Kai Tak Airport

Kai Tak International Airport 啟德機場 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kai Tak Airport in 1998, the morning after its closure | |||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Public, Defunct | ||||||||||

| Operator | Civil Aviation Department | ||||||||||

| Location | Kowloon, Hong Kong | ||||||||||

| Opened | 1925 | ||||||||||

| Closed | 1998 | ||||||||||

| Hub for | Cathay Pacific, Dragonair, Hong Kong Airways, Cathay Pacific Cargo | ||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 9 m / 30 ft | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 22°19′43″N 114°11′39″E / 22.32861°N 114.19417°E | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Kai Tak Airport | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 啟德機場 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 启德机场 | ||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Káidāk Gēichèuhng | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Kai Tak International Airport (IATA: HKG, ICAO: VHHX) was the international airport of Hong Kong from 1925 until 1998. It was officially known as Hong Kong International Airport from 1954 to 6 July 1998, when it was closed and replaced by the new Hong Kong International Airport at Chek Lap Kok, 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the west.[1] It is often known as Hong Kong International Airport, Kai Tak,[2] or simply Kai Tak, to distinguish it from its successor which is often referred to as Chek Lap Kok Airport.

With numerous skyscrapers and mountains located to the north and its only runway jutting out into Victoria Harbour, landings at the airport were dramatic to experience and technically demanding for pilots.[3] The History Channel programme Most Extreme Airports ranked it as the 6th most dangerous airport in the world.[4]

The airport was home to Hong Kong's international carrier Cathay Pacific, as well as regional carrier Dragonair, freight airline Air Hong Kong and Hong Kong Airways. The airport was also home to the former RAF Kai Tak.

Geographic environment

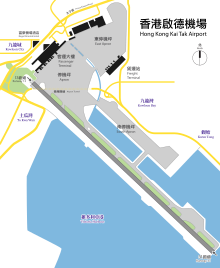

Kai Tak was located on the west side of Kowloon Bay in Kowloon, Hong Kong. The area is surrounded by rugged mountains. Less than 4 km (2.5 mi) to the north and northeast of the former runway 13 threshold is a range of hills reaching an elevation of 2,000 ft (610 m). To the east of the former 31 threshold, the hills are less than 3 km (1.9 mi) away. Immediately to the south of the airport is Victoria Harbour, and farther south is Hong Kong Island with hills up to 2,100 ft (640 m).

When Kai Tak closed, there was only one runway in use, numbered 13/31 and oriented southeast/northwest (134/314 degrees true, 136/316 degrees magnetic). The runway was made by reclaiming land from the harbour and was extended several times after its initial construction. The runway was 3,390 m (11,120 ft) long when the airport closed.

At the northern end of the runway, buildings rose up to six storeys just across a major multi-lane arterial road. The other three sides of the runway were surrounded by Victoria Harbour. The low-altitude turning manoeuvre before the shortened final approach was so spectacular that passengers could spot television sets in the apartments: "...as the plane banked sharply to the right for landing ... the people watching television in the nearby apartments seemed an unsettling arms length away."[5]

History

1920s to 1930s

The story of Kai Tak started in 1912 when two businessmen Ho Kai and Au Tak formed the Kai Tak Investment Company to reclaim land in Kowloon for development.[6] The land was acquired by the government for use as an airfield after the business plan failed.[7]

In 1924, Harry Abbott opened The Abbott School of Aviation on that piece of land.[8] Soon, it became a small grass strip runway airport for the RAF and several flying clubs which, over time, grew to include the Hong Kong Flying Club, the Far East Flying Training School, and the Aero Club of Hong Kong, which exist today as an amalgamation known as the Hong Kong Aviation Club. In 1928, a concrete slipway was built for seaplanes that used the adjoining Kowloon Bay.[1] The first control tower and hangar at Kai Tak were built in 1935. In 1936, the first domestic airline in Hong Kong was established.[citation needed]

