Women in Ghana

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2017) |

| |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 350 (2008) |

| Women in parliament | 13.5% (2017) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 45.7% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 66.9% (2011) |

| Gender Inequality Index | |

| Value | 0.565 (2012) |

| Rank | 121st |

| Global Gender Gap Index[1] | |

| Value | .06845 (2013) |

| Rank | 63rd |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The social roles of women in Ghana have varied throughout history. The overall impact of women in Ghanaian society has been significant. The social and economic well-being of women as mothers, traders, farmers, and office workers has evolved throughout centuries and is continuing to change in modern day. Life for women in Ghana varies by generation, location, and culture.[2]

Politics

Ghana does not have equal representation in politics. Although women are guaranteed political participation rights under the 1992 Ghana Constitution, there is a lack of female representation in government. There has never been a female president in Ghana. In 2012, 19 women occupied seats in Parliament, while 246 men occupied the rest of the seats.[3] In 2017, the number of women elected to Parliament grew, and 37 women were elected.[4]However, Ghanian women still make up only 13.5% of Parliament.[5]In the courts, the Chief Justice is Sophia Akuffo, the second women to be appointed to this position. The first women to hold be appointed as Chief Justice was Georgina Wood. Additionally, women only make up a small percentage of the total judges in high and Supreme Courts. In 2009, 23% of Supreme Court judges were women.[6]

There has been a slow increase of women in Parliament since the adoption of the multiparty systemin 1992.[7] Ghana has taken multiple steps to increase equality in the political sphere. For example, the government signed and ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination(CEDAW). There are many institutions in Ghana that work to advance women's rights and welfare issues. Women's groups and activists in Ghana are demanding for gender polices and programs to improve the livelihood of women.[8] Additionally, the government has a ministry dedicated to women and the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection focuses on policy formation on issues that pertain specifically to women and children. Despite the efforts of NGO's and political parties female participation in politics in Ghana remains low.[9]

The lack of political participation from women in Ghana can be attributed to longstanding cultural norms.[10] The traditional belief that women in Ghana should not have responsibilities outside the home contributes to the deficiency of women in politics.[11] Leadership is also a skill that is traditionally associated with boys and men. When women in Ghana take leadership positions, they can face discrimination.[12]

Family structure

Marriage

Polygyny refers to marriages in which men are permitted to have more than one wife at the same time. In precolonial times, polygyny was encouraged, especially for wealthy men. Anthropologists have explained the practice was a traditional method for well-to-do men to procreate additional labour. Additionally, polygamy was traditionally seen as a source of labor for men, as multiple wives allowed for more unpaid labor.[13] In patrilineal societies, dowry received from marrying off daughters was also a traditional means for fathers to accumulate additional wealth.[14] Today, the percentage of women in polygynous marriages in rural areas (23.9%) is almost double that of women in urban areas (12.4%).[15] The age group with the most women in polygynous marriages is 45–49, followed by the 15–19 age group and the 40–44 group.[15] Rates of polygynous marriages decrease as education level and wealth level increase.[15]

In traditional societies, marriage under customary law was often arranged or agreed upon by the fathers and other senior kinsmen of the prospective bride and bridegroom.This type of marriage served to link the two families/groups together in social relationships; hence, marriage within the ethnic group and in the immediate locality was encouraged.The age at which marriage was arranged varied among ethnic groups, but men generally married women somewhat younger than they were. Some of the marriages were even arranged by the families long before the girl attained puberty. In these matters, family considerations outweighed personal ones – a situation that further reinforced the subservient position of the wife.[14]

