Spanish Romanesque

Spanish Romanesque to designate the spatial division of the Romanesque art corresponding to Hispanic-Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in the 11th and 12th centuries. However, its stylistic features are essentially common to the European Romanesque, and in the particular differentiated between areas that usually subdivided. The southern half of the peninsula lacks of Romanesque art since remained under Muslim rule (Andalusi art). The Romanesque in the central area of the peninsula is low and late, with virtually no presence at south of the Ebro and the Tagus; It is the northern third peninsular the area where are concentrated the Romanesque buildings. In view of the fact that the Romanesque is introduced into the peninsula from east to west, for the purposes of its study, the regional delimitation is done in the same direction: in "eastern kingdoms" (the kingdoms or Pyrenean areas: Catalan Romanesque, Aragonese Romanesque and Navarrese Romanesque), and "western kingdoms" (Castilian-Leonese Romanesque, Asturian Romanesque, Galician Romanesque and Portuguese Romanesque).

The First Romanesque or Lombard Romanesque has especially presence in Catalonia, while the full Romanesque spread from the foundations of the Order of Cluny along the axis of Camino de Santiago. The late-romanesque continues in the 13th century, especially in rural buildings.[1]

Architecture

From the 11th century the European artistic influence (especially Burgundian - Cluny - and Lombard monasteries - Lombard arches -) was superimposed on local artistic traditions ( called as "Pre-Romanesque - Visigothic art, Asturian art, Mozarabic art or Repoblación art) and Andalusi art or Hispanic Muslim) and lived with the so-called Mudéjar Romanesque (or "Romanesque of brick", dominant in some areas, such as the center of the Northern Plateau -from Sahagún to Cuéllar-, Toledo or Teruel) giving rise to an art of strong personality.

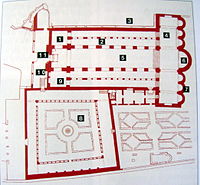

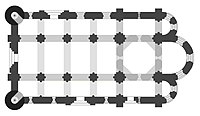

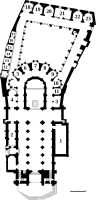

The chronology in the penetration of architectural forms is visible in a display from east to west, being the first examples in Catalonia (Sant Pere de Rodes, 1022) and developed around Camino de Santiago those of Aragon (Cathedral of Jaca, from 1054), Navarre (Leire, 1057), Castile (San Martin de Frómista, 1066) and Leon (San Isidoro -portico of 1067), ending in Galicia, where it raised the most outstanding work: the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (begun in 1075 with the plant of pilgrimage characteristic of most of the churches of the Way, from that of St. Sernin of Toulouse). The 12th century was the culmination of the style (Monastery of Ripoll, churches of Boí and Taüll -in Catalonia-, Castle of Loarre, Monastery of San Juan de la Peña -in Aragon, Palace of the Kings of Navarre (Estella), Done Mikel eliza (Estella-Lizarra), Saint Mary of Eunate, Saint Peter of Olite -in Navarre-, Segovian arcaded churches, Santo Domingo (Soria), San Juan de Duero -in Castile-, Cathedral of Zamora, Old Cathedral of Salamanca -in Leon-). From the late 12th is identified the transition from Romanesque to Gothic (Cathedral of Tarragona, La Seu Vella (Lleida)).[2]

Few, but notable are the churches of central plant, which are often associated with models of the Holy Land brought by the military orders (Eunate in Navarre, Vera Cruz in Segovia).[3]

Sculpture

The earliest works of the Romanesque sculpture in the Hispanic-Christian peninsular kingdoms are two beam of the Roussillon area Saint-Génis-des-Fontaines (dated in 1020)[4] and Sant Andreu de Sureda (which plays its forms). Also from the 11th century are the tympanum of the Cathedral of Jaca, the gables of San Isidoro (León), the Facade of Pratarías of Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (the Master Esteban), the cloister of Santo Domingo de Silos. In the 12th century emphasizes the facades of Santa Maria de Ripoll, of the Andre Maria erreginaren eliza (Zangoza/Sangüesa) of the San Pedro el Viejo (Huesca) and the cloister of Monastery of San Juan de la Peña. In the late 12th century belong the facades of the Church of Santa María del Camino (Carrión de los Condes) and Santo Domingo (Soria). In some works of this period is visible the transition to Gothic: the apostolate of the Cámara Santa (Oviedo), the facade of San Vicente (Ávila) and Portico of Glory of Cathedral of Santiago de Cosmpostela (of Master Mateo).[5] Another of the early sculptors of known name is Arnau Cadell (capitals of the cloister of Sant Cugat).

