History of spectroscopy

The history of spectroscopy began in the 17th century. New designs in optics, specifically prisms, enabled systematic observations of the solar spectrum. Isaac Newton first applied the word spectrum to describe the rainbow of colors that combine to form white light. During the early 1800s, Joseph von Fraunhofer conducted experiments with dispersive spectrometers that enabled spectroscopy to become a more precise and quantitative scientific technique. Since then, spectroscopy has played and continues to play a significant role in chemistry, physics and astronomy.

Origins and experimental development

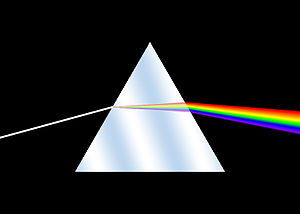

The Romans were already familiar with the ability of a prism to generate a rainbow of colors.[1] Newton is traditionally regarded as the founder of spectroscopy, but he was not the first man of science who studied and reported on the solar spectrum. The works of Athanasius Kircher (1646), Jan Marek Marci (1648), Robert Boyle (1664), and Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1665), predate Newton's optics experiments (1666–1672).[2] Newton published his experiments and theoretical explanations of dispersion of light in his 'Opticks'. His experiments demonstrated that white light could be split up into component colors by means of a prism and that these components could be recombined to generate white light. He demonstrated that the prism is not imparting or creating the colors but rather separating constituent parts of the white light.[3] Newton's corpuscular theory of light was gradually succeeded by the wave theory. It was not until the 19th century that the quantitative measurement of dispersed light was recognized and standardized. As with many subsequent spectroscopy experiments, Newton's sources of white light included flames and stars, including our own sun. Subsequent experiments with prisms provided the first indications that spectra were associated uniquely with chemical constituents. Scientists observed the emission of distinct patterns of colour when salts were added to alcohol flames.[4]

Early 19th Century (1800 - 1829)

In 1802, William Hyde Wollaston built a spectrometer, improving on Newton's model, that included a lens to focus the Sun’s spectrum on a screen. Upon use, Wollaston realized that the colors were not spread uniformly, but instead had missing patches of colors, which appeared as dark bands in the sun's spectrum.[5] At the time, Wollaston believed these lines to be natural boundaries between the colors, but this hypothesis was later ruled out in 1815 by Fraunhofer's work.[6]

Joseph von Fraunhofer made a significant experimental leap forward by replacing a prism with a diffraction grating as the source of wavelength dispersion. Fraunhofer built off the theories of light interference developed by Thomas Young, François Arago and Augustin-Jean Fresnel. He conducted his own experiments to demonstrate the effect of passing light through a single rectangular slit, two slits, and so forth, eventually developing a means of closely spacing thousands of slits to form a diffraction grating. The interference achieved by a diffraction grating both improves the spectral resolution over a prism and allows for the dispersed wavelengths to be quantified. Fraunhofer's establishment of a quantified wavelength scale paved the way for matching spectra observed in multiple laboratories, from multiple sources (flames and the sun) and with different instruments. Fraunhofer made and published systematic observations of the solar spectrum, and the dark bands he observed and specified the wavelengths of are still known as Fraunhofer lines.[7]

Throughout the early 1800s, a number of scientists pushed the techniques and understanding of spectroscopy forward.[5] [8] In the 1820s both John Herschel and William H. F. Talbot made systematic observations of salts using flame spectroscopy.[9]

Mid 19th Century (1830 - 1869)

In 1835, Charles Wheatstone reported that different metals could be easily distinguished by the different bright lines in the emission spectra of their sparks, thereby introducing an alternative mechanism to flame spectroscopy.[10] In 1849, J. B. L. Foucault experimentally demonstrated that absorption and emission lines appearing at the same wavelength are both due to the same material, with the difference between the two originating from the temperature of the light source.[11] In 1853, the Swedish physicist Anders Jonas Ångström presented observations and theories about gas spectra in his work: Optiska Undersökningar to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Ångström postulated that an incandescent gas emits luminous rays of the same wavelength as those it can absorb. Ångström was unaware of Foucalt's experimental results. At the same time George Stokes and William Thomson (Kelvin) were discussing similar postulates.[11] Ångström also measured the emission spectrum from hydrogen later labeled the Balmer lines.[12] In 1854 and 1855, David Alter published observations on the spectra of metals and gases, including an independent observation of the Balmer lines of hydrogen.[13]

