Wihtred of Kent

| Wihtred | |

|---|---|

| King of Kent | |

| Reign | c. 690 – 23 April 725 |

| Born | c. 670 |

| Died | 23 April 725 (aged 54–55) |

| Issue | Æthelberht II, Eadberht I, and Alric |

| Father | Ecgberht |

Wihtred (c. 670 – 23 April 725) was king of Kent from about 690 or 691 until his death. He was a son of Ecgberht I and a brother of Eadric. Wihtred ascended to the throne after a confused period in the 680s, which included a brief conquest of Kent by Cædwalla of Wessex, and subsequent dynastic conflicts. His immediate predecessor was Oswine, who was probably descended from Eadbald, though not through the same line as Wihtred. Shortly after the start of his reign, Wihtred issued a code of laws—the Law of Wihtred—that has been preserved in a manuscript known as the Textus Roffensis. The laws pay a great deal of attention to the rights of the Church (of the time period), including punishment for irregular marriages and for pagan worship. Wihtred's long reign had few incidents recorded in the annals of the day. He was succeeded in 725 by his sons, Æthelberht II, Eadberht I, and Alric.

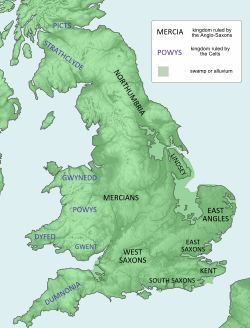

Kent in the late seventh century

The dominant force in late-seventh-century politics south of the River Humber was Wulfhere of Mercia, who reigned from the late 650s to 675. The king of Kent for much of this time was Ecgberht, who died in 673. Ecgberht's sons, Eadric and Wihtred, were probably little more than infants, two or three years old, when their father died; Wulfhere was their uncle by virtue of his marriage to Eormenhild, Ecgberht's sister. Hlothhere, Ecgberht's brother, became king of Kent, but not until about a year later, in 674, and it may be that Wulfhere opposed the accession of Hlothhere and was the effective ruler of Kent during this year-long interregnum.[1]

Eadric raised an army against his uncle and Hlothhere died of wounds sustained in battle in February 685 or possibly 686.[2] Eadric died the following year, and according to Bede, whose Ecclesiastical History of the English People is one of the primary sources for this period, the kingdom fell apart into disorder.[3] Cædwalla of Wessex invaded in 686 and established his brother Mul as king there; Cædwalla may have ruled Kent directly for a period when Mul was killed in 687.[4] When Cædwalla departed for Rome in 688, Oswine, who was probably supported by Æthelred of Mercia, took the throne for a time. Oswine lost power in 690, but Swæfheard (son of Sebbi, the king of Essex), who had been a king in Kent for a year or two, remained.[5] There is clear evidence that both Swæfheard and Oswine were kings at the same time, as each witnessed the other's charters. It seems that Oswine was king of east Kent, which was usually the position of the dominant king, while Swæfheard was king of west Kent.[6]

Accession and reign

Wihtred emerged from this disarray and became king in the early 690s.[5] Bede describes his accession by saying that he was the "rightful" king, and that he "freed the nation from foreign invasion by his devotion and diligence".[3] Oswine was also of the royal family, and arguably had a claim to the throne; hence it has been suggested that Bede's comments here are strongly partisan. Bede's correspondent on Kentish affairs was Albinus, abbot of the monastery of St. Peter and St. Paul (subsequently renamed St. Augustine's) in Canterbury, and these views can almost certainly be ascribed to the Church establishment there.[7][8][9]

Two charters provide evidence of Wihtred's date of accession. One, dated April 697, indicates Wihtred was then in the sixth year of his rule,[10] so his accession can be dated to some time between April 691 and April 692. Another, dated 17 July 694, is in his fourth regnal year, giving a possible range of July 690 to July 691.[11] The overlap in date ranges gives April to July 691 as the likely date of his accession.[12] Another estimate of the date of Wihtred's accession can be made from the duration of his reign, given by Bede as thirty four and a half years. He died on 23 April 725, which would imply an accession date in late 690.[13]

Initially Wihtred ruled alongside Swæfheard.[5] Bede's report of the election of Beorhtwald as Archbishop of Canterbury in July 692 mentions that Swæfheard and Wihtred were the kings of Kent, but Swæfheard is not heard of after this date. It appears that by 694 Wihtred was the sole ruler of Kent,[5] though it may also be that his son Æthelberht was a junior king in west Kent during Wihtred's reign.[14] Wihtred is thought to have had three wives. His first was called Cynegyth, but a charter of 696 names Æthelburh as the royal consort and co-donor of an estate: the former spouse must have died or been dismissed after a short time. Near the end of his reign, a new wife, Wærburh, attested with her husband and son, Alric.[15]

It was also in 694 that Wihtred made peace with the West Saxon king Ine. Ine's predecessor, Cædwalla, had invaded Kent and installed his brother Mul as king, but the Kentishmen had subsequently revolted and burned Mul. Wihtred agreed compensation for the killing, but the amount paid to Ine is uncertain. Most manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record "thirty thousand", and some specify thirty thousand pounds. If the pounds are equal to sceattas, then this amount is the equal of a king's wergild—that is, the legal valuation of a man's life, according to his rank.[16][17] It seems likely that Wihtred ceded some border territory to Ine as part of this settlement.[18]

