve the town.

Education

Legend

Legend

The town itself has three secondary schools—St John's Catholic School, The Bishop Barrington School and King James I Academy. The town also has a college, Bishop Auckland College serving the Further Education and Higher Education fields. Both Bishop Barrington and King James schools have long histories, being founded in 1810 by Bishop Barrington and in 1604 on the orders of King James I respectively.[16][124]

In the government's Level 2 CVA (Contextual Value Added) statistic, which measures how much a school improves students between the end of National Curriculum Key Stage 2 and the end of Key Stage 4, compared with how much other schools in the country improve students with similar circumstances, King James scored 1039.9 points, Barrington 1019.3 points and St John's scored a below average 997.4 points (with 1000 points being the target baseline).[117]

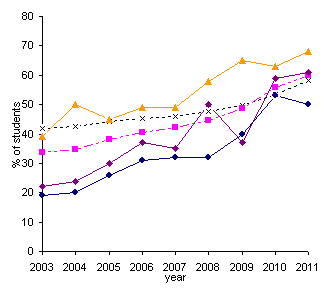

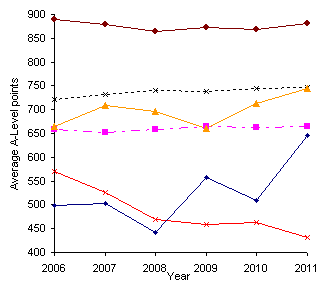

At A-Level in 2009, none of the towns sixth form centres average points scores reached the national average of 739.1 A-Level points per student or the LEA average of 664.1 points. Amongst sixth form centres in the town, St John's performed best with an average score of 661.5 points per student. In comparison, King James had an average A-Level score of 557 points and Bishop Auckland College with 459.3 points taking last position in the LEA in terms of A-Level point score, a position occupied by King James in the previous year.[111][113] The Bishop Barrington School no longer has its own sixth form, with the school being a feeder for Queen Elizabeth Sixth Form College in Darlington. The average A-Level points score at Queen Elizabeth is 871.8.[119] The needs of those with special educational needs are served by Evergreen Primary.

Schools in the town serving primary age education are detailed in the table below.

Public services

Healthcare

As is the case with the rest of the UK, the population of the town is served by the National Health Service (NHS). The town has its own NHS hospital, Bishop Auckland General Hospital. The current Bishop Auckland General Hospital has 286 beds, and since opening in 2002 has become a centre specialising in routine surgery.[125] Although Bishop Auckland General Hospital was built with an Accident and Emergency department, this was closed and replaced with an "Urgent Care Centre" in 2009, when the local NHS trust concentrated acute health care services at Durham and Darlington, and moved more routine surgery to Bishop Auckland General.[126][127]

The new hospital was a PFI project and was announced by the Labour government in the summer of 1997.[128] It replaced the old Bishop Auckland General Hospital which had been housed in the town's workhouse buildings[129] and temporary huts constructed during World War II.[130]

Other local hospitals include Darlington Memorial Hospital and University Hospital of North Durham, which has replaced Durham Dryburn and was announced on the same day as the new Bishop Auckland General. All three of these hospitals are run by County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, which provides secondary health care services in the area.[131] The local ambulance service is North East Ambulance Service.

Utilities

Bishop Auckland's water and sewerage is managed by Northumbrian Water. Water supply comes from Burnhope Reservoir via the Wear Valley water treatment works at Wearhead. The present treatment works replaced old works on the site of the present one and another one closer to the town at Tunstall Reservoir.[132] Contrary to popular belief the town does not receive water from Kielder Reservoir. Although water from Kielder can be pumped into the River Wear, via the Tyne–Tees tunnel, upstream at Frosterley, this water is not abstracted from the river until it reaches Chester-le-Street. Equally, although water can be pumped from the tunnel into Waskerley Reservoir, which in turn supplies Tunstall Reservoir, Tunstall water treatment works was closed in 2004, when the new Wear Valley works was brought into service.[133][134]

The electricity distribution network operator for the area is the CE Electric-owned NEDL (Northern Electric Distribution Limited). There are no power stations in the town.

