Mnemonic

A mnemonic (/nəˈmɒnɪk/,[1] the first "m" is silent) device, or memory device, is any learning technique that aids information retention or retrieval (remembering) in the human memory. Mnemonics make use of elaborative encoding, retrieval cues, and imagery as specific tools to encode any given information in a way that allows for efficient storage and retrieval. Mnemonics aid original information in becoming associated with something more accessible or meaningful—which, in turn, provides better retention of the information. Commonly encountered mnemonics are often used for lists and in auditory form, such as short poems, acronyms, or memorable phrases, but mnemonics can also be used for other types of information and in visual or kinesthetic forms. Their use is based on the observation that the human mind more easily remembers spatial, personal, surprising, physical, sexual, humorous, or otherwise "relatable" information, rather than more abstract or impersonal forms of information.

The word "mnemonic" is derived from the Ancient Greek word μνημονικός (mnēmonikos), meaning "of memory, or relating to memory"[2] and is related to Mnemosyne ("remembrance"), the name of the goddess of memory in Greek mythology. Both of these words are derived from μνήμη (mnēmē), "remembrance, memory".[3] Mnemonics in antiquity were most often considered in the context of what is today known as the art of memory.

Ancient Greeks and Romans distinguished between two types of memory: the "natural" memory and the "artificial" memory. The former is inborn, and is the one that everyone uses instinctively. The latter in contrast has to be trained and developed through the learning and practice of a variety of mnemonic techniques.

Mnemonic systems are techniques or strategies consciously used to improve memory. They help use information already stored in long-term memory to make memorisation an easier task.[4]

History

The general name of mnemonics, or memoria technica, was the name applied to devices for aiding the memory, to enable the mind to reproduce a relatively unfamiliar idea, and especially a series of dissociated ideas, by connecting it, or them, in some artificial whole, the parts of which are mutually suggestive.[5] Mnemonic devices were much cultivated by Greek sophists and philosophers and are frequently referred to by Plato and Aristotle. In later times the poet Simonides was credited for development of these techniques, perhaps for no reason other than that the power of his memory was famous. Cicero, who attaches considerable importance to the art, but more to the principle of order as the best help to memory, speaks of Carneades (perhaps Charmades) of Athens and Metrodorus of Scepsis as distinguished examples of people who used well-ordered images to aid the memory. The Romans valued such helps in order to support facility in public speaking.[6]

The Greek and the Roman system of mnemonics was founded on the use of mental places and signs or pictures, known as "topical" mnemonics. The most usual method was to choose a large house, of which the apartments, walls, windows, statues, furniture, etc., were each associated with certain names, phrases, events or ideas, by means of symbolic pictures. To recall these, an individual had only to search over the apartments of the house until discovering the places where images had been placed by the imagination.[citation needed]

In accordance with said system, if it were desired to fix a historic date in memory, it was localised in an imaginary town divided into a certain number of districts, each of with ten houses, each house with ten rooms, and each room with a hundred quadrates or memory-places, partly on the floor, partly on the four walls, partly on the roof. Therefore, if it were desired to fix in the memory the date of the invention of printing (1436), an imaginary book, or some other symbol of printing, would be placed in the thirty-sixth quadrate or memory-place of the fourth room of the first house of the historic district of the town.[citation needed] Except that the rules of mnemonics are referred to by Martianus Capella, nothing further is known regarding the practice until the 13th century.[5]

Among the voluminous writings of Roger Bacon is a tractate De arte memorativa. Ramon Llull devoted special attention to mnemonics in connection with his ars generalis. The first important modification of the method of the Romans was that invented by the German poet Konrad Celtes, who, in his Epitoma in utramque Ciceronis rhetoricam cum arte memorativa nova (1492), used letters of the alphabet for associations, rather than places. About the end of the 15th century, Petrus de Ravenna (b. 1448) provoked such astonishment in Italy by his mnemonic feats that he was believed by many to be a necromancer. His Phoenix artis memoriae (Venice, 1491, 4 vols.) went through as many as nine editions, the seventh being published at Cologne in 1608.

