Mexico–United States border wall

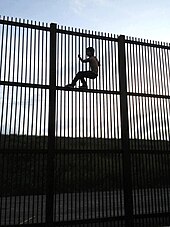

The Mexico–United States barrier (Template:Lang-es), sometimes colloquially called the Border Wall, is a series of vertical barriers along the Mexico–United States border aimed at preventing illegal crossings from Mexico into the United States.[1] The barrier is not one contiguous structure, but a discontinuous series of physical obstructions variously classified as "fences" or "walls".

Between the physical barriers, security is provided by a "virtual fence" of sensors, cameras, and other surveillance equipment used to dispatch United States Border Patrol agents to suspected migrant crossings.[2] As of January 2009, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported that it had more than 580 miles (930 km) of barriers in place.[3] The total length of the continental border is 1,954 miles (3,145 km).

History

The barriers were built from 1994, under the presidency of Bill Clinton, as part of three larger "operations" to taper transportation of illegal drugs manufactured in Latin America and immigration: Operation Gatekeeper in California, Operation Hold-the-Line[4] in Texas, and Operation Safeguard[5] in Arizona.

97% of border apprehensions (foreign nationals who are caught being in the U.S. illegally) by the Border Patrol in 2010 occurred at the southwest border. The number of Border Patrol apprehensions declined 61% from 1,189,000 in 2005 to 723,840 in 2008 to 463,000 in 2010. The decrease in apprehensions may be due to a number of factors, including changes in U.S. economic conditions and border enforcement efforts. Border apprehensions in 2010 were at their lowest level since 1972.[6] In December 2016 apprehensions were at 58,478, whereas in March 2017, there were 17,000 apprehensions, which was the fifth month in a row of decline.[7]

The Secure Fence Act of 2006 authorized the construction of hundreds of miles of fencing along the Mexican border. The 1,954 miles (3,145 km) border between the United States and Mexico traverses a variety of terrains, including urban areas and deserts.[8] The barrier is located on both urban and uninhabited sections of the border, areas where the most concentrated numbers of illegal crossings and drug trafficking have been observed in the past. These urban areas include San Diego, California and El Paso, Texas.

By May 2011, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported completing 649 miles (1,044 km) of fencing (99.5% of the 652 miles planned). The barrier was made up of 299 miles (481 km) of vehicle barriers and 350 miles (560 km) of pedestrian fence.[9] The fencing includes a steel fence (varying in height between 18 and 26 feet) that divides the border towns of Nogales, Arizona in the U.S. and Nogales, Sonora in Mexico.[10] A 2016 report by the Government Accountability Office confirmed that the government had completed the fence by 2015.[11] A 2017 GAO report noted: "In addition to the 654 miles of primary fencing, CBP has also deployed additional layers of pedestrian fencing behind the primary border fencing, including 37 miles of secondary fencing and 14 miles of tertiary fencing."[12]

As a result of the barrier, there has been a marked increase in the number of people trying to cross areas that have no fence, such as the Sonoran Desert and the Baboquivari Mountain in Arizona.[13] Such immigrants must cross fifty miles (80 km) of inhospitable terrain to reach the first road, which is located in the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation.[13][14]

Status

U.S. Representative Duncan Hunter, a Republican from California and the then-chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, proposed a plan to the House on November 3, 2005 calling for the construction of a reinforced fence along the entire United States–Mexican border. This would also have included a 100-yard (91 m) border zone on the U.S. side. On December 15, 2005, Congressman Hunter's amendment to the Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005 (H.R. 4437) passed in the House. This plan called for mandatory fencing along 698 miles (1,123 km) of the 1,954-mile (3,145-kilometre) border.[15] On May 17, 2006 the U.S. Senate proposed with Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006 (S. 2611) what could be 370 miles (600 km) of triple-layered fencing and a vehicle fence. Although that bill died in committee, eventually the Secure Fence Act of 2006 was passed by Congress and signed by President George W. Bush on October 26, 2006.[16]

The government of Mexico and ministers of several Latin American countries condemned the plans. Rick Perry, Governor of Texas, also expressed his opposition, saying that, instead of being closed, the border should be opened more and through technology support legal and safe migration.[17] The barrier expansion was also opposed by a unanimous vote by the Laredo, Texas City Council.[18] Laredo's Mayor, Raul G. Salinas, defended his town's people by saying that the bill, which included miles of border wall, would devastate Laredo. He stated "These are people that are sustaining our economy by forty percent, and I am gonna [sic] close the door on them and put [up] a wall? You don't do that. It's like a slap in the face." He hoped that Congress would revise the bill to better reflect the realities of life on the border.[19]

