2001 Mars Odyssey

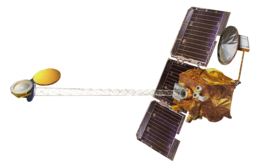

Artist's impression of the Mars Odyssey spacecraft | |

| Mission type | Mars orbiter |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 2001-014A |

| SATCAT no. | 26734 |

| Website | mars |

| Mission duration | Elapsed: 23 years, 8 months and 19 days from launch 23 years, 2 months and 2 days at Mars (8238 sols) En route: 6 months, 17 days Primary mission: 32 months (1007 sols) Extended mission: 20 years, 4 months and 1 day (7229 sols) elapsed |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin |

| Launch mass | 758 kilograms (1,671 lb) |

| Dry mass | 376.3 kilograms (830 lb) |

| Power | 750 W |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 7 April 2001, 15:02:22 UTC |

| Rocket | Delta II 7925-9.5 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17A |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Areocentric |

| Semi-major axis | 3,785 kilometers (2,352 mi) |

| Eccentricity | 0.0115 |

| Periareion altitude | 201 kilometers (125 mi) |

| Apoareion altitude | 500 kilometers (310 mi) |

| Inclination | 93.2 degrees |

| Period | 117.84 minutes |

| Mars orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | 24 October 2001, 02:18:00 UTC MSD 45435 12:21 AMT |

| |

2001 Mars Odyssey is a robotic spacecraft orbiting the planet Mars. The project was developed by NASA, and contracted out to Lockheed Martin, with an expected cost for the entire mission of US$297 million. Its mission is to use spectrometers and a thermal imager to detect evidence of past or present water and ice, as well as study the planet's geology and radiation environment.[1] It is hoped that the data Odyssey obtains will help answer the question of whether life existed on Mars and create a risk-assessment of the radiation that future astronauts on Mars might experience. It also acts as a relay for communications between the Mars Exploration Rovers, Mars Science Laboratory, and previously the Phoenix lander to Earth. The mission was named as a tribute to Arthur C. Clarke, evoking the name of 2001: A Space Odyssey.[2]

Odyssey was launched April 7, 2001, on a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, and reached Mars orbit on October 24, 2001, at 02:30 UTC (October 23, 19:30 PDT, 22:30 EDT).[3]

By December 15, 2010, it broke the record for longest serving spacecraft at Mars, with 3,340 days of operation.[4] It is currently in a polar orbit around Mars with a semi-major axis of about 3,800 km or 2,400 miles. It has enough propellant to function until 2025.

Overview

On May 28, 2002 (sol 210), NASA reported that Odyssey's GRS instrument had detected large amounts of hydrogen, a sign that there must be ice lying within a meter of the planet's surface, and proceeded to map the distribution of water below the shallow surface.[5] The orbiter also discovered vast deposits of bulk water ice near the surface of equatorial regions.[6]

Odyssey has also served as the primary means of communications for NASA's Mars surface explorers in the past decade, up to the Curiosity rover. By December 15, 2010, it broke the record for longest serving spacecraft at Mars, with 3,340 days of operation, claiming the title from NASA's Mars Global Surveyor.[4] It currently holds the record for the longest-surviving continually active spacecraft in orbit around a planet other than Earth, ahead of the Pioneer Venus Orbiter (served 14 years[7]) and the Mars Express (serving over 14 years), at 23 years, 2 months and 2 days.

Naming

Mars Odyssey was originally a component of the Mars Surveyor 2001 program, and was named the Mars Surveyor 2001 Orbiter.[citation needed] It was intended to have a companion spacecraft known as Mars Surveyor 2001 Lander, but the lander mission was canceled in May 2000 following the failures of Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander in late 1999. Subsequently, the name 2001 Mars Odyssey was selected for the orbiter as a specific tribute to the vision of space exploration shown in works by Arthur C. Clarke, including 2001: A Space Odyssey. The music from Mythodea by Greek composer Vangelis was used as the theme music for the mission.[citation needed]

In August 2000, NASA solicited candidate names for the mission. Out of 200 names submitted, the committee chose Astrobiological Reconnaissance and Elemental Surveyor, abbreviated ARES (a tribute to Ares, the Greek god of war). Faced with criticism that this name was not very compelling, and too aggressive, the naming committee reconvened. The candidate name "2001 Mars Odyssey" had earlier been rejected because of copyright and trademark concerns. However, NASA e-mailed Arthur C. Clarke in Sri Lanka, who responded that he would be delighted to have the mission named for his books, and he had no objections. On September 20, NASA associate administrator Ed Weiler wrote to the associate administrator for public affairs recommending a name change from ARES to 2001 Mars Odyssey. Peggy Wilhide then approved the name change.[8][9]

Scientific instruments

The three primary instruments Odyssey uses are the:

- Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS).[10]

- Gamma Ray Spectrometer (GRS),[11] includes the High Energy Neutron Detector (HEND), provided by Russia. GRS is a collaboration between University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Lab., the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Russia's Space Research Institute.

