Fortress of Mimoyecques

| Fortress of Mimoyecques Wiese Bauvorhaben 711 Marquise-Mimoyecques | |

|---|---|

| Mimoyecques, near Landrethun-le-Nord (France) | |

Reconstructed view of the installation as originally planned | |

| Coordinates | 50°51′14″N 1°45′32″E / 50.854°N 1.759°E |

| Type | Bunker |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Website | www |

| Site history | |

| Built | September 1943 – July 1944 |

| Built by | Organisation Todt |

| In use | Never completed, captured 1944 |

| Materials | 150,000 cubic metres concrete |

| Battles/wars | Operation Crossbow |

| Events | Critically damaged 6 July 1944; Captured 5 September 1944; Opened as museum 1984, reopened 1 July 2010 |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | Abteilung 705 (Template:Lang-en 705) [1] |

The Fortress of Mimoyecques VI is the modern name for a Second World War underground military complex built by the forces of Nazi Germany between 1943 and 1944. It was intended to house a battery of V-3 cannons aimed at London, 165 kilometres (103 mi) away. Originally codenamed Wiese ("Meadow") or Bauvorhaben 711 ("Construction Project 711"),[2] it is located in the commune of Landrethun-le-Nord in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France, near the hamlet of Mimoyecques (Template:IPA-fr) about 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Boulogne-sur-Mer. It was constructed by a mostly German workforce recruited from major engineering and mining concerns, augmented by prisoner-of-war slave labour.

The complex consists of a network of tunnels dug under a chalk hill, linked to five inclined shafts in which 25 V-3 guns would have been installed, all targeted on London. The guns would have been able to fire ten dart-like explosive projectiles a minute – 600 rounds every hour – into the British capital, which Winston Churchill later commented would have constituted "the most devastating attack of all".[3] The Allies knew nothing about the V-3 but identified the site as a possible launching base for V-2 ballistic missiles, based on reconnaissance photographs and fragmentary intelligence from French sources.

Mimoyecques was targeted for intensive bombardment by the Allied air forces from late 1943 onwards. Construction work was seriously disrupted, forcing the Germans to abandon work on part of the complex. The rest was partly destroyed on 6 July 1944 by No. 617 Squadron RAF, which used ground-penetrating 5,400-kilogram (12,000 lb) "Tallboy" earthquake bombs to collapse tunnels and shafts, entombing hundreds of slave workers underground.

The Germans halted construction work at Mimoyecques as the Allies advanced up the coast following the Normandy landings. It fell to the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division on 5 September 1944 without resistance, a few days after the Germans withdrew from the area.[4]

The complex was partly demolished just after the war on Churchill's direct orders (and to the great annoyance of the French, who were not consulted), as it was still seen as a threat to the United Kingdom. It was later reopened by private owners, first in 1969 to serve as a mushroom farm and subsequently as a museum in 1984. A nature conservation organisation acquired the Fortress of Mimoyecques in 2010 and La Coupole, a former V-2 rocket base turned museum near Saint-Omer, took over its management. It continues to be open to the public as a vast underground museum complex.[5]

Background

In May 1943 Albert Speer, the Reich's Minister of Armaments and War Production, informed Adolf Hitler of work that was being carried out to produce a supergun capable of firing hundreds of shells an hour over long distances. The newly designed gun, codenamed the Hochdruckpumpe ("High Pressure Pump", HDP for short) and later designated as the V-3, was one of the V-weapons – Vergeltungswaffen ("retaliation weapons") – developed by Nazi Germany in the later stages of the war to attack Allied targets. Long-range guns were not a new development, but the high-pressure detonations used to fire shells from previous such weapons, including the Paris gun, rapidly wore out their barrels.

