Denver International Airport

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

Denver International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:Denver International Airport Logo.png | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City & County of Denver Department of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | City & County of Denver Department of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Denver, the Front Range Urban Corridor, Eastern Colorado, Southeastern Wyoming, and the Nebraska Panhandle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Northeastern Denver, Colorado, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | Passenger Airlines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 5,431 ft / 1,655 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°51′42″N 104°40′23″W / 39.86167°N 104.67306°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | http://www.flydenver.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

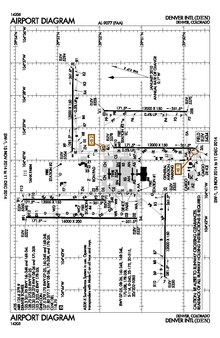

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2017) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Denver International Airport[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Denver International Airport (IATA: DEN, ICAO: KDEN, FAA LID: DEN), also commonly known as DIA, is an international airport in Denver, Colorado, United States. At 33,531 acres (13,570 ha, 52.4 sq mi),[4] it is the largest airport in the United States by total land area.[5] Runway 16R/34L, with a length of 16,000 feet (4,877 m), is the longest public use runway in the United States.

As of 2017, DEN was the 20th busiest airport in the world and the fifth busiest in the United States by passenger traffic handling 61,379,396 passengers. It also has the third largest domestic connection network in the country.

DEN has non-stop service to destinations throughout North America, Latin America, Europe, and Asia serving over 195 destinations in 2018. The airport is in northeastern Denver and is owned and operated by the City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. DEN was voted as the "Best Airport in North America" by readers of Business Traveler Magazine for six years in a row (2005–2010)[6] and was named "America's Best Run Airport" by Time Magazine in 2002.[7]

As of 2018, Denver International Airport has been rated by Skytrax as the 29th "Best Airport in the World," ranking #1 in the United States. Skytrax also named DIA as the second "Best Regional Airport in North America" for 2017, and the fourth "Best Regional Airport in the World."

The airport is the main hub for Frontier Airlines. It is also the fourth-largest hub for United Airlines with 375 daily departures to 141 destinations. The airport is Southwest Airlines' fourth most utilized airport and fastest-growing market, with 190 daily departures to nearly 60 destinations.

DEN is the only airport in the United States to have implemented an ISO 14001-certified environmental management system covering the entire airport.[8]

The airport is accessible via Peña Boulevard as well as the A Line commuter rail from Denver Union Station.

Features

Aesthetics

The Jeppesen Terminal's internationally recognized peaked roof, designed by Fentress Bradburn Architects, resembles snow-capped mountains and evokes the early history of Colorado when Native American teepees were located across the Great Plains. The catenary steel cable system, similar to the Brooklyn Bridge design supports the fabric roof. DIA is also known for a pedestrian bridge connecting the terminal to Concourse A that allows travelers to view planes taxiing beneath them and has views of the Rocky Mountains to the West and the high plains to the East.

Art

Both during construction and after opening, DIA has set aside a portion of its construction and operation budgets for art. Gargoyles hiding in suitcases are present above exit doors from baggage claims. The corridor from the main terminal and Concourse A usually contains additional temporary exhibits. Finally, a number of different public art works are present in the underground train that links the main terminal with concourses.

Blue Mustang

Blue Mustang, by El Paso born artist Luis Jiménez, was one of the earliest public art commissions for Denver International Airport in 1993. The 32 feet (9.8 m) tall Blue Mustang is a bright blue cast-fiberglass sculpture with glowing red eyes located between the inbound and outbound lanes of Peña Boulevard.[9] Jiménez was killed in 2006 at age 65 while creating the sculpture when part of it fell on him and severed an artery in his leg. At the time of his death, Jiménez had completed painting the head of the mustang. Blue Mustang was completed by others, and unveiled at the airport on February 11, 2008.[10] The statue has been the subject of considerable controversy.[11][12]

Other

Other DIA Art Commissions have been awarded to artists Leo Tanguma, Gary Sweeney,[13] and Gary Yazzie.[14]

DIA's Art Collection was recently honored by the publishers of USA TODAY, for being of the ten best airports for public art[15] in the United States.

The airport also features a bronze statue of astronaut, Congressman-elect and Denver native Jack Swigert. Swigert, who flew on Apollo 13 as Command Module Pilot, was elected to the House of Representatives in 1982, but died of cancer before he was sworn in. The statue is dressed in an A7L pressure suit, and is posed holding a gold-plated helmet. It is a duplicate of a statue placed at the United States Capitol in 1997.[16]

Automated baggage system

The airport's defunct computerized baggage system, which was supposed to reduce delays, shorten waiting times at luggage carousels, and cut airline labor costs, was an unmitigated failure. The airport opening was originally scheduled for October 31, 1993, with a single system for all three concourses. Issues with the system delayed the opening to February 28, 1995, with separate systems for each concourse and varying degrees of automation.

The system's $186 million original construction costs grew by $1 million per day during months of modifications and repairs. Incoming flights on the airport's B Concourse made very limited use of the system, and only United, DIA's dominant airline, used it for outgoing flights. The 40-year-old company responsible for the design of the automated system, BAE Automated Systems (formerly Boeing Airport Equipment)[17] of Carrollton, Texas, at one time responsible for 90% of the baggage systems in the United States, was acquired in 2002 by G&T Conveyor Company, Inc.[18]

The automated baggage system never worked as designed, and in August 2005 it became public knowledge that United would abandon the system, a decision that would save them $1 million per month in maintenance costs.[19]

Automated Guideway Transit System

Concourses are accessed by a people mover known as the Automated Guideway Transit System. With four train stations and thirty-one vehicles, it moves passengers between the main terminal and the three concourses via an underground rail system. This system is not part of the commuter rail system between downtown Denver and Denver International Airport.[20]

Solar energy system

Denver International Airport currently has four solar photovoltaic arrays on airport property, with a total capacity of 10 megawatts or 16 million kilowatt-hours of solar electricity annually.[21]

- Solar I

In mid 2008, Denver International Airport inaugurated a $13 million solar farm situated on 7.5 acres directly south of Jeppesen Terminal between Peña Boulevard's inbound and outbound lanes. The solar farm consists of more than 9,200 solar panels that follow the sun to maximize efficient energy production and generate more than 3.4 million kilowatt hours of electricity per year. Owned and run by a specialist independent energy company, Fotowatio Renewable Ventures, its annual output amounts to around 50 percent of the electricity required to operate the train system that runs between the airport's terminal and gate areas.[22] By using this solar-generated power, DEN will reduce its carbon emissions as much as five million pounds each year.