About the end of the 16th century, Lambert Schenkel (Gazophylacium, 1610), who taught mnemonics in France, Italy and Germany, similarly surprised people with his memory. He was denounced as a sorcerer by the University of Louvain, but in 1593 he published his tractate De memoria at Douai with the sanction of that celebrated theological faculty. The most complete account of his system is given in two works by his pupil Martin Sommer, published in Venice in 1619. In 1618 John Willis (d. 1628?) published Mnemonica; sive ars reminiscendi,[7] containing a clear statement of the principles of topical or local mnemonics. Giordano Bruno included a memoria technica in his treatise De umbris idearum, as part of his study of the ars generalis of Llull. Other writers of this period are the Florentine Publicius (1482); Johannes Romberch (1533); Hieronimo Morafiot, Ars memoriae (1602);and B. Porta, Ars reminiscendi (1602).[5]

In 1648 Stanislaus Mink von Wennsshein revealed what he called the "most fertile secret" in mnemonics — using consonants for figures, thus expressing numbers by words (vowels being added as required), in order to create associations more readily remembered. The philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz adopted an alphabet very similar to that of Wennsshein for his scheme of a form of writing common to all languages.

Wennsshein's method was adopted with slight changes afterward by the majority of subsequent "original" systems. It was modified and supplemented by Richard Grey (1694-1771), a priest who published a Memoria technica in 1730. The principal part of Grey's method is briefly this:

To remember anything in history, chronology, geography, etc., a word is formed, the beginning whereof, being the first syllable or syllables of the thing sought, does, by frequent repetition, of course draw after it the latter part, which is so contrived as to give the answer. Thus, in history, the Deluge happened in the year before Christ two thousand three hundred forty-eight; this is signified by the word Del-etok, Del standing for Deluge and etok for 2348.[5]

(His method is comparable to the Hebrew system by which letters also stand for numerals, and therefore words for dates.)

To assist in retaining the mnemonical words in the memory, they were formed into memorial lines. Such strange words in difficult hexameter scansion, are by no means easy to memorise. The vowel or consonant, which Grey connected with a particular figure, was chosen arbitrarily.

A later modification was made in 1806 Gregor von Feinaigle, a German monk from Salem near Constance. While living and working in Paris, he expounded a system of mnemonics in which (as in Wennsshein) the numerical figures are represented by letters chosen due to some similarity to the figure or an accidental connection with it. This alphabet was supplemented by a complicated system of localities and signs. Feinaigle, who apparently did not publish any written documentation of this method, travelled to England in 1811. The following year one of his pupils published The New Art of Memory (1812), giving Feinaigle's system. In addition, it contains valuable historical material about previous systems.

Other mnemonists later published simplified forms, as the more complicated menemonics were generally abandoned. Methods founded chiefly on the so-called laws of association (cf. Mental association) were taught with some success in Germany.[8]

Types

- 1. Music mnemonics

- Songs and jingles can be used as a mnemonic. A common example is how children remember the alphabet by singing the ABC's.

- 2. Name mnemonics (acronym)

- The first letter of each word is combined into a new word. For example: VIBGYOR (or ROY G BIV) for the colours of the rainbow or HOMES for the Great Lakes.

- 3. Expression or word mnemonics

- The first letter of each word is combined to form a phrase or sentence -- e.g. "Richard of York gave battle in vain" for the colours of the rainbow.

- 4. Model mnemonics

- A model is used to help recall information.[clarification needed]

- 5. Ode mnemonics

- The information is placed into a poem or doggerel, -- e.g. 'Note socer, gener, liberi, and Liber god of revelry, like puer these retain the 'e (most Latin nouns of the second declension ending in -er drop the -e in all of the oblique cases except the vocative, these are the exceptions).

- 6. Note organization mnemonics

- The method of note organization can be used as a memorization technique.[clarification needed][clarification needed]

- 7. Image mnemonics

- The information is constructed into a picture -- e.g. the German weak declension can be remembered as five '-e's', looking rather like the state of Oklahoma in America, in a sea of '-en's'.

- 8. Connection mnemonics

- New knowledge is connected to knowledge already known.

- 9. Spelling mnemonics

- An example is "i before e except after c or when sounding like a in neighbor and weigh".[9]

Applications and examples

A wide range of mnemonics are used for several purposes. The most commonly used mnemonics are those for lists, numerical sequences, foreign-language acquisition, and medical treatment for patients with memory deficits.

For lists

A common mnemonic for remembering lists is to create an easily remembered acronym, or, taking each of the initial letters of the list members, create a memorable phrase in which the words with the same acronym as the material. Mnemonic techniques can be applied to most memorisation of novel materials.

Some common examples for first letter mnemonics:

- "Memory Needs Every Method Of Nurturing Its Capacity" is a mnemonic for spelling 'mnemonic.'

- To memorize the metric prefixes after Giga(byte), think of the candy, and this mnemonic. Tangiest PEZ? Yellow! TPEZY. Tera, Peta, Exa, Zetta, Yotta(byte).