Religion

The town has 3 Grade I listed churches; the Church of St Helen,[84] the Church of St Andrew,[83] and St Peter's chapel at Auckland Castle.[81] Another Grade I listed church, the Saxon church at Escomb is also close to the town. [82] Additionally, the town has 3 grade II listed churches; Bishop Auckland Methodist Church on Cockton Hill Road, [135] St Anne's church next to the town hall in the Market Place,[136] and St Peter's Church on Princes Street.[137]

The town is in the located within the Auckland Deanery and Archdeaconry of the Anglican Diocese of Durham.[138] The Diocese has its administrative offices at Auckland Castle in the town.[139] In the Roman Catholic faith the town is located in the St William Deanery of the Cleveland and South Durham Episcopal Area of the Hexham and Newcastle Diocese.[140]

Other denominations are also represented in the town. For example, the Baptist Church is next door to the hospital. Bishop Auckland Baptist Church is part of the family of the Baptist Union of Great Britain.[141] and is part of the Northern Association of Baptist churches [142]

Sports

Bishop Auckland is famous for its amateur football team, Bishop Auckland F.C., which won the FA Amateur Cup a record 10 times in the Trophy's 80-year history, having appeared in the Final on 18 occasions.[143] Bishop Auckland Football Club also helped out Manchester United after the Munich Air Crash in 1958 by donating three of their players, Derek Lewin, Bob Hardisty and Warren Bradley. In return in 1996, Manchester United played a friendly against Bishop Auckland to help raise money when the club was threatened with bankruptcy after a member of a rival team sued over an injury. In 2007 Manchester United donated floodlights to Bishop Auckland Football Club, which the club has added to their new ground.[144][145]

The adjacent village of West Auckland is notable for having been home to the team to win one of the first international footballing competitions, the Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy, sometimes referred to as The First World Cup. Its team of local coal miners won the cup in the Easter of 1909 and again in 1911, defeating the mighty Juventus in the final.[146] This story was portrayed in the 1982 television movie The World Cup - A Captain's Tale made by Tyne Tees Television and starring Dennis Waterman.[147] The cup itself was stolen from West Auckland Town F.C. in 1994 and a replica now resides in West Auckland working men's club.[146]

In terms of sports facilities, Woodhouse Close Leisure Complex, a council run leisure centre, has a 25-metre (82 ft) by 10-metre (33 ft) swimming pool and a 10-metre (33 ft) by 5-metre (16 ft) "learner" pool, as well as a gym, sauna, steam room and spa pool. Additionally, football pitches, tennis courts and bowling greens are provided at the Town Recreation Ground and Cockton Hill Recreation Ground. Henknowle Recreation Ground has a 5 a side pitch and a basketball court.[148]

Notable people

Stan Laurel of the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy lived in the town during his childhood, attending the town's King James 1st Grammar School.[149][150] His parents owned the now demolished Eden Theatre, which was located at the junction of Newgate Street and South Church Road.[151] In 2007, a Wetherspoons pub opened in the town named after Stan,[152] and in August 2008, a statue of Stan Laurel was unveiled on the site that his parent's theatre once occupied.[153]

One of the UK's most prolific serial killers, Mary Ann Cotton, lived in the nearby village of West Auckland. She was hanged at Durham Jail in 1873 for the murder of her stepson. However, it is believed that she could have been responsible for the deaths of at least 18 others.[154]

Roland Boys Bradford, who during World War I was awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery on 1 October 1916, and became Brigadier General, on 10 November 1917 at the age of 25 making him the youngest General in the British Army, was born in the nearby village of Witton Park.[155][156]

Sir Peter Soulsby, the current Mayor of Leicester was born in the town,[157] as well as the current MP for Mansfield, Alan Meale.[158]

Jeremiah Dixon, Astronomer and Surveyor of the Mason–Dixon Line,[159] footballer Charlie Wayman who played for Newcastle United, Middlesbrough and Southampton,[160] Actor Christopher Hancock, who played Charlie Cotton in EastEnders,[161] Leeds United goalkeeper Ross Turnbull,[162] Town planner Thomas Wilfred Sharp,[163] architect William Atkinson,[164] scientific instrument maker John Bird,[165] botanist Robert Kaye Greville[166] and Craig Raine, the poet and critic[167] were also all born in Bishop Auckland. Actor John Reed was born and spent his childhood in the nearby village of Close House.[168] Television producer Mark Phillips was born in Bishop Auckland before moving to Canada and eventually the United States.

In addition to Stan Laurel, the theologian and catholic priest Frederick William Faber,[169] nineteenth century industrialist William George Armstrong,[170] linguist Harold Orton,[171] 17th century politician James Craggs the Elder[172] and astronomer Thomas Wright[173] were all educated at the town's grammar school. Eds Chesters[174] drummer for The Bluetones[175] and Soho[176] is from Bishop Auckland.