The alienation of women from the acquisition of wealth, even in conjugal relationships, was strengthened by traditional living arrangements. Among matrilineal groups, such as the Akan, married women continued to reside at their maternal homes. Meals prepared by the wife would be carried to the husband at his maternal house. In polygynous situations, visitation schedules would be arranged. The separate living patterns reinforced the idea that each spouse is subject to the authority of a different household head, and because spouses are always members of different lineages, each is ultimately subject to the authority of the senior men of his or her lineage. The wife, as an outsider in the husband's family, would not inherit any of his property, other than that granted to her by her husband as gifts in token appreciation of years of devotion. The children from this matrilineal marriage would be expected to inherit from their mother's family.[14]

The Dagomba, on the other hand, inherit from fathers. In these patrilineal societies where the domestic group includes the man, his wife or wives, their children, and perhaps several dependent relatives, the wife was brought into closer proximity to the husband and his paternal family. Her male children also assured her of more direct access to wealth accumulated in the marriage with her husband.[14]

Today, marriage dynamics generally vary between rural and urban areas. Polygyny is more common in rural areas, and a married woman is usually supported by large groups of relatives as well as co-wives.[16] Urban Ghana has generally adopted a more "Western" practice of marriage. The urban woman is held more responsible for choosing her own husband as it is not based on lineage or her family's interests. Furthermore, the urban woman is seen as more of a partner than as a minor, as she would be in many rural settings.[16] That being said, it can often be harder for the urban woman to address grievances or leave her husband because of that responsibility and lack of familial support that rural women often have.[16]

Ghana’s child protection law, the Children’s Act, prohibits child marriage; however, data from 2011 shows that 6% of girls nationwide were married before the age of 15.[15] Between 2002 and 2012, 7% of adolescent females (aged 15–19) were currently married.[17] Most of these women live in the Volta, Western, and Northern regions, and generally live in rural areas regardless of region.[15]

Familial roles

Women in premodern Ghanaian society were seen as bearers of children, farmers and retailers of produce. Within the traditional sphere, the childbearing ability of women was explained as the means by which lineage ancestors were allowed to be reborn. Barrenness was, therefore, considered the greatest misfortune. Given the male dominance in traditional society, some economic anthropologists have explained a female's ability to reproduce as the most important means by which women ensured social and economic security for themselves, especially if they bore male children.[14]

Rates of female-headed households are on the rise in Ghana. The number of female-headed households who are either widowed or divorced has also risen over time.[18] Contrary to worldwide findings that female poverty is correlated with higher rates of female-headed households, findings from the Ghana Living Standards Survey indicate that female-headed households may not actually experience higher poverty than male-headed households.[18] This is because reasons that households are headed by females differ across the country. Marital status is a significant factor in understanding differences in poverty rates. For example, widows are the group of female-headed households that exhibit the highest rates of poverty.[18] Especially in polygynous cases, not all women live in the same household as their husband.[19] Therefore, female-headed households headed by married women are best-off in terms of poverty, followed by divorced females, and widowed females.

Social norms and assigned roles for women is one of Ghana’s main issues. There are social standards that women in Africa have to follow, depending on their culture and religion. There are other factors which compound a woman’s social norms. An example of this is, president's wives in Africa are required to be present at official functions, yet preferably sons. Along with there being huge probability of a husband to take another wife if they are not successful to provide a son.[20] A way to fix social norm is by making enrollment higher for women at schools due to higher knowledge of the topic, and higher positioning of women throughout the continent. Being able to change expectations put onto women and rules that cultures have, is difficult due to having to change the mindset of either a culture, a religion or a government.

Overall, women in female-headed households bear more household and market work than do men in male-headed households, mostly because usually the female head of household is the only adult who is of working age or ability. Men are usually able to distribute work with a female spouse in male-headed households, as most men in male-headed households are married.[19] Additionally, the amount of domestic work performed by women when living with or without a spouse does not vary, leading to the conclusion that males generally make little to no significant contribution to domestic work.[19] Further, women who are the heads of household generally own about 12 fewer hectares of land than male heads of household. The disparity in land ownership increases as wealth increases.[18]