The systematic attribution of spectra to chemical elements began in the 1860s with the work of German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff and chemist Robert Bunsen. Bunsen and Kirchhoff applied the optical techniques of Fraunhofer, Bunsen's improved flame source and a highly systematic experimental procedure to a detailed examination of the spectra of chemical compounds. They established the linkage between chemical elements and their unique spectral patterns. In the process, they established the technique of analytical spectroscopy. In 1860, they published their findings on the spectra of eight elements and identified these elements' presence in several natural compounds.[14] [15] They demonstrated that spectroscopy could be used for trace chemical analysis and several of the chemical elements they discovered were previously unknown. Kirchhoff and Bunsen also definitively established the link between absorption and emission lines, including attributing solar absorption lines to particular elements based on their corresponding spectra.[16] Kirchhoff went on to contribute fundamental research on the nature of spectral absorption and emission, including what is now known as Kirchhoff's Law of Thermal Radiation. Kirchhoff's applications of this law to spectroscopy are captured in three laws of spectroscopy:

- An incandescent solid, liquid or gas under high pressure emits a continuous spectrum.

- A hot gas under low pressure emits a "bright-line" or emission-line spectrum.

- A continuous spectrum source viewed through a cool, low-density gas produces an absorption-line spectrum.

In the 1860s the husband-and-wife team of William and Margaret Huggins used spectroscopy to determine that the stars were composed of the same elements as found on earth. They also used the non-relativistic Doppler shift (redshift) equation on the spectrum of the star Sirius in 1868 to determine its axial speed.[17] They were the first to take a spectrum of a planetary nebula when the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543) was analyzed.[18] Using spectral techniques, they were able to distinguish nebulae from galaxies.

Late 19th Century (1870 - 1899)

Johann Balmer discovered in 1885 that the four visible lines of hydrogen were part of a series that could be expressed in terms of integers. This was followed a few years later by the Rydberg formula, which described additional series of lines.

Meanwhile, the substantial summary of past experiments performed by Maxwell (1873), resulted in his equations of electromagnetic waves.

In 1895, the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovers and extensively studies X-rays, which are later used in X-ray spectroscopy. One year later, in 1896, French physicist Antoine Henri Becquerel discovers radioactivity, and Dutch physicist Pieter Zeeman observes spectral lines being split by a magnetic field.[5]

Development of quantum mechanics

In the early twentieth century, spectroscopy research contributed significantly to the development of quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics provided an explanation of and theoretical framework for understanding spectroscopic observations.

Infrared and Raman spectroscopy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2016) |

Laser spectroscopy

The laser, and its predecessor the maser, were invented by spectroscopists. Lasers have gone on to significantly advance experimental spectroscopy.

See also

References

- ^ Brand, John C. D. (1995). Lines of Light: The Sources of Dispersive Spectroscopy, 1800 - 1930. Gordon and Breach Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 2884491627.

- ^ Burns, Thorburn (1987). "Aspects of the development of colorimetric analysis and quantitative molecular spectroscopy in the ultraviolet-visible region". In Burgess, C.; Mielenz, K. D. (eds.). Advances in Standards and Methodology in Spectrophotometry. Burlington: Elsevier Science. p. 1. ISBN 9780444599056.

- ^ "The Era of Classical Spectroscopy". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Brand, p. 58

- ^ a b c "A Timeline of Atomic Spectroscopy". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ OpenStax Astronomy, "Spectroscopy in Astronomy". OpenStax CNX. Sep 29, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/1f92a120-370a-4547-b14e-a3df3ce6f083@3

- ^ Brand, pp. 37-42

- ^ George Gore (1878). The Art of Scientific Discovery: Or, The General Conditions and Methods of Research in Physics and Chemistry. Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 179.

- ^ Brand, p. 59

- ^ Brian Bowers (2001). Sir Charles Wheatstone FRS: 1802-1875 (2nd ed.). IET. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-85296-103-2.

- ^ a b Brand, pp. 60-62

- ^ Wagner, H. J. (2005). "Early Spectroscopy and the Balmer Lines of Hydrogen". Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (3): 380. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82..380W. doi:10.1021/ed082p380.1. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Retcofsky, H. L. (2003). "Spectrum Analysis Discoverer?". Journal of Chemical Education. 80 (9): 1003. Bibcode:2003JChEd..80.1003R. doi:10.1021/ed080p1003.1. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1860). "Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen". Annalen der Physik. 180 (6): 161–189. Bibcode:1860AnP...186..161K. doi:10.1002/andp.18601860602. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1901). "Chemical Analysis By Spectral Observations". In Brace, D. B. (ed.). The Laws of Radiation and Absorption: Memoirs by Prévost, Stewart, Kirchhoff, and Kirchhoff and Bunsen. New York: American Book Company. pp. 99–125.

- ^ Brand, pp. 63-64

- ^ Singh, Simon (2005). Big Bang. Harper Collins. pp. 238–246. ISBN 9780007162215.

- ^ Kwok, Sun (2000). "Chapter 1: History and overview". The Origin and Evolution of Planetary Nebulae. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 0-521-62313-8.