See also

References

- ^ 2001 Census Profiles (Numbers) for Major Centres in County Durham (PDF). Durham County Council. Retrieved 29 August 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Town population 2011". Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Simpson 1991, p. 41

- ^ a b c Castle History, Auckland Castle, archived from the original on 28 September 2008, retrieved 25 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Fordyce 1857, p. 545

- ^ a b c d e Simpson, David, The North East England History Pages — Place Names, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b c d Fordyce 1857, p. 558

- ^ a b £2.4 m 'people's plan' to revive economy of market town, The Northern Echo, 9 August 2000, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b c d 2001 Census Profiles (Rates) for Major Centres in County Durham (PDF), Durham County Council, retrieved 6 June 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Make up of new unitary councils, BBC News, 1 April 2009, retrieved 6 June 2009

- ^ a b

Town Twinning, Wear Valley District Council, archived from the original on 4 December 2008, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Gelling, Margaret; W. F. H. Nicolaisen; Melville Richards (1970), The names of towns and cities in Britain, Batsford, p. 53

- ^ a b c Ekwall, Eilert (1960), The concise Oxford dictionary of place names (4 ed.), Oxford University Press, pp. 18–19

- ^ a b Bethany Fox, 'The P-Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland', The Heroic Age, 10 (2007), http://www.heroicage.org/issues/10/fox.html (appendix at http://www.heroicage.org/issues/10/fox-appendix.html).

- ^ a b c Echo Memories: Tides of change in the land of Canute, The Northern Echo, 20 July 2005, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b Lewis, Samuel (1831), A Topographical Dictionary of England, vol. 1, S. Lewis & co, pp. 108–112, retrieved 6 June 2009

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 21

- ^ Whellan 1856, p. 274

- ^ Hutchinson 2009, p. 5

- ^ Simpson 2002, p. 132

- ^ a b c Hutchinson 2005, p. 14

- ^ a b c Hutchinson 2009, p. 4

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 24313". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 24335". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 24309". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 22197". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 24317". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 23956". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Hutchinson 2009, p. 9

- ^ a b Laurie, Barbara, A Short History of Bishop Auckland, Bishop Auckland Town, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 26 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fordyce 1857, p. 543

- ^ a b Page, William (1905), A history of the County of Durham, Victoria History of the Counties of England, vol. 1, Constable, pp. 397–398

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 75

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, p. 15

- ^ a b Fordyce 1857, p. 547

- ^ Castle State Rooms (PDF), Auckland Castle, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2011, retrieved 16 September 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Lightfoot, Joseph Barber (1892), Leaders in the Northern Church: Sermons Preached in the Diocese of Durham, Macmillan, p. 140

- ^ Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1996), Historic Sites of County Durham, Sunderland: Albion, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-9525122-5-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Whellan 1856, p. 279

- ^ Fordyce 1857, p. 548

- ^ a b Fordyce 1857, p. 552

- ^ a b Simpson 1991, p. 25

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, p. 33

- ^ Whellan 1856, p. 276

- ^ a b Whellan 1856, p. 292

- ^ Hunt, Christopher John (1970), The lead miners of the Northern Pennines: in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 236, ISBN 978-0-7190-0380-6

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, pp. 76–77

- ^ Varley, E. A. (2004), "Barrington, Shute (1734–1826)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 September 2009

- ^ Soloway, R. A. (1969), Prelates and people: ecclesiastical social thought in England, 1783–1852, London: Taylor & Francis, p. 356, ISBN 978-0-7100-6331-1

- ^ Varley, E. A. (2004), "Mildert, William Van (1765–1836)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 September 2009

- ^ a b Brickstock, Richard (2007), Durham Castle: Fortress, Palace, College, Lindley: Jeremy Mills Publishing, pp. 52–53, ISBN 978-1-905217-24-3

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 56

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 48

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, p. 43

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 44

- ^ Fordyce 1857, pp. 567–569

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, pp. 82–84

- ^ a b Bulmer, Martin (1978), Mining and Social Change: Durham County in the Twentieth Century, London: Taylor & Francis, p. 145, ISBN 978-0-85664-509-9, retrieved 6 June 2009

- ^ Thematic Overview — Industrial, Durham County Council, archived from the original on 28 August 2008, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, p. 104

- ^ Railway works resurrected decades after closure blow, The Northern Echo, 10 August 2006, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ Simpson 1991, p. 1

- ^ A vision of Bishop Auckland UD, A vision of Britain, retrieved 28 August 2008

- ^ New Town Council for Bishop Auckland, Wear Valley District Council, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 26 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Durham unitary authority approved, BBC News, 25 July 2007, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ "Bishop Auckland", The Guardian, London: Guardian Unlimited, retrieved 6 June 2009