In 1942, August Coenders, inspired by previous designs of multi-chamber guns, suggested that the gradual acceleration of the shell by a series of small charges spread over the length of the barrel might be the solution to the problem of designing very long-range guns. Coenders proposed the use of electrically activated charges to eliminate the problem of the premature ignition of the subsidiary charges experienced by previous multi-chamber guns. The HDP would have a smooth barrel over 100 metres (330 ft) long, along which a 97-kilogram (214 lb) finned shell (known as the Sprenggranate 4481) would be accelerated by numerous small low-pressure detonations from charges in branches off the barrel, each fired electrically in sequence.[6] Each barrel would be 15 cm (5.9 in) in diameter.[7]

The gun was still in its prototype stages, but Hitler was an enthusiastic supporter of the idea and ordered that maximum support be given to its development and deployment. In August 1943 he approved the construction of a battery of HDP guns in France to supplement the planned V-1 and V-2 missile campaigns against London and the south-east of England.[8] Speer noted afterwards:

On my suggestion, the Führer has decided that the risk must be stood to award contracts at once for the "high-pressure pump," without waiting for the results of firing trials. Maximum support is to be accorded to the experimental ranges at Hillersleben and Misdroy, and especially to the completion of the actual battery.[9]

To reach England, the weapon needed barrels 127 metres (417 ft) long, so it could not be moved; it would have to be deployed from a fixed site.[10] A study carried out in early 1943 had shown that the optimal location for its deployment would be within a hill with a rock core into which inclined drifts could be tunneled to support the barrels.[2]

The site was identified by a fortification expert, Major Bock of the Festungs-Pionier-Stab 27[notes 1] of the Fifteenth Army LVII Corps based in the Dieppe area.[4] A limestone hill near the hamlet of Mimoyecques, 158 metres (518 ft) high and 165 kilometres (103 mi) from London, was chosen to house the gun. It had been selected with care; the hill in which the facility was built is primarily chalk with very little topsoil cover, and the chalk layer extends several hundred metres below the surface, providing a deep but easily tunnelled rock layer. The chalk is easy to excavate and strong enough to dig tunnels without using timber supports. Although the site's road links were poor, it was only a few kilometres west of the main railway line between Calais and Boulogne-sur-Mer.[11]

The area was already heavily militarised; as well as the fortifications of the Atlantic Wall on the cliffs of Cap Gris Nez to the northwest, there was a firing base for at least one[12] conventional Krupp K5 railway gun about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) to the south in the nearby quarries of Hidrequent-Rinxent.[13]

Design and construction

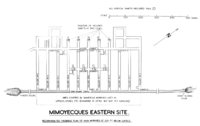

Construction began in September 1943 with the building of railway lines to support the work, and excavation of the gun shafts began in October. The initial layout comprised two parallel complexes approximately 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) apart, each with five drifts which were to hold a stacked cluster of five HDP gun tubes, for a total of 25 guns. The smoothbore design of the HDP would enable a much higher rate of fire than was possible with conventional guns. The entire battery would be able to fire up to 10 shots a minute, capable in theory of hitting London with 600 projectiles every hour. Both facilities were to be served by an underground railway tunnel of standard gauge,[notes 2] connected to the Calais-Boulogne main line,[notes 3] and underground ammunition storage galleries which were tunneled at a depth of about 33 m (108 ft). The western site was abandoned at an early stage after being disrupted by Allied bombing, and only the eastern complex was built.[2][14]

The drifts were angled at 50 degrees, reaching a depth of 105 m (344 ft). Owing to technical problems with the gun prototype, the scope of the project was reduced;[2] drifts I and II were abandoned at an early date and only III, IV and V were taken forward. They came to the surface at a concrete slab or Platte 30 m (98 ft) wide and 5.5 m (18 ft) thick, in which there were narrow openings to allow the projectiles to pass through. The openings in the slab were protected by large steel plates, and the railway tunnel entrances were further protected by armoured steel doors.[15] Each drift was oriented on a bearing of 299°, to the nearest degree – a direct line on Westminster Bridge. Although the elevation and direction of the guns could not be changed, it would have been possible to alter the range by varying the amount of propellant used in each shot. This would have brought much of London within range.[16]

The railway tunnel ran in a straight line for a distance of about 630 m (2,070 ft) . Along its west side was an unloading platform which gave access to ten cross galleries (numbered 3–13 by the Germans), driven at right angles to the main tunnel at intervals of 24 metres (79 ft). Each gallery was fitted with a 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge railway track. On the east side of the tunnel were chambers intended to be used as store rooms, offices and quarters for the garrison. Trains would have entered the facility and unloaded shells and propellant for the guns.[17]

