Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie | |

|---|---|

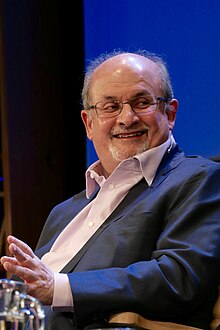

Rushdie at the 2016 Hay Festival | |

| Born | Ahmed Salman Rushdie 19 June 1947 Bombay, British India |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge |

| Genre | |

| Subject | |

| Spouse | Clarissa Luard

(m. 1976; div. 1987)Elizabeth West (m. 1997–2004) |

| Signature | |

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie[a] FRSL (born 19 June 1947) is a British Indian novelist and essayist. His second novel, Midnight's Children (1981), won the Booker Prize in 1981 and was deemed to be "the best novel of all winners" on two separate occasions, marking the 25th and the 40th anniversary of the prize. Much of his fiction is set on the Indian subcontinent. He combines magical realism with historical fiction; his work is concerned with the many connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern and Western civilizations.

His epic fourth novel, The Satanic Verses (1988), was the subject of a major controversy, provoking protests from Muslims in several countries. Death threats were made against him, including a fatwā calling for his assassination issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, on 14 February 1989. The British government put Rushdie under police protection.

In 1983 Rushdie was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the UK's senior literary organisation. He was appointed Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of France in January 1999.[5] In June 2007, Queen Elizabeth II knighted him for his services to literature.[6] In 2008, The Times ranked him thirteenth on its list of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945.[7]

Rushdie has lived in the United States. He was named Distinguished Writer in Residence at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute of New York University in 2015.[8] Earlier, he taught at Emory University. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2012, he published Joseph Anton: A Memoir, an account of his life in the wake of the controversy over The Satanic Verses.

Early life and family background

Ahmed Salman Rushdie[9] was born on 19 June 1947[10] in Bombay, then British India, into a Muslim family of Kashmiri descent.[2][11][12] He is the son of Anis Ahmed Rushdie, a Cambridge-educated lawyer-turned-businessman, and Negin Bhatt, a teacher. Rushdie has three sisters.[13] He wrote in his 2012 memoir that his father adopted the name Rushdie in honour of Averroes (Ibn Rushd).

He was educated at Cathedral and John Connon School in Bombay, Rugby School in Warwickshire, and King's College, University of Cambridge, where he read history.[10] His father Anis Rushdie was rusticated from the Indian Civil Service after the British government found out that he had changed his date of birth.[14]

Career

Copywriter

Rushdie worked as a copywriter for the advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather, where he came up with "irresistibubble" for Aero and "Naughty but Nice" for cream cakes, and for the agency Ayer Barker, for whom he wrote the memorable line "That'll do nicely" for American Express.[15] Collaborating with the musician Ronnie Bond, Rushdie wrote the words for an advertising record on behalf of the now defunct Burnley Building Society which was recorded at Good Earth Studios, London. The song was called "The Best Dreams" and was sung by George Chandler.[16] It was while he was at Ogilvy that he wrote Midnight's Children, before becoming a full-time writer.[17][18][19]

Major literary work

Rushdie's first novel, Grimus (1975), a part-science fiction tale, was generally ignored by the public and literary critics. His next novel, Midnight's Children (1981), catapulted him to literary notability. This work won the 1981 Booker Prize and, in 1993 and 2008, was awarded the Best of the Bookers as the best novel to have received the prize during its first 25 and 40 years.[20] Midnight's Children follows the life of a child, born at the stroke of midnight as India gained its independence, who is endowed with special powers and a connection to other children born at the dawn of a new and tumultuous age in the history of the Indian sub-continent and the birth of the modern nation of India. The character of Saleem Sinai has been compared to Rushdie.[21] However, the author has refuted the idea of having written any of his characters as autobiographical, stating, "People assume that because certain things in the character are drawn from your own experience, it just becomes you. In that sense, I’ve never felt that I’ve written an autobiographical character."[22]

After Midnight's Children, Rushdie wrote Shame (1983), in which he depicts the political turmoil in Pakistan, basing his characters on Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Shame won France's Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (Best Foreign Book) and was a close runner-up for the Booker Prize. Both these works of postcolonial literature are characterised by a style of magic realism and the immigrant outlook that Rushdie is very conscious of as a member of the Kashmiri diaspora.

Rushdie wrote a non-fiction book about Nicaragua in 1987 called The Jaguar Smile. This book has a political focus and is based on his first-hand experiences and research at the scene of Sandinista political experiments.

His most controversial work, The Satanic Verses, was published in 1988 (see section below).

In addition to books, Rushdie has published many short stories, including those collected in East, West (1994). The Moor's Last Sigh, a family epic ranging over some 100 years of India's history was published in 1995. The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999) presents an alternative history of modern rock music. The song of the same name by U2 is one of many song lyrics included in the book; hence Rushdie is credited as the lyricist. He also wrote Haroun and the Sea of Stories in 1990.[23]

Rushdie has had a string of commercially successful and critically acclaimed novels. His 2005 novel Shalimar the Clown received, in India, the prestigious Hutch Crossword Book Award, and was, in the UK, a finalist for the Whitbread Book Awards. It was shortlisted for the 2007 International Dublin Literary Award.[24]

In his 2002 non-fiction collection Step Across This Line, he professes his admiration for the Italian writer Italo Calvino and the American writer Thomas Pynchon, among others. His early influences included Jorge Luis Borges, Mikhail Bulgakov, Lewis Carroll, Günter Grass, and James Joyce. Rushdie was a personal friend of Angela Carter's and praised her highly in the foreword of her collection Burning your Boats.