- ^ South Area, Durham Constabulary, archived from the original on 9 March 2009, retrieved 12 January 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Durham 1971–2000 averages, Met Office, archived from the original on 29 September 2007, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e UK 1971–2000 averages, Met Office, archived from the original on 5 July 2009, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Durham". CEDA Archive. Natural Centre for Environmental Data Analysis. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Durham (Durham) UK climate averages". Met Office. 1991–2020. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Burt, Stephen; Burt, Tim (2022). Durham Weather and Climate since 1841. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Tim Burt. "The weather at Durham in 2022". Durham Weather. Durham University. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Tim Burt. "The weather at Durham in 2023". Durham Weather. Durham University. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ 2001 Census Profiles (Numbers) for Major Centres in County Durham (PDF), Durham County Council, retrieved 29 August 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ Action plan aims to revive town fortunes, The Northern Echo, 26 October 2000, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ End of an era as charity shop pioneer pulls out, The Northern Echo, 13 June 2000, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ Bishop Auckland Town Centre Forum, Enterprising Britain, archived from the original on 3 April 2009, retrieved 26 September 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bishop Auckland Urban Renaissance Master Plan (PDF), Wear Valley District Council, June 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2008, retrieved 26 September 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebac turns its eyes to Far East, The Northern Echo, 16 November 2006, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b c Auckland Castle, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle West Mural Wall, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle Gatehouse, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle Chapel of St Peter, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle Screen Wall, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle Deer Shelter, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

•Auckland Castle Lodge, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009 - ^ a b c The Saxon Church, Saxon Green, Escomb, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ a b c Church of St Andrew, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ a b Church of St Helen, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ St Helen Hall, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ The Manor House, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ East Deanery, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ a b Newton Cap Bridge, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ http://www.durham.gov.uk/article/2011

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 20

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (7 October 2005), London should keep its hands off the treasures of the north, The Guardian, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ Bid to keep castle paintings in N-E, The Northern Echo, 14 May 2001, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b Simpson 1991, pp. 44–45

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 11

- ^ Bishop Auckland Town Hall, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ a b c Hutchinson 2005, pp. 121–122

- ^ a b Newton Cap Railway Viaduct, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 21 September 2009

- ^ Bridge leads to a rich vein of history, The Northern Echo, 19 February 2002, retrieved 8 August 2008

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 128

- ^ a b History of the Church, Escomb Saxon Church, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 30 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 70

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Elizabeth Williamson (1985), County Durham, The Buildings of England (2 ed.), Penguin, p. 411, ISBN 978-0-14-071009-0

- ^ Hutchinson 2009, p. 4

- ^ Carpenter, George W. (2004), "Hackworth, Timothy (1786–1850)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 26 January 2008

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 113

- ^ Go-Ahead will use green diesel, The Northern Echo, 18 February 2006, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ League Tables: King James I Community Arts College, BBC News, 11 January 2007, retrieved 26 August 2008

- ^ a b Secondary Schools in Durham, BBC News, 11 January 2007, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ League Tables: St John's Catholic School, BBC News, 10 January 2008, retrieved 10 January 2008

- ^ a b Secondary schools in Durham, BBC News, 10 January 2008, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ a b c League Tables: Secondary schools in Durham, BBC News, 15 January 2009, retrieved 15 January 2009

- ^ "King James I Community Arts College", BBC News, BBC News Online, 15 January 2009, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ a b c Secondary schools in Durham, BBC News, 13 January 2010, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ St John's RCVA Technology School and Sixth Form Centre, BBC News, 13 January 2010, retrieved 21 January 2010

- ^ a b Secondary schools in Durham, BBC News, 12 January 2011, retrieved 12 January 2011

- ^ Regional picture: GCSE results, BBC News, 26 January 2012, retrieved 9 February 2012

- ^ a b Secondary school league tables in Durham, BBC News, 26 January 2012, retrieved 9 February 2012

- ^ Guide to the secondary tables, BBC News, 12 January 2007, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ a b "Secondary schools in Darlington", BBC News, BBC News Online, 13 January 2010, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ League Tables: Secondary schools in Darlington, BBC News, 15 January 2009, retrieved 15 January 2009

- ^ "Secondary schools in Darlington", BBC News, BBC News Online, 10 January 2008, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ "Secondary schools in Darlington", BBC News, BBC News Online, 11 January 2007, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ Performance Tables - Local Authority results, Department for Education, retrieved 9 February 2012

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, pp. 75–77

- ^ Bishop Auckland General Hospital, County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, archived from the original on 4 December 2008, retrieved 30 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hospital changes start in summer, The Northern Echo, 7 May 2009, archived from the original on 24 July 2011, retrieved 6 June 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dates set for loss of Bishop Auckland hospital services, The Northern Echo, 10 September 2009, retrieved 18 September 2009

