Gunshot wound

| Gunshot wound | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ballistic trauma, bullet wound |

| |

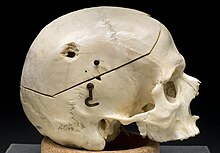

| Male skull showing bullet exit wound on parietal bone, 1950s. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Frequency | 1 million from interpersonal violence (2015)[1] |

| Deaths | 205,000 (2015)[2] |

A gunshot wound (GSW), also known as ballistic trauma, is a form of physical trauma sustained from the discharge of arms or munitions.[3] The most common forms of ballistic trauma stem from firearms used in armed conflicts, civilian sporting, recreational pursuits and criminal activity.[4] Damage is dependent on the firearm, bullet, velocity, entry point, and trajectory. Management can range from observation and local wound care to urgent surgical intervention.

Signs and symptoms

Trauma from a gunshot wound varies widely based on the bullet, velocity, entry point, trajectory, and effected anatomy. Gunshot wounds can be particularly devastating compared to other penetrating injuries because the trajectory and fragmentation of bullets can be unpredictable after entry. Additionally, gunshot wounds typically involve a large degree of nearby tissue disruption and destruction due to the physical effects of the projectile correlated with the bullet velocity classification.[5]

The immediate damaging effect of a gunshot wound is typically severe bleeding, and with it the potential for hypovolemic shock, a condition characterized by inadequate delivery of oxygen to vital organs. In the case of traumatic hypovolemic shock, this failure of adequate oxygen delivery is due to blood loss, as blood is the means of delivering oxygen to the body's constituent parts. Devastating effects can result when a bullet strikes a vital organ such as the heart, lungs or liver, or damages a component of the central nervous system such as the spinal cord or brain.

Common causes of death following gunshot injury include bleeding, hypoxia caused by pneumothorax, catastrophic injury to the heart and larger blood vessels, and damage to the brain or central nervous system. Non-fatal gunshot wounds frequently have severe and long-lasting effects, typically some form of major disfigurement and/or permanent disability.

Classification

Gunshot wounds are classified according to the speed of the projectile:

- Low-velocity: < 1,100 ft/s (340 m/s)

- Medium-velocity: 1,100 ft/s (340 m/s) to 2,000 ft/s (610 m/s)

- High-velocity: > 2,000 ft/s (610 m/s)

Bullets from handguns are generally less than 1,000 ft/s (300 m/s), while bullets from rifles exceed 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s). The US military commonly uses 5.56-mm bullets, which have a relatively low mass as compared with other bullets; however, the speed of these bullets is relatively fast. As a result, they produce a larger amount of kinetic energy, which is transmitted to the tissues of the target.[6] Muzzle velocity does not consider the effect of aerodynamic drag on the flight of the bullet for the sake of ease of comparison.

Physics

The degree of tissue disruption caused by a projectile is related to the cavitation the projectile creates as it passes through tissue. A bullet with sufficient energy will have a cavitation effect in addition to the penetrating track injury. As the bullet passes through the tissue, initially crushing then lacerating, the space left forms a cavity; this is called the permanent cavity. Higher-velocity bullets create a pressure wave that forces the tissues away, creating not only a permanent cavity the size of the caliber of the bullet but also a temporary cavity or secondary cavity, which is often many times larger than the bullet itself.[6] The extent of cavitation, in turn, is related to the following characteristics of the projectile:

- Kinetic energy: KE = 1/2mv2 (where m is mass and v is velocity). This helps to explain why wounds produced by missiles of higher mass and/or higher velocity produce greater tissue disruption than missiles of lower mass and velocity. The velocity of the bullet is a more important determinant of tissue injury. Although both mass and velocity contribute to the overall energy of the projectile, the energy is proportional to the mass while proportional to the square of its velocity. As a result, for a constant velocity, if the mass is doubled, the energy is doubled; however, if the velocity of the bullet is doubled, the energy increases four times. The initial velocity of a bullet is largely dependent on the firearm. The US military commonly uses 5.56-mm bullets, which have a relatively low mass as compared with other bullets; however, the speed of these bullets is relatively fast. As a result, they produce a larger amount of kinetic energy, which is transmitted to the tissues of the target.[6][7] The size of the temporary cavity is approximately proportional to the kinetic energy of the bullet and depends on the resistance of the tissue to stress.[8] Muzzle energy, which is based on muzzle velocity, is often used for sake of ease of comparison.