Family size

In their Seven Roles of Women: Impact of Education, Migration, and Employment on Ghanaian Mother (International Labour Office, 1987), Christine Oppong and Katherine Abu recorded field interviews in Ghana that confirmed a traditional view of procreation. Citing figures from the Ghana fertility survey of 1983, the authors concluded that about 60 percent of women in the country preferred to have large families of five or more children. The largest number of children per woman was found in the rural areas where the traditional concept of family was strongest. Uneducated urban women also had large families.[14]

On the average, urbanized, educated, and employed women had fewer children. On the whole, all the interviewed groups saw childbirth as an essential role for women in society, either for the benefits it bestows upon the mother or for the honour it brings to her family. The security that procreation provided was greater in the case of rural and uneducated women. By contrast, the number of children per mother declined for women with post-elementary education and outside employment; with guaranteed incomes and little time at their disposal in their combined roles as mothers and employees, the desire to procreate declined.[14]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence in Ghana is likely to happen to 1 in 3 women in Ghana.[21][22][23] There is a deep cultural belief in Ghana that it is socially acceptable to hit a woman to discipline a spouse.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30] According to a 2011 survey by MICS, 60 percent of Ghanaian women believe husbands are justified in beating their wives for a variety of reasons.[31][32][33] In 2008, 38.7 percent of ever-married Ghanaian women between the ages of 15 and 49 had experienced physical, emotional, or sexual violence by a husband or partner at some point in their lives.[34][35][36]

Reasons mentioned in the MICS report include: "if she goes out without telling him; if she neglects the children; if she argues with him; if she refuses sex with him; if she burns the food; if she insults him; if she refuses to give him food; if she has another partner; if she steals; or if she gossips." Women in Ghana with minimal education and from the lowest socioeconomic status justify domestic violence the most.[15]

The Ghanaian government in 2007 passed legislation to prosecute men who abuse their wives.[37][38][39][40]

Domestic violence is prevalent in rural areas.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] According to a report on domestic violence in Ghana, 28 percent of women and 20 percent of men experienced domestic violence in 2015.[50]

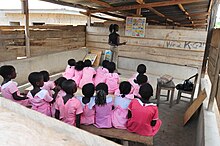

Education

The transition into the modern world has been slow for women in Ghana. High rates of female fertility in Ghana in the 1980s exhibit, historically, that women's primary role was that of child-bearing. Some parents were reluctant to send their daughters to school because their labor was needed in the home or on the farm. Resistance to female education also stems from the conviction that women would be supported by their husbands. In some circles, there was even the fear that a girl's marriage prospects dimmed when she became educated.[14]

Where girls went to school, most of them did not continue after receiving the basic education certification. Others did not even complete the elementary level of education, despite the Education Act of 1960 which expanded and required elementary school. At numerous workshops organized by the National Council on Women and Development (NCWD) between 1989 and 1990, the alarming drop-out rate among girls at the elementary school level caused great concern.

The National Council on Women and Development was founded by West Africa's first medical sociologist Professor Patrick A. Twumasi in the early 1970s. Professor Twumasi devoted much of his research and work on supporting and advocating widespread formal education for the female. One of his favorite sayings was: "educate the female, you educate the family, educate the family you educate the Nation."

Given the drop-out rate among girls, the council called upon the government to find ways to remedy the situation. The disparity between male and female education in Ghana was again reflected in the 1984 national census. Although the ratio of male to female registration in elementary schools was 55 to 45, the percentage of girls at the secondary-school level dropped considerably, and only about 17 percent of them were registered in the nation's universities in 1984. According to United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) figures published in 1991, the percentage of the female population registered at various levels of the nation's educational system in 1989 showed no improvement over those recorded in 1984.[14]