World War II

Hong Kong fell into the hands of the Japanese in 1941 during World War II. In 1942, the Japanese army expanded Kai Tak, using many Allied prisoner-of-war (POW) labourers,[9] building two concrete runways, 13/31 and 07/25. Numerous POW diary entries exist recalling the gruelling work and long hours working on building Kai Tak.[10] During the process, the historic wall of the Kowloon Walled City and the 45-metre (148 ft) tall Sung Wong Toi, a memorial for the last Song dynasty emperor, were destroyed for materials.[11] A 2001 Environmental Study recommended that a new memorial be erected for the Sung Wong Toi rock and other remnants of the Kowloon area before Kai Tak.[12]

1945 to 1970s

From September 1945 to August 1946, the airport was a Royal Navy shore base, "HMS Nabcatcher",[13] the name previously attached to a Mobile Naval Air Base for the Fleet Air Arm. On 1 April 1947, a Royal Naval Air Station, HMS Flycatcher, was commissioned there.[14]

A plan to modify Kai Tak into a modern airport was released in 1954.[1] By 1957, runway 13/31 had been extended to 1,664 metres (5,459 ft), while runway 7/25 remained 1,450 metres (4,760 ft) long.[15] Bristol Britannia 102s took over BOAC's London-Tokyo flights in summer 1957 and were probably the largest airliners at the time to use the old airport. In 1958, the new NW/SE 2,550-metre (8,350 ft) long runway extending into Kowloon Bay was completed by land reclamation. The passenger terminal was completed in 1962.[1] The runway was extended in the mid-1970s to 3,390 metres (11,130 ft). This extension was completed in June 1974, but the full length of the runway was not put into use until 31 December 1975, as construction of the new Airport Tunnel had kept the northwestern end of the runway closed.[16]

In 1955 Kai Tak Airport featured in the film The Night My Number Came Up.

An Instrument Guidance System (IGS) was installed in 1974 to aid landing on runway 13. Use of the airport under adverse conditions was greatly increased.

Overcrowding in the 1980s and 1990s

The growth of Hong Kong also put a strain on the airport's capacity. Its usage was close to, and for some time exceeded, the designed capacity. The airport was designed to handle 24 million passengers per year, but in 1996, Kai Tak handled 29.5 million passengers, plus 1.56 million tonnes of freight, making it the third busiest airport in the world in terms of international passenger traffic, and busiest in terms of international cargo throughput.[1] Moreover, clearance requirements for aircraft takeoffs and landings made it necessary to limit the height of buildings that could be built in Kowloon. While Kai Tak was initially located far away from residential areas, the expansion of both residential areas and the airport resulted in Kai Tak being close to residential areas. This caused serious noise pollution for nearby residents and put height restrictions, which were removed after Kai Tak closed.[17] A night curfew from midnight to about 6:30 in the early morning also hindered operations.[18]

As a result, in the late 1980s, the Hong Kong Government began searching for alternative locations for a new airport in Hong Kong to replace the aging airport. After deliberating on a number of locations, including the south side of Hong Kong Island, the government decided to build the airport on the island of Chek Lap Kok off Lantau Island. A huge number of resources were mobilised to build this new airport, part of the ten programmes in Hong Kong's Airport Core Programme.

The Regal Meridien Hong Kong Airport Hotel, linked to the passenger terminal by a footbridge spanning Prince Edward Road, opened on 19 July 1982. This was Hong Kong's first airport hotel, and comprised 380 rooms including 47 suites.[19] As of 2018 the hotel still exists, but the footbridge has been demolished. It is one of the few remaining buildings related to Kai Tak Airport.

Closure and legacy of Kai Tak Airport

The new airport officially opened on 6 July 1998. All essential airport supplies and vehicles that were left in the old airport for operation (some of the non-essential ones had already been transported to the new airport) were transported to Chek Lap Kok in one early morning with a single massive move.

On 6 July 1998 at 01:28, after the last aircraft departed for Chek Lap Kok, Kai Tak was finally retired as an airport. The final flights were:

- The last arrival: Dragonair KA841 from Chongqing Jiangbei International Airport (Airbus A320) landed runway 13 at 23:38.

- The last scheduled commercial flight: Cathay Pacific CX251 to Heathrow Airport (Boeing 747-400) took off from runway 13 at 00:02.