- "Maybe Not Every Mnemonic Oozes Nuisance Intensely Concentrated" is perhaps a less common mnemonic for spelling 'mnemonic', but it benefits from being a bit humorous and memorable.

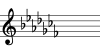

- The order of sharps in key signature notation is F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯ and B♯, giving the mnemonic "Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle". The order of flats is the reverse: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭ and F♭ ("Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles' Father").[10]

- To memorise the colours of the rainbow: the phrase "Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain" - each of the initial letters matches the colours of the rainbow in order (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet). Other examples are the phrase "Run over your granny because it's violent" or the imaginary name "Roy G. Biv".

- To memorise the North American Great Lakes: the acronym HOMES - matching the letters of the five lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior) [11]

- To memorise colour codes as they are used in electronics: the phrase "Bill Brown Realised Only Yesterday Good Boys Value Good Work" represents in order the 10 colours and their numerical order: black (0), brown (1), red (2), orange (3), yellow (4), green (5), blue (6), violet or purple (7), grey (8), and white (9).[12]

- To memorise chemical reactions, such as redox reactions, where it is common to mix up oxidation and reduction, the short phrase "LEO (Lose Electron Oxidation) the lion says GER (Gain Electron Reduction)" or "Oil Rig" can be used - which is an acronym for "Oxidation is losing, Reduction is gaining".[13] John "Doc" Walters, who taught chemistry and physics at Browne & Nichols School in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the 1950s and 1960s, taught his students to use for this purpose the acronym RACOLA: Reduction is Addition of electrons and occurs at the Cathode; Oxidation is Loss of electrons and occurs at the Anode.

- To memorise the names of the planets and Pluto, use the planetary mnemonic: "My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nachos" or "My Very Easy Method Just Speeds Up Naming Planets" or "My Very Educated Mother Just Showed Us Nine Planets"- where each of the initial letters matches the name of the planets in our solar system (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, [Pluto]).[14]

- To memorise the sequence of stellar classification: "Oh, Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me" - where O, B, A, F, G, K, M are categories of stars.[15]

For numerical sequences and mathematical operations

Mnemonic phrases or poems can be used to encode numeric sequences by various methods, one common one is to create a new phrase in which the number of letters in each word represents the according digit of pi. For example, the first 15 digits of the mathematical constant pi (3.14159265358979) can be encoded as "Now I need a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics"; "Now", having 3 letters, represents the first number, 3. Piphilology is the practice dedicated to creating mnemonics for pi.

Another is used for "calculating" the multiples of 9 up to 9 × 10 using one's fingers. Begin by holding out both hands with all fingers stretched out. Now count left to right the number of fingers that indicates the multiple. For example, to figure 9 × 4, count four fingers from the left, ending at your left-hand index finger. Bend this finger down and count the remaining fingers. Fingers to the left of the bent finger represent tens, fingers to the right are ones. There are three fingers to the left and six to the right, which indicates 9 × 4 = 36. This works for 9 × 1 up through 9 × 10.

For remembering the rules in adding and multiplying two signed numbers, Balbuena and Buayan (2015) made the letter strategies LAUS (like signs, add; unlike signs, subtract) and LPUN (like signs, positive; unlike signs, negative), respectively.[16]

For foreign-language acquisition

Mnemonics may be helpful in learning foreign languages, for example by transposing difficult foreign words with words in a language the learner knows already, also called "cognates" which are very common in the Spanish language. A useful such technique is to find linkwords, words that have the same pronunciation in a known language as the target word, and associate them visually or auditorially with the target word.

For example, in trying to assist the learner to remember ohel (אוהל), the Hebrew word for tent, the linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann proposes the memorable sentence "Oh hell, there's a raccoon in my tent"[17]. The memorable sentence "There's a fork in Ma’s leg" helps the learner remember that the Hebrew word for fork is mazleg (מזלג).[18], Similarly, to remember the Hebrew word bayit (בית), meaning house, one can use the sentence "that's a lovely house, I'd like to buy it."[18] The linguist Michel Thomas taught students to remember that estar is the Spanish word for to be by using the phrase "to be a star".[19]