Girls' access to education has shown improvement since then. Even though women have a higher population percentage the education rates are 10 percent higher for men.[51] During 2008–12, the national literacy rate for young women aged 15–24 was 83.2%, only slightly lower than that for males of the same age group (88.3%).[17] However, literacy rates fluctuate across the country and across socioeconomic statuses. By region, literacy rates for girls range from 44% to 81%.[15] Women living at the highest socioeconomic status exhibit the highest literacy rates at 85%, while only 31% of women living in the poorest homes are literate.[15]

Inequality in gender enrollment in school remains an issue in Ghana. Economic and cultural norms factor into the decision of whether a son or daughter will attend school if a family cannot afford to send multiple children.[52] Cultural belief remains that women and girls are only for reproduction, therefore boys are sent to receive an education as it is believed they will be the breadwinner for the family.[52] A study found that urban schools in Ghana averaged two boys for every one girl.[52] Additionally, in both rural and urban areas, boys are preferred over girls for school enrollment.[52]

Based on household populations, about 50% of men and only 29% of women have attained secondary schooling or higher.[17] However, more girls are in school now and will continue into secondary school. Over the timespan of 2008-2012, 4% more girls were enrolled in preschool than boys.[17] Net enrollment and attendance ratios for primary school were both about the same for boys and girls, net enrollment standing at about 84% and net attendance at about 73%.[17] Enrollment in secondary school for girls was slightly lower than for boys (44.4% vs. 48.1%), but girls’ attendance was higher by about the same difference (39.7% vs. 43.6%).[17]

Public university education in Ghana has been found to be inequitable.[53]Women only "make up 34.9% of tertiary enrollment," and admissions preferences students who come from wealthier backgrounds.[53]

Employment

During pre-modern Ghanaian society, in rural areas of Ghana where non-commercial agricultural production was the main economic activity, women worked the land. Although women made up a large portion of agricultural work, in 1996 it was reported that women only accounted for 26.1% of farm owners or managers.[54] Coastal women also sold fish caught by men. Many of the financial benefits that accrued to these women went into upkeep of the household, while those of the man were reinvested in an enterprise that was often perceived as belonging to his extended family. This traditional division of wealth placed women in positions subordinate to men. The persistence of such values in traditional Ghanaian society may explain some of the resistance to female education in the past.[14]

For women of little or no education who lived in urban centres, commerce was the most common form of economic activity in the 1980s. At urban market centres throughout the country, women from the rural areas brought their goods to trade. Other women specialized in buying agricultural produce at discounted prices at the rural farms and selling it to retailers in the city. These economic activities were crucial in sustaining the general urban population. From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, however, urban market women, especially those who specialized in trading manufactured goods, gained reputations for manipulating market conditions and were accused of exacerbating the country's already difficult economic situation. With the introduction of the Economic Recovery Program in 1983 and the consequent successes reported throughout that decade, these accusations began to subside.[14]

Today, women make up 43.1% of economically active population in Ghana, the majority working in the informal sector and in food crop farming.[18] About 91% of women in the informal sector experience gender segregation and typically work for low wages.[18] Within the informal sector, women usually work in personal services. There are distinct differences in artisan apprenticeships offered to women and men, as well. Men are offered a much wider range of apprenticeships such as carpenters, masons, blacksmiths, mechanics, painters, repairers of electrical and electronic appliances, upholsters, metal workers, car sprayers, etc. In contrast, most female artisans are only involved in either hairdressing or dressmaking.[18] Women generally experience a disparity in earnings, receiving a daily average of 6,280 cedis compared to 8,560 cedis received by men according to the Ghana Living Standards Survey.[18]

Women are flourishing in teaching professions. Early 1990s' data showed that about 19 percent of the instructional staff at the nation's three universities in 1990 was female. Of the teaching staff in specialized and diploma-granting institutions, 20 percent was female; elsewhere, corresponding figures were 21 percent at the secondary-school level; 23 percent at the middle-school level, and as high as 42 percent at the primary-school level. Women also dominated the secretarial and nursing professions in Ghana. Although women have been assigned secretarial roles, some women are bridging the gap by learning how to code and take on men's role such as painters, electricians etc. This is changing the discourse of how the role of women in the workplace and the nature of their jobs are evolving with time. When women were employed in the same line of work as men, they were paid equal wages, and they were granted maternity leave with pay.[14] However, women in research professions report experiencing more difficulties than men in the same field, which can be linked to restricted professional networks for women because of lingering traditional familial roles.[55]