His novel Luka and the Fire of Life was published in November 2010. Earlier that year, he announced that he was writing his memoirs,[25] entitled Joseph Anton: A Memoir, which was published in September 2012.

In 2012, Salman Rushdie became one of the first major authors to embrace Booktrack (a company that synchronises ebooks with customised soundtracks), when he published his short story "In the South" on the platform.[26]

Other activities

Rushdie has quietly mentored younger Indian (and ethnic-Indian) writers, influenced an entire generation of Indo-Anglian writers, and is an influential writer in postcolonial literature in general.[27] He has received many plaudits for his writings, including the European Union's Aristeion Prize for Literature, the Premio Grinzane Cavour (Italy), and the Writer of the Year Award in Germany and many of literature's highest honours.[28] Rushdie was the President of PEN American Center from 2004 to 2006 and founder of the PEN World Voices Festival.[29]

He opposed the British government's introduction of the Racial and Religious Hatred Act, something he writes about in his contribution to Free Expression Is No Offence, a collection of essays by several writers, published by Penguin in November 2005.

In 2007 he began a five-year term as Distinguished Writer in Residence at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, where he has also deposited his archives.[30]

In May 2008 he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[31]

In September 2015, he joined the New York University Journalism Faculty as a Distinguished Writer in Residence.[32]

Though he enjoys writing, Salman Rushdie says that he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. Even from early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood movies (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie includes fictional television and movie characters in some of his writings. He had a cameo appearance in the film Bridget Jones's Diary based on the book of the same name, which is itself full of literary in-jokes. On 12 May 2006, Rushdie was a guest host on The Charlie Rose Show, where he interviewed Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta, whose 2005 film, Water, faced violent protests. He appears in the role of Helen Hunt's obstetrician-gynecologist in the film adaptation (Hunt's directorial debut) of Elinor Lipman's novel Then She Found Me. In September 2008, and again in March 2009, he appeared as a panellist on the HBO program "Real Time with Bill Maher". Rushdie has said that he was approached for a cameo in Talladega Nights: "They had this idea, just one shot in which three very, very unlikely people were seen as NASCAR drivers. And I think they approached Julian Schnabel, Lou Reed, and me. We were all supposed to be wearing the uniforms and the helmet, walking in slow motion with the heat haze." In the end their schedules didn't allow for it.[33]

Rushdie collaborated on the screenplay for the cinematic adaptation of his novel Midnight's Children with director Deepa Mehta. The film was also called Midnight's Children.[34][35] Seema Biswas, Shabana Azmi, Nandita Das,[36] and Irrfan Khan participated in the film.[37] Production began in September 2010;[38] the film was released in 2012.[39]

Rushdie announced in June 2011 that he had written the first draft of a script for a new television series for the US cable network Showtime, a project on which he will also serve as an executive producer. The new series, to be called The Next People, will be, according to Rushdie, "a sort of paranoid science-fiction series, people disappearing and being replaced by other people." The idea of a television series was suggested by his US agents, said Rushdie, who felt that television would allow him more creative control than feature film. The Next People is being made by the British film production company Working Title, the firm behind such projects as Four Weddings and a Funeral and Shaun of the Dead.[40]

Rushdie is a member of the advisory board of The Lunchbox Fund,[41] a non-profit organisation which provides daily meals to students of township schools in Soweto of South Africa. He is also a member of the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America,[42] an advocacy group representing the interests of atheistic and humanistic Americans in Washington, D.C., and a patron of Humanists UK (formerly the British Humanist Association). He is also a Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.[43] In November 2010 he became a founding patron of Ralston College, a new liberal arts college that has adopted as its motto a Latin translation of a phrase ("free speech is life itself") from an address he gave at Columbia University in 1991 to mark the two-hundredth anniversary of the first amendment to the US Constitution.[44]

In 2017, Salman Rushdie appeared as himself in Episode 3 of Season 9 of Curb Your Enthusiasm,[45] sharing scenes with Larry David [46] to offer advice on how Larry should deal with the fatwa that has been ordered against him.

The Satanic Verses and the fatwā

The publication of The Satanic Verses in September 1988 caused immediate controversy in the Islamic world because of what was seen by some to be an irreverent depiction of Muhammad. The title refers to a disputed Muslim tradition that is related in the book. According to this tradition, Muhammad (Mahound in the book) added verses (Ayah) to the Qur'an accepting three goddesses who used to be worshipped in Mecca as divine beings. According to the legend, Muhammad later revoked the verses, saying the devil tempted him to utter these lines to appease the Meccans (hence the "Satanic" verses). However, the narrator reveals to the reader that these disputed verses were actually from the mouth of the Archangel Gabriel. The book was banned in many countries with large Muslim communities (13 in total: Iran, India, Bangladesh, Sudan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Thailand, Tanzania, Indonesia, Singapore, Venezuela, and Pakistan).

In response to the protests, on 22 January 1989 Rushdie published a column in The Observer that called Muhammad "one of the great geniuses of world history," but noted that Islamic doctrine holds Muhammad to be human, and in no way perfect. He held that the novel is not "an anti-religious novel. It is, however, an attempt to write about migration, its stresses and transformations."[47]

On 14 February 1989—Valentine's Day, and also the day of his close friend Bruce Chatwin's funeral—a fatwā ordering Rushdie's execution was proclaimed on Radio Tehran by Ayatollah Khomeini, the spiritual leader of Iran at the time, calling the book "blasphemous against Islam". (Chapter IV of the book depicts the character of an Imam in exile who returns to incite revolt from the people of his country with no regard for their safety.) A bounty was offered for Rushdie's death, and he was thus forced to live under police protection for several years. On 7 March 1989, the United Kingdom and Iran broke diplomatic relations over the Rushdie controversy.