Galleries 6–10, the central group, gave access to the guns, while galleries 3–5 and 11–13 were intended for use as access tunnels and perhaps also storage areas. They were all connected by Gallery No. 2, which ran parallel to the main railway tunnel at a distance of 100 metres (330 ft). Galleries 6–10 were additionally connected by a second passageway, designated Gallery No. 1, running parallel to the main tunnel at a distance of 24.5 metres (80 ft).[17] Further workings existed at depths of 62 m (203 ft), 47 m (154 ft) and 30 m (98 ft), each serving different purposes associated with the drifts and the guns. The 62 m workings were constructed to facilitate the removal of spoil from the drifts, while those at 47 m were connected with the handling of exhaust gases from the guns and those at 30 m gave access to the breeches of the guns.[15] The lower levels of the workings were accessed via lift shafts, and mining cages were used during construction.[16]

The construction work was carried out by over 5,000 workers, mostly German engineers drafted in from several companies including Mannesmann, Gute Hoffnungshütte, Krupp and the Vereinigte Stahlwerke, supplemented by 430 miners recruited from the Ruhr and Soviet prisoners of war who were used as slave labourers.[18] The intensive Allied bombing campaign caused delays, but construction work continued nonetheless at a high pace underground. The original plans had envisaged having the first battery of five guns ready by March 1944 and the full complement of 25 guns by 1 October 1944, but these target dates were not met.[2]

Discovery and destruction

In 1943 French agents reported that the Germans were planning to mount an offensive against the United Kingdom that would involve the use of secret weapons resembling giant mortars sunk in the ground and served by rail links.[19] The first signs of abnormal activity at Mimoyecques were spotted by analysts at the Allied Central Interpretation Unit in September 1943, when aerial reconnaissance revealed that the Germans were building railway loops leading to the tunnels into the eastern and western sites. Further reconnaissance flights in October 1943 photographed large-scale activity around the tunnels.[20]

An analyst named André Kenny discovered a series of shafts when he saw from a reconnaissance photograph that a haystack concealing one of them had disintegrated, perhaps through the effects of a gale, revealing the entrance, a windlass and pulley.[13] The purpose of the site was unclear, but it was thought to be some kind of shelter for launching rockets or flying bombs. An MI6 agent reported that "a concrete chamber was to be built near one of the tunnels for the installation of a tube, 40 to 50 metres long, which he referred to as a 'rocket launching cannon'".[21] The shafts were interpreted as "air holes to allow for the expansion of the gases released by the explosion of the launching charge."

The Allies were unaware of the HDP gun and therefore of the Mimoyecques site's true purpose. Allied intelligence believed at the time that the V-2 rocket had to be launched from tubes or "projectors", so it was assumed that the inclined shafts at Mimoyecques were intended to house such devices.[21]

The lack of intelligence on Mimoyecques was frustrating for those involved in Operation Crossbow, the Allied effort to counter the V-weapons. On 21 March 1944 the British Chiefs of Staff discussed the shortage of intelligence but were told by Reginald Victor Jones, one of the "Crossbow Committee" members, that little information was leaking out because the workforce was predominantly German. The Committee's head, Duncan Sandys, pressed for greater efforts and proposed that the Special Operations Executive be tasked to kidnap a German technician who could be interrogated for information. The suggestion was approved, but was never put into effect.

In the end the Chiefs of Staff instructed General Eisenhower to begin intensive attacks on the so-called "Heavy Crossbow" sites, including Mimoyecques, which was still believed to be intended for use as a rocket-launching site.[21]

The Allied air forces carried out several bombing raids on Mimoyecques between November 1943 and June 1944 but caused little damage.[10] The bombing disrupted the construction project and the initial raids of 5 and 8 November 1943 caused work to be delayed for about a month. The Germans subsequently decided to abandon the western site, where work had not progressed very far, and concentrated on the eastern site.[4] On 6 July 1944 the Royal Air Force began bombing the site with ground-penetrating Tallboy bombs. One Tallboy hit the concrete slab on top of Drift IV, collapsing the drift. Three others penetrated the tunnels below and substantially damaged the facility, causing several of the galleries to collapse in places.[10]