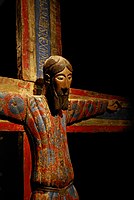

The carvings in the round bulge that have been preserved, in polychrome wood, usually have as theme the Christ crucified in the type called Majesty and the Madonna with Child in the type called sedes sapientiae ("Seat of Wisdom"). An exceptional sculpture complex is the Davallament of Sant Joan de les Abadesses, of transition to the Gothic.[6]

Painting

The Spanish Romanesque frescoes are outstanding: Pantheon of the Kings of San Isidoro (León) retained 'in situ', or the torn from its places of origin (San Baudelio de Berlanga, hermitage of la Vera Cruz (Maderuelo) -both in the Prado- and the collection assembled in the National Art Museum of Catalonia).[7]

The panel painting produced antependium that, especially in Catalonia collected the Italian-Byzantine influence from the 12th century (Altar frontal from La Seu d'Urgell or of The Apostles). In later period it evolves to the Gothic painting, of higher capacity narrative and lower stiffness (Altar frontal from Avià).[8]

-

Front of Seu d'Urgell or of the Apostle

-

Front Avià.

Sumptuary arts

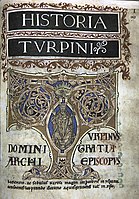

The preparation of manuscripts in the scriptorium of monasteries and cathedrals was an out-standing activity, continuing the Mozárabe tradition (Beatus) and incorporating the European influences (Libro de los testamentos, Tumbos compostelanos, Codex Calixtinus, etc.) have been retained some outstanding examples of tissues in liturgical vestments and tapestries (Tapestry of Creation of the Cathedral of Girona) The Ivory carving, of Andalusian influence, played an important workshop at the Leonese court. The goldsmith produced rich pieces (Cáliz de las Ágatas or of Doña Urraca -ca 1063-,[9] Ark of San Isidoro), including the incorporation of the technique of the Limoges enamels (Frontal of Santo Domingo de Silos).[10]

Areas

- Examples ordered geographically, from east to west

-

Frescos de Sant Climent de Taüll.

-

Tower and apses of Sant Climent de Taüll.

-

Portico of the church of Santa Maria de Ripoll.

-

Facade and towers of Ripoll.

-

Apses and dome of Ripoll.

-

Cloister of Ripoll.

-

Western Front of the Cathedral of Jaca.

-

Church-castle of Ujué.

-

Cloister of Santo Domingo de Silos.

-

The doubt of St. Thomas, in the cloister of Silos.

-

Central column of San Baudelio de Berlanga.

-

The Weddings at Cana, fresco of San Baudelio de Berlanga.

-

Tomb of the Holy Brothers Martyrs in the basilica of San Vicente (Ávila).

-

Santa María la Mayor of Arévalo (Romanesque-Mudéjar).

-

San Andrés de Cuéllar (Romanesque-Mudéjar).

-

Tower and atrium of San Esteban (Segovia).

-

Interior of the Church of la Vera Cruz (Segovia).

-

Corbels in the Collegiate of San Pedro de Cervatos.

-

Cloister of the Collegiate of Santa Juliana (Santillana del Mar).

-

Dome of the Old Cathedral (Salamanca).

-

San Román (Toledo) (Romanesque-Mudéjar).

-

San Lorenzo (Sahagún) (Romanesque-Mudéjar).

-

Royal Pantheon of San Isidoro (León).

-

Two of the apostles of the Cámara Santa (Oviedo).

-

Corbels in San Martino de Villallana. -Church of San Martino de Villallana-

-

Portico of the Cathedral of Ourense.

-

Vault, clerestory and arches of the central nave of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

-

Facade of Pratarías of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

-

Codex Calixtinus, 1140.

See also

References

- ^ Antonio Fernández, Emilio Barnechea and Juan Haro, History of Art, Barcelona: Vicens-Vives, 1992, ISBN 9788431625542, cp. 9, pg. 145-165.

- ^ Juan Haro, op. cit.

- ^ Raquel Gallego, Historia del Arte, Editex, 2009, pg. 188

- ^ Ficha en Artehistoria Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Juan Haro, op. cit.; Raquel Gallego, op. cit., pg. 189 y ss.

- ^ Raquel Gallego, op. cit, pg. 192.

- ^ Juan Haro, ``op. cit.

- ^ Raquel Gallego, op. cit., pg. 196

- ^ Virtual tour: THE GOBLET OF DOÑA URRACA, pious donation of the Queen of Zamora

- ^ Raquel Gallego, op. cit., pg. 197-198.