When asked by a reporter for a response to the threat, Rushdie said, "I wish I had written a more critical book." Later, he wrote that he was "proud, then and always", of that statement; while he did not feel his book was especially critical of Islam, "a religion whose leaders behaved in this way could probably use a little criticism."[48]

The publication of the book and the fatwā sparked violence around the world, with bookstores firebombed. Muslim communities in several nations in the West held public rallies, burning copies of the book. Several people associated with translating or publishing the book were attacked, seriously injured, and even killed.[b] Many more people died in riots in some countries. Despite the danger posed by the fatwā, Rushdie made a public appearance at London's Wembley Stadium on 11 August 1993 during a concert by U2. In 2010, U2 bassist Adam Clayton recalled that "[lead vocalist] Bono had been calling Salman Rushdie from the stage every night on the Zoo TV tour. When we played Wembley, Salman showed up in person and the stadium erupted. You [could] tell from [drummer] Larry Mullen, Jr.'s face that we weren't expecting it. Salman was a regular visitor after that. He had a backstage pass and he used it as often as possible. For a man who was supposed to be in hiding, it was remarkably easy to see him around the place."[49]

On 24 September 1998, as a precondition to the restoration of diplomatic relations with the UK, the Iranian government, then headed by Mohammad Khatami, gave a public commitment that it would "neither support nor hinder assassination operations on Rushdie."[50][51]

Hardliners in Iran have continued to reaffirm the death sentence.[52] In early 2005, Khomeini's fatwā was reaffirmed by Iran's current spiritual leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, in a message to Muslim pilgrims making the annual pilgrimage to Mecca.[53] Additionally, the Revolutionary Guards declared that the death sentence on him is still valid.[54]

Rushdie has reported that he still receives a "sort of Valentine's card" from Iran each year on 14 February letting him know the country has not forgotten the vow to kill him and has jokingly referred it as "my unfunny Valentine"[55] in a sly reference to the song "My Funny Valentine". He said, "It's reached the point where it's a piece of rhetoric rather than a real threat."[56] Despite the threats on Rushdie personally, he said that his family has never been threatened, and that his mother, who lived in Pakistan during the later years of her life, even received outpourings of support. Rushdie himself has been prevented from entering Pakistan, however.[57]

A former bodyguard to Rushdie, Ron Evans, planned to publish a book recounting the behaviour of the author during the time he was in hiding. Evans claimed that Rushdie tried to profit financially from the fatwa and was suicidal, but Rushdie dismissed the book as a "bunch of lies" and took legal action against Evans, his co-author and their publisher.[58] On 26 August 2008, Rushdie received an apology at the High Court in London from all three parties.[59] A memoir of his years of hiding, Joseph Anton, was released on 18 September 2012. Joseph Anton was Rushdie's secret alias.[60]

In February 1997, Ayatollah Hasan Sane'i, leader of the bonyad panzdah-e khordad (Fifteenth of Khordad Foundation), reported that the blood money offered by the foundation for the assassination of Rushdie would be increased from $2 million to $2.5 million.[61] Then a semi-official religious foundation in Iran increased the reward it had offered for the killing of Rushdie from $2.8 million to $3.3 million.[62]

In November 2015, former Indian minister P. Chidambaram acknowledged that banning The Satanic Verses was wrong.[63][64] In 1998, Iran’s former president Mohammad Khatami proclaimed the fatwa “finished”; but it has never been officially lifted, and in fact has been reiterated several times by Ali Khamenei and other religious officials. Yet more money was added to the bounty in February 2016.[65]

Failed assassination attempt and Hezbollah's comments

On 3 August 1989, while Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh was priming a book bomb loaded with RDX explosive in a hotel in Paddington, Central London, the bomb exploded prematurely, destroying two floors of the hotel and killing Mazeh. A previously unknown Lebanese group, the Organization of the Mujahidin of Islam, said he died preparing an attack "on the apostate Rushdie". There is a shrine in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery for Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh that says he was "Martyred in London, 3 August 1989. The first martyr to die on a mission to kill Salman Rushdie." Mazeh's mother was invited to relocate to Iran, and the Islamic World Movement of Martyrs' Commemoration built his shrine in the cemetery that holds thousands of Iranian soldiers slain in the Iran–Iraq War.[50] During the 2006 Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah declared that "If there had been a Muslim to carry out Imam Khomeini's fatwā against the renegade Salman Rushdie, this rabble who insult our Prophet Mohammed in Denmark, Norway and France would not have dared to do so. I am sure there are millions of Muslims who are ready to give their lives to defend our prophet's honour and we have to be ready to do anything for that."[66]

International Guerillas

In 1990, soon after the publication of The Satanic Verses, a Pakistani film entitled International Gorillay (International Guerillas) was released that depicted Rushdie as a villain plotting to cause the downfall of Pakistan by opening a chain of casinos and discos in the country; he is ultimately killed at the end of the movie. The film was popular with Pakistani audiences, and it "presents Rushdie as a Rambo-like figure pursued by four Pakistani guerrillas".[67] The British Board of Film Classification refused to allow it a certificate, as "it was felt that the portrayal of Rushdie might qualify as criminal libel, causing a breach of the peace as opposed to merely tarnishing his reputation." This effectively prevented the release of the film in the UK. Two months later, however, Rushdie himself wrote to the board, saying that while he thought the film "a distorted, incompetent piece of trash", he would not sue if it were released. He later said, "If that film had been banned, it would have become the hottest video in town: everyone would have seen it". While the film was a great hit in Pakistan, it went virtually unnoticed elsewhere.[68]