- Solar II

In December 2009, a $7 million, 1.6-megawatt solar project on approximately nine acres north of the airport's airfield went into operation. The array is a project that involves MP2 Capital and Oak Leaf Energy Partners generating over 2.7 million kilowatt-hours of clean energy annually and provides approximately 100 percent of the airport's fuel farm's electricity consumption.[21]

- Solar III

A third solar installation situated on 28 acres, dedicated in July 2011, is a 4.4MW complex, expected to generate 6.9 million kilowatt-hours of energy. Intermountain Electric Inc. built the system, with solar panels provided by Yingli Green Energy. The power array will reportedly reduce CO2 emissions by 5,000 metric tons per year.

- Solar IV

The airport added its fourth solar power array in June 2014. The $6 million system can generate up to 2MW, or 3.1 million kilowatt-hours of solar electricity annually. It is located north of the airfield and provides electricity directly to the Denver Fire Department's Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) Training Academy.[21]

Denver International Airport's four solar array systems now produce approximately six percent of the airport's total power requirements.[23] The output makes DEN the largest distributed generation photovoltaic energy producer in the state of Colorado,[24] and the second-largest solar array among U.S. airports.

Telecommunications

DIA has Wi-Fi access throughout the airport. The free service is provided by the airport directly and is no longer ad-supported.[25] Independent testers have found DIA's Wi-Fi to be among the fastest at any U.S. airport, with average speeds of 61.74 Mbit/s.[26]

Geography

The airport is 25 miles (40 km) driving distance from downtown Denver,[27] which is 19 miles (31 km) farther away than Stapleton International Airport, the airport it replaced.[28] The distant location was chosen to avoid aircraft noise affecting developed areas, to accommodate a generous runway layout that would not be compromised by blizzards, and to allow for future expansion.

The 52.4 square miles (136 km2)[4] of land occupied by the airport is more than one and a half times the size of Manhattan (33.6 sq mi or 87 km2). The land was transferred from Adams County to Denver after a 1989 vote,[29] increasing the city's size by 50 percent and bifurcating the western portion of the neighboring county. As a result, the Adams County cities of Aurora, Brighton, and Commerce City are actually closer to the airport than much of Denver. All freeway traffic accessing the airport from central Denver leaves the city and passes through Aurora, making the airport a practical exclave. Similarly, the A Line rail service connecting the airport with downtown Denver has two intervening stations in Aurora.

History

From 1980 to 1983,[30] the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) investigated six areas for a new metro area airport that were north and east of Denver. In September 1989, under the leadership of Denver Mayor Federico Peña federal officials authorized the outlay of the first $60 million for the construction of DIA. Two years later, Mayor Wellington Webb inherited the megaproject, scheduled to open on October 29, 1993.

Delays caused by poor planning and repeated design changes due to changing requirements from United Airlines caused Mayor Webb to push opening day back, first to December 1993, then to March 1994. By September 1993, delays due to a millwright strike and other events meant opening day was pushed back again, to May 15, 1994.

In April 1994, the city invited reporters to observe the first test of the new automated baggage system. Reporters were treated to scenes of clothing and other personal effects scattered beneath the system's tracks, while the actuators that moved luggage from belt to belt would often toss the luggage right off the system instead. The mayor cancelled the planned May 15 opening. The baggage system continued to be a maintenance hassle and was finally terminated in September 2005,[19] with traditional baggage handlers manually handling cargo and passenger luggage.

On September 25, 1994, the airport hosted a fly-in that drew several hundred general aviation aircraft, providing pilots with a unique opportunity to operate in and out of the new airport, and to wander around on foot looking at the ground-side facilities—including the baggage system, which was still under testing. FAA controllers also took advantage of the event to test procedures, and to check for holes in radio coverage as planes taxied around and among the buildings.

DIA finally replaced Stapleton on February 28, 1995, 16 months behind schedule and at a cost of $4.8 billion,[31] nearly $2 billion over budget.[28] The construction employed 11,000 workers.[32] United Airlines Flight 1062 to Kansas City International Airport was the first to depart and United Flight 1474 from Colorado Springs Airport was the first to arrive.[28]

DIA still owns some land at the former Stapleton site, an open field area bordered by Central Park Blvd to the west, 40th Ave to the North, Havana St. to the East & 37th Ave to the south, with the exception of the Coca-Cola-Swire Warehouse & the FedEx warehouse. The city's department of aviation has continuously owned this site even after Stapleton closed.

After the airport's runways were completed but before it opened, the airport used the codes (IATA: DVX, ICAO: KDVX). DIA later took over (IATA: DEN, ICAO: KDEN) as its codes from Stapleton when the latter airport closed.

During the blizzard of March 17–19, 2003, the weight of heavy snow tore a hole in the terminal's white fabric roof. Over two feet of snow on the paved areas closed the airport (and its main access road, Peña Boulevard) for almost two days. Several thousand people were stranded at DIA.[33][34]

In 2004, DIA was ranked first in major airports for on-time arrivals according to the FAA.

Another blizzard on December 20 and 21, 2006 dumped over 20 inches (51 cm) of snow in about 24 hours. The airport was closed for more than 45 hours, stranding thousands.[35] Following that blizzard, the airport invested heavily in new snow-removal equipment that has led to a dramatic reduction in runway occupancy times to clear snow, down from an average of 45 minutes in 2006 to just 15 minutes in 2014.

On November 19, 2015 the first part of a Hotel and Transit Center, the hotel, opened adjacent to the Jeppesen Terminal. On April 22, 2016, commuter rail service to the Hotel and Transit Center from Denver Union Station began.

