Ethiopians

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (July 2013) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 107 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 460,000[2] | |

| 130,000[3] | |

| 110,000[2] | |

| 90,000[2] | |

| 30,000[2] | |

| 20,000[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Amharic, Oromo, Somali, Tigrinya, Wolaytta, Gurage, Sidamo | |

| Religion | |

| Christian 62.8% (Ethiopian Orthodox 43.5%, Protestant 19.3% (e.g. P'ent'ay), Catholic 0.9%), Muslim 33.9%, Traditional 2.6%. Jewish 1%,[5] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Oromo 34.5% Amhara 26.9% Somali 6.2% Tigraway 6.1% Sidama 4% Gurage 2.5% Wolayta 2.3% Hadiya 1.7% Afar 1.7%[6] (see Ethnicity) | |

Ethiopia's population is highly diverse. Most of its people speak a Semitic or Cushitic language. The Oromo, Amhara, Somali and Tigrayans make up more than three-quarters (75%) of the population, but there are more than 80 different ethnic groups within Ethiopia. Some of these have as few as 10,000 members. English is the most widely spoken foreign language and is taught in all secondary schools. Amharic was the language of primary school instruction but has been replaced in many areas by local languages such as Oromifa, Somali and Tigrinya.

Ethnicity

- Oromo 34.6%[7]

- Amhara 27.1%[7]

- Somali 6.1%

- Tigray 6.1%

- Sidama 4%

- Gurage 2.5%

- Welayta 2.3%

- Hadiya 1.9%

- Afar 1.7%

- Qemant 1.0% [6]

Languages

According to the 2007 Ethiopian census, the largest first languages are: Oromo 24,929,567 speakers or 33.8% of the total population; Amharic 21,631,370 or 29.1% (federal working language); Somali 4,609,274 or 6.2%; Tigrinya 4,324,476 or 5.86%; Sidamo 4,981,471 or 4%; Wolaytta 1,627,784 or 2.2%; Gurage 1,481,783 or 2.01%; and Afar 1,281,278 or 1.74%.[6][8] [7] Widely-spoken foreign languages include Arabic (official), English (official; major foreign language taught in schools), and Italian (spoken by European minorities).[6]

Religion

According to the CIA Factbook the religious demography of Ethiopia is as follows; Ethiopian Orthodox 43.5%, Muslim 31.9%, Protestant 18.5%, traditional 2.7%, Catholic 0.4%, and other 0.5%.[7]

Diaspora

The largest diaspora community is found in the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau,[9] 250,000, Ethiopian immigrants lived in the United States as of 2008. An additional 30,000 U.S.-born citizens reported Ethiopian ancestry.[10] According to Aaron Matteo Terrazas, "if the descendants of Ethiopian-born migrants (the second generation and up) are included, the estimates range upwards of 460,000 in the United States (of which approximately 350,000 are in Washington, DC; 96,000 in Los Angeles; and 10,000 in New York)."[2]

A large Ethiopian community is also found in Israel, where Ethiopians make up almost 1.9% of the population; almost the entire community are members of the Beta Israel community. There are also large number of Ethiopian emigrants in Saudi Arabia, Italy, Lebanon, United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden and Australia.

Genetic studies

Autosomal DNA

Tishkoff et al. (2009) identified fourteen ancestral population clusters which correlate with self-described ethnicity and shared cultural and/or linguistic properties in Africa in what was the largest autosomal study of the continent to date.[failed verification][11] The Burji, Konso and Beta Israel were sampled from Ethiopia. The Afroasiatic speaking Ethiopians sampled were cumulatively (Fig.5B) found to belong to: 71% in the "Cushitic" cluster, 6% in the "Saharan/Dogon" cluster, 5% in the "Niger Kordofanian" cluster, 3% each in the "Nilo-Saharan" and "Chadic Saharan" cluster, while the balance (12%) of their assignment was distributed among the remnant (9) Associated Ancestral Clusters (AAC's) found in Sub-Saharan Africa.[12] The "Cushitic" cluster was also deemed "closest to the non-African AACs, consistent with an East African migration of modern humans out of Africa or a back-migration of non-Africans into Saharan and Eastern Africa."[13]

Wilson et al. (2001), an autosomal DNA study based on cluster analysis that looked at a combined sample of Amhara and Oromo examining a single enzyme variants: drug metabolizing enzyme (DME) loci, found that 62% of Ethiopeans fall into the same cluster of Ashkenazi Jews, Norwegians and Armenians based on that gene. Only 24% of Ethiopians cluster with Bantus and Afro-Caribbeans, 8% with Papua New Guineans, and 6% with Chinese.[14]