- Yaw Handgun bullets will generally travel in a relatively straight line or make one turn if a bone is hit. Upon travel through deeper tissue, high-energy rounds may become unstable as they decelerate, and may tumble (pitch and yaw) as the energy of the projectile is absorbed, causing stretching and tearing of the surrounding tissue.[6][9]

- Deformation Some bullets such as hollow-point bullets are designed to deform on impact, so as not to pass through the victim, and thus transfer all of their kinetic energy to tissue damage.[6]

- Fragmentation Most commonly, bullets do not fragment, and secondary damage from fragments of shattered bone is a more common complication than bullet fragments.[6]

Firearm

Handguns

Handguns are typically low velocity, and gunshot wounds from handguns are often similar to stabbings, that is, exhibiting permanent cavitation with little or no temporary cavitation.[6] "A handgun [wound] is simply a stabbing with a bullet," according to trauma surgeon Peter M. Rhee. "It goes in like a nail."[10] A gunshot wound from a handgun bullet might require only one surgery, according to Rhee.[11] Gunshot wounds from handguns are more common among civilians, and are usually less severe, than high-velocity wounds such as those caused by military or hunting weapons with a muzzle velocity of more than 600 meters per second.[12] Handgun bullets deposit insufficient kinetic energy in the tissue to cause temporary cavitation.[8]

Rifles

Military rifles are typically high velocity, as are AR-15 style rifles, the best-selling rifles in the United States.[13] Injuries from high-energy firearms and shotguns are associated with severe soft tissue damage.[12] Gunshot wounds from high-velocity rifles, such as military rifles and AR-15 style rifles, often exhibit temporary cavitation.[6][14][15] The muzzle velocity of a standard round from an AR-15 style rifle is about 980 m/s (3,200 ft/s).[6][13][11] With high-velocity rifle bullets, the temporary cavity is the most important mechanism of wound trauma.[16] With the high-velocity rounds of the AR-15 "it's as if you shot somebody with a Coke can," according to Rhee.[10] Radiologist Heather Sher described the cavitation caused by AR-15 style rifle gunshot wounds:

A typical AR-15 bullet leaves the barrel traveling almost three times faster than—and imparting more than three times the energy of—a typical 9mm bullet from a handgun...The bullet from an AR-15 passes through the body like a cigarette boat traveling at maximum speed through a tiny canal. The tissue next to the bullet is elastic—moving away from the bullet like waves of water displaced by the boat—and then returns and settles back. This process is called cavitation; it leaves the displaced tissue damaged or killed. The high-velocity bullet causes a swath of tissue damage that extends several inches from its path. It does not have to actually hit an artery to damage it and cause catastrophic bleeding. Exit wounds can be the size of an orange... If a victim takes a direct hit to the liver from an AR-15, the damage is far graver than that of a simple handgun-shot injury. Handgun injuries to the liver are generally survivable unless the bullet hits the main blood supply to the liver. An AR-15 bullet wound to the middle of the liver would cause so much bleeding that the patient would likely never make it to the trauma center to receive our care.[17][18][19]

A gunshot wound from an AR-15 style rifle is more lethal than a gunshot wound from a typical handgun.[11][14][17] A gunshot wound from an AR-15 bullet might require three to ten surgeries, according to Rhee.[11]

Civilian version of military rifles such as AR-15 style rifles "produce the same sort of horrific injuries seen on battlefields...You will see multiple organs shattered. The exit wounds can be a foot wide...Organs are damaged, blood vessels rip and many victims bleed to death before they reach a hospital,” according to trauma surgeons with both military and civilian experience interviewed by The New York Times in 2018.[20]

Gunshot wounds from high-velocity rifles have a lower rate of potentially survivable injuries as compared to other firearms, according to a 2016 retrospective study of 139 autopsy reports from 12 civilian public mass shootings in the United States. 371 gunshot wounds were found, included gunshot wounds from lower velocity handguns, multiple projectile shotguns, and high velocity rifles. Potentially survivable injuries were about equally distributed between handguns and shotguns; no gunshot wounds from high-velocity rifles were found to be potentially survivable. Compared and contrasted with the results of earlier studies of injuries in military combat, military combat injuries include injuries from explosives, military personnel wear body armor and ballistic protection helmets, while civilian public mass shooting events are closer range, have more injuries to the head and torso, and have a lower rate of potentially survivable injuries.[21]

Multiple gunshot wounds

Multiple gunshot wounds are more lethal than a single gunshot wound. The number of patients presenting with multiple gunshot wounds, and the likelihood of dying from gunshot wounds, are increasing, according to a 2016 analysis of trauma admissions at the Denver Health Medical Center reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Some firearms have features or accessories that facilitate delivering multiple "rounds on target," such as high-capacity magazines and recoil buffers.[6][14][22][23]