Design and expandability

Denver has traditionally been home to one of the busier airports in the nation because of its location. Many airlines including United Airlines, Western Airlines, the old Frontier Airlines and People Express were hubbed at the old Stapleton International Airport, and there was also a significant Southwest Airlines operation. At times, Stapleton was a hub for three or four airlines. The main reasons that justified the construction of the new DIA included the fact that gate space was severely limited at Stapleton, and the Stapleton runways were unable to deal efficiently with Denver's weather and wind patterns, causing nationwide travel disruption. The project began with Perez Architects and was completed by Fentress Bradburn Architects of Denver, Pouw & Associates of Arvada, CO, and Bertram A. Bruton & Associates of Denver.[36][37] The signature DIA profile, suggestive of the snow-capped Rocky Mountains, was first hand-sketched by Design Director Curtis W. Fentress. Seized upon by then Mayor, Federico Peña, as the iconic form he was looking for – "similar to the Sydney Opera House" – DIA's design as well as its user-optimized curbside-to-airside navigation has won DIA global acclaim and propelled its designer, Fentress, to one of the foremost airport designers in the world. Fentress Architects is currently at work on the modernization of LAX. The concourses were designed by a joint venture of The Richardson Associates and The Allred Fisher Seracuse Lawler Partnership.[38]

With the construction of DIA, Denver was determined to build an airport that could be easily expanded over the next 50 years to eliminate many of the problems that had plagued Stapleton International Airport. This was achieved by designing an easily expandable midfield terminal and concourses, creating one of the most efficient airfields in the world.

At 33,531 acres (136 km2),[4] DIA is by far the largest land area commercial airport in the United States. Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport is a distant second at 70 km2 (26.9 square miles). The 327-foot (100 m) control tower is one of the tallest in North America.[39] The airfield is arranged in a pinwheel formation around the midfield terminal and concourses. This layout allows independent flow of aircraft to and from each runway without any queuing or overlap with other runways, as well as allowing air traffic patterns to be adjusted to avoid crosswinds, regardless of wind direction. Additional runways can be added as needed, up to a maximum of 12 runways. Denver currently has four north/south runways (35/17 Left and Right; 34/16 Left and Right) and two east/west runways (7/25 and 8/26).

DIA's sixth runway (16R/34L) is the longest commercial precision-instrument runway in North America with a length of 16,000 feet (4,877 m).[40] Compared to other DIA runways, the extra 4,000-foot (1,200 m) length allows fully loaded jumbo jets such as the Boeing 747 or Airbus A380 to take off in Denver's mile-high altitude during summer months, thereby providing unrestricted global access for any airline using DIA.

The midfield concourses allow passengers to be screened in a central location efficiently and then transported via the underground people mover to three different passenger concourses. Unlike Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport upon which the midfield design was based, Concourses B and C are not connected by any kind of walkway; they are only accessible via train.

The taxiways at Denver have been positioned so that each of the midfield concourses can expand significantly before reaching the taxiways. Concourse B, used by United Airlines, is longer than the other two concourses, and after the addition of four gates to its west end in 2019, it will be at or near its maximum possible length. However, Concourses A and C can be extended to equal the length of Concourse B. Once this expansion is exhausted, space has been reserved for four future Concourses: D and E (by extending the train) and East and West (to be connected via walkways to the Jeppesen Terminal).

All international flights requiring customs and immigration services currently fly into Concourse A. Currently twelve gates are used for international flights. Eight of these are north facing gates on Concourse A equipped to divert incoming passengers to a hallway that connects to the upper level of the air bridge and enters Customs and Immigration in the north side of the Jeppesen Terminal. In 2017, four of the south facing gates on Concourse A were retro-fitted with access to a new sterile hallway which leads upstairs and merges with the hallway from the other eight original gates. See Concourse A below.

As part of the original design of the airport the city specified passenger volume "triggers" that would lead to a redevelopment of the master plan and possible new construction to make sure the airport is able to meet Denver's needs.[41] The city hit its first-phase capacity threshold in 2008, and DIA is currently revising the master plan. As part of the master plan update, the airport announced selection of Parsons Corporation to design a new hotel, rail station and two bridges leading into the main terminal. The airport has the ability to add up to six additional runways, bringing the total number of runways to 12. Once fully built out, DIA should be able to handle 110 million passengers per year, up from 32 million at its opening.

On September 9, 2015, a political campaign was launched by Denver Mayor Michael Hancock to radically expand commercial development at DIA, development previously prohibited by intergovernmental agreement between Denver and Adams County.[42] The changes to the agreement were approved by both Denver and Adams County voters in November 2015.[43]

Terminal and Concourses

Jeppesen Terminal

Jeppesen Terminal, named after aviation safety pioneer Elrey Jeppesen, is the land side of the airport. Road traffic accesses the airport directly off of Peña Boulevard, which in turn is fed by Interstate 70 and E-470. Two covered and uncovered parking areas are directly attached to the terminal – four garages and an economy parking lot on the east side; and four garages and an economy lot on the west side.

The terminal is separated into west and east terminals for passenger drop off and pickup. Linked below is a map of the airlines associated with the terminals.

The central area of the airport houses two security screening areas and exits from the underground train system. The north side of the Jeppesen Terminal contains a third security screening area and a segregated immigration, and customs area.

The main terminal has six official floors, connected by elevators and escalators. Floors 1–3 comprise the lowest levels of the parking garages as well as the economy lots on both sides of the terminal. Floor 4 contains passenger pickup, as well as short-term and long-term parking. Floor 5 is used for parking as well as drop-offs and pick-ups for taxis and shuttles to rental car lots and off-site parking. The fifth floor also contains the baggage carousels and security checkpoints. The sixth floor is used for passenger dropoff and check-in counters.

Passengers are routed first to airline ticket counters or kiosks on the sixth floor for checking in. Since all gates at Denver are in the outlying concourses, passengers clear security at one of three different checkpoints: one at each end of the main terminal, each of which has its own bank of escalators that lead down to the trains; as well as a smaller one at the end of the pedestrian bridge to Concourse A.