Paternal lineages

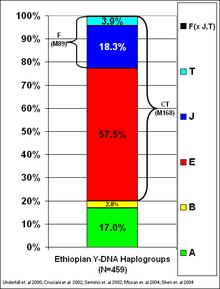

A composite look at most YDNA studies done so far[16][17][15][18][19] reveals that,out of a total of 459 males sampled from Ethiopia, approximately 58% of Y-chromosome haplotypes were found to belong to Haplogroup E, of which 71% (41% of total) were characterized by one of its further downstream sub lineage known as E1b1b, while the remainder were mostly characterized by Haplogroup E1b1(x E1b1b,E1b1a), and to a lesser extent Haplogroup E2. With respect to E1b1b, some studies have found that it exists at its highest level among the Oromo, where it represented 62.8% of the haplotypes, while it was found at 35.4% among the Amhara,[17] other studies however have found an almost equal representation of Haplogroup E1b1b at approximately 57% in both the Oromo and the Amhara.[20] The haplogroup (as its predecessor E1b1) is thought to have originated in Ethiopia or elsewhere in the Horn of Africa. About one half of E1b1b found in Ethiopia is further characterized by E1b1b1a (M78), which arose later in north-eastern Africa and then back-migrated to eastern Africa.[21]

Haplogroup J has been found at a frequency of approximately 18% in Ethiopians, with a higher prevalence among the Amhara, where it has been found to exist at levels as high as 35%, of which about 94% (17% of total) is of the type J1, while 6% (1% of total) is of J2 type.[22] On the other hand, 26% of the individuals sampled in the Arsi control portion of Moran et al. (2004) were found to belong to Haplogroup J.[18]

Another fairly prevalent lineage in Ethiopia belongs to Haplogroup A, occurring at a frequency of about 17% within Ethiopia, it is almost all characterized by its downstream sub lineage of A3b2 (M13). Restricted to Africa, and mostly found along the Rift Valley from Ethiopia to Cape Town, Haplogroup A represents the deepest branch in the Human Y- Chromosome phylogeny.[23]

Finally, Haplogroup T at approximately 4% and Haplogroup B at approximately 3%, make up the remainder of the Y-DNA Haplogroups found within Ethiopia.

Maternal lineages

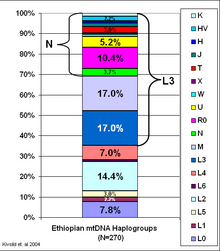

The maternal ancestry of Ethiopians is similarly diverse. About half (52.2%) of Ethiopians belongs to mtdna Haplogroups L0, L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, or L6. These haplogroups are generally confined to the African continent. They also originated either in Ethiopia or very near. The other portion of the population belong to Haplogroup N (31%) and Haplogroup M1 (17%).[24] There is controversy surrounding their origins as either native or a possible ancient back migration into Ethiopia from Asia.

Passarino et al. (1998) suggested that:

Caucasoid gene flow into the Ethiopian gene pool occurred predominantly through males. Conversely, the Niger–Congo contribution to the Ethiopian population occurred mainly through females.[25]

While there is debate among the scientific community of what exactly constitutes "Caucasoid gene flow",[26][27] the same study further stated:

Indeed, Ethiopians do not seem to result only from a simple combination of proto-Niger–Congo and Middle Eastern genes. Their African component cannot be completely explained by that of present-day Niger–Congo speakers, and it is quite different from that of the Khoisan. Thus, a portion of the current Ethiopian gene pool may be the product of in situ differentiation from an ancestral gene pool."[25]

Scott et al. (2005) similarly observed that the Ethiopian population is almost equally divided between individuals that carry Eurasian maternal lineages, and those that belong to African clades. They describe the presence of Eurasian clades in the country as sequences that "are thought to be found in high numbers in Ethiopia either as a result of substantial gene flow into Ethiopia from Eurasia (Chen et al., 2000; Richards et al., 2003), or as a result of having undergone several branching events in demic diffusion, acting as founder lineages for non-African populations". The researchers further found no association between regional origin of subjects or language family (Semitic/Cushitic) and their mitochondrial type:

The haplogroup distribution amongst all subjects (athletes and controls) from different geographical regions of Ethiopia is displayed in Table 3. As can be seen graphically in Fig. 3, the mtDNA haplogroup distribution of each region is similar, with all regions displaying similar proportions of African 'L' haplogroups (Addis Ababa: 59%, Arsi: 50%, Shewa: 44%, Other: 57%). No association was found between regional origin of subjects and their mitochondrial type (v2=8.5, 15 df, P=0.9). Similarly, the mtDNA haplogroup distribution of subjects (athletes and controls) speaking languages from each family is shown in Table 3. Again there was no association between language family and mitochondrial type (v2=5.4, 5 df, P=0.37). As can be seen in Fig. 4, the haplogroup distributions of each language family are again very similar.[28]

In addition, Musilová et al. (2011) observed significant maternal ties between its Ethiopian and other Horn African samples with its Western Asian samples; particularly in terms of the HV1b mtDNA haplogroup. The authors noted:

"Detailed phylogeography of HV1 sequences shows that more recent demographic upheavals likely contributed to their spread from West Arabia to East Africa, a finding concordant with archaeological records suggesting intensive maritime trade in the Red Sea from the sixth millennium BC onwards."[29]

According to Černý et al. (2008), many Ethiopians also share specific maternal lineages with areas in Yemen and other parts of Northeast Africa. The authors indicate that:

"The most frequent haplotype in west coastal Yemen is 16126–16362, which is found not only in the Ethiopian highlands but also in Somalia, lower Egypt and at especially high frequency in the Nubians. The Tihama share some West Eurasian haplotypes with Africans, e.g. J and K with Ethiopians, Somali and Egyptians."[30]

Origins

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (May 2012) |

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (September 2009) |

Ethiopia and Sudan are largely agreed upon by most linguists as the Afro-Asiatic Urheimat. More recent linguistic studies as to the origin of the Ethiosemitic languages seem to support [citation needed]the DNA findings of immigration from the Arabian Peninsula with a recent study using Bayesian computational phylogenetic techniques finding that "contemporary Ethiosemitic languages of Africa reflect a single introduction of early Ethiosemitic from southern Arabia approximately 2,800 years ago", and that this single introduction of Ethiosemitic underwent "Rapid Diversification" within Ethiopia.[31] The study also went further to state, "Thus, we propose that the current distribution of Ethiosemitic reflects a process of language diffusion through existing African populations with little gene flow from the Arabian Peninsula (i.e. a language shift)."[31]

There are many theories regarding the beginning of the Ethiopian civilisation. One theory, which is more widely accepted today locates its origins in Punt,[32] while acknowledging the influence of the Sabeans on the opposite side of the Red Sea.[33] At a later period, Ethiopian civilisation was exposed to Judaic influence, of which the best-known examples are the Qemant and Ethiopian Jews (or Beta Israel) ethnic groups, but Judaic customs, terminology, and beliefs can be found amongst the dominant culture of the Amhara and Tigrinya.[34] Indian alphabets have been claimed as the example used to create the vowel system of the Ge'ez abugida.[35]

History

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (May 2012) |

Around the 7th century BC, the kingdom of D'mt (D'amt) was established in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its capital at Yeha in northern Ethiopia. After the fall of D`mt in the 5th century BC, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms, until the rise of one of these kingdoms, the Aksumite Kingdom, ancestor of medieval and modern Ethiopia, during the first century BC, was able to reunite the area.[36] They established bases on the northern highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau and from there expanded southward. The Persian religious figure Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his time.[37] It was in the early 4th century AD that a Syro-Greek castaway, Frumentius, was taken to the court and eventually converted King Ezana to Christianity, thereby making it the official state religion.[38] For this accomplishment, he received the title "Abba Selama" ("Father of peace"). At various times, including a period in the 6th century, Axum controlled most of modern-day Yemen and some of southern Saudi Arabia just across the Red Sea, as well as controlling northern Sudan, northern Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti.[39]

The line of rulers descended from the Axumite kings was broken several times: first by the Jewish or pagan Queen Gudit around 950[40] or 850.[41] It was then interrupted by the Zagwe dynasty; it was during this dynasty that the famous rock-hewn churches of Lalibela were carved under King Lalibela, allowed by a long period of peace and stability.[42] Around 1270, the Solomonic dynasty came to control Ethiopia, claiming descent from the kings of Axum. They called themselves Neguse Negest ("King of Kings," or Emperor), basing their claims on their direct descent from Solomon and the queen of Sheba.[43]