Management

Workup

Initial workup for a gunshot wound is approached in the same way as any acute trauma case. A rapid first pass of the person is conducted using advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol in order to ensure that the most vital functions are intact.[24] These include:

- A) Airway - Assess and protect airway and cervical spine

- B) Breathing - Maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation

- C) Circulation - Assess for and control bleeding to maintain organ perfusion including focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST)

- D) Disability - Perform basic neurological exam including Glascow Coma Scale (GCS)

- E) Exposure - Expose entire body and search for any missed injuries, entry points, and exit points while maintaining body temperature

Depending on the extent of injury, management can range from urgent surgical intervention to observation. As such, any history from the scene such as gun type, shots fired, shot direction and distance, blood loss on scene, and pre-hospital vitals signs can be very helpful in directing management. Unstable people with signs of bleeding that cannot be controlled during the initial evaluation require immediate surgical exploration in the operating room.[24] Otherwise, management protocols are generally dictated by anatomic entry point and anticipated trajectory.

Neck

A gunshot wound to the neck can be particularly dangerous because of the high number of vital anatomical structures contained within a small space. The neck contains the larynx, trachea, pharynx, esophagus, vasculature (carotid, subclavian, and vertebral arteries; jugular, brachiocephalic, and vertebral veins; thyroid vessels), and nervous system anatomy (spinal cord, cranial nerves, peripheral nerves, sympathetic chain, brachial plexus). Gunshots to the neck can thus cause severe bleeding, airway compromise, and nervous system injury.[25]

Initial assessment of a gunshot wound to the neck involves non-probing inspection of whether the injury is a penetrating neck injury (PNI), classified by violation of the platsyma muscle.[25] If the platsyma is intact, the wound is considered superficial and only requires local wound care. If the injury is a PNI, surgery should be consulted immediately while the case is being managed. Of note, wounds should not be explored on the field or in the emergency department given the risk of exacerbating the wound.

Due to the advances in diagnostic imaging, management of PNI has been shifting from a "zone-based" approach, which uses anatomical site of injury to guide decisions, to a "no-zone" approach which uses a symptom-based algorithm.[26] The no-zone approach uses a hard signs and imaging system to guide next steps. Hard signs include airway compromise, unresponsive shock, diminished pulses, uncontrolled bleeding, expanding hematoma, bruits/thrill, air bubbling from wound or extensive subcutaneous air, stridor/hoarseness, neurological deficits.[26] If any hard signs are present, immediate surgical exploration and repair is pursued alongside airway and bleeding control. If there are no hard signs, the person receives a multi-detector CT angiography for better diagnosis. A directed angiography or endoscopy may be warranted in a high-risk trajectory for the gunshot. A positive finding on CT leads to operative exploration. If negative, the person may be observed with local wound care.[26]

Chest

Important anatomy in the chest includes the chest wall, ribs, spine, spinal cord, intercostal neurovascular bundles, lungs, bronchi, heart, aorta, major vessels, esophagus, thoracic duct, and diaphragm. Gunshots to the chest can thus cause severe bleeding (hemothorax), respiratory compromise (pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion, tracheobronchial injury), cardiac injury (pericardial tamponade), esophageal injury, and nervous system injury.[27]

Initial workup as outlined in the Workup section is particularly important with gunshot wounds to the chest because of the high risk for direct injury to the lungs, heart, and major vessels. Important notes for the initial workup specific for chest injuries are as follows. In people with pericardial tamponade or tension pneumothorax, the chest should be evacuated or decompressed if possible prior to attempting tracheal intubation because the positive pressure ventilation can cause hypotention or cardiovascular collapse.[28] Those with signs of a tension pneumothorax (asymmetric breathing, unstable blood flow, respiratory distress) should immediately receive a chest tube (> French 36) or needle decompression if chest tube placement is delayed.[28] FAST exam should include extended views into the chest to evaluate for hemopericardium, pneumothorax, hemothorax, and peritoneal fluid.[28]

Those with cardiac tamponade, uncontrolled bleeding, or a persistent air leak from a chest tube all require surgery.[29] Cardiac tamponade can be identified on FAST exam. Blood loss warranting surgery is 1-1.5 L of immediate chest tube drainage or ongoing bleeding of 200-300 mL/hr.[29][30] Persistent air leak is suggestive of tracheobronchial injury which will not heal without surgical intervention.[29] Depending on the severity of the person's condition and if cardiac arrest is recent or imminent, the person may require surgical intervention in the emergency department, otherwise known as an emergency department thoracotomy (EDT).[31]