- Mars Radiation Environment Experiment (MARIE).

Mission

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

Mars Odyssey launched from Cape Canaveral on April 7, 2001, and arrived at Mars about 200 days later on October 24. The spacecraft's main engine fired in order to decelerate, which allowed it to be captured into orbit around Mars. Odyssey then spent about three months aerobraking, using friction from the upper reaches of the Martian atmosphere to gradually slow down and reduce and circularize its orbit. By using the atmosphere of Mars to slow the spacecraft in its orbit rather than firing its engine or thrusters, Odyssey was able to save more than 200 kilograms (440 lb) of propellant. This reduction in spacecraft weight allowed the mission to be launched on a Delta II 7925 launch vehicle, rather than a larger, more expensive launcher.[12] Aerobraking ended in January, and Odyssey began its science mapping mission on February 19, 2002. Odyssey's original, nominal mission lasted until August 2004, but repeated mission extensions have kept the mission active.[13]

About 85% of images and other data from NASA's twin Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, have reached Earth via communications relay by Odyssey. Odyssey continues to receive transmissions from the surviving rover, Opportunity, every day. The orbiter helped analyze potential landing sites for the rovers and performed the same task for NASA's Phoenix mission, which landed on Mars in May 2008. Odyssey aided NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which reached Mars in March 2006, by monitoring atmospheric conditions during months when the newly arrived orbiter used aerobraking to alter its orbit into the desired shape.

Odyssey is in a Sun-synchronous orbit, which provides consistent lighting for its photographs. On September 30, 2008 (sol 2465) the spacecraft altered its orbit to gain better sensitivity for its infrared mapping of Martian minerals. The new orbit eliminated the use of the gamma ray detector, due to the potential for overheating the instrument at the new orbit.

The payload's MARIE radiation experiment stopped taking measurements after a large solar event bombarded the Odyssey spacecraft on October 28, 2003. Engineers believe the most likely cause is that a computer chip was damaged by a solar particle smashing into the MARIE computer board.

One of the orbiter's three flywheels failed in June 2012. However, Odyssey's design included a fourth flywheel, a spare carried against exactly this eventuality. The spare was spun up and successfully brought into service. Since July 2012, Odyssey has been back in full, nominal operation mode following three weeks of 'safe' mode on remote maintenance.[14]

On February 11, 2014, mission control accelerated Odyssey's drift toward a morning-daylight orbit to "enable observation of changing ground temperatures after sunrise and after sunset in thousands of places on Mars". The orbital change occurred gradually until November 2015.[15] Those observations could yield insight about the composition of the ground and about temperature-driven processes, such as warm seasonal flows observed on some slopes, and geysers fed by spring thawing of carbon dioxide (CO2) ice near Mars' poles.[15]

On October 19, 2014, NASA reported that the Mars Odyssey Orbiter,[16] as well as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter[17] and MAVEN,[18] were healthy after the Comet Siding Spring flyby.[19][20]

In 2010, a spokesman for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory stated that Odyssey could continue operating until at least 2016.[21] This estimate has since been extended until 2025.[22]

Water on Mars

By 2008, Mars Odyssey had mapped the basic distribution of water below the shallow surface.[23] The ground truth for its measurements came on July 31, 2008, when NASA announced that the Phoenix lander confirmed the presence of water on Mars,[24] as predicted in 2002 based on data from the Odyssey orbiter. The science team is trying to determine whether the water ice ever thaws enough to be available for microscopic life, and if carbon-containing chemicals and other raw materials for life are present.

The orbiter also discovered vast deposits of bulk water ice near the surface of equatorial regions.[6] Evidence for equatorial hydration is both morphological and compositional and is seen at both the Medusae Fossae formation and the Tharsis Montes.[6]

Odyssey and Curiosity

Mars Odyssey's THEMIS instrument was used to help select a landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL).[25] Several days before MSL's landing in August 2012, Odyssey's orbit was altered to ensure that it would be able to capture signals from the rover during its first few minutes on the Martian surface.[26] Odyssey also acts as a relay for UHF radio signals from the (MSL) rover Curiosity.[26] Because Odyssey is in a Sun-synchronous orbit, it consistently passes over Curiosity's location at the same two times every day, allowing for convenient scheduling of contact with Earth.

See also

References

- ^ "Mars Odyssey Goals". NASA JPL.