2012 Jaipur Literature Festival events

Rushdie was due to appear at the Jaipur Literature Festival in January 2012.[69] However, he later cancelled his event appearance, and a further tour of India at the time citing a possible threat to his life as the primary reason.[70][71] Several days after, he indicated that state police agencies had lied, in order to keep him away, when they informed that paid assassins were being sent to Jaipur to kill him. Police contended that they were afraid Rushdie would read from the banned The Satanic Verses, and that the threat was real, considering imminent protests by Muslim organizations.[72]

Meanwhile, Indian authors Ruchir Joshi, Jeet Thayil, Hari Kunzru and Amitava Kumar abruptly left the festival, and Jaipur, after reading excerpts from Rushdie's banned novel at the festival. The four were urged to leave by organizers as there was a real possibility they would be arrested.[73] In India the import of the book is banned via customs.

A proposed video link session between Rushdie and the Jaipur Literature Festival was also cancelled at the last minute[74] after the government pressured the festival to stop it.[72] Rushdie returned to India to address a conference in Delhi on 16 March 2012.[75]

Al-Qaeda hit list

In 2010[76] Anwar al-Awlaki published an Al-Qaeda hit list in Inspire magazine, including Rushdie along with other figures claimed to have insulted Islam, including Ayaan Hirsi Ali, cartoonist Lars Vilks and three Jyllands-Posten staff members: Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose.[77][78][79] The list was later expanded to include Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier, who was murdered in a terror attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, along with 11 other people. After the attack, Al-Qaeda called for more killings.[80]

Rushdie expressed his support for Charlie Hebdo. He said, "I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity ... religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today."[81] In response to the attack, Rushdie commented on what he perceived as victim-blaming in the media, stating "You can dislike Charlie Hebdo. ... But the fact that you dislike them has nothing to do with their right to speak. The fact you dislike them certainly doesn't in any way excuse their murder".[82][83]

Knighthood

Rushdie was knighted for services to literature in the Queen's Birthday Honours on 16 June 2007. He remarked, "I am thrilled and humbled to receive this great honour, and am very grateful that my work has been recognised in this way."[84] In response to his knighthood, many nations with Muslim majorities protested. Parliamentarians of several of these countries condemned the action, and Iran and Pakistan called in their British envoys to protest formally. Controversial condemnation issued by Pakistan's Religious Affairs Minister Muhammad Ijaz-ul-Haq was in turn rebuffed by former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.[85] Ironically, their respective fathers Zia-ul-Haq and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had been earlier portrayed in Rushdie's novel Shame. Mass demonstrations against Rushdie's knighthood took place in Pakistan and Malaysia. Several called publicly for his death. Some non-Muslims expressed disappointment at Rushdie's knighthood, claiming that the writer did not merit such an honour and there were several other writers who deserved the knighthood more than Rushdie.[86][87]

Al-Qaeda condemned the Rushdie honour. The Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri is quoted as saying in an audio recording that UK's award for Kashmiri-born Rushdie was "an insult to Islam", and it was planning "a very precise response."[88]

Religious and political beliefs

Rushdie came from a liberal Muslim family[89] although he now identifies as an atheist. In a 2006 interview with PBS, Rushdie called himself a "hardline atheist".[90]

In 1989, in an interview following the fatwa, Rushdie said that he was in a sense a lapsed Muslim, though "shaped by Muslim culture more than any other", and a student of Islam.[22] In another interview the same year, he said, "My point of view is that of a secular human being. I do not believe in supernatural entities, whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim or Hindu."[91]

In 1990, in the "hope that it would reduce the threat of Muslims acting on the fatwa to kill him," he issued a statement claiming he had renewed his Muslim faith, had repudiated the attacks on Islam made by characters in his novel and was committed to working for better understanding of the religion across the world. However, Rushdie later said that he was only "pretending".[92]

His books often focus on the role of religion in society and conflicts between faiths and between the religious and those of no faith.

Rushdie advocates the application of higher criticism, pioneered during the late 19th century. Rushdie called for a reform in Islam[93] in a guest opinion piece printed in The Washington Post and The Times in mid-August 2005:

What is needed is a move beyond tradition, nothing less than a reform movement to bring the core concepts of Islam into the modern age, a Muslim Reformation to combat not only the jihadist ideologues but also the dusty, stifling seminaries of the traditionalists, throwing open the windows to let in much-needed fresh air. (…) It is high time, for starters, that Muslims were able to study the revelation of their religion as an event inside history, not supernaturally above it. (…) Broad-mindedness is related to tolerance; open-mindedness is the sibling of peace.

Rushdie is a critic of cultural relativism. He favours calling things by their true names and constantly argues about what is wrong and what is right. In an interview with Point of Inquiry in 2006[94] he described his view as follows:

We need all of us, whatever our background, to constantly examine the stories inside which and with which we live. We all live in stories, so called grand narratives. Nation is a story. Family is a story. Religion is a story. Community is a story. We all live within and with these narratives. And it seems to me that a definition of any living vibrant society is that you constantly question those stories. That you constantly argue about the stories. In fact the arguing never stops. The argument itself is freedom. It's not that you come to a conclusion about it. And through that argument you change your mind sometimes. … And that's how societies grow. When you can't retell for yourself the stories of your life then you live in a prison. … Somebody else controls the story. … Now it seems to me that we have to say that a problem in contemporary Islam is the inability to re-examine the ground narrative of the religion. … The fact that in Islam it is very difficult to do this, makes it difficult to think new thoughts.