Crimes Against Women

Domestic Violence

Rape

Female Genital Mutilation

Trafficking

Witch Camps

Witch Camps can be found at Bonyasi, Gambaga, Gnani, Kpatinga, Kukuo and Naabuli, all in Northern Ghana.[56][57][58] Women have been sent to these witch camps when their families or communities believe they have caused harm to the family.[56][57] Many women in such camps are widows. It is thought that relatives accused them of witchcraft in order to take control of their husbands' possessions.[59] Many women also are mentally ill, a problem that is not well understood in Ghana.[60][59] The government has said they intend to close these camps down.[57]

Health

Reproduction related cases are the cause of many health problems for women in Ghana. According to UNICEF, the mortality rate for girls under five years old in 2012 was 66 per 1,000 girls. This number was lower than that for boys, which was 77 per 1,000.[17]

HIV/AIDS

Out of an estimated 240,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in Ghana, about half are women.[17] During the span of 2008-2012, 36.8% of young women aged 15–24 and 34.5% of adolescent girls exhibited comprehensive knowledge about the prevention of HIV/AIDS, which is defined by UNICEF as being able to "correctly identify the two major ways of preventing the sexual transmission of HIV (using condoms and limiting sex to one faithful, uninfected partner), who reject the two most common local misconceptions about HIV transmission, and who know that a healthy-looking person can have HIV."[17]

Maternal health

The birthrate for adolescents (aged 15–19) in Ghana is 60 per 1000 women.[15] The rates between rural and urban areas of the country, however, vary greatly (89 and 33 per 1000 women, respectively).[15] For urban women, 2.3% of women have a child before age 15 and 16.7% of women have a child before the age 18. For rural women, 4% have a child before age 15 and 25% have a child before age 18.[15] There have been organizations that have helped with the issue of maternal health, such as the United Nations and the Accelerated Child Survival Development Program. Both fought against abortions, and reduced about 50 percent of the child and maternal mortality rates.[61]

Among women 15–49 years old, 34.3% are using contraception.[17] Contraception use is positively correlated with education level.[15] Sometimes, women want to either postpone the next birth or stop having children completely, but don’t have access to contraception. According to MICS, this is called unmet need.[15] Prevalence of unmet need is highest for women aged 15–19 (61.6%).[15] Highest rates of met need for contraception are found in the richest women, women with secondary education or higher, and women ages 20–39.[15]

In 2011, the Government of Ghana announced that it had eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus.[62] This was an achievement on the route to meeting one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), which is to reduce the maternal mortality ratio by three quarters.[15]

Pregnant women are more vulnerable to malaria due to depression of the immune system.[15] Malaria may lead to malaria-induced anemia and may also cause low births weight.[15] Pregnant women in Ghana are encouraged to sleep under a mosquito net to avoid such infections from mosquito bites. Nationally, 33% of pregnant women slept under mosquito nets in 2011, which fell short of the goal of 65% by 2011.[15] More than twice as many pregnant women sleep under mosquito nets in rural areas than in urban areas, and the same is true of uneducated women in comparison to women who had completed secondary education or higher.[15] The correlation between these two rates may be due to more educated women living in urban areas, and more uneducated women living in rural areas. In accordance, the poorest women in Ghana show the highest rates of sleeping under mosquito nets, while the richest show the lowest rates.[15]

Female genital mutilation is not as prevalent in Ghana as it is in other countries in West Africa; 3.8% of women aged 15–49 have undergone mutilation/cutting, and 0.5% of mothers aged 15–49 have at least one daughter who has been mutilated/cut.[17]