- The last departure: Cathay Pacific CX3340 ferry flight to the new Hong Kong International Airport (Airbus A340-300) took off from runway 13 at 01:05.

A small ceremony celebrating the end of the airport was held inside the control tower after the last flight took off. Richard Siegel, then-director of civil aviation, gave a brief speech ending with the words "Goodbye Kai Tak, and thank you", before dimming the lights briefly and then turning them off.[20][21]

After the last plane, a Cathay Pacific A340-300, took off from Kai Tak International Airport to the new Hong Kong International Airport at 01:28 HKT, Kai Tak was closed, transferring its ICAO and IATA airport codes to the replacement airport at Chek Lap Kok.

Government reports later revealed that Chek Lap Kok airport was not completely ready to be opened to the public despite trial runs held. Water supply and sewers were not installed completely. Telephones were installed, but the lines were not connected. The baggage system did not undergo extensive troubleshooting and passenger baggage as well as cargo, much of which was perishable, were lost. The government decided to temporarily reactivate Kai Tak's cargo terminal to minimise the damage caused by a software bug in the new airport's cargo handling system. During this period, the airport was given temporary ICAO code VHHX.

The passenger terminal later housed government offices, automobile dealerships and showrooms, a go-kart racecourse, a bowling alley, a snooker hall, a golf range and other recreational facilities. Between December 2003 and January 2004, the passenger terminal was demolished. Many aviation enthusiasts were upset at the demise of Kai Tak because of the unique runway 13 approach. As private aviation was no longer allowed at Chek Lap Kok (having moved to Sek Kong Airfield), some enthusiasts had lobbied to keep about 1 km (0.62 mi) of the Kai Tak runway for general aviation, but the suggestion was rejected as the Government had planned to build a new cruise terminal at Kai Tak.[22]

The name Kai Tak is one of the names submitted by Hong Kong used in the lists of tropical cyclone names in the northwest Pacific Ocean and has been used four times as of 2017.

Former airlines and destinations

Passenger

Operations

Terminals and facilities

The Kai Tak airport consisted of a linear passenger terminal building with a car park attached at the rear. There were eight boarding gates attached to the terminal building.[29]

A freight terminal was located on the south side of the east apron and diagonally from the passenger terminal building.

Due to the limited space, the fuel tank farm was located between the passenger terminal and HAECO maintenance facilities (hangar).

Airlines based at Kai Tak

Several airlines were based at Kai Tak:

- Cathay Pacific, which operated a mixed Airbus, Boeing and some Lockheed all-widebody fleet of one hundred aircraft, providing scheduled services to the rest of Asia, Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East, Europe, South Africa and North America

- Dragonair

- Air Hong Kong Limited

- Hong Kong Airways

- British Airways

Other tenants included:

- Hong Kong Aviation Club

- Government Flying Service

- DFS Kai Tak Market

- Häagen Dazs

- Tin Tin Airport Restaurant

Runway 13 approach

The landing approach using runway 13 at Kai Tak was world-famous. To land on runway 13, an aircraft first took a descent heading northeast. The aircraft would pass over the crowded Victoria Harbour, and then the very densely populated areas of Western Kowloon. This leg of the approach was guided by an Instrument Guidance System, a modified Instrument landing system after 1974.[clarification needed]

Upon reaching a small hill above Kowloon Tsai Park marked with a large "aviation orange" and white checkerboard (22°20′06″N 114°11′04″E / 22.33500°N 114.18444°E), used as a visual reference point on the final approach (in addition to the middle marker on the Instrument Guidance System), the pilot needed to make a 47° visual right turn to line up with the runway and complete the final leg. The aircraft would be just 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) from touchdown, at a height of less than 1,000 feet (300 m) when the turn was made. Typically the plane would enter the final right turn at a height of about 650 feet (200 m) and exit it at a height of 140 feet (43 m) to line up with the runway. This demanding manoeuvre became known in the aviation community as the "Hong Kong Turn" or the "Checkerboard Turn". For many airline passengers on planes approaching and landing on Runway 13 at Kai Tak Airport, it became referred to as the "Kai Tak Heart Attack".[30]

Landing the runway 13 approach was already difficult with normal crosswinds since even if the wind direction was constant, it was changing relative to the aircraft during the 47° visual right turn. The landing would become even more challenging when crosswinds from the northeast were strong and gusty during typhoons. The mountain range northeast of the airport also makes wind vary greatly in both speed and direction. Watching large aircraft banking at low altitudes and taking big crab angles during their final approaches was popular for plane spotters. Despite the difficulty, the runway 13 approach was used most of the time due to the prevailing wind direction in Hong Kong.