Rushdie is an advocate of religious satire. He condemned the Charlie Hebdo shooting and defended comedic criticism of religions in a comment originally posted on English PEN where he called religions a medieval form of unreason. Rushdie called the attack a consequence of "religious totalitarianism" which according to him had caused "a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam".:[95]

Religion, a medieval form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today. I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. ‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.

He strongly supports feminism.[96]

Political background

In the 1980s in the United Kingdom, he was a supporter of the Labour Party and championed measures to end racial discrimination and alienation of immigrant youth and racial minorities.

Rushdie supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, leading the leftist Tariq Ali to label Rushdie and other "warrior writers" as "the belligerati'".[97] He was supportive of the US-led campaign to remove the Taliban in Afghanistan, which began in 2001, but was a vocal critic of the 2003 war in Iraq. He has stated that while there was a "case to be made for the removal of Saddam Hussein", US unilateral military intervention was unjustifiable.[98]

In the wake of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy in March 2006—which many considered an echo of the death threats and fatwā that followed publication of The Satanic Verses in 1989—Rushdie signed the manifesto Together Facing the New Totalitarianism, a statement warning of the dangers of religious extremism. The Manifesto was published in the left-leaning French weekly Charlie Hebdo in March 2006.[99]

In 2006, Rushdie stated that he supported comments by the then-Leader of the House of Commons Jack Straw, who criticised the wearing of the niqab (a veil that covers all of the face except the eyes). Rushdie stated that his three sisters would never wear the veil. He said, "I think the battle against the veil has been a long and continuing battle against the limitation of women, so in that sense I'm completely on Straw's side."[100]

Marxist critic Terry Eagleton, a former admirer of Rushdie's work, attacked him, saying he "cheered on the Pentagon's criminal ventures in Iraq and Afghanistan".[101] Eagleton subsequently apologised for having misrepresented Rushdie's views.[102] At an appearance at 92nd Street Y, Rushdie expressed his view on copyright when answering a question whether he had considered copyright law a barrier (or impediment) to free speech.

No. But that's because I write for a living, [laughs] and I have no other source of income, and I naïvely believe that stuff that I create belongs to me, and that if you want it you might have to give me some cash. ... My view is I do this for a living. The thing wouldn't exist if I didn't make it and so it belongs to me and don't steal it. You know. It's my stuff.[103]

When Amnesty International suspended human rights activist Gita Sahgal for saying to the press that she thought Amnesty International should distance itself from Moazzam Begg and his organisation, Rushdie said:

Amnesty … has done its reputation incalculable damage by allying itself with Moazzam Begg and his group Cageprisoners, and holding them up as human rights advocates. It looks very much as if Amnesty's leadership is suffering from a kind of moral bankruptcy, and has lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong. It has greatly compounded its error by suspending the redoubtable Gita Sahgal for the crime of going public with her concerns. Gita Sahgal is a woman of immense integrity and distinction.... It is people like Gita Sahgal who are the true voices of the human rights movement; Amnesty and Begg have revealed, by their statements and actions, that they deserve our contempt.[104]

Rushdie supported the election of Democrat Barack Obama for the American presidency and has often criticized the Republican party. In Indian politics, Rushdie has criticised the Bharatiya Janata Party and its Prime Minister Narendra Modi.[105]

Rushdie was involved in the Occupy Movement, both as a presence at Occupy Boston and as a founding member of Occupy Writers.

Rushdie is a supporter of gun control, blaming a shooting at a Colorado cinema in July 2012 on the American right to keep and bear arms.[106][107]

Rushdie supported the vote to remain in the EU during the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016.

Personal life

Rushdie has been married four times. He was married to his first wife Clarissa Luard[108] from 1976 to 1987 and fathered a son, Zafar (born 1979).[109] He left her in the mid-'80s for the Australian writer Robyn Davidson, to whom he was introduced by their mutual friend Bruce Chatwin.[110] His second wife was the American novelist Marianne Wiggins; they were married in 1988 and divorced in 1993. His third wife, from 1997 to 2004, was Elizabeth West; they have a son, Milan (born 1997). In 2004, he married the Indian American Padma Lakshmi, an actress, model, and host of the American reality-television show Top Chef. The marriage ended on 2 July 2007. In 2008, Rushdie was linked to Indian actress Riya Sen.[111]

In 1999, Rushdie had an operation to correct ptosis, a tendon condition that causes drooping eyelids and that, according to him, was making it increasingly difficult for him to open his eyes. "If I hadn't had an operation, in a couple of years from now I wouldn't have been able to open my eyes at all," he said.[112]

Since 2000, Rushdie has "lived mostly near Union Square" in New York City.[113] He is a fan of the English football club Tottenham Hotspur.[114]

Bibliography

Novels

- Grimus (1975)

- Midnight's Children (1981)

- Shame (1983)

- The Satanic Verses (1988)

- Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990)

- The Moor's Last Sigh (1995)

- The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999)

- Fury (2001)

- Shalimar the Clown (2005)

- The Enchantress of Florence (2008)

- Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights (2015)

- The Golden House (2017)[115]

Collections

- Homeless by Choice (1992, with R. Jhabvala and V. S. Naipaul)

- East, West (1994)

- The Best American Short Stories (2008, as Guest Editor)

Children's books

- Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990)

- Luka and the Fire of Life (2010)

Essays and non-fiction

- The Jaguar Smile: A Nicaraguan Journey (1987)

- "In Good Faith", Granta, 1990

- Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism, 1981–1991 (1992)

- "The Wizard of Oz: BFI Film Classics", BFI, 1992.

- "Mohandas Gandhi." Time, 13 April 1998.

- "Imagine There Is No Heaven.", extracted contribution from Letters to the Six Billionth World Citizen, a UN sponsored publication in English by Uitgeverij Podium, Amsterdam. The Guardian, 16 October 1999.

- Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992–2002 (2002)

- "The East is Blue" (2004)

- "A fine pickle." The Guardian, 28 February 2009.

- "In the South." Booktrack, 7 February 2012

- Joseph Anton: A Memoir (2012)

Awards

- Aristeion Prize (European Union)

- Arts Council Writers' Award

- Author of the Year (British Book Awards)

- Author of the Year (Germany)

- Booker Prize for Fiction

- Booker of Bookers for the best novel among the Booker Prize winners for Fiction awarded at its 25th anniversary (in 1993)

- The Best of the Booker awarded to commemorate the Booker Prize's 40th anniversary (in 2008), winner by public vote

- Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- English-Speaking Union Award

- Golden PEN Award[116]

- Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award (2014)[117]

- Honorary Patron, University Philosophical Society, Trinity College, Dublin.

- Hutch Crossword Book Award (India)

- India Abroad Lifetime Achievement Award (US)

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize (Fiction)

- Kurt Tucholsky Prize (Sweden)

- Mantua Prize (Italy)

- Norman Mailer Prize (US)

- James Joyce Award – University College Dublin

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology Honorary Professorship

- Chapman University Honorary Doctorate – Doctor of Humane Letters

- Outstanding Lifetime Achievement in Cultural Humanism (Harvard University)[118]

- PEN Pinter Prize (UK)[119]

- Premio Grinzane Cavour (Italy)

- Prix Colette (Switzerland)

- Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger

- St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates[120]

- State Prize for Literature (Austria)

- Whitbread Novel Award (twice)

- Writers' Guild of Great Britain Award for Children's Fiction

- University of Liège Doctor honoris causa

- Knight Bachelor Kt. 2007

See also

Notes

- ^ Pronounced /sælˈmɑːn ˈrʊʃdi/;[4] Template:Lang-ks, احمد سلمان رشدی.

- ^ See Hitoshi Igarashi, Ettore Capriolo, William Nygaard.

References

- ^ Tuttle, Kate (14 September 2017). "Salman Rushdie on the opulent realism of his new novel, 'The Golden House'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ a b Shalimar the Clown by Salman Rushdie. The Independent. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

Salman Rushdie the Kashmiri writes from the heart as he describes this dark incandescence.

- ^ Cristina Emanuela Dascalu (2007) Imaginary homelands of writers in exile: Salman Rushdie, Bharati Mukherjee, and V.S. Naipaul p.131

- ^ Pointon, Graham (ed.): BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names, 2nd edition. Oxford Paperbacks, 1990.

- ^ "Rushdie to Receive Top Literary Award", Chicago Tribune, 7 January 1999. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Birthday Honours List—United Kingdom", Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine The London Gazette, Issue 58358, Supplement No. 1, 16 June 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest British Writers Since 1945". The Times, 5 January 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010. Subscription required.

- ^ https://journalism.nyu.edu/about-us/faculty/distinguished-professionals-in-residence/

- ^ "Salman Rushdie claims victory in Facebook name battle". BBC News. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b British Council profile

- ^ Literary Encyclopedia: "Salman Rushdie". Retrieved 20 January 2008

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Salman Rushdie". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Salman Rushdie Discusses Creativity and Digital Scholarship with Erika Farr on YouTube

- ^ http://urdufigures.blogspot.co.uk/2016/09/rushdies-fathers-secret-humiliation-in.html

- ^ Ravikrishnan, Ashutosh. Salman Rushdie's Midnight Child Archived 15 April 2013 at archive.today. South Asian Diaspora. 25 July 2012.

- ^ After the Satanic Verses, the romantic lyrics

- ^ "Salman Rushdie biography Archived 1 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine", 2004, British Counsel. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ Negative because there is little positive to say, The Herald (Glasgow), George Birrell, 18 January 1997

- ^ "The birth pangs of Midnight’s Children", 1 April 2006

- ^ "Readers across the world agree that Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children is the Best of the Booker". Man Booker Prizes. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Saleem (Sinai) is not Salman (Rushdie)(although he marries a Padma) and Saleem's grandfather Dr Aadam Aziz is not him either, but there is a touching prescience at work here. In the opening pages of Midnight's Children, Dr Aziz while bending down on his prayer mat, bumps his nose on a hard tussock of earth. His nose bleeds and his eyes water and he decides then and there that never again will he bow before God or man. 'This decision, however, made a hole in him, a vacancy in a vital inner chamber, leaving him vulnerable to women and history.' Battered by a fatwa and one femme fatale too many, Salman would have some understanding of this. One more bouquet for Saleem Sinai 20 July 2008 by Nina Martyris, TNN. The Times of India

- ^ a b Meer, Ameena (1989). "Interview: Salman Rushdie". Bomb. 27 (Spring). Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Haroun and the sea of stories". WorldCat. OCLC. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "The 2007 Shortlist". Dublin City Public Libraries/International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Salman Rushdie at work on fatwa memoir", The Guardian, 12 October 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie Collaborates With Booktrack and the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Booktrack Launches A New E-reader Platform". Booktrack. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Demonizing Discourse in Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses at the Wayback Machine (archived 1 July 2000(Calendar))

- ^ Times of India Story on Rushdie's influence and awards Indiatimes.com

- ^ Rohter, Larry (7 May 2012). "PEN New York Times Rushdie, founder of PEN World Voices Festival". The New York Times.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie to Teach and Place His Archive at Emory University". Emory University Office of Media Relations. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Academicians Database Archived 4 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, American Academy of Arts and Letters. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ http://journalism.nyu.edu/about-us/news-post/2015/03/05/new-distinguished-writer-in-residence-salman-rushdie/

- ^ "Interview with Salman Rushdie". The Talks.