Around 300 Germans and forced labourers were buried alive by the collapses.[22] Adding to the Germans' difficulties, major technical problems were discovered with the HDP gun projectiles. They had been designed to exit the barrels at a speed of about 1,500 m (4,900 ft) per second, but the Germans found that a design fault caused the projectiles to begin "tumbling" in flight at speeds above 1,000 m (3,300 ft) per second, causing them to fall well short of the target. This was not discovered until over 20,000 projectiles had already been manufactured.[7]

After the devastating raid of 6 July, the Germans held a high-level meeting on the site's future at which Hitler ordered major changes to the site's development. On 12 July 1944 he signed an order instructing that only five HDP guns were to be installed in a single drift. The two others were to be reused to house a pair of Krupp K5 artillery pieces, reamed out to a smooth bore with a diameter of 310 millimetres (12 in), which were to use a new type of long-range rocket-propelled shell. A pair of Rheinbote missile launchers were to be installed at the tunnel entrances. These plans were soon abandoned as Allied ground forces advanced towards Mimoyecques, and on 30 July the Organisation Todt engineers were ordered to end construction work.[23]

The Allies were unaware of this and mounted further attacks on the site as part of the United States Army Air Forces experimental Operation Aphrodite, involving radio-controlled B-24 Liberators packed with explosives. Two such attacks were mounted but failed; in the second such attack, on 12 August, Lt Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. – the elder brother of future US President John F. Kennedy – was killed when the drone aircraft exploded prematurely.[22] By the end of the bombing campaign, over 4,100 tons of bombs had been dropped on Mimoyecques, more than on any other V-weapons site.[19]

The Mimoyecques site was never formally abandoned, but German forces left it at the start of September 1944 as the Allies advanced northeast from Normandy towards the Pas de Calais. It was captured on 5 September by the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division.[2]

Subsequent investigations and attempted demolition

In September 1944, Duncan Sandys ordered the constitution of a Technical Inter-Services Mission under Colonel T.R.B. Sanders. It was given the task of investigating the V-weapons sites at Mimoyecques, Siracourt, Watten, and Wizernes, collectively known to the Allies as the "Heavy Crossbow" sites. Sanders' report was submitted to the War Cabinet on 19 March 1945.[24]

Even at this stage the true purpose of the site was unclear. Claims that it had been intended to be used for "electro-magnetic projectors" (railguns), firing huge shells at London, were debunked by Lord Cherwell, Winston Churchill's scientific adviser, who calculated that it would take sixty times the output of Battersea Power Station to fire a one-ton shell. Sanders' investigation brought to light the V-3 project for the first time, to the alarm of the British government. He concluded that although the site had been damaged it "could be completed or adapted for offensive action against this country at some future date, and [its] destruction is a matter of importance."[25] Sandys brought the matter to the attention of Churchill and advised: "Since this installation constitutes a potential threat to London, it would be wise to ensure that it is demolished whilst our forces are still in France."[24] Churchill later commented that the V-3 installation at Mimoyecques "might well have launched the most devastating attack of all on London."[3]

The discovery of the site's true purpose produced some recriminations in London, as – unlike the V-1 and V-2 projects – the V-3 had not been uncovered by Allied intelligence before the war's end. The British scientist and military intelligence expert Reginald Victor Jones later commented that "techniques that had been used against the flying bomb and the rocket appeared to have failed against HDP [V-3], and there had to be a reason. Basically it was that with our limited effort we had to concentrate on the most urgent problem, and thus on catching weapons not so much at the research stage (although we sometimes achieved this) as in the development stage – which usually meant when trials were showing promise." He concluded at the time, in April 1945, that the intelligence failure had not made much practical difference given the fact that the Germans had failed to develop the HDP into an effective weapon: "there was little warning; [but] there was little danger."[7]

Following the recommendation that the site should be destroyed, the Royal Engineers stacked ten tons of British 500 lb (230 kg) bombs and captured German plastic explosive in the tunnels at Mimoyecques and detonated them on 9 May. This failed to achieve the desired effect, and on 14 May, a further 25 tons of explosives were used to bring down the north and south entrances to the railway tunnel into the site. A subsequent investigation by the British Bombing Research Mission concluded that the entrances had been heavily blocked and that it would be a very difficult and lengthy engineering task to reinstate them.[6] The British action was taken without informing the French beforehand and infuriated Charles de Gaulle, who considered it a violation of France's national sovereignty.[26]