Another Spanish example is by using the mnemonic "Vin Diesel Has Ten Weapons" to teach irregular command verbs in the you form. Spanish verb forms and tenses are regularly seen as the hardest part of learning the language. With a high number of verb tenses, and many verb forms that are not found in English, Spanish verbs can be hard to remember and then conjugate. The use of mnemonics has been proven to help students better learn foreign languages, and this holds true for Spanish verbs. A particularly hard verb tense to remember is command verbs. Command verbs in Spanish are conjugated differently depending on who the command is being given to. The phrase, when pronounced with a Spanish accent, is used to remember "Ven Di Sal Haz Ten Ve Pon Sé", all of the irregular Spanish command verbs in the you form. This mnemonic helps students attempting to memorize different verb tenses.[20] Another technique is for learners of gendered languages to associate their mental images of words with a colour that matches the gender in the target language. An example here is to remember the Spanish word for "foot," pie, [pee-ay] with the image of a foot stepping on a pie, which then spills blue filling (blue representing the male gender of the noun in this example).

For French verbs which use etre as a participle: MRS VANDERTRAMP: monter, retourner, sortir, venir, arriver, naître, entrer, rester, tomber, rentrer, aller, mourir. .

Masculine countries in French (le): "Neither can a breeze make a sane Japanese chilly in the USA." Netherlands, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Senegal, Japan, Chile & (les) USA.

For patients with memory deficits

Mnemonics can be used in aiding patients with memory deficits that could be caused by head injuries, strokes, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and other neurological conditions.

In a study conducted by Doornhein and De Haan, the patients were treated with six different memory strategies including the mnemonics technique. The results concluded that there were significant improvements on the immediate and delayed subtest of the RBMT, delayed recall on the Appointments test, and relatives rating on the MAC from the patients that received mnemonics treatment. However, in the case of stroke patients, the results did not reach statistical significance.[21]

Effectiveness

Academic study of the use of mnemonics has shown their effectiveness. In one such experiment, subjects of different ages who applied mnemonic techniques to learn novel vocabulary outperformed control groups that applied contextual learning and free-learning styles.[22]

Mnemonics vary in effectiveness for several groups ranging from young children to the elderly. Mnemonic learning strategies require time and resources by educators to develop creative and effective devices. The most simple and creative mnemonic devices usually are the most effective for teaching. In the classroom, mnemonic devices must be used at the appropriate time in the instructional sequence to achieve their maximum effectiveness.[23]

Mnemonics were seen to be more effective for groups of people who struggled with or had weak long-term memory, like the elderly. Five years after a mnemonic training study, a research team followed-up 112 community-dwelling older adults, 60 years of age and over. Delayed recall of a word list was assessed prior to, and immediately following mnemonic training, and at the 5-year follow-up. Overall, there was no significant difference between word recall prior to training and that exhibited at follow-up. However, pre-training performance gains scores in performance immediately post-training and use of the mnemonic predicted performance at follow-up. Individuals who self-reported using the mnemonic exhibited the highest performance overall, with scores significantly higher than at pre-training. The findings suggest that mnemonic training has long-term benefits for some older adults, particularly those who continue to employ the mnemonic.[24]

This contrasts with a study from surveys of medical students that approximately only 20% frequently used mnemonic acronyms.[25]

In humans, the process of aging particularly affects the medial temporal lobe and hippocampus, in which the episodic memory is synthesized. The episodic memory stores information about items, objects, or features with spatiotemporal contexts. Since mnemonics aid better in remembering spatial or physical information rather than more abstract forms, its effect may vary according to a subject's age and how well the subject's medial temporal lobe and hippocampus function.

This could be further explained by one recent study which indicates a general deficit in the memory for spatial locations in aged adults (mean age 69.7 with standard deviation of 7.4 years) compared to young adults (mean age 21.7 with standard deviation of 4.2 years). At first, the difference in target recognition was not significant.

The researchers then divided the aged adults into two groups, aged unimpaired and aged impaired, according to a neuropsychological testing. With the aged groups split, there was an apparent deficit in target recognition in aged impaired adults compared to both young adults and aged unimpaired adults. This further supports the varying effectiveness of mnemonics in different age groups.[26]

Moreover, a different research was done previously with the same notion, which presented with similar results to that of Reagh et al. in verbal mnemonics discrimination task.[27]

Studies (notably "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two") have suggested that the short-term memory of adult humans can hold only a limited number of items; grouping items into larger chunks such as in a mnemonic might be part of what permits the retention of a larger total amount of information in short-term memory, which in turn can aid in the creation of long-term memories.

