Boy

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2009) |

| Part of a series on |

| Masculism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

A boy is a young male human, usually a child or adolescent. When he becomes an adult, he is described as a man. The most apparent difference between a typical boy and a typical girl is the genitalia. However, some intersex children with ambiguous genitals, and genetically female transgender children, may also be classified or self-identify as a boy.

The term boy is primarily used to indicate biological sex distinctions, cultural gender role distinctions or both. The term can be joined with a variety of other words to form these gender-related labels as compound words.

Etymology

The word "boy" comes from Middle English boi, boye ("boy, servant"), related to other Germanic words for boy, namely East Frisian boi ("boy, young man") and West Frisian boai ("boy"). Although the exact etymology is obscure, the English and Frisian forms probably derive from an earlier Anglo-Frisian *bō-ja ("little brother"), a diminutive of the Germanic root *bō- ("brother, male relation"), from Proto-Indo-European *bhā-, *bhāt- ("father, brother"). The root is also found in Norwegian dialectal boa ("brother"), and, through a reduplicated variant *bō-bō-, in Old Norse bófi, Dutch boef "(criminal) knave, rogue", German Bube ("knave, rogue, boy"). Furthermore, the word may be related to Bōia, an Anglo-Saxon personal name.

In English, the words youth, teenager and adolescent may refer to either male or female. No gender-specific term exists for an intermediate stage between a boy and a man, except "young man", although the term puberty, for one who reached sexual reproductivity (or the legally assumed age, e.g. 14 for boys, often set lower for girls) without being a legal adult yet, stems from a Latin word for boys only, itself named after the accompanying male body hair, pubes, on face and genital region.

Usage for adults

Many occasions occur when an adult male is commonly referred to as a boy. A person's boyfriend or loverboy may be of any age; this even applies to a 'working' call-boy, toyboy (though younger than his lover). Reflecting the general aesthetic preference for youth, one says pretty boy (e.g. in the nickname of Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd, who committed his first bank robbery at age 30) or Adonis (name of a mythological youth) even when a male beauty is clearly of riper age. In terms (used pejoratively or neutrally) for homosexuals such as batty boy (alongside "batty man"; from "bottom") or "bum boy", age is not essential, but the connotation of immaturity can strengthen insulting use.

Groups of adult male friends engaged in male bonding are often called "the boys". It is most common to refer to men, irrespective of age or even in an adult age group, as boys in the context of a team (especially all-male), such as old boys for networking of adult men who attended the same school(s) as boys, or as professional colleagues, e.g. "the boys at the office, - police station etc." (often all adults). The members of a student fraternity can be called frat(ernity) boys, technically preferable to the pleonasm frat-bro(ther), and remain so for life as adults, after graduation.

In sports 'the boys' commonly refers to the teammates; e.g., UK football managers quite often refer to their players as "The boy so-and-so" and this usage is by no means restricted to the youngest players, though it is rarely applied to the most senior.

In US urban slang, particularly in African American and Latino slang, the term boy is used with a possessive as meaning friend (my boy, his boys), presumably as a reduction of homeboy, originally a male from the same area.

In some cases, the word boy is used merely to designate the age of the (male) person, irrespective of the function, as in altar boy, a minor acting as liturgical acolyte, or in Boy Scouts, an organisation specifically for boys. Thus the compound -man can then be replaced by -boy, as in footboy; or boy is simply added, either as a prefix (e.g., in boy-racer) or as a suffix (e.g., in Teddy Boy).

An adult equivalent (with or without -man) is not to be expected when -boy designates an apprentice (for which some languages use a compound with the equivalent of boy, e.g. leerjongen 'learning boy' in Dutch) or lowest rank implying specific on the job training if promotion is to be obtained, as in kitchen boy. Similarly schoolboy only applies to minors; the modern near-synonym pupil originally designated a minor in Roman law as being under a specific adult's authority, as in loco parentis.

Expressions such as "boys will be boys" (i.e., a male always retains a tendency for boyish games or mischief) allude to stereotypically ascribed characteristics of boys and men; in the term tomboy, a woman's (according to the counterpart-gender stereotype) uncharacteristically bold nature is even described solely by comparing her to a boy.

The use of boy (like kid) in (fantasy or descriptive) nicknames, also for adult men (e.g. Shark Boy for a wrestler with matching costume), may also connote to the informal or naughty image of boyhood.

In such terms as 'city boy' or 'home boy', the age notion is at most anachronistic, as they indicate any male who grew up (or by extension lived a long time) in a certain environment.