- ^ Ministers have given the go-ahead to 14 hospital building schemes, The Times, 4 July 1997

- ^ Hospital Records Database — Bishop Auckland General Hospital, The National Archives, retrieved 30 August 2008

- ^ Deadline set for move to £67 m hospital, The Northern Echo, 27 September 2001, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ About the Trust, County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, archived from the original on 30 December 2008, retrieved 18 January 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Royal visit to award-winning water treatment works, Northumbrian Water, 22 November 2005, retrieved 21 February 2009

- ^ Water Resources Drought Plan (PDF), Northumbrian Water, April 2008, pp. 19–20, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011, retrieved 21 February 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Archer, David; Chris Gibbins (1995), "Hydrological and species-specific responses to water transfers into the River Wear, northeast England." (PDF), Proceedings of a Boulder Symposium July 1995, IAHS: 207–218, retrieved 6 June 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bishop Auckland Methodist Church, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 23 September 2009

- ^ Church of St Anne, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 23 September 2009

- ^ Church of St Peter, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 23 September 2009

- ^ Archdeacons, Diocese of Durham, retrieved 23 September 2009

- ^ Diocesan Office, Diocese of Durham, archived from the original on 11 November 2009, retrieved 23 September 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Deanery of St William, Roman Catholic Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle, retrieved 23 September 2009

- ^ http://www.baptist.org.uk

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 110

- ^ Champs light the way for minnows, BBC News, 17 July 2007, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 24 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Amateurs help save the day after disaster, The Journal, 6 February 2008, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 24 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b World Cup winners prepare to tackle new kids on block, London: The Independent, 4 October 2006, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 9 August 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The World Cup — A Captain's Tale", Film & TV Database, BFI, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Leisure centres, swimming pools, multi-use games areas, Durham County Council, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 72

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 125

- ^ Hutchinson 2005, p. 91

- ^ Bishop Auckland Pubs – The Stanley Jefferson – a J D Wetherspoon pub, J D Wetherspoon, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Unveiling for Stan Laurel statue, BBC News, 30 August 2008, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 26 October 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gilliland, J (2004), "Cotton , Mary Ann (1832–1873)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 August 2008

- ^ Collins, Lesley (2004), "Bradford, Roland Boys (1892–1917)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ DLI Medal Collection — Roland Boys Bradford, DLI Museum, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Biography of Sir Peter Soulsby MP, Peter Soulsby, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alan Meale's CV, Alan Meale, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Howse, Derek (2004), "Dixon, Jeremiah (1733–1779)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Glanville, Brian (7 February 2006), Obituary — Charlie Wayman, London: The Guardian, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Obituary — Christopher Hancock, London: The Independent, 19 November 2004, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Soccerbase: Ross Turnbull, The Racing Post, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stansfield, K. M (2004), "Sharp, Thomas Wilfred (1901–1978)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 25 January 2008

- ^ Riddell, Richard (2004), "Atkinson, William (1774/75–1839)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ McConnell, Anita (2004), "Bird, John (1709–1776)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Foote, Yolanda (2004), "Greville, Robert Kaye (1794–1866)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Craig Raine, Contemporary Writers, The British Council, archived from the original on 22 November 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reed, John (2006), Nothing Whatever to Grumble At, Xlibris Corporation, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-4257-0255-7

- ^ Gilley, Sheridan (2004), "Faber, Frederick William (1814–1863)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Linsley, Stafford M. (2004), "Armstrong, William George", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Ellis, Stanley (2004), "Orton, Harold (1898–1975)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Handley, Stuart (2004), "Craggs, James, the elder", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ Knight, David (2004), "Wright, Thomas (1711–1786)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2008

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eds_Chesters

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bluetones

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soho_(band)

Bibliography

- Fordyce, William (1857), The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, A. Fullarton and Co., retrieved 6 June 2009

- Hutchinson, Tom (2009), South Church Memories of an ancient Auckland community, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Summerhill Books, ISBN 978-1-906721-15-2

- Hutchinson, Tom (2005), The History of Bishop Auckland, Seaham: The People's History, ISBN 978-1-902527-59-8

- Simpson, David A (1991), Prince Bishop country the people history and folklore of County Durham and the River Wear, North Pennine Publishing, ISBN 978-1-874617-00-6

- Simpson, David A (2002), Northern Roots, Sunderland: Business Education Publishers, ISBN 978-1-901888-35-5

- Whellan, William (1856), History, Topography, and Directory of the County Palatine of Durham, William Whellan and Co., retrieved 6 June 2009

External links