Reopening as a museum

After the war, the Mimoyecques site lay abandoned. Much of the equipment left by the Germans was disposed of as scrap metal. A complete set of four steel plates,[12] weighing 60 tons, that were intended to protect the entrances to the drifts were bought by the manager of the Hidrequent-Rixent quarries to be cut up for use in rock-crushing machinery.[6] Rediscovered by local historians in the 1990s,[12] they remained at the quarries until 2010, when the surviving plates were returned to Mimoyecques, where they are now on display.[27]

Despite the closure of the railway tunnel entrances it was still possible for many years to get into the complex by climbing down one of the inclined drifts.[6] In 1969, Marie-Madeleine Vasseur, a farmer from Landrethun, had the southern entrance excavated so that the tunnels could be used as a mushroom farm.[28] 30 metres (98 ft) of the southern tunnel had to be removed to clear the blockage; the entrance now visible is not the original one built by the Germans.[29] The southern entrance had been bricked up again by the 1970s.[6] Moved to discover this forgotten construction, Vasseur, helped by family and friends, cleared the tunnels and installed an electricity supply. The société à responsabilité limitée "La Forteresse de Mimoyecques" was constituted in 1984 to operate the site as a museum under the name of Forteresse de Mimoyecques — Un Mémorial International.[30]

The museum closed at the end of the 2008 season when the owner retired. Subsequently, the nonprofit organisation Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et Pas-de-Calais[31] (Conservatory of natural sites of the Nord and Pas-de-Calais) purchased it at a cost of €330,000, with funding provided by the Nord-Pas-de-Calais regional council, the European Union and a private benefactor.[5] The Conservatory's interest was due to the presence on the site of a large bat colony[32] that included rare species, such as the Greater Horseshoe Bat, Geoffroy's Bat and the Pond Bat.[33][34]

The intercommunality of the Terre des Deux Caps and the authorities in nearly Landrethun set up a partnership to operate the site under the management of the existing museum of La Coupole near Saint-Omer. The director of the latter, historian Yves le Maner, designed the contents of a new museum that was constructed at a cost of €360,000.[5]

The site reopened to the public on 1 July 2010.[27] As well as presenting a history of the V-weapons and of the site, the museum enables visitors to see some of the tunnels and a mock-up of the HDP gun. The tunnels also house memorials to Joseph Kennedy, the other bomber crew members killed during raids on the site, and the forced labourers who lost their lives during construction.[29] In 2011, the museum had about 11,000 visitors, of whom 53% were French, 18% Belgian and 16% British.[35]

Air raids on the Mimoyecques site

| Date | Notes |

|---|---|

| 5 November 1943 | |

| 8 November 1943 | |

| 19 March 1944 | |

| 26 March 1944 | |

| 10 April 1944 | |

| 20 April 1944 | |

| 27 April 1944 | |

| 28 April 1944 | |

| 1 May 1944 | |

| 15 May 1944 | |

| 21 May 1944 | |

| 22 June 1944 | |

| 27 June 1944 | |

| 6 July 1944 | |

| 4 August 1944 | |

| 12 August 1944 | An Operation Anvil drone targeted on Mimoyecques detonated prematurely over the Blyth Estuary, killing the US Navy crew, Lieutenants Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. and Wilford J. Willy.[22] |

| 27 August 1944 |

See also

Notes

- ^ Literal translation "Fortress Pioneer Staff"

- ^ North entrance of railway tunnel: 50°51′32.15″N 1°45′49.75″E / 50.8589306°N 1.7638194°E. South exit: 50°51′9.66″N 1°45′32.62″E / 50.8526833°N 1.7590611°E

- ^ The branch line to Mimoyecques connected with the main line here: 50°51′33.63″N 1°45′52.01″E / 50.8593417°N 1.7644472°E

References

- ^ Zaloga, Johnson & Taylor 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Zaloga, Johnson & Taylor 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b Churchill, Winston (13 May 1945). "Forward, Till the Whole Task is Done". Churchill's War Time Speeches. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

... when all the preparations being made on the coasts of France and Holland could be examined in detail, in scientific detail, that we knew how grave had been the peril, not only from rockets and flying-bombs but from multiple long range artillery which was being prepared against London. Only just in time did the Allied armies blast the viper in his nest. Otherwise the autumn of 1944, to say nothing of 1945, might well have seen London as shattered as Berlin.