See also

- List of mnemonics

- List of visual mnemonics

- Memorization

- Memory sport

- Method of loci

- Mnemonic dominic system

- Mnemonic goroawase system

- Mnemonic link system

- Mnemonic major system

- Mnemonic peg system

- Mnemonics in assembler programming languages

- Mnemonic effect (advertising)

References

- ^ Soanes, Catherine; Stevenson, Angus; Hawker, Sara, eds. (29 March 2006). Concise Oxford English Dictionary (Computer Software): entry "mnemonic" (11th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ μνημονικός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ μνήμη, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Carlson, Neil; et al. Psychology the Science of Behavior. Pearson Canada, United States of America. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- ^ a b c d This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mnemonics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 629–630. - and respective bibliography for this specific section.

- ^ The method used is described by the author of Rhet ad Heren. iii. 16-24; see also Quintilian (Inst. Or. xi. 2), whose account is, however, obscure. In his time the art had almost ceased to be practiced.

- ^ English version by Leonard Sowersby, 1661; extracts in Gregor von Feinaigle's New Art of Memory, 3rd ed., 1813.

- ^ A simplified form of Feinaigle's method was published by Aimé Paris (Principes et applications diverses de la mnémonique, 7th ed., Paris, 1834). The use of symbolic pictures was revived in connection with the latter by Antoni Jaźwińsky of Poland. His system was published by the Polish general J. Bem, under the title Exposé général de la méthode mnémonique polonaise, perfectionnée à Paris (Paris, 1839). Various other modifications of the systems were advocated by subsequent mnemonists right through the 19th century. More complicated systems were proposed in the 20th century, such as the Keesing Memory System, the System of Memory and Mental Training, and the Pelman memory system.

- ^ Types of mnemonics

- ^ Educational Plans in Music Teaching, The Quarterly Music Review, Vol. 1, 1885

- ^ Great Lakes Mnemonic

- ^ Gambhir, R.S. (1993). Foundations Of Physics. Vol. 2. New Age International. p. 49. ISBN 81-224-0523-1.

- ^ Glynn, Shawn; et al. (2003). Mnemonic Methods. The Science Teacher. pp. 52–55.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on Planets". Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mnemonic Oh, Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me! in Astronomy". Mnemonic Devices Memory Tools.

- ^ http://apjeas.apjmr.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/APJEAS-2.3-Revised-Mnemonics-and-Gaming1.pdf

- ^ http://www.professorzuckermann.com/anglo-hebraic-lexical-mnemonics

- ^ a b Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2011). "Mnemonics in Second Language Acquisition". Word Ways: The Journal of Recreational Linguistics. 44 (4): 302–309.

- ^ "How to Master a Foreign Language". buildyourmemory.com. Archived from the original on 2015-03-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Irregular Spanish Imperatives Made Easy by Vin Diesel". AlwaysSpanish.com. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ das Nair, RD; Lincoln, NB (8 July 2008). "Cognitive rehabilitation for memory deficits following stroke" (PDF). The Cochrane Collaboration. JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.: 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002293.pub2.

- ^ Levin, Joel R.; Levin, Mary E.; Glasman, Lynette D.; Nordwall, Margaret B. (April 1992). "Mnemonic vocabulary instruction: Additional effectiveness evidence". Contemporary Educational Psychology. 17 (2): 156–174. doi:10.1016/0361-476x(92)90056-5.

- ^ Seay, Sharon S.; McAlum, Harry G. (May 2010). "The use/application of mnemonics as a pedagogical tool in auditing" (PDF). Academy of Educational Leadership Journal. 14 (22): 33–47.

- ^ O’Hara, Ruth; Brooks, John O.; Friedman, Leah; Schröder, Carmen M.; Morgan, Kevin S.; Kraemer, Helena C. (October 2007). "Long-term effects of mnemonic training in community-dwelling older adults". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 41 (7): 585–590. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.04.010.

- ^ Brotle, Charles D. (2011). The role of mnemonic acronyms in clinical emergency medicine: A grounded theory study (EdD thesis). ProQuest.

- ^ Reagh, Zachariah M.; Roberts, Jared M.; Ly, Maria; DiProspero, Natalie; Murray, Elizabeth; Yassa, Michael A. (March 2014). "Spatial discrimination deficits as a function of mnemonic interference in aged adults with and without memory impairment". Hippocampus. 24 (3): 303–314. doi:10.1002/hipo.22224. PMC 3968903. PMID 24167060.

- ^ Ly, Maria; Murray, Elizabeth; Yassa, Michael A. (June 2013). "Perceptual versus conceptual interference and pattern separation of verbal stimuli in young and older adults". Hippocampus. 23 (6): 425–430. doi:10.1002/hipo.22110. PMC 3968906. PMID 23505005.