Secure Fence Act of 2006

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Secure Fence Act of 2006, signed into law on October 26, 2006, by U.S. President George W. Bush,[20] authorized and partially funded the "possible" construction of 700 miles (1,125 km) of physical fence/barriers along the Mexican border. The very broad support for the Act implied that many assurances were made by the Administration – to the Democrats, Mexico, and the pro "Comprehensive immigration reform" minority among Republicans – that Homeland Security would proceed very cautiously. Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff announced that an eight-month test of the virtual fence he favored would precede any construction of a physical barrier.

The Department of Homeland Security has a down payment of $1.2 billion marked for border security, but not specifically for the border fence.[citation needed]

As of January 2010, the fence project had been completed from San Diego, California to Yuma, Arizona.[dubious – discuss] From there it continued into Texas and consisted of a fence that was 21 feet (6.4 m) tall and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep in the ground, cemented in a 3-foot (0.91 m)-wide trench with 5,000 psi (345 bar; 352 kg/cm²) concrete. There were no fatalities during construction, but there were 4 serious injuries with multiple aggressive acts against building crews. There was one reported shooting with no injury to a crew member in the Mexicali region. All fence sections are south of the All-American Canal, and have access roads giving border guards the ability to reach any point easily, including the dunes area where a border agent was killed 3 years prior[when?] and is now sealed off.[citation needed]

The Republican Party's 2012 platform stated "The double-layered fencing on the border that was enacted by Congress in 2006, but never completed, must finally be built."[21] The Secure Fence Act's costs were estimated at $6 billion,[22] more than the Customs and Border Protection's entire annual discretionary budget of $5.6 billion.[23] The Washington Office on Latin America noted on its Border Fact Check site in 2013 that the cost of complying with the Secure Fence Act's mandate was the reason it had not been completely fulfilled.[24]

Rethinking the expansion

The Real ID Act (2005), attached a rider to a supplemental appropriations bill funding the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: "Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the Secretary of Homeland Security shall have the authority to waive all legal requirements such Secretary, in such Secretary's sole discretion, determines necessary to ensure expeditious construction of the barriers and roads."

Secretary Chertoff exercised his waiver authority on April 1, 2008 to "waive in their entirety" the Endangered Species Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Coastal Zone Management Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act to extend triple fencing through the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve near San Diego.[25]

The Real ID Act provides that the Secretary's decisions are not subject to judicial review. In June 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of a lower court upholding the waiver authority in a case filed by the Sierra Club.[citation needed] In September 2008 a federal district court judge in El Paso dismissed a similar lawsuit brought by El Paso County, Texas.[26]

By January 2009, U.S. Customs and Border Protection and Homeland Security had spent $40 million on environmental analysis and mitigation measures aimed at blunting any possible adverse impact that the fence might have on the environment. On January 16, 2009, DHS announced it was pledging an additional $50 million for that purpose, and signed an agreement with the U.S. Department of the Interior for utilization of the additional funding.[27]

Expansion freeze

On March 16, 2010, the Department of Homeland Security announced that there would be a halt to expand the "virtual fence" beyond two pilot projects in Arizona.[28]

Contractor Boeing Corporation had numerous delays and cost overruns. Boeing had initially used police dispatching software that was unable to process all of the information coming from the border. The $50 million of remaining funding would be used for mobile surveillance devices, sensors, and radios to patrol and protect the border. At the time, the Department of Homeland Security had spent $3.4 billion on border fences and had built 640 miles (1,030 km) of fences and barriers as part of the Secure Border Initiative.[28]

Local efforts

Piecemeal fencing has also been established. In 2005, under its president, Ramón H. Dovalina, Laredo Community College, located on the border, obtained a 10-foot fence built by the United States Marine Corps. The structure led to a reported decline in border crossings on to the campus[29].