Characteristics of boys

Ongoing debates about the influences of nature versus nurture in shaping the behavior of girls and boys raises questions about whether the roles played by boys are mainly the result of inborn differences or of socialization. Images of boys in art, literature and popular culture often demonstrate assumptions about gender roles. In some Middle Eastern cultures, characteristics affirming boyhood include physiological features associated with prepubescence, such as pubelessness and the inability to ejaculate.[1][2] An adult male human is a man, but when age is not a crucial factor, both terms can be interchangeable, e.g., 'boys and their toys' applies equally to adults and young boys, just as 'Are you mice or men?' can also apply to young boys.

The age boundary is not clear cut, rather dependent on the context or even on individual circumstances. A young man who has not assumed (or has been denied) the traditional roles of a man might also be called a boy. It may feel uncomfortable to a young male upon being referred to as a "man" before he believes he has assumed these roles, such as having a career, a partner, a household of his own, fatherhood, etc., though the addition of a jocular modifier such as "young man" or "little man" might lessen the dissonance. Conversely, it may feel uncomfortable to a male to be called a "boy" if he believes he has assumed the traditional roles of a "man". In mother's/mama's boy, the word emphatically implies a male (minor or adult in years) who is too immature to be independent.

In some traditions boyhood is held to be exchanged for adult manhood, or at least approach it significantly, by certain -in se independent- acts assuming a role deemed to be typical for a "normal" man (though there are limits) as marriage, fathering offspring or military service. Various cultural and/or religious rites of passage serve, partially or specifically, to mark the transition to manhood.

There is often a number of traditional differences in attire between boys and adult men, which may even give rise to a metaphoric term such as broekvent in Dutch (i.e., a boy who has not yet "graduated" from shorts to trousers) and in what is socially accepted as appropriate behaviour, e.g., boys may be publicly seen naked in cultures where men are not.

Specific uses and compounds

The following subsections treat some specific contexts where the term boy is frequently used, as such or in compound terms, often 'emancipated' from the age notion as such.

- Master was replaced (not for a slave owner or his overseer etc.) by the late 19th century, as a form of address, especially employed by servants, by Mister (etymologically equal) for the master of the household and other adults, but retained for boys until age 13.

Military

The term 'our boys' is commonly used for a nation's soldiers, often with sympathy. Given the physical demands of battle, recruits are preferably in their physical prime, but adult professionals remain included in the term as long as they remain in service. A case where the term is formally used for (adult) men is sideboy, a member of an even-numbered group of seamen posted in two rows at the Quarterdeck when a visiting dignitary boards or leaves a ship. In the Ottoman Empire, the young, mainly Christian military recruits for life (often forcibly enlisted by 'devshirme') were officially called acemi oglanlar ("novice boys").

Thus "-boy" can enter the nickname for a particular nation's soldiers, e.g. the US (infantry) doughboy, or a specific force, e.g. Fly-boy is slang for an airman.

Furthermore, specific terms refer to minors used in the armed forces:

- Drummer boy

- Ship's boy is a minor in naval training; boy seaman refers to specific, low-paid apprentice ranks, notably in the Royal Navy; until the middle of the twentieth century, they were the only Navy staff subject (like their civilian age-peers, at home and in school) to physical punishment, usually spanking, traditionally administered on the bare bottom (as in English public schools; the adults were lashed on the backside above the waist), either formally (ordered in court martial, publicly executed on deck) or, more often but less severely, summary; the same was true of a midshipman, also a minor, but indicated with "-man" rather than "-boy", possibly reflecting their higher status as future naval officers. Sometimes in ex-servicemen's parades, an old man is described as "ship's boy" to say that he served so classed in the Navy as a boy.

However, when a minor in military employ is considered (historically often far less restrictive then nowadays) too young to be a 'normal' warrior (illegal under present UN rules, but without precise enforceable age limits), he's called boy soldier, regardless whether he's used as an armed fighter or only in logistic or similar functions such as bearer.

Domestic, residential and similar 'personal' attendants

- Bellboy was originally a ship's bell-ringer, later a hotel page.

- Busboy is a rank in restaurants etc. below (head) waiter, fitting for trainees but may be held by ripe adults, even under younger (e.g. better qualified) superiors

- Cabana boy

- Cabin boy

- Hall boy

- Hamam oğlanı "bath boy" (also called Tellak) working in a Turkish bath.

- Houseboy, or often "boy" for short, became a common term for domestic staff, notably non-European natives in the Asian and African colonies, adopted as such in other languages, e.g. in Dutch and French (also in the Belgian colonies).

- Kitchen boy, below the cook(s); in a large household there may be specific functions, such as spitboy

- Linkboy like linkman meant torch- or other light-bearer

- Page, from the Greek παις pais, again in many languages, already in Hellenistic times παίδες βασιλικοί paides basilikoi 'royal (i.e. court) boys'.