However, not all gunshot to the chest require surgery. Asymptomatic people with a normal chest X-ray can be observed with a repeat exam and imaging after 6 hours to ensure no delayed development of pneumothorax or hemothorax.[28] If a person only has a pneumothorax or hemothorax, a chest tube is usually sufficient for management unless there is large volume bleeding or persistent air leak as noted above.[28] Additional imaging after initial chest X-ray and ultrasound can be useful in guiding next steps for stable people. Common imaging modalities include chest CT, formal echocardiography, angiography, esophagoscopy, esophagography, and bronchoscopy depending on the signs and symptoms.[32]

Abdomen

Important anatomy in the abdomen includes the stomach, small bowel, colon, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, spine, diaphragm, descending aorta, and other abdominal vessels and nerves. Gunshots to the abdomen can thus cause severe bleeding, release of bowel contents, peritonitis, organ rupture, respiratory compromise, and neurological deficits.

The most important initial evaluation of a gunshot wound to the abdomen is whether there is uncontrolled bleeding, inflammation of the peritoneum, or spillage of bowel contents. If any of these are present, the person should be transferred immediately to the operating room for laparotomy.[33] If it is difficult to evaluate for those indications because the person is unresponsive or incomprehensible, it is up to the surgeon's discretion whether to pursue laparotomy, exploratory laparoscopy, or alternative investigative tools.

Although all people with abdominal gunshot wounds were taken to the operating room in the past, practice has shifted in recent years with the advances in imaging to non-operative approaches in more stable people.[34] If the person's vital signs are stable without indication for immediate surgery, imaging is done to determine the extent of injury.[34] Ultrasound (FAST) and help identify intra-abdominal bleeding and X-rays can help determine bullet trajectory and fragmentation.[34] However, the best and preferred mode of imaging is high-resolution multi-detector CT (MDCT) with IV, oral, and sometimes rectal contrast.[34] Severity of injury found on imaging will determine whether the surgeon takes an operative or close observational approach.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has become largely obsolete with the advances in MDCT, with use limited to centers without access to CT to guide requirement for urgent transfer for operation.[34]

Extremities

The four main components of extremities are bones, vessels, nerves, and soft tissues. Gunshot wounds can thus cause severe bleeding, fractures, nerve deficits, and soft tissue damage. The Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS) is used to classify the severity of injury and evaluates for severity of skeletal and/or soft tissue injury, limb ischemia, shock, and age.[35] Depending on the extent of injury, management can range from superficial wound care to limb amputation.

Vital sign stability and vascular assessment are the most important determinants of management in extremity injuries. As with other traumatic cases, those with uncontrolled bleeding require immediate surgical intervention.[24] If surgical intervention is not readily available and direct pressure is insufficient to control bleeding, tourniquets or direct clamping of visible vessels may be used temporarily to slow active bleeding.[36] People with hard signs of vascular injury also require immediate surgical intervention. Hard signs include active bleeding, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, bruit/thrill, absent distal pulses and signs of extremity ischemia.[37]

For stable people without hard signs of vascular injury, an injured extremity index (IEI) should be calculated by comparing the blood pressure in the injured limb compared to an uninjured limb in order to further evaluate for potential vascular injury.[38] If the IEI or clinical signs are suggestive of vascular injury, the person may undergo surgery or receive further imaging including CT angiography or conventional arteriography.

In addition to vascular management, people must be evaluated for bone, soft tissue, and nerve injury. Plain films can be used for fractures alongside CTs for soft tissue assessment. Fractures must be debrided and stabilized, nerves repaired when possible, and soft tissue debrided and covered.[39] This process can often require multiple procedures over time depending on the severity of injury.

Epidemiology

Assault by firearm resulted in 173,000 deaths globally in 2015, up from 128,000 deaths in 1990.[2][40] Additionally, there were 32,000 unintentional firearm deaths in 2015.[2] As of 2016, the countries with the highest rates of gun violence per capita were El Salvador, Venezuela, and Guatemala with 40.3, 34.8, and 26.8 violent gun deaths per 100,000 people respectively.[41] The countries with the lowest rates of were Singapore, Japan, and South Korea with 0.03, 0.04, and 0.05 violent gun deaths per 100,000 people respectively.[41]

United States

The United States has the 31st highest rate of violent gun deaths in the world with 3.85 deaths per 100,000 people in 2016.[41] The majority of all homicides and suicides are firearm-related, and the majority of firearm-related deaths are the result of murder and suicide.[42] When sorted by GDP, however, the United States has a much higher violent gun death rate compared to other developed countries, with over 10 times the number of firearms assault deaths than the next four highest GDP countries combined.[43] Gunshot violence is the third most costly etiology of injury and the fourth most expensive form of hospitalization in the United States.[12]

History

Hieronymus Brunschwig argued that infection of gunshot wounds was a result of poisoning by gunpowder, which provided the rationale for cauterizing wounds. Ambroise Paré wrote in his 1545 book, The Method of Curing Wounds Caused by Arquebus and Firearms, that wounds should be sealed rather than cauterized.[44][45] John Hunter argued that infection was not caused by poisoning.