Trump administration

Throughout his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump called for the construction of a much larger and fortified border wall, claiming that if elected, he would "build the wall and make Mexico pay for it." Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has said his country would not pay for the wall.[30][31][32] On January 25, 2017, the Trump administration signed Executive Order 13767, which formally directed the US government to begin attempting to construct a border wall using existing federal funding, although actual construction of a wall did not begin at this time due to the large expense and lack of clarity on how it would be paid for.[33] In March 2018 the Trump administration secured $1.6bn from Congress for projects at the border for prior designs of approximately 100 miles of new and replacement walls.[34] From December 22, 2018 to January 25, 2019, the federal government was partially shut down due to Trump's declared intention to veto any spending bill that did not include $5 billion in funding for a border wall.[35] As of February 2019 contractors are preparing to construct $600 Million[36] worth of new border barriers to replace the current barriers along the south Texas' Rio Grande Valley section of the border wall, which congress approved in March 2018.[37]

Controversy

Ineffectiveness

Research at Texas A&M University and Texas Tech University indicates that the wall, like border walls in general, is unlikely to be effective at reducing illegal immigration or movement of contraband.[38]

Divided land

Tribal lands of three indigenous nations would be divided by a proposed border fence.[39][40]

On January 27, 2008, a Native American human rights delegation in the United States, which included Margo Tamez (Lipan Apache-Jumano Apache) and Teresa Leal (Opata-Mayo) reported the removal of the official International Boundary obelisks of 1848 by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in the Las Mariposas, Sonora-Arizona sector of the Mexico–U.S. border.[41][42] The obelisks were moved southward approximately 20 m (70 ft), onto the property of private landowners in Sonora, as part of the larger project of installing the 18-foot (5.5 m) steel barrier wall.[43]

The proposed route for the border fence would divide the campus of the University of Texas at Brownsville into two parts, according to Antonio N. Zavaleta, a vice president of the university.[44] There have been campus protests against the wall by students who feel it will harm their school.[2] In August 2008, UT-Brownsville reached an agreement with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for the university to construct a portion of the fence across and adjacent to its property. The final agreement, which was filed in federal court on Aug 5 and formally signed by the Texas Southmost College Board of Trustees later that day, ended all court proceedings between UTB/TSC and DHS. On August 20, 2008, the university sent out a request for bids for the construction of a 10-foot (3.0 m) high barrier that incorporates technology security for its segment of the border fence project. The southern perimeter of the UTB/TSC campus will be part of a laboratory for testing new security technology and infrastructure combinations.[45] The border fence segment on the UTB campus was substantially completed by December 2008.[46]

Hidalgo County

In the spring of 2007 more than 25 landowners, including a corporation and a school district, from Hidalgo and Starr County in Texas refused border fence surveys, which would determine what land was eligible for building on, as an act of protest.[47]

In July 2008, Hidalgo County and Hidalgo County Drainage District No. 1 entered into an agreement with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for the construction of a project that combines the border fence with a levee to control flooding along the Rio Grande. As of September 2008, construction of two of the Hidalgo County fence segments was under way, with five more segments scheduled to be built during the fall of 2008. The Hidalgo County section of the border fence was planned to constitute 22 miles (35 km) of combined fence and levee.[48]

Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge

On August 1, 2018, the chief of the Border Patrol's Rio Grande Valley sector indicated that although Starr County was his first priority for a wall, Hidalgo County's Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge had been selected instead for initial construction, because its land was owned by the government.[49]

National Butterfly Center

The proposed border wall has been described as a "death sentence" for the American National Butterfly Center, a privately operated outdoor butterfly conservatory that maintains a significant amount of land in Mexico.[50][51][49] Filmmaker Krista Schlyer, part of an all-woman team creating a documentary film about the butterflies and the border wall, Ay Mariposa,[52] estimates that construction would put "70 percent of the preserve habitat" on the Mexican side of the border.[53] In addition to concerns about seizure of private property by the federal government,[54] Center employees have also noted the local economic impact. The Center's director has stated that "environmental tourism contributes more than $450m to Hidalgo and Starr counties."[50]

In early December 2018, a challenge to wall construction at the National Butterfly Center was rejected by the US Supreme Court. According to the San Antonio Express News, "the high court let stand an appeals ruling that lets the administration bypass 28 federal laws", including the Endangered Species Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[51]

Mexico's condemnations

In 2006, the Mexican government vigorously condemned the Secure Fence Act of 2006. Mexico has also urged the U.S. to alter its plans for expanded fences along their shared border, saying that it would damage the environment and harm wildlife.[55]