During the reign of Emperor Yeshaq, Ethiopia made its first successful diplomatic contact with a European country since Aksumite times, sending two emissaries to Alfons V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries that failed to complete the trip to Ethiopia.[44] The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[45] This proved to be an important development, for when the Empire was subjected to the attacks of the Adal General and Imam, Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (called "Grañ", or "the Left-handed"), Portugal responded to Lebna Dengel's plea for help with an army of 400 men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[46] However, when Emperor Susenyos converted to Roman Catholicism in 1624, years of revolt and civil unrest followed resulting in thousands of deaths.[47] The Jesuit missionaries had offended the Orthodox faith of the local Ethiopians, and on 25 June 1632 Susenyos' son, Emperor Fasilides, declared the state religion to again be Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and expelled the Jesuit missionaries and other Europeans.[48][49]

All of this contributed to Ethiopia's isolation from 1755 to 1855, called the Zemene Mesafint or "Age of Princes." The Emperors became figureheads, controlled by warlords like Ras Mikael Sehul of Tigray, and later by the Oromo Yejju dynasty.[50] Ethiopian isolationism ended following a British mission that concluded an alliance between the two nations; however, it was not until the reign of Emperor Tewodros II, who began modernizing Ethiopia and recentralising power in the Emperor, that Ethiopia began to take part in world affairs once again.

The 1880s were marked by the Scramble for Africa and modernisation in Ethiopia, when the Italians began to vie with the British for influence in bordering regions. Asseb, a port near the southern entrance of the Red Sea, was bought from the local Afar sultan, vassal to the Ethiopian Emperor, in March 1870 by an Italian company, which by 1890 led to the Italian colony of Eritrea. Conflicts between the two countries resulted in the Battle of Adowa in 1896, whereupon the Ethiopians defeated the Italian forces and remained independent, under the rule of Menelik II. Italy and Ethiopia signed a provisional treaty of peace on 26 October 1896.

The early 20th century was marked by the reign of Emperor Lej Iyasu,[51] who undertook the rapid modernisation of Ethiopia — interrupted only by the brief Italian occupation (1936–1941).[52] British and patriot Ethiopian troops liberated the Ethiopian homeland in 1941, which was followed by sovereignty on 31 January 1941 and British recognition of full sovereignty (i.e. without any special British privileges) with the signing of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in December 1944.[53]

Footnotes

- ^ "Ethiopia – People Groups". Joshua Project. U.S. Center for World Mission. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Terrazas, Aaron Matteo (June 2007). "Beyond Regional Circularity: The Emergence of an Ethiopian Diaspora". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics: The Ethiopian Community in Israel

- ^ "Ethiopian London". BBC. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ^ Berhanu Abegaz, "Ethiopia: A Model Nation of Minorities" (accessed 6 April 2006)

- ^ a b c d "Ethiopia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ a b c d "Ethiopia People 2017". theodora.com. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "Statistical Tables for the 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Country Level". Central Statistical Agency. 2007. pp. 91–92. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- ^ "Ethiopia 5th largest source of Black Immigrants in America". Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Giorgis, Tedla W. "Potential into Practice: The Ethiopian Diaspora Volunteer Program". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ Out of Africa: Penn Geneticist Publishes Largest-Ever Study on African Genetics Revealing Origins, Migration.

- ^ Tishkoff, SA; Reed, FA; Friedlaender, FR; Ehret, C; Ranciaro, A; Froment, A; Hirbo, JB; Awomoyi, AA; Bodo, JM (May 2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–1044. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

- ^ Tishkoff, SA; Reed, FA; Friedlaender, FR; Ehret, C; Ranciaro, A; Froment, A; Hirbo, JB; Awomoyi, AA; Bodo, JM (May 2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–1044. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.; Supplementary Material

- ^ Wilson, James F.; Weale, Michael E.; Smith, Alice C.; Gratrix, Fiona; Fletcher, Benjamin; Thomas, Mark G.; Bradman, Neil; Goldstein, David B. (2001). "Population genetic structure of variable drug response". Nature Genetics. 29 (3): 265–9. doi:10.1038/ng761. PMID 11685208.

- ^ a b Underhill PA; Shen P; Lin AA (November 2000). "Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations". Nature Genetics. 26 (3): 358–61. doi:10.1038/81685. PMID 11062480.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cruciani F; Santolamazza P; Shen P (May 2002). "A Back Migration from Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa Is Supported by High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Haplotypes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1197–214. doi:10.1086/340257. PMC 447595. PMID 11910562.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Semino O, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, Falaschi F, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA (January 2002). "Ethiopians and Khoisan Share the Deepest Clades of the Human Y-Chromosome Phylogeny". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (1): 265–8. doi:10.1086/338306. PMC 384897. PMID 11719903.