Health insurance

Among women in the poorest households, only 57.4% have ever registered with the National Health Insurance Scheme, as compared with 74.2% of women in the richest households in Ghana.[15] Women in urban areas also had higher registration rates than women in rural areas (70.9% and 66.3%, respectively).[15] In order to become a member of NHIS, one must either pay a premium, register for free maternal care, or is exempt as an indigent. Of the women who achieved NHIS membership, 28.6% paid for the premium themselves.[15] The majority of women (59.5%) had their premium paid for by a friend or relative, and only 1.0% had it paid for by their employer.[15] Most women (39.2%) who did not register for NHIS did not do so because the premium was too expensive.[15]

Women's rights

Error: no page names specified (help).

Feminist efforts

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Since then Feminist organizing has increased in Ghana as women seek to obtain a stronger role in their democratic government. In 2004, a coalition of women created the Women's Manifesto for Ghana, a document that demands economic and political equality as well as reproductive health care and other rights.[63] Within this idea of gender inequality comes other problems such as patrilineal and matrilineal inheritance, equal education, wage gaps, and social norms and assigned roles for women. These are some of the main issues Ghana faces.[20]

The practice of gender mainstreaming has been debated in Ghana. There is ongoing discourse over whether gender issues should be handled at the national level or by sector ministries and where the economic resources for the women's movement in Ghana should come from.[64] Further, critics of gender mainstreaming argue that the system increases bureaucracy and that it has moved funds and energy away from work for women's rights.[64] The women's movement in Ghana has adopted an attitude towards gender mainstreaming that is much aligned with that of the international women's movement, which is best summarized in a 2004 AWID newsletter: "Mainstreaming [should be] highlighted along with the empowerment of women" and "it appears worthwhile to pick up the empowerment of women again and bring it back to the forefront."[64]

The NCWD's is fervent in its stance that the social and economic well-being of women, who compose slightly more than half of the nation's population, cannot be taken for granted.[14] The Council sponsored a number of studies on women's work, education, and training, and on family issues that are relevant in the design and execution of policies for the improvement of the condition of women. Among these considerations the NCWD stressed family planning, child care, and female education as paramount.[14]

Notable figures

- Joyce Ababio - founder, Joyce Ababio College of Creative Design (first Fashion Design school in Ghana)

- Ama K Abrebrese - actress

- Ama Ata Aidoo - author, feminist

- Sophia Akuffo - Chief Justice of the Republic of Ghana

- Aisha Ayensu - designer, founder of Christie Browne

- Ayesha Bedwei - Tax partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers Ghana

- Farida Bedwei - Software engineer, founder of Logiciel Ghana

- Anita Erskine-Amaizo - entrepreneur, TV and radio presenter

- Shirley Frimpong Manso - founder and CEO, Sparrow Productions

- Regina Honu - Software developer and founder, Soronko Solutions

- Hannah Kudjoe - activist and nationalist who fought for an independent Ghana.

- Comfort Ocran - CEO of Legacy & Legacy, Executive Director of Springboard Roadshow Foundation, co-founder of Combert Impressions

- Charlotte Osei - Chairperson of the Electoral Commission of Ghana

- Lucy Quist - former managing director of Airtel Ghana, President of the African Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Ghana.

References

- ^ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Ghanaian women's role in development since independence". www.ghanaweb.com. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ Dzorgbo, Dan-Bright (2016). "Exploratory Study of the Current Status of the Rights and Welfare of Ghanaian Women: Taking Stock and Mapping Gaps for New Actions". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 3: 136–141.

- ^ Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Adatuu, Roland (2017-01-01). "Enhancing Women's Political Fortunes in Ghana: Is a 50/50 Campaign Realistic?". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 43–62. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Adatuu, Roland (2017-01-01). "Enhancing Women's Political Fortunes in Ghana: Is a 50/50 Campaign Realistic?". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 43–62. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Dzorgbo, Dan-Bright (2016). "Exploratory Study of the Current Status of the Rights and Welfare of Ghanaian Women: Taking Stock and Mapping Gaps for New Actions". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 3: 136–148.