- ^ "Rushdie visits Mumbai for 'Midnight's Children' film". The Times of India. 11 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ SUBHASH K JHA, 13 January 2010, 12.00 am IST (13 January 2010). "I'm a film buff: Rushdie". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dreaming of Midnight's Children". The Indian Express. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Irrfan moves from Mira Nair to Deepa Mehta". Hindustan Times. 20 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tête-à-tête with Deepa Mehta". Hindustan Times. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Midnight's Children". Internet Movie Database. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (12 June 2011). "Salman Rushdie says TV drama series have taken the place of novels". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "The Lunchbox Fund".

- ^ "Salman Rushdie".

- ^ "Salman Rushdie Author and Patron of the BHA". British Humanist Association. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Collegium Ralstonianum apud Savannenses – Home". Ralston.ac. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Curb Your Enthusiasm".

- ^ "Larry David - IMDb".

- ^ Rushdie, Salman (22 January 1989). "Choice between light and dark". The Observer.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Rushdie, Salman. "The Disappeared". The New Yorker (17 September 2012), p. 50. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ U2 (July 2010). "Stairway to Devon − OK, Somerset!". Q. p. 101.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Anthony Loyd (8 June 2005). "Tomb of the unknown assassin reveals mission to kill Rushdie". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010.

- ^ "26 December 1990: Iranian leader upholds Rushdie fatwa". BBC News: On This Day. 26 December 1990. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Rubin, Michael (1 September 2006). "Can Iran Be Trusted?". The Middle East Forum: Promoting American Interests. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Webster, Philip, Ben Hoyle and Ramita Navai (20 January 2005). "Ayatollah revives the death fatwa on Salman Rushdie". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 3 March 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Iran adamant over Rushdie fatwa". BBC News. 12 February 2005. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Rushdie, Salman (15 February 1999). "My Unfunny Valentine". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Rushdie's term". Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ "Cronenberg meets Rushdie".

- ^ "Rushdie anger at policeman's book". BBC. 2 August 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Bodyguard apologises to Rushdie". BBC. 26 August 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Alison Flood (12 April 2012). "Salman Rushdie reveals details of fatwa memoir". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Buchta, Wilfried (2000). Who rules Iran? (PDF). The Washington Institute and The Konrad Adenauer. p. 6.

- ^ "Iran adds to reward for Salman Rushdie's death". The New York Post. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Govt's decision to ban Salman Rushdie's 'The Satanic Verses' was wrong, says P Chidambaram". Firstpost. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Rajiv Gandhi govt's ban on Salman Rushdie's 'Satanic Verses' wrong: Chidambaram". The Indian Express. 29 November 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Sian Cain. "Salman Rushdie: Iranian media raise more money for fatwa". the Guardian.

- ^ "Hezbollah: Rushdie death would stop Prophet insults". Agence France-Presse. 2 February 2006. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Joseph Bernard Tamney (2002). The Resilience of Conservative Religion: The Case of Popular, Conservative Protestant Congregations. Cambridge, UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

- ^ "International Guerrillas and Criminal Libel". Screenonline. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ 2012 Speakers Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Singh, Akhilesh Kumar (20 January 2012). "Salman Rushdie not to attend Jaipur Literature Festival". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie pulls out of Jaipur literature festival". BBC News. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ a b Singh, Akhilesh Kumar (24 January 2012). "Jaipur Literature Festival: Even a virtual Rushdie is unwelcome for Rajasthan govt". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ Singh, Akhilesh Kumar; Chowdhury, Shreya Roy (23 January 2012). "Salman Rushdie shadow on Jaipur Literature Festival: 4 authors who read from 'The Satanic Verses' sent packing". The Times of India. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Gill, Nikhila (24 January 2012). "Rushdie's Video Talk Is Canceled at India Literature Festival". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie to be a 'presence' at India conference". BBC News. 13 March 2012.

- ^ Scott Stewart (22 July 2010). "Fanning the Flames of Jihad". Security Weekly. Stratfor. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013.

Inspire also features a "hit list" that includes the names of people like Westergaard who were involved in the cartoon controversy as well as other targets such as Dutch politician Geert Wilders, who produced the controversial film Fitna in 2008

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dashiell Bennet (1 March 2013). "Look Who's on Al Qaeda's Most-Wanted List". The Wire.

- ^ Conal Urquhart. "Paris Police Say 12 Dead After Shooting at Charlie Hebdo". Time.

- ^ Victoria Ward. "Murdered Charlie Hebdo cartoonist was on al Qaeda wanted list". The Telegraph.

- ^ Lucy Cormack (8 January 2015). "Charlie Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier crossed off chilling al-Qaeda hitlist". The Age.

- ^ Time. 7 January 2015. salman rushdie response

- ^ Wilson Ring (15 January 2015). "Salman Rushdie, threatened over book, defends free speech". Associated Press.

- ^ Jack Thurston (15 January 2015). "After Paris Attacks, Salman Rushdie Defends Absolute Right of Free Speech While in Vermont". NECN. NBC Universal.

- ^ "15 June 2007 Rushdie knighted in honours list". BBC News. 15 June 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ Pierce, By Andrew. "Salman Rushdie is knighted by the Queen". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ 'Sir Rubbish: Does Rushdie Deserve a Knighthood', Times Higher Educational Supplement, 20 June 2007

- ^ "Protests spread to Malaysia over knighthood for Salman Rushdie". The New York Times. 20 June 2007. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ "10 July 2007 Al-Qaeda condemns Rushdie honour". BBC News. 10 July 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie". Biography.com. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ "Bill Moyers on Faith & Reason . Bill Moyers and Salman Rushdie . June 23, 2006 - PBS".