Laws

The earliest Anglo-Saxon law code to survive, which may date from 602 or 603, is that of Æthelberht of Kent, whose reign ended in 616.[19] In the 670s or 680s, a code was issued in the names of Hlothhere and Eadric of Kent. The next kings to issue laws were Ine of Wessex and Wihtred.[20]

The dating of Wihtred’s and Ine’s laws is somewhat uncertain, but there is reason to believe that Wihtred’s laws were issued on 6 September 695,[21] while Ine’s laws were written in 694 or shortly before.[22] Ine had recently agreed peaceful terms with Wihtred over compensation for the death of Mul, and there are indications that the two rulers collaborated to some degree in producing their laws. In addition to the coincidence of timing, there is one clause that appears in almost identical form in both codes.[23] Another sign of collaboration is that Wihtred’s laws use gesith, a West Saxon term for noble, in place of the Kentish term eorlcund. It is possible that Ine and Wihtred issued the law codes as an act of prestige, to re-establish authority after periods of disruption in both kingdoms.[24]

Wihtred's laws were issued at "Berghamstyde"; it is not known for certain where this was, but the best candidate is Bearsted, near Maidstone. The laws are primarily concerned with religious affairs; only the last four of its twenty-eight chapters do not deal with ecclesiastical affairs. The first clause of the code gives the Church freedom from taxation. Subsequent clauses specify penalties for irregular marriages, heathen worship, work on the sabbath, and breaking fasts, among other things; and also define how members of each class of society—such as the king, bishops, priests, ceorls, and esnes—can clear themselves by giving an oath.[25] In addition to the focus of the laws themselves, the introduction makes clear the importance of the Church in the legislative process. Bertwald, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was present at the assembly which devised the decrees, and so was Gefmund, the Bishop of Rochester; and "every order of the Church of that nation spoke in unanimity with the loyal people".[25][26]

The privileges given to the Church are notable: in addition to the freedom from taxation, the oath of a bishop is "incontrovertible", which places it at the same level as the oath of a king, and the Church receives the same level of compensation for violence done to dependents as does the king. This has led one historian to describe the Church's power, less than a century after the original Roman mission landed in Kent, as "all but co-ordinate with the king himself in the Kentish state",[27] and it has also been described as presupposing "a frightening degree of royal power".[28] However, the presence of clauses that provide penalties for any of Wihtred's subjects who "sacrifice to devils" makes it clear that although Christianity was dominant, the older pagan beliefs of the population had by no means died out completely.[25][29]

Clause 21 of the code specifies that a ceorl must find three men of his own class to be his "oath-helpers". An oath-helper would swear an oath on behalf of an accused man, to clear him from the suspicion of the crime. The laws of Ine were more stringent than this, requiring that a high-ranking person must be found to be an oath-helper for everyone, no matter what class they were from. The two laws taken together imply a significant weakening of an earlier state in which a man's kin were legally responsible for him.[30]

Death and succession

On his death, Wihtred left Kent to his three sons: Æthelberht II, Eadberht I, and Alric.[13] The chronology of the reigns following Wihtred is unclear, although there is evidence of both an Æthelbert and at least one Eadbert in the following years.[31] After Wihtred's death, and the departure of Ine of Wessex for Rome the following year, Æthelbald of Mercia became the dominant power in the south of England.[32]

See also

Notes

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 115.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 118.

- ^ a b Bede, Ecclesiastical History, IV. 26, p. 255.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c d e Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 32.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 53.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 182.

- ^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 25.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 18". Sean Miller. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 15". Sean Miller. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ Note that Kirby uses S18 in his argument for Wihtred's accession date, whereas Whitelock uses S15. See Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 123; and Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 361.

- ^ a b Bede, Ecclesiastical History, V. 23, p. 322–325.

- ^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 33.

- ^ Kelly, Wihtred. The charter of 716, which recorded a Synod at Bapchild in Kent, is regarded as spurious, but is thought to have used genuine witness lists.

- ^ Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 40–41, note 3.

- ^ Lapidge, Michael (ed.), "Wergild", in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 469.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 124.

- ^ Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 357.

- ^ Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 327–337.

- ^ Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 361.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 72.

- ^ The law is chapter 20 in Ine's code, and chapter 28 in Wihtred's. Ine's version reads "If a man from a distance or a foreigner goes through the wood off the track, and does not shout nor blow a horn, he is to be assumed to be a thief, to be either killed or redeemed." Wihtred's version is "If a man from a distance or a foreigner goes off the track, and he neither shouts nor blows a horn, he is to be assumed to be a thief, to be either killed or redeemed." See Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 364, 366.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 362–364.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 2.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 62

- ^ Wormald, Patrick, "The Age of Bede and Aethelbald", in Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, p. 99

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 128

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 30–31.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.131.

References

Primary sources

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price, revised R.E. Latham, ed. D.H. Farmer. London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044565-X

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968). English Historical Documents v.l. c.500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Secondary sources

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Kelly, S. E. (2004). "Wihtred (d. 725), king of Kent". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29381. Retrieved 27 November 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

External links