- ^ Musah, Baba Iddrisu (2013). "Women and Political Decision Making: Perspectives from Ghana's Parliament". Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences. 5: 443–476.

- ^ Musah, Baba Iddrisu (2013). "Women and Political Decision Making: Perspectives from Ghana's Parliament". Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences. 5: 443–476.

- ^ Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Adatuu, Roland (2017-01-01). "Enhancing Women's Political Fortunes in Ghana: Is a 50/50 Campaign Realistic?". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 43–62. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Bukari, Francis Issahaku Malongza; Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Abagre, Cynthia Itboh (2017-01-01). "Affirmative Action as a Strategy for Promoting Women's Participation in Politics in the Frafra Traditional Area of Ghana". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 121–141. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Bukari, Francis Issahaku Malongza; Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Abagre, Cynthia Itboh (2017-01-01). "Affirmative Action as a Strategy for Promoting Women's Participation in Politics in the Frafra Traditional Area of Ghana". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 121–141. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Bukari, Francis Issahaku Malongza; Apusigah, Agnes Atia; Abagre, Cynthia Itboh (2017-01-01). "Affirmative Action as a Strategy for Promoting Women's Participation in Politics in the Frafra Traditional Area of Ghana". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (2): 121–141. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ Klingshirn, Agnes (1973). "THE SOCIAL POSITION OF WOMEN IN GHANA". Verfassung und Recht in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America. 6 (3): 290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n David Owusu-Ansah, David. "The Position of Women", in A Country Study: Ghana (La Verle Berry, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (November 1994). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Ghana" (PDF). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey with and Enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker. 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Little, Kenneth (1997). "Women's Strategies in Modern Marriage in Anglophone West Africa: an Ideological and Sociological Appraisal". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 3. 8: 341–356. JSTOR 41601020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "At a Glance: Ghana". UNICEF. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Awumbila, Mariama (2006). "Gender equality and poverty in Ghana: implications for poverty reduction strategies". GeoJournal. 67 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1007/S10708-007-90. JSTOR 41148110.

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Cynthia B.; Anastasia J. Gage-Brandon (1993). "Women's Role in Maintaining Households: Family Welfare and Sexual Inequality in Ghana". Population Studies. 1. 47: 115–131. doi:10.1080/0032472031000146766. JSTOR 2175229.