After leaving the main terminal via the train or pedestrian bridge, passengers can access 95 full-service gates on 3 separate concourses (A, B, & C), plus gates for regional flights.

Stone used in the terminal walls was supplied by the Yule Marble Quarry, also used for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Lincoln Memorial.[44]

As of April 2018, work has begun inside Jeppesen Terminal on a major interior renovation and reconfiguration including the beginning phases of construction to relocate 2 out of the 3 TSA security checkpoints from the Great Hall on Level 5 to Level 6 (East & West) while simultaneously updating and consolidating airline ticket counters/check-in. Eventually, both pre and post security gathering and leisure areas will be incorporated into the spaces where the TSA security areas on Level 5 are currently located. This phased project to the terminal, along with an ongoing 39-gate expansion project to all three concourses and a few other capital improvement projects, is expected to be completed by 2021 with a total price tag of around $3.5 billion.

Hotel and Transit Center

The DIA Hotel and Transit Center is made up of three integrated functional areas: hotel, public land transportation, and public plaza.

A $544 million construction project was recently completed (April 2016) directly connecting a hotel and transit center to the Jeppesen terminal. The project includes a commuter rail train station, run by Regional Transportation District's (RTD) FasTracks system and a 519-room hotel and conference center, run by Westin Hotels & Resorts. The hotel opened November 19, 2015[45] and the commuter rail service began on April 22, 2016. Gensler and AndersonMasonDale Architects were the architects for the project. The builder of the project was MHS, a tri-venture composed of Mortenson Construction, Hunt Construction and Saunders Construction.[46] Construction had begun on October 5, 2011.[47][48] RTD regional bus bays can be found under the Hotel and and adjacent to the Transit Center and rail lines. The 82,000 square-foot public plaza will be Denver's newest venue for arts and entertainment and will provide an area for travelers and visitors to relax and enjoy art, sunshine and views of the Rocky Mountains.[49] The plaza will be operated by Denver Arts and Venues, the City and County of Denver agency that operates Denver owned entertainment venues. The rail station is located underneath the hotel with a 150 foot (46 m) canopy extending through the plaza north to the Jeppesen Terminal.

Concourses

DIA has three midfield concourses, spaced far apart, though the train stations are no longer named by concourse, instead just denoted as "All __ Gates." Concourse A is accessible via a pedestrian bridge directly from the terminal building, as well as via the underground train system that services all three concourses. For access to Concourses B and C, passengers must utilize the train. Once in 1998 and again once in 2012, the train system encountered technical problems and shut down for several hours, creating tremendous back-logs of passengers in the main terminal since no pedestrian walkways exist between the terminal and the B and C Concourses. On both occasions, buses had to be used because of the train problems.[50]

The concourses and main terminal are laid out similarly to Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The main difference is that DIA has no satellite unit of T gates directly attached to the terminal, and the space between the concourses at DIA is much wider than the space between the concourses in Atlanta. This allows for maximum operating efficiency as aircraft can push back from their gate while other taxiing aircraft can still taxi through the alley behind them without delay.

The airport collects landing fees, rent and other revenues from the airlines to help offset its operating costs. DIA is owned and operated by the City and County of Denver, but does not operate using tax dollars. Instead, the airport is an "enterprise fund" generating its own revenues in order to cover operating expenses. The airport operates off of revenue generated by the airlines – landing fees, rents and other payments – and revenues generated by non-airline resources – parking, concessions revenues, rent and other payments.

On December 14, 2006, DIA instituted the design phase of expanding Concourse C in the airport's first major expansion of a concourse. In September 2014, the airport completed construction of five new gates on the C Concourse, which now serve Southwest Airlines. The new gates are labeled C23 through C27 and expand the space by 39,000 square feet (3,600 m2) at a cost of $46 million.[51]

Concourse B also expanded with the addition of a regional jet terminal designed by Reddy & Reddy Architects at the east side of the concourse.[52] This Regional Jet concourse consists of one smaller concourse or finger that is connected to Concourse B.[53][54] These gates allow direct jet bridge access to smaller Regional Jets. With the opening of the Regional Jet Concourse on April 24, 2007, United Airlines left Concourse A entirely and operates solely from B, with the exception of international flights requiring customs support.[55]

Prompted by growth in routes and passengers, on July 31, 2017, the City Council approved a project management contract to add a total of 26 gates combined to the three existing concourses (A, B & C).[56] In November 2017 that number was revised and increased to 39 additional gates or from the current 137 gates to 176 gates, a 28% increase. The project and the contracts for the architectural and construction work was approved by the Denver city council on November 13, 2017.[57] The gate expansion project mirrors a $1.8 billion phased renovation and reconfiguration to Jeppesen Terminal which began in the spring of 2018 and is expected to finish by 2021. When both the terminal renovation and concourse expansions are completed, the airport should be able to handle between 80 and 90 million passengers per year. The airport is currently (as of 2017[update]) built to handle 50 million passengers and saw over 61 million pass through in 2017, an increase of over 5% from 2016 passenger totals.

Concourse A

Concourse A is 1,900 feet (579 m) long, takes up 1.22 million square feet (113,000 m2)[58] and has 38 gates: A26–A53, A56, A59–65, and A67–68.[59] Twelve of these gates (A33, A35, A37, A39-A47) are equipped to handle international arrivals. Five gates (A31, A33, A37, A41, A45) are equipped to handle wide-body aircraft, of which two (A37 and A41) have twin jet bridges labeled A and B. Concourse A handles all international arrivals at the airport (excluding airports with border preclearance), as well as the departing flights of all international carriers serving Denver. Furthermore, all domestic airlines, except for Alaska, Southwest, Spirit, and United, use this concourse, with Frontier Airlines having the largest presence.