- ^ "Fact, faith and fiction". Far Eastern Economic Review. 2 March 1989. p. 11.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Rushdie: I was deranged when I embraced Islam", Daily News and Analysis, 6 April 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ "Muslims unite! A new Reformation will bring your faith into the modern era", The Times, 11 August 2005

- ^ "Salman Rushdie – Secular Values, Human Rights and Islamism". Point of Inquiry. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ^ Maddie Crum (7 January 2015). "Salman Rushdie Responds To Charlie Hebdo Attack, Says Religion Must Be Subject To Satire". Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ The Cut. "15 Male Celebrities Answer 'Are You a Feminist?' -- The Cut". The Cut.

- ^ Michael Mandel, How America Gets Away With Murder, Pluto Press, 2004, p. 60

- ^ "Letters, Salman Rushdie: No fondness for the Pentagon's politics | World news". The Guardian. London. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Writers issue cartoon row warning". BBC News. 1 March 2006. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Wagner, Thomas (10 October 2006). "Blair, Rushdie support former British foreign secretary who ignited veil debate". SignOnSanDiego.com. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ "The ageing punk of lit crit still knows how to spit – Times Online". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Terry Eagleton; Michael Kustow; Matthew Wright; Neil Morris (12 July 2007). "Letters: Writers challenging so-called civilisation". The Guardian. Scott Trust Limited. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Radio show Medierna broadcast on Sveriges Radio P1 on 31 January 2009.

- ^ Salman Rushdie's statement on Amnesty International, The Sunday Times, 21 February 2010

- ^ Burke, Jason (10 April 2014). "A Narendra Modi victory would bode ill for India, say Rushdie and Kapoor". The Guardian. Delhi. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie stirs up frenzy with tweets in response to Colorado multiplex shooting | New York Daily News". Daily News. New York. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Cheney, Alexandra (20 July 2012). "Salman Rushdie Sparks Furor With Colorado Theater Shooting Tweets – Speakeasy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Descended from the gentry family LUARD formerly of Byborough. See Burke's Landed Gentry 18th edn vol 1 (pub 1965) page 465 col 2

- ^ Free BMD website. Birth registered Q3 1979 Camden

- ^ Bruce Chatwin, letter to Ninette Dutton, 1 November 1984, in Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin, ed. Elizabeth Chatwin and Nicholas Shakespeare, p. 395

- ^ "Most men flirt with me: Riya Sen".

- ^ "Rushdie: New book out from under shadow of fatwa", CNN, 15 April 1999. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ Laura M. Holson, "From Exile to Everywhere", The New York Times, 23 March 2012 (online), 25 March 2012 (print). Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Collie, Ashley. "Shakespeare's Hotspur Would Be Proud to See His Namesake Tottenham Hotspur Leading Another British Invasion of America". HuffingtonPost.com. HPMG News. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ "The Golden House" by Salman Rushdie, Random House

- ^ "Golden Pen Award, official website". English PEN. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie får dansk litteraturpris på halv million". Politiken (in Danish). 12 June 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Greg Epstein (20 April 2007). "HNN #18: Salman Rushdie & Cultural Humanism". American Humanist Association and the Humanist Chaplaincy of Harvard University. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Julia (20 June 2014). "Salman Rushdie awarded the 2014 PEN/ Pinter Prize". English PEN. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ Website of St. Louis Literary Award

External links

- Official website

- Salman Rushdie at British Council: Literature

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Anant Kumar; Hans Dembowski (2010). "Polyphony and Contradictions Are Considered Indispensable in India". Qantara.de.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Salman Rushdie on Charlie Rose

- Salman Rushdie at IMDb

- Article archive at Journalisted

- Template:Worldcat id

- Salman Rushdie collected news and commentary at Al Jazeera English

- Salman Rushdie collected news and commentary at Dawn

- Salman Rushdie collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Salman Rushdie collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Jack Livings (Summer 2005). "Salman Rushdie, The Art of Fiction No. 186". The Paris Review.

- New York Times special feature on Rushdie, 1999

- Books by Salman Rushdie

- Salman Rushdie: A Chance of Lasting Video by Louisiana Channel

- Salman Rushdie at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Salman Rushdie

- 1947 births

- 20th-century British novelists

- 21st-century British novelists

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Best Screenplay Genie and Canadian Screen Award winners

- British atheists

- British Asian writers

- British Book Award winners

- British feminists

- British former Muslims

- British memoirists

- British expatriates in the United States

- Cathedral and John Connon School alumni

- Indian copywriters

- Critics of Islam

- Emory University faculty

- Fatwas

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Free speech activists

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients

- English people of Kashmiri descent

- English people of Indian descent

- Indian expatriates in Pakistan

- Knights Bachelor

- Living people

- Magic realism writers

- Man Booker Prize winners

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- People educated at Rugby School

- Writers from Mumbai

- Postcolonial literature

- Postmodern writers

- Opposition to Islam in the United Kingdom

- British social commentators

- Atheism in the United Kingdom

- British atheism activists

- Indian emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Male feminists

- 20th-century Indian essayists

- 21st-century Indian essayists

- 20th-century Indian novelists

- 21st-century Indian novelists

- 20th-century atheists

- 21st-century atheists

- Novelists from Maharashtra

- Screenwriters from Mumbai

- Film producers from Mumbai

- Male actors from Mumbai

- 21st-century Indian male actors

- Indian television writers

- 21st-century Indian dramatists and playwrights

- Former Muslims turned agnostics or atheists