- ^ "Mars Odyssey: Overview". JPL, CIT. Archived from the original on 2011-09-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Beatty, J. Kelly (2012-05-24). "Mars Odyssey Arrives". Sky and Telescope. Sky Publishing.

- ^ a b "NASA's Odyssey Spacecraft Sets Exploration Record on Mars". Press Releases. JPL, NASA. 2010-12-15. Archived from the original on 2011-04-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "January, 2008: Hydrogen Map". Lunar & Planetary Lab at The University of Arizona.

- ^ a b c Equatorial locations of water on Mars: Improved resolution maps based on Mars Odyssey Neutron Spectrometer data (PDF). Jack T. Wilson, Vincent R. Eke, Richard J. Massey, Richard C. Elphic, William C. Feldman, Sylvestre Maurice, Luıs F. A. Teodoroe. Icarus, 299, 148-160. January 2018.

- ^ Pioneer Venus 1: In Depth. NASA.

- ^ Hubbard, Scott (2011). Exploring Mars: Chronicles from a Decade of Discovery. University of Arizona Press. pp. 149–51. ISBN 978-0-8165-2896-7.

- ^ "It's "2001 Mars Odyssey" for NASA's Next Trip to the Red Planet" (Press release). NASA HQ/JPL. 2000-09-28. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ^ Christensen, P. R.; Jakosky, B. M.; Kieffer, H. H.; Malin, M. C.; McSween Jr., H. Y.; Nealson, K.; Mehall, G. L.; Silverman, S. H.; Ferry, S.; Caplinger, M.; Ravine, M. (2004). "The Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) for the Mars 2001 Odyssey Mission". Space Science Reviews. 110 (1–2): 85. Bibcode:2004SSRv..110...85C. doi:10.1023/B:SPAC.0000021008.16305.94.

- ^ Boynton, W.V.; Feldman, W.C.; Mitrofanov, I.G.; Evans, L.G.; Reedy, R.C.; Squyres, S.W.; Starr, R.; Trombka, J.I.; d'Uston, C.; Arnold, J.R.; Englert,, P.A.J.; Metzger, A.E.; Wänke, H.; Brückner, J.; Drake, D.M.; Shinohara, C.; Fellows, C.; Hamara, D.K.; Harshman, K.; Kerry, K.; Turner, C.; Ward1, M.; Barthe, H.; Fuller, K.R.; Storms, S.A.; Thornton, G.W.; Longmire, J.L.; Litvak, M.L.; Ton'chev, A.K. (2004). "The Mars Odyssey Gamma-Ray Spectrometer Instrument Suite". Space Science Reviews. 110 (1–2): 37. Bibcode:2004SSRv..110...37B. doi:10.1023/B:SPAC.0000021007.76126.15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mars Odyssey: Newsroom". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ "Mission Timeline - Mars Odyssey". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ "Longest-Lived Mars Orbiter Is Back in Service". Status Reports. JPL. 2012-06-27. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Staff (2014-02-12). "NASA Moves Longest-Serving Mars Spacecraft for New Observations". Press Releases. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (October 19, 2014). "NASA's Mars Odyssey Orbiter Watches Comet Fly Near". NASA. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (October 19, 2014). "NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Studies Comet Flyby". NASA. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Jones, Nancy; Steigerwald, Bill; Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (October 19, 2014). "NASA's MAVEN Studies Passing Comet and Its Effects". NASA. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne; Jones, Nancy; Steigerwald, Bill (October 19, 2014). "All Three NASA Mars Orbiters Healthy After Comet Flyby". NASA. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ France-Presse, Agence (October 19, 2014). "A Comet's Brush With Mars". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Kremer, Ken (2010-12-13). "The Longest Martian Odyssey Ever". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2010-12-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "THEMIS makes 60,000 orbits of Red Planet | Mars Odyssey Mission THEMIS". themis.asu.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ^ "January, 2008: Hydrogen Map". Lunar & Planetary Lab at The University of Arizona.

- ^ "Confirmation of Water on Mars". Phoenix Mars Lander. NASA. 2008-06-20. Archived from the original on 2008-07-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "THEMIS Support for MSL Landing Site Selection". THEMIS. Arizona State University. 2006-07-28. Archived from the original on 2006-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gold, Scott (2012-08-07). "Curiosity's perilous landing? 'Cleaner than any of our tests'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2012-08-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Mars Odyssey site

- 2001 Mars Odyssey Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Sky & Telescope: "Mars Odyssey Pays Early Dividends"

- BBC News story on Mars Odyssey observations of apparent ice deposits

- Mars Trek - Shows present overhead position of Mars Odyssey