- ^ a b c Moran et al. (2004)[1] Y chromosome haplogroups of elite Ethiopian endurance

- ^ a b Shenn et al. (2004)[2] Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation

- ^ Cruciani et al. (2004)[3] Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa

- ^ Cruciani F; La Fratta R; Trombetta B (June 2007). "Tracing past human male movements in northern/eastern Africa and western Eurasia: new clues from Y-chromosomal haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–11. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. PMID 17351267.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Semino O; Magri C; Benuzzi G (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Chiaroni J, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL (December 2009). "Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift and cultural evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (48): 20174–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910803106. PMC 2787129. PMID 19920170.

- ^ a b Kivisild T; Reidla M; Metspalu E (November 2004). "Ethiopian Mitochondrial DNA Heritage: Tracking Gene Flow Across and Around the Gate of Tears". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (5): 752–70. doi:10.1086/425161. PMC 1182106. PMID 15457403.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Passarino, G; Semino, O; Quintanamurci, L; Excoffier, L; Hammer, M; Santachiarabenerecetti, A (1998). "Different genetic components in the Ethiopian population, identified by mtDNA and Y-chromosome polymorphisms". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (2): 420–34. doi:10.1086/301702. PMC 1376879. PMID 9463310.

- ^ Hunley, Keith L.; Healy, Meghan E.; Long, Jeffrey C. (2009). "The global pattern of gene identity variation reveals a history of long-range migrations, bottlenecks, and local mate exchange: Implications for biological race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20932. PMID 19226641.

- ^ Relethford, John H. (2009). "Race and global patterns of phenotypic variation". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20900. PMID 19226639.

- ^ ScottRA, Mitochondrial DNA lineages of elite Ethiopian athletes, Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 Mar;140(3):497-503.

- ^ Musilová et al. (2011), Population history of the Red Sea—genetic exchanges between the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa signaled in the mitochondrial DNA HV1 haplogroup, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 145: n/a. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21522

- ^ Černý et al. (2008), Regional differences in the distribution of the sub-Saharan, West Eurasian and South Asian mtDNA lineages in Yemen, Volume 136, Issue 2, pages 128–137, June 2008.

- ^ a b [4] Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/EthiopiaAndTheOriginOfCivilization/EOC_djvu.txt.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, pp. 57f.

- ^ For an overview of this influence see Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible, pp. 73ff.

- ^ Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave. p. 37. ISBN 0-312-22719-1.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard K. P. Addis Tribune, "Let's Look Across the Red Sea I", January 17, 2003.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: a Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), p. 13.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270-1527 (London: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 22-3.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 36

- ^ Taddesse, Church and State, pp. 38-41.

- ^ Tekeste Negash, ""The Zagwe period re-interpreted: post-Aksumite Ethiopian urban culture."" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (51.4 KiB) - ^ Tekeste, "Zagwe period-reinterpreted."

- ^ Taddesse, Church and State, pp. 64-8.

- ^ Girma Beshah and Merid Wolde Aregay, The Question of the Union of the Churches in Luso-Ethiopian Relations (1500-1632) (Lisbon:Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 1964), pp. 13f.

- ^ Girma and Merid, Question of the Union of the Churches, p. 25.

- ^ Girma and Merid, Question of the Union of the Churches, pps.45-52

- ^ Girma and Merid, Question of the Union of the Churches, pps.91;97-104.

- ^ Girma and Merid, Question of the Union of the Churches, pp.105.

- ^ van Donzel, Emeri, "Fasilädäs" in Siegbert Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 500.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard, The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles, (London:Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. 139-143.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard. "A History of Early Twentieth Century Ethiopia". Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Clapham, Christopher, "Ḫaylä Śəllase I" in Siegbert von Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), pp. 1062-3.

- ^ Clapham,"Ḫaylä Śəllase I", Aethiopica, p. 1063.

References

- E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Ethiopian People. Their Rights and Progress. Woodford Green, Essex: New Times & Ethiopia News 1946.

- Habesha Union [ሐበሻ] . “What Do You Mean by Habesha? — A Look at the Habesha Identity (P.s./t: It’s Very Vague, Confusing, & Misunderstood) | @habesha_union.” Academia, 1 Oct. 2018.

- Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: an introduction to country and people. London: Oxford University Press 1960, ²1965, ³1973 (ISBN 0-19-285061-X), ⁴1990 (Wiesbaden: F. Steiner; ISBN 3-515-05693-9).