Due to the turn in final approach, ILS was not available for runway 13 and landings had to follow a visual approach. This made the approach unusable in low visibility conditions.

Runway 13 departure

Runway 13 was the preferred departure runway for heavy aircraft due to the clear departure path, opposite that of the runway 31 departure. Heavy aircraft on departure using runway 13 would commonly be observed using nearly the entire length of the runway, particularly during summer days due to the air temperature.

Runway 31 approach

"Runway 31" meant the same physical runway as runway 13, but used in opposite direction. Landings on runway 31 were just like those on other normal runways where ILS landing was possible. Since the taxiway next to the runway would have been occupied by aircraft taxiing for takeoff, landing traffic could only exit the runway (to the right), at the very end. The path towards the runway passed within 300 metres to the north of Heng Fa Chuen on Hong Kong Island.

Runway 31 departure

When lined up for takeoff on runway 31, a range of hills including 1,500 feet (460 m) Beacon Hill would be right in front of the aircraft. The aircraft had to make a sharp 65-degree left turn soon after takeoff to avoid the hills (i.e. the reverse of a Runway 13 landing). If a runway change occurred due to wind change from runway 13 departures to runway 31 departures, planes that were loaded to maximum payload for runway 13 departures had to return to the terminal to offload some goods to provide enough climbing clearance over buildings during a runway 31 departure.

Private aviation

The Hong Kong Aviation Club formerly held most of its activities at Kai Tak but moved most of its aircraft to Shek Kong Airfield in 1994 after the hours for general aviation at Kai Tak were sharply reduced, to two hours per morning, as of July 1 that year.[31] The club ended its helicopter activities at Kai Tak on 9 July 2017.[32] The Kai Tak location, which it was able to use all days of the week, meant that helicopter training took less time compared to fixed-wing training, as usage at Shek Kong is restricted to weekends.[33]

Incidents and accidents

Many planes crashed at Kai Tak due to poor weather and hard approach

- On 25 January 1947, a Philippine Air Lines DC-3 aircraft crashed into Mount Parker, killing four crew members.[34][35]

- On 21 December 1948, a Civil Air Transport Douglas DC-4 struck Basalt Island after a descent through clouds. 33 were killed.[36]

- On 24 February 1949, a Cathay Pacific Douglas DC-3 crashed into a hillside near Braemar Reservoir after aborting an approach in poor visibility and attempting to go around. All 23 on board were killed.[37]

- On 11 March 1951, a Pacific Overseas Airlines Douglas DC-4 crashed after takeoff into the hills between Mount Butler and Mount Parker on Hong Kong Island. The captain of the aircraft allegedly failed to execute the turn left operation after departure. 23 were killed.[38]

- On 9 April 1951, a Siamese Airways Douglas DC-3 lost control on its turn while attempting a night-time visual approach. The captain allegedly allowed the aircraft to lose flying speed while attempting to turn quickly. 16 were killed.[39]

- On 19 April 1961, a US military Douglas DC-3 (C-47 Skytrain) bound for Formosa crashed into Mount Parker after takeoff. Of the 16 on board, 15 were killed.[40][35]

- On 24 August 1965, a United States Marine Corps C-130 Hercules crashed shortly after takeoff from runway 13, killing 59 of the 71 people on board. This was the deadliest accident at Kai Tak.[41]

- On 30 June 1967, a Thai Airways International Sud Aviation SE-210 Caravelle III crashed into Victoria Harbour while trying to land during a torrential rainstorm. A typhoon was some 150 miles (240 km) NW of Hong Kong, but the colony was not closed down in preparation of the typhoon. The co-pilot, who was flying the aircraft, unable to even see the runway due to the density of the rain, allegedly made an abrupt heading change, causing the aircraft to enter into a high rate of descent and crash into harbour waters to the right of the runway. The starboard wing snapped off on impact, and the aircraft rolled onto its starboard side, halving the number of escape routes. 24 were killed, but only 23 bodies were recovered at the scene. The final body was recovered after it was seen floating in the harbour six weeks later.[42]