At the time of the airport's opening, Concourse A was to be solely used by Continental Airlines for its Denver hub. However, due to its emergence from bankruptcy, as well as fierce competition from United Airlines, Continental chose to dismantle its hub immediately after the opening, and only operated a handful of gates on A, before eventually moving to Concourse B prior to its merger with United.[60]

Two lounges are located on the top floor of the central section of Concourse A: the shared American Airlines Admirals Club/British Airways Executive Club Lounge, and a Delta Air Lines Sky Club, the latter of which opened in 2016 in the location of the former USO lounge.[61]

In May 2018 construction began on a 12-gate expansion to the west end of Concourse A. The first five gates are expected to be completed by June 2020 with the remaining project to be completed by December 2020. Some of the new gates will be additional gates capable of handling larger wide-body aircraft for international flights with direct access to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. When finished, gate capacity in Concourse A will be increased by nearly 32% to 50 gates.

Concourse B

Concourse B is 3,300 feet (1,006 m) long, takes up 2.03 million square feet (189,000 m2) and has 70 gates: B11 & B14 (both opened Spring 2017), B15–B29, B31–B33, B35–B39, B41–B61, B63–B77 (odd number gates only), and B79–B95.[59] Gates B32, B36, B38, and B42 are equipped with twin jet bridges (with each bridge designated as A or B) to accommodate larger wide-body aircraft. United Airlines is the sole occupant of Concourse B. Mainline United flights operate from the main concourse building, whereas United Express operations are handled at the east end of the concourse (gates B48–B95), which includes two ground-level satellite extensions.

Former tenants of Concourse B include Continental Airlines and US Airways. Both airlines relocated there in November 2009 after United reached an agreement with DIA to allocate five gates at the western end of the concourse for use by its domestic Star Alliance partners. United would regain control of the three Continental gates after the merger between the two airlines. And as in February 2015, US Airways relocated the operations of their two gates to Concourse A as part of its merger process with American Airlines.[62]

There are two United Clubs on the second floor of Concourse B, situated about an equal distance away from the people mover station: one near gate B32 and the other near gate B44.

In May 2018 construction began on an 11-gate expansion to Concourse B. Four gates will be added to the west end and seven gates to the east end. Completion is expected by May 2020. When finished, gate capacity in Concourse B will be increased by nearly 16% to 81 gates.

Concourse C

Concourse C is 1,900 feet (579 m), takes up 0.79 million square feet (73,000 m2) and has 29 gates: C23–C51. Southwest Airlines is the primary occupant of the concourse (25 dedicated gates), with only two other airlines: Alaska Airlines and Spirit Airlines utilizing the concourse. A recent expansion added five new gates (C23–27) to the west end of the concourse. The expansion, which was completed in September 2014 at a cost of $46 million, allowed Southwest to consolidate all of its operations onto Concourse C (prior to the expansion, Southwest was using two gates on Concourse A, which it had inherited from its merger with AirTran Airways).[63]

In May 2018 construction began on a 16-gate expansion to the east end of Concourse C. The project is expected to be completed by January 2021. When finished, gate capacity in Concourse C will be increased by nearly 55% to 45 gates.

Future Concourses D, E, East & West

The airport has reserved room for two more Concourses to be built beyond Concourse C for future expandability. Concourse D can be built without having to move any existing structure. The underground train system, however, will have to be extended. Concourse E will require moving a United Airlines hangar. However, before construction on Concourses D and E begins, Concourses A, B, and C can be extended in both directions. But with gate expansions to all three concourses actively happening - set to be completed by 2021 - each existing concourse will be at near maximum expandability when the gate expansion projects are complete. Also, the 2012 revised master plan has added two new concourses named East & West to be built before Concourses D and E.[64] These new East and West concourses would be built on either side of the existing Jeppesen Terminal beyond the parking garages, where the surface economy parking lots are presently (as of 2017[update]) located. These concourses will not need to use the underground train system; thus, save money and further delay the construction of D & E.

Ground transportation

Numerous transportation options exist for ground access to and from Denver International Airport, including: Charter buses, commuter rail, hotel shuttles, limousines, mountain carriers, public buses, shared-ride services, peer-to-peer transportation services and taxicabs. Most services access on level five of the terminal with public buses and rail access in the Hotel and Transit center. Private vehicle access is on the East or West side of terminal, depending upon airline, with drop-off on level six and pick-up on level four.

The Regional Transportation District (RTD) operates three bus routes under the frequent airport express bus service called skyRide, as well as one Express bus route and one Limited bus route, between DIA and various locations throughout the Denver-Aurora and Boulder metropolitan areas. RTD also operates the University of Colorado A Line, a commuter rail line that runs between the airport and Union Station in Downtown Denver.

The skyRide services operate on comfortable motorcoaches with ample space for luggage, while the Express and Limited bus routes operate on regular city transit buses and are mainly geared for use by airport employees.

| Route | Title | Areas served |

|---|---|---|

| skyRide | ||

| AA | Wagon Road / DIA | Westminster, Northglenn, Thornton, Commerce City |

| AB | Boulder / DIA | Boulder, Louisville, Superior, Broomfield |

| AT | Arapahoe County / DIA | Greenwood Village, Southeast Denver, Central Aurora |

| Limited | ||

| 169L | Buckley / Tower / DIA | South and East Aurora, Northeast Denver |

| Express | ||

| 145X | Brighton / DIA | Brighton |

Scheduled bus service is also available to points such as Fort Collins, Colorado and van services stretch into Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado summer and ski resort areas. Amtrak offers a Fly-Rail plan for ticketing with United Airlines for trips into scenic areas in the Western U.S. via a Denver stopover.

Rail service

The Regional Transportation District's airport rail link is an electric commuter rail line that runs from Denver Union Station to the DIA Hotel and Transit Center. Under a sponsorship agreement called "University of Colorado A Line" and also called the "East Rail Line" connects passengers between downtown Denver and Denver International Airport in about 37 minutes. The line connects to RTD's rail service that runs throughout the metro area. The A Line is a 22.8-mile commuter rail transit corridor connecting these two important areas while serving adjacent employment centers, neighborhoods and development areas in Denver and Aurora. The A Line was constructed and funded as part of the Eagle P3 public-private partnership and opened for service on April 22, 2016.