Until the 1880s, the standard practice for treating a gunshot wound called for physicians to insert their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe and locate the path of the bullet.[46] Surgically opening abdominal cavities to repair gunshot wounds,[47] germ theory, and Joseph Lister's technique for antiseptic surgery using diluted carbolic acid, first demonstrated in 1865, had not yet been accepted as standard practice. For example, sixteen doctors attended to President James A. Garfield after he was shot, and most probed the wound with their fingers or dirty instruments.[48] Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in Garfield's death.[46][49]

At almost the same time, in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, on 13 July 1881, George E. Goodfellow performed the first laparotomy to treat an abdominal gunshot wound.[50]: M-9 Goodfellow pioneered the use of sterile techniques in treating gunshot wounds,[51] washing the person's wound and his hands with lye soap or whisky.[52] He became America's leading authority on gunshot wounds[53] and is credited as the United States' first civilian trauma surgeon.[54]

Wilhelm Röntgen's discovery of X-rays in 1895 led to the use of radiographs to locate bullets in wounded soldiers.[44]

Survival rates for gunshot wounds improved among US military personnel during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, due in part to helicopter evacuation, along with improvements in resuscitation and battlefield medicine.[44][55] Similar improvements were seen in US trauma practices during the Iraq War.[56] Some military trauma care practices are disseminated by citizen soldiers who return to civilian practice.[44][57][58] One such practice is to transfer major trauma cases to an operating theater as soon as possible, to stop internal bleeding. Within the United States, the survival rate for gunshot wounds has increased, leading to apparent declines in the gun death rate in states that have stable rates of gunshot hospitalizations.[59][60][61][62]

Research

Research into gunshot wounds is hampered by lack of funding. Federal-funded research into firearm injury, epidemiology, violence, and prevention is minimal. Pressure from the National Rifle Association, the gun lobby, and some gun owners, expressing concerns regarding increased government controls on freedom and guns, is highly effective in preventing related research.[6]

See also

- Battlefield medicine

- Blast injury

- Hydrostatic shock

- Multiple gunshot suicide

- Penetrating trauma

- Stab wound

- Stopping power

References

- ^ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Wang, Haidong; Naghavi, MohsenA (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1.

- ^ Mahoney, P. F., et al. (2004). Section 1 : Introduction, Background and Science p4

- ^ Mahoney, P. F., et al. (2004). The International Small Arms Situation p6

- ^ Lamb, C. M.; Garner, J. P. (April 2014). "Selective non-operative management of civilian gunshot wounds to the abdomen: a systematic review of the evidence". Injury. 45 (4): 659–666. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.07.008. ISSN 1879-0267. PMID 23895795.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rhee, Peter M.; Moore, Ernest E.; Joseph, Bellal; Tang, Andrew; Pandit, Viraj; Vercruysse, Gary (1 June 2016). "Gunshot wounds: A review of ballistics, bullets, weapons, and myths". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 80 (6): 853–867. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001037. ISSN 2163-0755. PMID 26982703.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hanna, Tarek N.; Shuaib, Waqas; Han, Tatiana; Mehta, Ajeet; Khosa, Faisal (1 July 2015). "Firearms, bullets, and wound ballistics: An imaging primer". Injury. 46 (7). Elsevier: 1186–1196. PMID 25724396.

Each bullet has its intrinsic mass, but the initial velocity is largely a function of the firearm. Due to short barrel length, handguns produce a low-velocity projectile that usually deposits all of its kinetic energy within the target, thus creating an entry but no exit wound. Rifles have longer barrel lengths that produce a high velocity, high-energy projectile.

- ^ a b Maiden, Nicholas (September 2009). "Ballistics reviews: mechanisms of bullet wound trauma". Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 5 (3): 204–209. PMID 19644779.

...the temporary cavity is the most important factor in wound ballistics of high velocity rifle bullets...the importance of the temporary cavity is recognized by all other contemporary researchers...The temporary cavity also has little or no wounding potential with handgun bullets because the amount of kinetic energy deposited in the tissue is insufficient to cause remote injuries. The size of the temporary cavity is approximately proportional to the kinetic energy of the striking bullet and also the amount of resistance the tissue has to stress.