- On 2 September 1977, a Transmeridian Air Cargo Canadair CL-44 lost control and crashed into the Tathong Channel on fire shortly after takeoff. The no. 4 engine was said to have failed, causing an internal fire in the engine and the aircraft fuel system that eventually resulted in a massive external fire. 4 were killed.[43][44]

- On 9 March 1978,[45] a China Airlines Boeing 737-200 was hijacked. The hijacker (the flight engineer of the flight) demanded to be taken to Mainland China (the airline was of the Republic of China on Taiwan, not the People's Republic of China, which controlled the mainland). The hijack lasted less than a day, and the hijacker was killed.[46]

- On 18 October 1983, a Lufthansa Boeing 747 freighter abandoned takeoff after engine no. 2 malfunctioned, probably at speed exceeding V1 (the takeoff/abort decision point). The aircraft overran the runway onto soft ground and sustained severe damage. 3 were injured.[47]

- On 31 August 1988, the right outboard flap of a CAAC Hawker Siddeley Trident operating Flight 301 hit approach lights of runway 31 while landing under rain and fog. The right main landing gear then struck a lip and collapsed, causing the aircraft to run off the runway and slip into the harbour. 7 were killed.[48]

- On 4 November 1993, a China Airlines Boeing 747-400, operating Flight 605, overran the runway while landing during a typhoon. The wind was gusting to gale force at the time. Despite the plane's unstable approach, the captain did not go around. It touched down more than 2/3 down the runway and was unable to stop before the runway ran out.[49] Although the aircraft ended up submerged beyond the end of the runway, there were only 23 minor injuries amongst the 396 passengers and crew.

- On 23 September 1994, a Heavylift Cargo Airlines Lockheed L-100-30 Hercules lost control shortly after takeoff from runway 13. The pitch control system of one of its propellers was said to have failed. 6 were killed.[50]

Redevelopment

2002 blueprint

In October 1998, the Government drafted a plan for the Kai Tak Airport site, involving the reclamation of 219 hectares (540 acres) of land. After receiving many objections, the Government scaled down the reclamation to 166 hectares (410 acres) in June 1999. The Territorial Development Department commenced a new study on the development of the area in November 1999, entitled "Feasibility Studies on the Revised Southeast Kowloon Development Plan", and a new public consultation exercise was conducted in May 2000, resulting in the land reclamation being further scaled down to 133 hectares (330 acres). The new plans based on the feasibility studies were passed by the chief executive in July 2002.[51] There were plans[when?] for the site of Kai Tak to be used for housing development, which was once projected to house around 240,000–340,000 residents. Due to calls from the public to protect the harbour and participate more deeply in future town planning, the scale and plan of the project were yet to be decided. There were also plans for a railway station and maintenance centre in the proposed plan for the Sha Tin to Central Link.

There were also proposals to dredge the runway to form several islands for housing, to build a terminal capable of accommodating cruise ships the size of the Queen Mary 2, and more recently, to house the Hong Kong Sports Institute, as well as several stadiums, in the case that the institute was forced to move so that the equestrian events of the 2008 Summer Olympics could be held at its present site in Sha Tin.

On 9 January 2004 the Court of Final Appeal ruled that no reclamation plan for Victoria Harbour could be introduced unless it passed an "overriding public interest" test.[52] Subsequently, the Government abandoned these plans.

Kai Tak Planning Review

The Government set up a "Kai Tak Planning Review" in July 2004 for further public consultation.[53] A number of plans were presented.

June 2006 blueprint

A new plan for the redevelopment of Kai Tak was issued by the government in June 2006. Under these proposals, hotels would be scattered throughout the 328-hectare (810-acre) site, and flats aimed at housing 86,000 new residents were proposed.

Other features of the plan included two cruise terminals and a large stadium.