Cultural and religious life

- Altar boy (see above)

- Choir boy designates a boy (always a minor) singer in a choir; here applies a specific physiological, artistically relevant criterion: they remain a musical category of their own (boy soprano, also known as a treble) until their voice 'breaks', during puberty, to join one of the adult male voice registers (countertenor (closest to treble), alto, tenor, baritone, or bass); only the castrato may (not guaranteed) remain a soprano as an adult man; historically the term was designed for all-male (mainly church) choirs, with men with already broken voices (often former choir boys), in modern times it also applies to mixed choirs.

- Boys' game

Rural life and professions

- Cowboy originally designated a herdsboy employed as cowherd, but lost the age notion, first retaining the connotation of inferior status, later applying to the whole ranch life culture; by contrast "shepherd's boy" (rather herding sheep or goats, representing less capital) remained restricted to minors.

Commercial and other services

Often the term "boy" describes positions of the trainee type, such as stable boy (a junior stable hand).

- Best boy in a film crew denotes the chief assistant, usually of the gaffer or key grip, next in line to be promoted; an example of a use where the term is traditionally unaltered in crediting female incumbents

- Breaker boys were boys between 8 and 12 years old who worked as coal breakers in U.S. coal mines. The job resulted in a high number of fatal and debilitating injuries and the practice of employing children as coal breakers largely ended by 1920 due to the efforts of the National Child Labor Committee.

- Office boy and copy boy refer to a young(est) employee (i.e. lacking experience), in training and/or performing menial services such as carrying typewritten texts between offices of a newspaper.

- Even into the early 20th century, the British empire systematically employed boy clerks, including a specific rank of boy copyist, recruited by examination (despite the name, requiring schooling) and reserved for candidates aged 15–18, not retained in that rank after the age of 20.

Certain jobs need so little training or formal qualifications that they can easily be performed as student jobs, and thus tend to be filled mostly or exclusively by minors, as it would not pay to employ an adult at or above minimum wage. Thus an equivalent word with the compound man (or similar) may be the rarer one, or even inexistent. Examples include delivery boy, errand boy, messenger boy and various specific terms naming the product to deliver, such as paperboy (closest adult counterpart postman), pizza boy (alongside pizzaman), or to serve, such as a potboy (drinks waiter, or a gather of empties). In other cases the compound mentions a crucial attribute of his task, e.g. ball boy (more recently also girls) in tennis.

In some cases his small, light body makes a boy a better choice, e.g. as jockey where no weight handicap is in force.

- A nipper originally was a boy send out by an adult (often his own father) as pickpocket, later a boy assistant to various professions such as a carter, still later (recorded since 1859) a boys' age term roughly equal to toddler

Race

Historically, in the US and South Africa, "boy" was not only a "neutral" term for domestics but also as a disparaging term towards men of color, implying their subservient status.[3][4][5][6] The usage ran from the period of slavery through segregation and apartheid, though it became less acceptable and decreased as time passed.[citation needed]

The use of the term "boy" has not always been used as an insult. As an example, Thomas Branch, an early African-American Seventh-day Adventist missionary to Nyassaland (Malawi) referred to the native students as boys:

There is one way by which we judge many of our present boys to be quite different from some of those who were here long ago: those that are married have their wives here with them, and build their own houses, and all are busy making their gardens. I have told all the boys that if they wished to stay here and learn, those that had wives must bring them. This is having a good effect on them. They stay longer, and are more attentive to their work and their studies.[7]

Multiple politicians – including New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and former Kentucky Congressman Geoff Davis – have been criticized publicly for referring to a black man as "boy."[5][6]

During an event promoting the boxing bout between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Conor McGregor, the latter told to the former to "dance for me, boy."[8] The remarks led several boxers – including Mayweather and Andre Ward – as well as multiple commentators to accuse McGregor of racism.[8][9][10][11]

Non-function specific analogous terms

Boys, in the strict or a wider sense, are often informally referred to by analogous or metaphorical terms. The literal connotations, which may be ironic or downright pejorative, have often been eroded by common use. Some terms are unisex, with or without (at least historical) preponderance of use for boys:

- Cub, pup(py) and whelp compare boys to the young of predatory animals, the slang tadpole even to that of an amphibian;

- Buck, another animal young, usually refers to a sexually adventurous male youngster

- Loon, originally an (idle) lout, has got -mainly in Scotland- unrelated specific meanings, including boy, simpleton and looney person

- Sprout compares to a plant's young shoots

- References to the boy's generally lighter physique than a man include stripling 'slender youth' and -rather insulting- slang like half-pint or small-fry

- More specifically, shaveling (or in slang shaver) refers to boys' lesser hair growth than men's before - and densification around puberty

- Various terms refer to children's, often especially boys', lack of adult manners (e.g. "snot(ty) nose(d) (kid)") or to often mischievous behavior, e.g. "rascal", also by analogy with animals, e.g. "monkey", "urchin" (as 'prickly' as a hedgehog); "(spoiled) brat" refers to such undiscipline for lack of firm upbringing.