Airlines and destinations

DEN serves over 195 destinations including 26 international cities in 11 countries: Germany, United Kingdom, Iceland, Japan, France, Canada, Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica, Belize and Switzerland. DIA is the largest hub of Frontier Airlines and the fourth-largest hub for both Southwest Airlines and United Airlines. These three airlines' combined operations made up about 83% of the total passenger traffic at DEN as of December 2017.[3]

Passenger

Cargo

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,275,000 | American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit, United | |

| 2 | 1,030,000 | American, Frontier, Southwest, United | |

| 3 | 1,027,000 | Frontier, Southwest, United | |

| 4 | 992,000 | Frontier, Southwest, Spirit, United | |

| 5 | 975,000 | American, Frontier, Spirit, United | |

| 6 | 904,000 | Alaska, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, United | |

| 7 | 841,000 | Delta, Frontier, Southwest, United | |

| 8 | 824,000 | Delta, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit, Sun Country, United | |

| 9 | 824,000 | American, Frontier, Spirit, United | |

| 10 | 797,000 | Delta, Frontier, Southwest, United |

| Rank | Airport | 2016 Passengers | Annual Change | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 451,619 | Frontier, Southwest, United | ||

| 2 | 218,961 | Air Canada, United | ||

| 3 | 216,713 | Lufthansa | ||

| 4 | 193,136 | British Airways | ||

| 5 | 180,649 | Air Canada, United | ||

| 6 | 169,342 | Frontier, Southwest, United | ||

| 7 | 153,079 | Frontier, United, WestJet | ||

| 8 | 136,916 | United | ||

| 9 | 123,242 | Frontier, Southwest, United | ||

| 10 | 94,452 | Icelandair | ||

| 11 | 68,347 | N/A | Lufthansa | |

| 12 | 60,728 | Aeroméxico, United, Volaris | ||

| 13 | 58,366 | United | ||

| 14 | 50,794 | United | ||

| 15 | 35,198 | Volaris | ||

| 16 | 24,899 | N/A | Air Canada | |

| 17 | 13,949 | N/A | Volaris | |

| 18 | 3,029 | N/A | Aeroméxico | |

| 19 | N/A | N/A | Copa | |

| 20 | N/A | N/A | Norwegian Air Shuttle | |

| 21 | N/A | N/A | United | |

| 22 | N/A | N/A | Southwest | |

| 23 | N/A | N/A | United | |

| 24 | N/A | N/A | Edelweiss | |

| 25 | N/A | N/A | Norwegian Air Shuttle | |

| 26 | N/A | N/A | Sun Country |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Δ | thereof

intern. |

Year | Passengers | Δ | thereof

intern. |

Year | Passengers | Δ | thereof

intern. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 32,296,174 | 1.0% | 2006 | 47,326,506 | 4.0% | 2016 | 58,266,515 | 4.0% | |||||

| 1997 | 34,969,837 | 1.1% | 2007 | 49,863,352 | 4.4% | 2017 | 61,379,396 | 4.2% | |||||

| 1998 | 36,831,400 | 1.4% | 2008 | 51,245,334 | 4.3% | ||||||||

| 1999 | 38,034,017 | 1.9% | 2009 | 50,167,485 | 3.8% | ||||||||

| 2000 | 38,751,687 | 2.2% | 2010 | 51,985,038 | 3.7% | ||||||||

| 2001 | 36,092,806 | 2.3% | 2011 | 52,849,132 | 3.2% | ||||||||

| 2002 | 35,652,084 | 2.2% | 2012 | 53,156,278 | 3.3% | ||||||||

| 2003 | 37,505,267 | 2.5% | 2013 | 52,556,359 | 3.7% | ||||||||

| 2004 | 42,275,913 | 2.9% | 2014 | 53,472,514 | 4.1% | ||||||||

| 2005 | 43,387,369 | 3.7% | 2015 | 54,014,502 | 4.1% |

Airline Market Share

| Rank | Carrier | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United | 25,900,441 | 42.2% |

| 2 | Southwest | 18,230,471 | 29.7% |

| 3 | Frontier | 6,990,526 | 11.4% |

| 4 | American | 3,363,002 | 5.5% |

| 5 | Delta | 3,292,733 | 5.4% |

| 6 | Spirit | 1,176,927 | 1.9% |

| - | Other airlines | 2,425,296 | 3.9% |

Accidents and incidents

- On September 5, 2001, a British Airways Boeing 777 caught on fire while it was being refueled at the gate. None of the deplaning passengers or crew were injured, but the refueler servicing the aircraft died from his injuries six days after the fire. The NTSB found that the accident occurred due to a failure of the aircraft's refueling ring when the fuel hose was torn out of it at an improper angle.[103]

- On February 16, 2007, 14 aircraft suffered windshield failures within a three-and-a-half-hour period at the airport. A total of 26 windshields on these aircraft failed. The NTSB opened an investigation, determining that foreign object damage was the cause, possibly the sharp sand used earlier that winter for traction purposes combined with wind gusts of 48 mph (77 km/h).[104]

- On December 20, 2008, a Continental Airlines Boeing 737-500 operating as Flight 1404 to Houston–Intercontinental Airport in Houston, TX, veered off the left side of runway 34R, and caught fire, during its takeoff roll at Denver International Airport. There was no snow or ice on the runway, however there were 31 knot (36 mph) crosswinds at the time of the accident. On July 13, 2010 the NTSB published that the probable cause of this accident was the captain's cessation of right rudder input, which was needed to maintain directional control of the airplane. Of the 115 people on board, at least 38 sustained injuries: at least two of these injured critically.[105][106][107]

- On April 3, 2012, an ExpressJet Embraer ERJ-145, registration N15973, operating as Flight UA/EV-5912 from Peoria, IL to Denver, CO, was landing on 34R when the aircraft hit the approach lights and stopped on the runway. Smoke developed inside the aircraft and passengers were evacuated onto the runway. One passenger was taken to hospital for treatment of his injuries.[108]

- On July 2, 2017, one of the engines on SkyWest Flight 5869, operating under the United Express brand name caught fire after landing from Aspen. All 59 passengers and 4 crew members were safely evacuated from the CRJ-700. No injuries were reported.[109]