October 2006 blueprint

The Planning Department unveiled a major reworking of its plans for the old Kai Tak airport site on 17 October 2006, containing "a basket of small measures designed to answer a bevy of concerns raised by the public".[54] The revised blueprint will also extend several "green corridors" from the main central park into the surrounding neighbourhoods of Kowloon City, Kowloon Bay and Ma Tau Kok.

The following features are proposed in the revised plan:

- two cruise terminals, with a third terminal to be added if the need arises

- a luxury hotel complex near the cruise terminals—the complex would sit about seven stories high, with hotel rooms atop commercial or tourist-related spaces

- an eight-station monorail linking the tourist hub with Kwun Tong

- a large stadium

- a "central park" to provide green space

- a 200-metre (660 ft) high public "viewing tower" near the tip of the runway

- a new bridge, likely to involve further reclamation of Victoria Harbour

The following are major changes:

- hotel spaces are to be centralised near the end of the runway, and will face into the harbour towards Central

- a third cruise terminal could be added at the foot of the hotel cluster if the need arises

- a second row of luxury residential spaces is to be added facing Kwun Tong, built on an elevated terrace or platform to preserve a view of the harbour

The government has promised that:

- the total amount of housing and hotel space will remain the same as proposed in June 2006

- plot ratios will be the same as before

- the total commercial space on the site will also remain about the same

The new bridge proposed by the government, joining the planned hotel district at the end of the runway with Kwun Tong, could be a potential source of controversy. Under the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance, no harbour reclamation can take place unless the Government can demonstrate to the courts an "overriding public need".[55]

The new Kai Tak blueprint was presented to the Legislative Council on 24 October 2006 after review by the Town Planning Board.

2011 onwards

In 2011, with most of the former Kai Tak area still abandoned, ideas were floated to develop the area for commercial property, citing shortages of office space and rising property costs.[56] In June 2013, the Kai Tak Cruise Terminal was opened on the tip of the former runway.[57][58] Two public housing estates opened on the northeast area of the site in 2013, providing over 13,000 new rental flats. As of 2018, the public estates have been joined by some private residential developments, now nearing completion.

Two new Mass Transit Railway (MTR) stations, Kai Tak and Sung Wong Toi, are scheduled to open in 2019 on the former airport lands.

See also

- Kai Tak Stadium

- List of buildings and structures in Hong Kong

- List of defunct international airports

- Lung Tsun Stone Bridge

References

- ^ a b c d e "Kai Tak Airport 1925–1998". Civil Aviation Department, Government of Hong Kong. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Photo of Kai Tak Airport, shown the official name of the airport Archived 18 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wong, Hiufu (12 June 2013). "Breathtaking photos of Hong Kong airport glory days". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Most Extreme Airports; The History Channel; 26 August 2010

- ^ Randy Harris (1999). The Year 2017: A Look at What's Coming in Asia. iUniverse. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-58348-137-0.

- ^ Kai Tak Airport History Archived 31 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Hong Kong ATC history, Munsang College history Archived 13 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Excerpt on Sir Kai Ho Kai". Blogthetalk.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hong Kong Aviation club Kai Tak History". Hkaviationclub.com.hk. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Work on Kai Tak Airport 11 September 1942 Newspaper Clipping Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harry Atkinson,Thomas Smith Forsyth,Bernard Castonguay,Garfield Loew,John McGee Former POWs also recount their attempts to sabotage construction, which included mixing large amounts of clay with the concrete for the runways.

- ^ "Hong Kong Tourist Association, "A MONUMENT RECORDING HISTORY: EMPEROR SUNG'S 'TERRACE'"". Discoverhongkong.com. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Kowloon Development Office" (PDF). Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Royal Navy Archive Archived 30 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kai Tak – Helicopter Database". Helis.com. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ The Aeroplane 2 August 1957

- ^ "Full runway in use today". South China Morning Post. 31 December 1975. p. 5.

- ^ "Aircraft Noise: Comparison Between Kai Tak and the new Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA)". Civil Aviation Department, Government of Hong Kong. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Official Record of Proceedings, Wednesday, 19 April 1995" (PDF). Hong Kong Legislative Council. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "HK's first airport hotel opens". South China Morning Post. 13 August 1982.