- ^ Kolata, Gina; Chivers, C. J. (4 March 2018). "Wounds From Military-Style Rifles? 'A Ghastly Thing to See'". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

Many factors determine the severity of a wound, including a bullet's mass, velocity and composition, and where it strikes. The AR-15, like the M4 and M16 rifles issued to American soldiers, shoots lightweight, high-speed bullets that can cause grievous bone and soft tissue wounds, in part by turning sideways, or "yawing," when they hit a person. Surgeons say the weapons produce the same sort of horrific injuries seen on battlefields. Civilian owners of military-style weapons can also buy soft-nosed or hollow-point ammunition, often used for hunting, that lacks a full metal jacket and can expand and fragment on impact. Such bullets, which can cause wider wound channels, are proscribed in most military use. A radiologist at the hospital that treated victims of the Parkland attack wrote in The Atlantic about a surgeon there who "opened a young victim in the operating room and found only shreds of the organ that had been hit."

- ^ a b Dickinson, Tim (22 February 2018). "All-American Killer: How the AR-15 Became Mass Shooters' Weapon of Choice". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Zhang, Sarah (17 June 2016). "What an AR-15 Can Do to the Human Body". Wired. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

The AR-15 is America's most popular rifle...These high-velocity bullets can damage flesh inches away from their path, either because they fragment or because they cause something called cavitation. When you trail your fingers through water, the water ripples and curls. When a high-velocity bullet pierces the body, human tissues ripples as well—but much more violently. The bullet from an AR-15 might miss the femoral artery in the leg, but cavitation may burst the artery anyway, causing death by blood loss. A swath of stretched and torn tissue around the wound may die.

- ^ a b c Lichte, Philipp; Oberbeck, Reiner; Binnebösel, Marcel; Wildenauer, Rene; Pape, Hans-Christoph; Kobbe, Philipp (17 June 2010). "A civilian perspective on ballistic trauma and gunshot injuries". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 18 (35). PMC 2898680. PMID 20565804.

Low-velocity wounds are attributed to projectiles with muzzle velocity of less than 600 meter per second (m/s), are classically caused by handguns and are therefore more common in the civilian population. The injury is usually less severe as compared with high-velocity wounds, which are caused by military or hunting weapons with a muzzle velocity of more than 600 meter per second...Low-energy injuries are usually associated with minimal soft tissue damage and low risk of wound infection...In contrast, high-energy and shotgun injuries are associated with severe soft tissue damage and require an aggressive debridement with several second-look surgeries.

- ^ a b Wing, Nick; Reilly, Mollie (14 February 2018). "Here's What You Need To Know About The Weapons Of War Used In Mass Shootings". HuffPost. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

The specifications of assault-style rifles vary depending on ammunition, but many tests put the muzzle velocity of a standard round from an AR-15 at 3,200 feet per second, making it accurate up to 500 yards ― more than a quarter-mile. This makes rounds from an AR-15 or other assault-style weapons far more devastating than those fired from small-caliber handguns.

- ^ a b c Moore, Ernest E. (15 February 2018). "The Parkland shooter's AR-15 was designed to kill as efficiently as possible". NBC News. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

...the standard AR-15 bullet travels at 3,251 feet per second and delivers 1300 foot pounds. Tissue destruction of the AR-15 is further enhanced by cavitation, which is the destruction of tissue beyond the direct pathway of the bullet...

- ^ Santhanam, Laura; Marder, Jenny (17 February 2018). "What a bullet does to a human body". PBS NewsHour. PBS. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

There is a tremendous difference in the amount of energy associated with a bullet from an AR-15 rifle and that of a handgun, he said. Nikolas Cruz, the shooting suspect who opened fire on Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, killing 17 people, used an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, according to local police. If a bullet from a handgun strikes a liver, it injures the organ by poking a hole and causing tissue disruption around the path of the bullet. More specifically, a 9-millimeter handgun creates a hole that disrupts three quarters of an inch around the bullet's path, Smock said. "But with a rifle round, you have massive tissue disruption," Smock said. "Rather than three quarters of an inch around the wound path, it is disrupted three to four inches around that same tissue."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

maiden2009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Sher, Heather (22 February 2018). "What I Saw Treating the Victims From Parkland Should Change the Debate on Guns". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Daugherty, Alex (24 February 2018). "Mangled tissue and softball-sized exit wounds: Why AR-15 injuries are so devastating". Miami Herald. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