Conspiracies and controversy

There are several conspiracy theories relating to the airport's design and construction such as the runways being laid out in a shape similar to a swastika. Murals painted in the baggage claim area have been claimed to contain themes referring to future military oppression and a one-world government. However, the artist, Leo Tanguma, said the murals, titled "In Peace and Harmony With Nature" and "The Children of the World Dream of Peace," depict man-made environmental destruction and genocide along with humanity coming together to heal nature and live in peace.[110]

Conspiracists have also seen unusual markings in the terminals in DIA and have recorded them as "Templar" markings.[111] They have pointed to unusual words cut into the floor as being Satanic, Masonic,[112] or some impenetrable secret code of the New World Order: Cochetopa, Sisnaajini and Dzit Dit Gaii. Two of these words are actually misspelled Navajo terms for geographical sites in Colorado. "Braaksma" and "Villarreal" are actually the names of Carolyn Braaksma and Mark Villarreal, artists who worked on the airport's sculptures and paintings.[113]

There is a dedication marker in the airport inscribed with the words "New World Airport Commission". It also is inscribed with the Square and Compasses of the Freemasons, along with a listing of the two Grand Lodges of Freemasonry in Colorado. It is mounted over a time capsule that was sealed during the dedication of the airport, to be opened in 2094.[114]

Robert Blaskiewicz writing for Skeptical Inquirer states that conspiracies about the airport range from the "absurd to the even more absurd". When asking airport media representatives about which conspiracies are associated with the airport, he was told: "You name a conspiracy theory and somehow we seem to be connected to it." Blaskiewicz found that contrary to claims from conspiracy theorists that DIA will not discuss these stories with the public, they also give tours of the airport.[115]

Denver and jurisdictions surrounding the airport are involved in a protracted dispute over how to develop land around the facility. Denver Mayor Michael Hancock wants to add commercial development around the airport, but officials in Adams County believe doing so violates the original agreement that allowed Denver to annex the land on which the airport sits.[116]

See also

- Busiest airports in the United States by international passenger traffic

- Busiest airports in the United States by total passenger boardings

- List of airports in the Denver area

- List of the busiest airports in the United States

- Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition

- World's busiest airports by passenger traffic

- World's busiest airports by traffic movements

- World's busiest airports by cargo traffic

- World's busiest airports by international passenger traffic

References

- ^ 2013 Economic Impact Study for Colorado Airports (PDF) (Report). Colorado Department of Transportation, Division of Aeronautics. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ "Denver airport – Economic and social impact". Ecquants. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Denver International Airport Total Operations and Traffic" (PDF). City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. December 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c FAA Airport Form 5010 for DEN PDF

- ^ Schilling, David Russell (August 26, 2013). "Denver Airport 2nd Largest In The World, Twice the Size of Manhattan". Industry Tap. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Five Years in a Row". Wingtips. 1 (10). City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Zoglin, Richard; Donnelly, Sally B. (July 15, 2002). "Airport Security: Welcome to America's Best Run Airport". Time Magazine. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ "Managing the Environment at Denver International Airport – 2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Denver International Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mustang". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Mustang/Mesteño by Luis Jiménez". City of Denver. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Despite criticism, airport's 'Devil Horse' sculpture likely to stay". NBC News. March 4, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "Keep remarkable "Mustang" sculpture at DIA". The Denver Post. February 6, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "Traveler Information". Denver International Airport. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gary Yazzie: Ronald and Susan Dubin Fellowship". Native Artists. Sante Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "10 Best Airports for Art". USA Today.

- ^ "U.S. Capitol Visitor Center Statues". Visit the Capitol. United States Capitol. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Myerson, Allen (March 18, 1994). "Automation Off Course in Denver". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "G&t Conveyor Of Tavares Buys British Company". Orlando Sentinel. June 20, 2002. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Johnson, Kirk (August 27, 2005). "Denver Airport Saw the Future. It Didn't Work". The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "A Line to the Airport – Arriving Spring 2016". RTD-Denver. Regional Transportation District. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Energy Management". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Fly Green: Denver International To Get Big Solar Array". Ecotality Life. October 5, 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Destination Clean Energy: Denver International Airport Dedicates 4.4 MW of Solar Power from Constellation Energy" (Press release). Constellation Energy. July 28, 2011. Archived from the original on September 20, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Earth Day 2012 at Denver International Airport" (PDF) (Press release). Denver International Airport. April 16, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Wi-Fi". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ "Denver International Airport has nation's fastest public Wi-Fi speeds — and it's free". Denver Post. Denver. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "Distance From Downtown Denver As Per MapQuest". MapQuest. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ayres, Jr., B. Drummond (March 1, 1995). "Finally, 16 Months Late, Denver Has a New Airport". The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ Goetz, Andrew R.; Szyliowicz, Joseph S. (1997). "Revisiting Transportation Planning and Decision Making Theory: The Case of Denver International Airport". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 31 (4): 270. doi:10.1016/S0965-8564(96)00033-X. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Metro Airport Study: Final Report. Denver Regional Council of Governments; Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co. 1983.

- ^ "Denver International Airport Construction and Operating Costs". University of Colorado at Boulder Government Publications Library. July 5, 1997. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dear, Joseph A., Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health (April 11, 1995). Rocky Mountain Health & Safety Conference (Speech). John Q. Hammons Trade Center, Denver, Colorado. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

{{cite speech}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hake, Tony. "This week in Denver weather history: March 11 to March 17". Examiner. AXS Digital Group.