- ^ a b Bottah, Eric Kwasi (19 March 2010). "Gender Inequality and Development Paralysis in Ghana". GhanaWeb. GhanaWeb. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Name * (18 August 2016). "Research Report on Domestic Violence Launched". Ghanaguardian.com. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Domestic Violence in Ghana" (PDF). Statsghana.gov.gh. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Violence Against Women in Ghana". GBC. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Nancy Chi Cantalupo. "Domestic Violence in Ghana: The Open Secret" (PDF). Scholarship.law.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Spousal murders in Ghana worrying". Graphic. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ "In Ghana, changing the belief in violent discipline". UNICEF. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Facts on Violence Against Women in Ghana (Part 2 of 2)". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Facts on Violence Against Women in Ghana (Part 1 of 2)". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Counting the Costs of Violence Against Women and Girls In Ghana" (PDF). Whatworks.co.za. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Domestic violence on ascendancy – Today Newspaper". 30 August 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "60% Of Women Justify Wife-Beating—Survey Reveals". Modern Ghana. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ "Male Partner Violence against Women in Northern Ghana: Its Dimensions and Health Policy Implications" (PDF). Tspace.library.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Domestic Violence in Ghana: Socially Accepted and Judicially Trivialized – The Generation". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Justino, Patricia. "Domestic Violence in Ghana: Prevalence, Incidence and Causes". Institution of Development Studies. Institution of Development Studies. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Study suggests women supports wife beatings". GBC. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Peterson, Diana Scharff; Schroeder, Julie A. (19 December 2016). "Domestic Violence in International Context". Routledge. Retrieved 26 February 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Domestic Violence Bill Passed At Last". Modernghana.com. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Microsoft Word – Domestic Violence Act 732" (PDF). S3.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Lessons from Ghana:The Challenges of a Legal Response to Domestic Violence in Africa" (PDF). Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ "GHA103468.E" (PDF). Justice.gov. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "FACTORS INFLUENCING DOMESTIC AND MARITAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN GHANA" (PDF). Paa2013.princeton.edu. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Effects of violence against women in Ghana". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Domestic violence rife in rural Ghana - Africa - DW.COM - 16.06.2016". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Domestic violence in Ghana is at epidemic levels". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Abbey, Emelia Ennin. "17,655 Domestic violence cases reported to DOVVSU in 2014 - Graphic Online". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Jotie, Sule. "GHANA DOMESTIC VIOLENCE RESEARCH REPORT LAUNCHED IN ACCRA – Government of Ghana". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Owusu Adjah, Ebenezer S.; Agbemafle, Isaac (1 January 2016). "Determinants of domestic violence against women in Ghana". BMC Public Health. 16: 368. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3041-x. PMC 4852424. PMID 27139013. Retrieved 26 February 2017 – via BioMed Central.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Launch of domestic violence research report in Ghana – Speeches – GOV.UK". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Domestic Violence Board Set Up – The Ghanaian Times". Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Summary Report: Domestic Violence in Ghana: Incidence, Attitudes, Determinants and Consequences". Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ CIA Factbook. "Africa: Ghana". The CIA World Factbook. The Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 Apr 2016.

- ^ a b c d Mahama, Tia Abdul-Kabiru; Nkegbe, Paul Kwame (2017-01-01). "Gender Preference in Primary School Enrolment among Households in Northern Region, Ghana". Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 14 (1): 60–78. ISSN 0855-6768.

- ^ a b Yusif, Hadrat; Yussof, Ishak; Osman, Zulkifly (2013). "Public university entry in Ghana: Is it equitable?". International Review of Education / Internationale Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft / Revue Internationale de l'Education. 59 (1): 7–27.

- ^ Prah, Mansah (1996). "Women's Studies in Ghana". Women's Studies Quarterly. 24 (1/2): 412–422. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Campion, P. (2004). "Gender and science in development: women scientists in Ghana, Kenya, and India". Science, Technology, & Human Values. 29 (4): 459–485. doi:10.1177/0162243904265895.

- ^ a b "Violence against women in Ghana: a look at women's perceptions and review of policy and social responses". Social Science & Medicine. 59 (11): 2373–2385. 2004-12-01. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.001. ISSN 0277-9536.

- ^ a b c Whitaker, Kati (September 1, 2012). "Ghana Witch Camps: Widows' Lives in Exile". BBC News.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Ansah, Marian Efe (8 December 2014). "Bonyase witches' camp shuts down on Dec. 15". Citifmonline. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

BBCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Breaking the spell of witch camps in Ghana". Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Mohammed., Janet Adama. "Gender Equality and Women's Rights". Modern Ghana. Modern Ghana. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Ghana eliminates maternal and neonatal tetanus". UNICEF. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Interview with Manifesto organizers Dzodzi Tsikata, Rose Mensah-Kutin, and Hamida Harrison, conducted by Amina Mama: "In Conversation: The Ghanaian Women's Manifesto Movement", in Feminist Africa 4, 2005.

- ^ a b c Hojlund Madsen, Diana (2012). "Mainstreaming from Beijing to Ghana – the role of the women's movement in Ghana". Gender & Development. 3. 20: 573–584. doi:10.1080/13552074.2012.731746.