The AR-15, the semiautomatic rifle used at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history, uses bullets that can cause softball-sized exit wounds, leaving behind a significantly larger trail of mangled tissue compared to handgun bullets. For trauma surgeons, the injuries are harder to repair. For victims, the chances of survival are lower...The AR-15 and similar rifles fire bullets at a speed of about 2,800 to 3,000 feet per second, compared to a 9 millimeter handgun, which fires bullets at a speed of between 700 and 1,100 feet per second, according to Dr. David Shatz, a trauma surgeon at the University of California, Davis...Shatz said bullets cause permanent cavities, where tissue is destroyed, and temporary cavities, which are areas around the permanent cavity that open up for a fraction of a second because of the "sonic force" of a bullet. Cavities caused by bullets like the .223 caliber bullet typically fired by the AR-15 are much larger than the cavities caused by handgun bullets.

- ^ Pasha-Robinson, Lucy (23 February 2018). "Florida shooting: Doctor describes 'sledgehammer' injuries inflicted by AR-15". The Independent. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Kolata, Gina; Chivers, C. J. (4 March 2018). "Wounds from Military-Style Rifles? 'A Ghastly Thing to See". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Smith, Edward Reed; Shapiro, Geoff; Sarani, Babak (July 2016). "The profile of wounding in civilian public mass shooting fatalities". Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 81 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001031. ISSN 2163-0755. PMID 26958801.

- ^ Christensen, Jen (14 June 2016). "Gunshot wounds deadlier than ever as guns get increasingly powerful". CNN. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Sauaia, Angela; Gonzalez, Eduardo; Moore, Hunter B.; Bol, Kirk; Moore, Eugene E. (2016). "Fatality and Severity of Firearm Injuries in a Denver Trauma Center, 2000-2013". Journal of the American Medical Association. 315 (22): 2465–2467. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5978.

- ^ a b c Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Student Course Manual (9th Edition). American College of Surgeons. 2012. ISBN 1880696029.

- ^ a b Tisherman, Samuel A.; Bokhari, Faran; Collier, Bryan; Cumming, John; Ebert, James; Holevar, Michele; Kurek, Stanley; Leon, Stuart; Rhee, Peter (1 May 2008). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Penetrating Zone II Neck Trauma". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 64 (5): 1392–1405. doi:10.1097/ta.0b013e3181692116. ISSN 0022-5282.

- ^ a b c Shiroff, Adam M.; Gale, Stephen C.; Martin, Niels D.; Marchalik, Daniel; Petrov, Dmitriy; Ahmed, Hesham M.; Rotondo, Michael F.; Gracias, Vicente H. (January 2013). "Penetrating neck trauma: a review of management strategies and discussion of the 'No Zone' approach". The American Surgeon. 79 (1): 23–29. ISSN 1555-9823. PMID 23317595.

- ^ Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice. Marx, John A.,, Hockberger, Robert S.,, Walls, Ron M.,, Biros, Michelle H.,, Danzl, Daniel F.,, Gausche-Hill, Marianne, (Eighth edition ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455749874. OCLC 853286850.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e Karmy-Jones, Riyad; Namias, Nicholas; Coimbra, Raul; Moore, Ernest E.; Schreiber, Martin; McIntyre, Robert; Croce, Martin; Livingston, David H.; Sperry, Jason L. (December 2014). "Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: penetrating chest trauma". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 77 (6): 994–1002. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000000426. ISSN 2163-0763. PMID 25423543.

- ^ a b c Meredith, J. Wayne; Hoth, J. Jason (February 2007). "Thoracic trauma: when and how to intervene". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 87 (1): 95–118, vii. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2006.09.014. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 17127125.

- ^ Karmy-Jones, Riyad; Jurkovich, Gregory J. (March 2004). "Blunt chest trauma". Current Problems in Surgery. 41 (3): 211–380. doi:10.1016/j.cpsurg.2003.12.004. PMID 15097979.

- ^ Burlew, Clay Cothren; Moore, Ernest E.; Moore, Frederick A.; Coimbra, Raul; McIntyre, Robert C.; Davis, James W.; Sperry, Jason; Biffl, Walter L. (December 2012). "Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: resuscitative thoracotomy". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 73 (6): 1359–1363. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318270d2df. ISSN 2163-0763. PMID 23188227.

- ^ Mirvis, Stuart E. (April 2004). "Diagnostic imaging of acute thoracic injury". Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 25 (2): 156–179. PMID 15160796.