- ^ "Breathtaking photos of Hong Kong airport glory days". CNN. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ AP Archive (21 July 2015), Hong Kong - Kai Tak airport closes, retrieved 20 March 2017

- ^ "Kai Tak Planning Review – Report of Stage 2 Public Participation: Outline Zone Plans" (PDF). Planning Department, the Government of HKSAR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Airlines and Aircraft Serving Hong Kong Effective October 1, 1996". www.departedflights.com. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Airlines and Aircraft Serving Hong Kong Effective July 1, 1983". www.departedflights.com. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "BOAC timetable, 1948". Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "BOAC route map, 1971". Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Imperial Airways timetable, 1938". Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "大日本航空(1943)". tt-museum. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Sung Hin-lun: A Hundred Years of Aviation in Hong Kong. ISBN 962-04-2188-4

- ^ Steven K. Bailey (2009). Exploring Hong Kong: A Visitor's Guide to Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories. ThingsAsian Press. p. 136. ISBN 1934159166.

- ^ "Aviation club takes off for Sek Kong". scmp.com. South China Morning Post. 22 August 1994. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Hong Kong Aviation Club responds to media enquiries." Hong Kong Aviation Club. 27 May 2017. Retrieved on 18 April 2018. Chinese version.

- ^ "High-flyers have licence to thrill". South China Morning Post. 26 June 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

For anyone who has ever dreamt of flying, the first step to getting your wings is to join the Hong Kong Aviation Club (HKAC), the city's only flight training centre.[...]The Shek Kong Airfield is used by the People's Liberation Army during the week, with permission given to the club to use it during weekends.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "PAL tragedy: Manila officials here on investigations". South China Morning Post. 28 January 1947. p. 7.

- ^ a b "Survivor's condition "slightly improved"". South China Morning Post. 21 April 1961. p. 1.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas C-54B-5-DO N8342C Basalt Island". Aviation Safety. 21 December 1948. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas C-47A-90-DL VR-HDG North Point, Hong Kong". Aviation Safety. 24 February 1949. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Accident Database: Accident Synopsis 03111951". Airdisaster.com. 11 March 1951. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Accident Database: Accident Synopsis 04091951". Airdisaster.com. 9 April 1951. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Plane crashes Shaukiwan hill: Wreckage found after long and widespread search". South China Morning Post. 20 April 1961. p. 1.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed KC-130F Hercules 149802 Hong Kong-Kai Tak International Airport (HKG)". Aviation Safety. 24 August 1965. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Accident Database: Accident Synopsis 06301967". Airdisaster.com. 30 June 1967. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Four die as plane drops 'like a stone'". South China Morning Post. 3 September 1977. p. 1.

- ^ "Crash plane 'found'". South China Morning Post. 14 September 1977. p. 1.

- ^ https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1314&dat=19780310&id=zyFOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=4e0DAAAAIBAJ&pg=3048,3689614

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 737-281 B-1870 Hong Kong". Aviation Safety. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 747-230F D-ABYU Hong Kong-Kai Tak International Airport (HKG)". Aviation Safety. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident 2E B-2218 Hong Kong-Kai Tak International Airport (HKG)". Aviation Safety. 31 August 1988. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 747-409 B-165 Hong Kong-Kai Tak International Airport (HKG)". Aviation Safety. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed L-100-30 Hercules PK-PLV Hong Kong-Kai Tak International Airport (HKG)". Aviation Safety. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Planning history of Kai Tak Archived 21 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Judgement :Town Planning Board v Society for the Protection of the Harbour" (PDF). Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kai Tak planning review". Government of the Hong Kong SAR. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cheng, Jonathan (18 October 2006). "Kai Tak blueprint redrawn". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.harbourfront.org.hk/eng/content_page/protection.html?s=1

- ^ Kelvin Wong (1 October 2011). "Abandoned airport could solve office space dilemma". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Wong, Hiufu (14 June 2013). "Breathtaking photos of Hong Kong airport glory days". The Gateway. CNN. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Kai Tak Cruise Terminal". Retrieved 26 June 2013.