- ^ a b c Zaloga, Johnson & Taylor 2008, p. 14.

- ^ a b c "La forteresse de Mimoyecques devrait rouvrir le 1er juillet". La Voix du Nord (in French). 10 April 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e After the Battle 1974.

- ^ a b c Jones 1978, p. 463.

- ^ Zaloga, Johnson & Taylor 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Boelcke 1969, p. 290.

- ^ a b c Zaloga, Johnson & Taylor 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Sanders 1945, Technical details – Wizernes; Vol III, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Richely & Neve 1991 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRichelyNeve1991 (help).

- ^ a b Powys-Lybbe 1983, p. 210.

- ^ Bates 1994, p. 158.

- ^ a b Sanders 1945, p. 7.

- ^ a b Sanders 1945, p. 9.

- ^ a b Sanders 1945, p. 6.

- ^ Hölsken 1994, p. 178.

- ^ a b Henshall 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Sanders 1945, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Hinsley 1984, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d Bateman 2009, p. 78.

- ^ Henshall 2002, p. 176.

- ^ a b Sandys 1945.

- ^ Moench 1999, p. 93.

- ^ Dejonge & Le Maner 1999, p. 378.

- ^ a b "Le retour de pièces historiques à la forteresse de Mimoyecques". La Voix du Nord (in French). 15 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ P., M. (3 December 2008). "Forteresse V3 de Mimoyecques – La base secrète d'Hitler change de propriétaire" [Fortress V3 of Mimoyecques – Hitler's secret base changes hands]. La Semaine dans le Boulonnais (in French). Retrieved 25 June 2011.

Forty years after the destruction of the building, Marie-Madeleine Vasseur opened the site to the public as a museum and a mausoleum. By 1969, this farmer from Landrethun proposed to reopen the tunnel for growing mushrooms. ... Twenty-five years later, Marie-Madeilene Vasseur take a well-deserved retirement. (transl.)

- ^ a b Pallud 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Middlebrook 1991, p. 33.

- ^ "Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais (2011). "Évolution des populations de chauves-souris en hibernation entre 2000 et 2011 – Forteresse de Mimoyecques" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ "Un site d'hibernation de chauves-souris". La Voix du Nord (in French). 10 April 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais (2010). "Forteresse de Mimoyecques – Quand histoire et nature ne font qu'un" (in French). Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Conservatoire d'espaces naturels du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais (2012). "Les chiffres de la saison touristique à Mimoyecques". Rapport d'activités 2011 (PDF) (in French). p. 39.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Carter & Mueller 1991.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hammel 2009, pp. 204–5, 265, 268, 283, 287–8, 290, 299, 301, 353.

- ^ 11 Group ORB Appendix, 8 Nov 1944, TNA AIR 25/207.

- ^ a b "Campaign diary June 1944". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bateman 2009, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Hogg 1999, p. 48.

- ^ "Campaign diary August 1944". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Bateman, Alex (2009). No 617 'Dambusters' Sqn. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-429-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bates, Herbert Ernest (1994). Flying Bombs over England. Westerham: Froglets. ISBN 978-1-872337-04-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boelcke, Willi (1969). Deutschlands Rüstung im Zweiten Weltkrieg: Hitlers Konferenzen mit Albert Speer 1942–1945 (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carter, Kit C.; Mueller, Robert (1991). US Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology 1941–1945. Center for Air Force History. ISBN 978-1-4289-1543-5.