- ^ Jansen, Jan O.; Inaba, Kenji; Resnick, Shelby; Fraga, Gustavo P.; Starling, Sizenando V.; Rizoli, Sandro B.; Boffard, Kenneth D.; Demetriades, Demetrios (May 2013). "Selective non-operative management of abdominal gunshot wounds: survey of practise". Injury. 44 (5): 639–644. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2012.01.023. PMID 22341771.

- ^ a b c d e Pryor, John P.; Reilly, Patrick M.; Dabrowski, G. Paul; Grossman, Michael D.; Schwab, C. William (March 2004). "Nonoperative management of abdominal gunshot wounds". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 43 (3): 344–353. doi:10.1016/S0196064403008151. PMID 14985662.

- ^ Johansen, K.; Daines, M.; Howey, T.; Helfet, D.; Hansen, S. T. (May 1990). "Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma". The Journal of Trauma. 30 (5): 568–572, discussion 572–573. PMID 2342140.

- ^ Fox, Nicole; Rajani, Ravi R.; Bokhari, Faran; Chiu, William C.; Kerwin, Andrew; Seamon, Mark J.; Skarupa, David; Frykberg, Eric; Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (November 2012). "Evaluation and management of penetrating lower extremity arterial trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 73 (5 Suppl 4): S315–320. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31827018e4. PMID 23114487.

- ^ "National Trauma Data Bank 2012 Annual Report". American College of Surgeons 8.

- ^ "WESTERN TRAUMA ASSOCIATION". westerntrauma.org. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Management of Complex Extremity Trauma". American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub". vizhub.healthdata.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Wellford, Charles F.; Pepper, John V.; Petrie, Carol V. (2005). Firearms and violence: A critical review (Report). National Research Council.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Marczak, Laurie; O’Rourke, Kevin; Shepard, Dawn; Leach-Kemon, Katherine; Evaluation, for the Institute for Health Metrics and (13 December 2016). "Firearm Deaths in the United States and Globally, 1990-2015". JAMA. 316 (22). doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16676. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ a b c d Manring MM, Hawk A, Calhoun JH, Andersen RC (2009). "Treatment of war wounds: a historical review". Clin Orthop Relat Res. 467 (8): 2168–91. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0738-5. PMC 2706344. PMID 19219516.

- ^ Pruitt, Basil A. (2006). "Combat Casualty Care and Surgical Progress". Annals of Surgery. 243 (6): 715–729. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000220038.66466.b5. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1570575. PMID 16772775.

- ^ a b Schaffer, Amanda (25 July 2006). "A president felled by an assassin and 1880's medical care". New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Crane, Michael A. (2003). "Dr. Goodfellow: gunfighter's surgeon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The death of President Garfield, 1881". Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ Rutkow, Ira (2006). James A. Garfield. New York: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8050-6950-1. OCLC 255885600.

- ^ Charles E. Sajous, ed. (1890). Annual of the Universal Medical Sciences And Analytical Index 1888-1896. Vol. 3. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

- ^ "Come face to face with history" (PDF). Cochise County. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Edwards, Josh (2 May 1980). "George Goodfellow's medical treatment of stomach wounds became legendary". The Prescott Courier. pp. 3–5.

- ^ "Dr. George Goodfellow". Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tombstone's doctor famous as surgeon". The Prescott Courier. 12 September 1975. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Chapter 3 - Medical Support 1965-1970".[dead link]

- ^ Service, Lee Bowman, Scripps Howard News (16 March 2013). "Iraq War 10 year anniversary: Survival rate of wounded soldiers better than previous wars".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Military medical techniques saving lives at home - News stories - GOV.UK".

- ^ "The role of the gun in the advancement of medicine". 8 January 2015.

- ^ Jena, Anupam B.; Sun, Eric C.; Prasad, Vinay (2014). "Does the Declining Lethality of Gunshot Injuries Mask a Rising Epidemic of Gun Violence in the United States?". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 29 (7): 1065–1069. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2779-z. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 4061370. PMID 24452421.

- ^ "Lower murder rate linked to medical advance, not less violence".

- ^ Fields, Gary; McWhirter, Cameron (8 December 2012). "In Medical Triumph, Homicides Fall Despite Soaring Gun Violence" – via Wall Street Journal.

- ^ http://www.universitychurchchicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Murder-and-Medicine.pdf

Bibliography

- Mahoney, P. F., Ryan, J., Brooks, A. J., Schwab, C. W. (2004) Ballistic Trauma – A practical guide 2nd ed. Springer:Leonard Cheshire

- Krug E. E., ed. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Small arms and global health. Paper prepared for SALW talks. Geneva: July 2001.