Denver International Airport was closed...stranding about 4000 travelers. The weight of the heavy snow caused a 40-foot gash in a portion of the tent roof...forcing the evacuation of that section of the main terminal building.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "DIA Evacuates Main Terminal For Fear Of Roof Collapse". KMGH-TV. Denver, Colorado. March 19, 2003. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Sink, Mindy (December 22, 2006). "Thousands Stranded in Denver Airport and Environs After Blizzard". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Fentress, Curtis (2010). "Denver International Airport Passenger Terminal Complex". Touchstones of Design: (Re)Defining Public Architecture. Mulgrave, Australia: The Images Publishing Group Pty. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-864-70382-5. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ Moore, Paula (December 28, 2007). "Fentress Architects' DIA Work Opened Global Doors". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "Spotlight". The Denver Post. January 27, 1992. p. 7C. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Denver International Airport Research Center: Aviation Facilities". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "LONGEST – Commercial Runway in North America, DIA – Denver, CO". Waymarking.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Airport Master Plan". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Yes on 1A for DIA – Not so fast". North Denver News. September 9, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Denver Voters OK National Western DIA Ballot Measures". Colorado Statesman. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Denver International Airport Press Kit" (PDF). Denver International Airport. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Denver International Airport and the Westin Announces November 19 Opening Date for the new Westin Denver International airport" (PDF) (Press release). Denver International Airport. June 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hotel and Transit Center — Business Opportunities". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Proctor, Cathy (October 3, 2011). "Signs of Construction at DIA's South Terminal Project". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ "DIA Ground Transportation Level Detours Take Effect Saturday" (PDF) (Press release). Denver International Airport. May 18, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Hotel & Transit Center". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ Painter, Kristen (October 12, 2012). "DIA: 10,000 passengers impacted by problem with trains". The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Proctor, Cathy (September 19, 2014). "DIA opens 5 new gates for Southwest Airlines; will provide Apple iPads". Denver Business Journal. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "United Airlines Regional Jet Facility". Construction Market Data. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "United Airlines – Denver International Airport". United Airlines. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Terminal Maps: Denver International Airport (DEN)". United Airlines. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Mayor Hickenlooper and Other Officials Get Preview of DIA's New Regional Jet Facility" (PDF) (Press release). Denver International Airport. April 23, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ Murray, Jon (August 1, 2017). "DIA prepares for 26-gate expansion blitz by hiring project manager". The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ "Denver council gives blessing to $2 billion city budget and $1.5 billion gate expansion at DIA". November 14, 2017.

- ^ "Gate Areas - Denver International Airport". www.flydenver.com.

- ^ a b "Map of Denver International Airport". flydenver.com. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ "Sources: Continental may increase presence at DIA". USA Today. Associated Press. March 9, 2003. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Delta Sky Club News & Updates". Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Denver, CO (DEN) Airport information". American Airlines. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Construction of Concourse C Expansion Starts at Denver International Airport". Airport World Magazine. September 17, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Master Plan Update Studies Executive Summary" (PDF). flydenver.com. City and County of Denver Department of Aviation. March 31, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Flight Schedule". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "Flight Schedules". Air Canada.

- ^ "Flight Timetable". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Flight schedules and notifications". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "Flight schedules and notifications". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Route Map and Schedule". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Timetables". British Airways.

- ^ "Flight Schedule". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ "Timetable". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ http://wglt.org/post/frontier-airlines-returning-central-illinois-regional-airport#stream/0

- ^ http://www.wtoc.com/story/38450411/the-greenville-spartanburg-international-airport-is-adding-a-sixth-airline

- ^ "Frontier Airlines returns to Harrisburg International Airport with flights to Denver, Orlando and Raleigh/Durham". Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Frontier Airlines August 2018 new routes additions". Routes Online. May 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "Frontier schedules additional new routes in 3Q18". Routes Online. May 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Frontier Airlines returns to Wichita; will fly to Denver".

- ^ http://www.news10.com/news/local-news/frontier-airlines-coming-to-albany-international-airport/1248685206#

- ^ "Frontier". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Timetables" (PDF). Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ "Flight Schedule". Icelandair.

- ^ "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Destinations - Denver Air Connection". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa.

- ^ Zelinger, Marshall (June 11, 2018). "Denver to Paris flight scaled back, but Norwegian Air still gets incentives". 9news.com. KUSA-TV. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Norwegian Air Shuttle Destinations". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Southwest Airlines plans new routes addition in August 2018". Routes Online. February 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ "Southwest schedules new routes in Nov 2018". Routes Online. June 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Southwest Begins Nonstop Service Between Memphis & Denver In October". March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Check Flight Schedules". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Where We Fly". Spirit Airlines. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Sun Country Airlines". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "Timetable". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Volaris Flight Schedule". Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Flight schedules". Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ "Denver, CO: Denver International (DEN)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Aviation and International Affairs (June 20, 2017). U.S.-International Passenger Raw Data for Calendar Year 2016 (Report). US Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "Passenger Traffic Reports". Denver International Airport. City & County of Denver Department of Aviation. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ Denver International Airport, [1]. Accessed February 14, 2018.

- ^ "NTSB Report DEN01FA157". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "NTSB Report DEN07IA069". National Transportation Safety Board. June 27, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Simpson, Kevin; Bunch, Joey; Pankratz, Howard (December 21, 2008). "Continental Jet Veers Off Runway on Takeoff, Slams into Ravine, Catches Fire". The Denver Post. p. A1. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Continental Flight Slides Off Runway; Dozens Injured". KUSA. December 21, 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "NTSB Begins Investigation into Why Plane Slid Off Runway". KUSA. December 21, 2008. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hradecky, Simon (April 3, 2012). "Accident: Expressjet E145 at Denver on Apr 3rd 2012, Smoke in Cockpit, Hard Short Landing". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ Abadi, Mark (July 2, 2017). "Passenger jet catches on fire at Denver airport". Business Insider. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ Jacang Maher, Jared (August 30, 2007). "DIA Conspiracies Take Off". Denver Westword. Retrieved July 11, 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "The Mysterious Masonic Murals of New Denver Airport". The Watcher Files. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Denver Airport Underground Base and Weird Murals". Anomalies Unlimited. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ Hodapp, Christopher (2008) [2008]. Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-470-18408-0.

- ^ Wenzel, John (October 31, 2016). "The definitive guide to Denver International Airport's biggest conspiracy theories". Denver Post. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ^ Blaskiewicz, Robert (April 11, 2012). "The Denver International Airport Conspiracy". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ "Aurora Mayor Steve Hogan blasts Denver's DIA revenue-sharing plan". Denver Post. June 6, 2013.

External links

- Denver International Airport, official site

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective December 26, 2024

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KDEN

- ASN accident history for DEN

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KDEN

- FAA current DEN delay information

- Mysterious Murals and Monuments at the Denver Airport