[citing:]Long-Range Rockets, in Plans file 8090-71; 9th AF Hist. Sec., CROSSBOW Operations Against Ski Sites, 5 December 1943-18 March 1944 (hereinafter cited as 9th AF CB Opns.); AAF Operations Against CROSSBOW and Ski Site Installations, in AC/AS, Plans file 8090-69.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dejonge, Étienne; Le Maner, Yves (1999). Le Nord-Pas-de-Calais dans la main allemande (in French). Lille: Le Voix du Nord. ISBN 978-2-84393-015-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammel, Eric (2009). Air War Europa: Chronology. Pacifica, CA: Pacifica Military History. ISBN 978-0-935553-65-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henshall, Philip (2002). Hitler's V-Weapon Sites. Stroud: Strutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2607-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hinsley, Francis H. (1984). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. Vol. 3. London: H.M.S.O. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-11-630935-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hogg, Ian V. (1999). German Secret Weapons of the Second World War. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-325-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hölsken, Dieter (1994). V-Missiles of the Third Reich, the V-1 and V-2. Monogram Aviation Publications.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Raymond Victor (1978). The Wizard War: British Scientific Intelligence, 1939–1945. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Middlebrook, Mary (1991). The Somme Battlefields: a comprehensive guide from Crécy to the two world wars. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-83083-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moench, John O. (1999). Marauder Men: an account of the Martin B-26 Marauder. Longwood, FL: Malia Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-877597-06-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pallud, Jean-Paul (2001). "The Secret Weapons: V3 and V4". After the Battle. 114: 2–29. ISSN 0306-154X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "The V-Weapons". After the Battle. 6: 23–24. 1974. ISSN 0306-154X.

- Powys-Lybbe, Ursula (1983). The eye of intelligence (1 ed.). London: Kimber. ISBN 978-0-7183-0468-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richely, Paul; Neve, André (September 1991). "Où sont les plaques cuirassées de Mimoyecques?" [Where are the armor plates of Mimoyecques?]. Bulletin d'information du CLHAM (in French). IV (11). Centre Liégeois d'Histoire et d'Archéologie Militaires. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

Three times we got a permit to visit the quarry. Our original intention was to photograph the Dom Bunker and the entrance to the gun tunnel. The unexpected and emotions were at the end of the road: a motley mass of steel plates. Our guide knew nothing about it and had no objection to photography of this bizarre material. Examination of the photographs confirmed our initial hypothesis : it could be the Mimoyecques plates. (transl.)

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Richely, Paul; Neve, André (September 1991). "Les péripéties du site d'Hydrequent-Rinxent" [The adventures of the Hydrequent-Rinxent site]. Bulletin d'information du CLHAM (in French). IV (11). Centre Liégeois d'Histoire et d'Archéologie Militaires. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

The OKW refuses to renounce to the HDP gun originally planned in Mimoyecques, it will be transferred to the site Rinxent which, in turn, finds a new role at the time of abandonment. The choice of Rinxent is based on several considerations: the absence of any bombing of the site that apparently has not worried the Allies, tunnels allowing to work within with virtually ensured safety, nature of the soil (marble), location. (transl.)

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sanders, Terence R. B. (1945). Investigation of the "Heavy" Crossbow installations in Northern France. Report by the Sanders Mission to the Chairman of the Crossbow Committee. London: War Office.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sandys, Duncan (19 March 1945). Report on 'Large' Crossbow Sites in Northern France. Memo C.O.S. (45) 177 (O). London: War Office.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zaloga, Steven J.; Johnson, Hugh; Taylor, Chris (2008). German V-Weapon Sites 1943–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-247-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Le retour de pièces historiques à la forteresse de Mimoyecques" [The return of the historic pieces to the Fortress of Mimoyecques]. La Voix du Nord (in French). 15 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Hautefeuille, Roland (1995). Constructions spéciales : histoire de la construction par l'"Organisation Todt", dans le Pas-de-Calais et la Cotentin, des neufs grands sites protégés pour le tir des V1, V2, V3, et la production d'oxygène liquide, (1943–1944) (in French) (2 ed.). Paris: Cerin. ISBN 2-9500899-0-9.

External links

- Fortress of Mimoyecques – museum website

- Template:Fr icon Une base pour bombarder Londres

- Template:Fr icon Chroniques Historiques – Les tunnels de Mimoyecques: la Base V3

- Template:Fr icon Forteresse de Mimoyecques – Quand histoire et nature ne font qu'un