- Furthermore, common boys' names have also been used metonymically to stand for boys and/or men in general, as in 'every Dick and Tom'.

Analogous uses and popular etymology

By analogy, "boy" can also refer as an anthropomorphic term to a young male (or any male) of another animal, either in general or species-specific; in the last case it may even have a specific term, notably derived from a name given to boys, such as "billy goat" for a 'boy' goat, or tomcat (known since 1809, for any male cat; but just tom, applied to male kittens, is recorded since c.1303)

Again, by analogy, "boy" can occasionally even refer to a 'male' object.

Some words contain 'boy' in English by mistake (folk etymology), actually referring to a (near) homophone such as French bois = "wood" (e.g. in "low boy", a type of furniture, and in "tallboy", both furniture and a high glass or goblet).

Similar originally youth-related terms

Boys in art

Many mythological boys have frequently been represented in various arts, e.g. Venus' often mischievous son Cupid, himself a young god of love which he 'inflicts' on humans by shooting his arrows; in some style periods even multiplied as naked little boys called putti.

In religious art, generally adults preponderate (except as extras), with certain marked, stereotypical exceptions such as the infant Jesus or angels which may even act as 'Christianized' putti.

In children's books of English folklore, elves are often portrayed as mischievous little boys who are very small with leaf-shaped ears and blond hair.

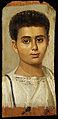

In portrait art, and generally in commissioned work (including funeral art), the subjects are usually determined by the wishes of the (adult) client, so minors are often in the minority, yet in wealthy families especially heirs are (re)presented as part of their social positioning in view of future marriage and succession, generally either as mini-adults or stereotypical youth, e.g. at play or in cozy home scenes.

Some artists displayed a clear predeliction for scenes with boys, in certain cases (especially if frequently depicting revealing poses) believed to have to do with a homo-erotic taste, as is believed of the highly respected Old Master Caravaggio, or Henry Scott Tuke who kept producing such works even though the market circa 1900 was rather unappreciative.

In music, boys' voices, before they 'break' being of a soprano register (specifically known as treble) unlike adult men (in a choir usually tenor and bass), have been most sought-after, especially where female voices were considered inappropriate as often in church and certain theatrical music - this even led to the practice of physically trying to prevent their 'angelical' voices ever to break by surgically cutting short the hormonal drive to manhood: for centuries, castrato singers, who coupled adult strength and experience with a treble register, starred in contratenor parts, mainly in operatic styles.

Gallery

-

Sir Walter Raleigh and his son, 1602

-

Die Söhne des Künstlers Christian Leberecht Vogel

-

Die Geschwister an der Ostsee, by Ernst Weise, 1915

-

Newborn baby boy

-

A young boy from Dar es Salaam

-

Boy in Spain

-

Boys in Germany, performing a puppet play

-

Two El Salvador boys playing

See also

References

- ^ Carimokam, Cahaja (2010). Muhammad and the People of the Book. p. 515.

- ^ Esposito, John (2004). The Islamic world: past and present -. p. 47.

- ^ Corriher, Billy (2011-12-21). "Court finally says 'boy' comments are racist". Harvard Law and Policy Review. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ Ifill, Sherrilyn A. (24 August 2010). "When 'Boy' Is Not a Racist Remark". The Root. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ a b Martin, Roland S. (15 April 2008). "Understanding why you don't call a black man a boy". CNN.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ a b "Racist Or Not? Gov. Chris Christie Calls Black Man 'Boy' In Town Hall [VIDEO]". News One. 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ Branch, Thomas H. (January 3, 1907). "British Central Africa" (PDF). Review and Herald. 84 (01). Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association: 18. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Press Association (2017-07-15). "Floyd Mayweather accuses Conor McGregor of racism and uses homophobic slur". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ Chiari, Mike (13 July 2017). "Andre Ward Doesn't Like Conor McGregor Calling Floyd Mayweather 'Boy'". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ Callahan, Yesha (13 June 2017). "Yes, Conor McGregor Is a Racist". The Root. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ Bell, Gabriel (14 July 2017). "Conor McGregor denies being a racist with racist statement". Salon. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- Etymology Online - entry for "boy"

- H. H. Malincrodt, Latijn-Nederlands woordenboek (Latin-Dutch dictionary)

- Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary

- Buck, Carl Darling (1988) [1949]. A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07937-0.

Further reading

- Sommers, Christina Hoff (2000). The War against Boys: How Misguided Feminism Is Harming Our Young Men. New York: Simon & Schuster. 251 p. ISBN 0-684-84956-9

External links

- Boyhood Studies, website and journal for the study of boys

- Boyhood Studies Forum, discusses news items, new research

- Historical Boys' Clothing