In June 2007, it was announced that a section of the barrier had been mistakenly built from 1 to 6 feet (2 meters) inside Mexican territory. This will necessitate the section being moved at an estimated cost of over $3 million (U.S.).[56]

In 2012, then presidential candidate of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto was campaigning in Tijuana at the Playas de Monumental, less than 600 yards (550 m) from the U.S.–Mexico border adjacent to Border Field State Park. In one of his speeches he criticized the U.S. government for building the barriers, and asked for them to be removed, referencing Ronald Reagan's "Tear down this wall!" speech from Berlin in 1987.[57]

Migrant deaths

Between 1994 and 2007, there were around 5,000 migrant deaths along the Mexico–United States border, according to a document created by the Human Rights National Commission of Mexico, also signed by the American Civil Liberties Union.[58] Between 43 and 61 people died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert from October 2003 to May 2004; three times that of the same period the previous year.[13] In October 2004 the Border Patrol announced that 325 people had died crossing the entire border during the previous 12 months.[59] Between 1998 and 2004, 1,954 persons are officially reported to have died along the Mexico–U.S. border. Since 2004, the bodies of 1,086 migrants have been recovered in the southern Arizona desert.[60]

U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector reported on October 15, 2008 that its agents were able to save 443 undocumented immigrants from certain death after being abandoned by their smugglers, during FY 2008, while reducing the number of deaths by 17% from 202 in FY 2007 to 167 in FY 2008. Without the efforts of these agents, hundreds more could have died in the deserts of Arizona.[61] According to the same sector, border enhancements like the wall have allowed the Tucson Sector agents to reduce the number of apprehensions at the borders by 16% compared with fiscal year 2007.[62]

On 13 December 2018, US media reported that Jakelin Caal, a 7-year-old from Guatemala, had died while in custody of US Customs.[63] The girl’s family denied she did not have enough food to eat before she died.[64]

Environmental impact

In April 2008, the Department of Homeland Security announced plans to waive more than 30 environmental and cultural laws to speed construction of the barrier. Despite claims from then Homeland Security Chief Michael Chertoff that the department would minimize the construction's impact on the environment, critics in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, asserted that the fence endangered species and fragile ecosystems along the Rio Grande. Environmentalists expressed concern about butterfly migration corridors and the future of species of local wildcats, the ocelot, the jaguarundi, and the jaguar.[65][66]

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) conducted environmental reviews of each pedestrian and vehicle fence segment covered by the waiver, and published the results of this analysis in Environmental Stewardship Plans (ESPs).[67] Although not required to by the waiver, CBP has conducted the same level of environmental analysis (in the ESPs) that would have been performed before the waiver (in the "normal" NEPA process) to evaluate potential impacts to sensitive resources in the areas where fence is being constructed.[citation needed]

ESPs completed by CBP contain extremely limited surveys of local wildlife. For example, the ESP for the border fence built in the Del Rio Sector included a single survey for wildlife completed in November 2007, and only "3 invertebrates, 1 reptile species, 2 amphibian species, 1 mammal species, and 21 bird species were recorded." The ESPs then dismiss the potential for most adverse effects on wildlife, based on sweeping generalizations and without any quantitative analysis of the risks posed by border barriers. Approximately 461 acres (187 ha) of vegetation will be cleared along the impact corridor. From the Rio Grande Valley ESP: "The impact corridor avoids known locations of individuals of Walker's manioc (Manihot walkerae) and Zapata bladderpod (Physaria thamnophila), but approaches several known locations of Texas ayenia (Ayenia limitaris). For this reason, impacts on federally listed plants are anticipated to be short-term, moderate, and adverse." This excerpt is typical of the ESPs in that the risk to endangered plants is deemed short-term without any quantitative population analysis.[citation needed]

By August 2008, more than 90% of the southern border in Arizona and New Mexico had been surveyed. In addition, 80% of the California-Mexico border has been surveyed.[68]

About 100 species of plants and animals, many already endangered, are threatened by the wall, including the jaguar, ocelot, Sonoran pronghorn, Mexican wolf, a pygmy owl, the thick-billed parrot, and the Quino checkerspot butterfly. According to Scott Egan of Rice University, a wall can create a population bottleneck, increase inbreeding, and cut off natural migration routes and range expansion.[69][70]

An initial 75-mile (121 km) wall for which U.S. funding has been requested on the nearly 2,000-mile (3,200 km) mile border would pass through the Tijuana Slough National Wildlife Refuge in California, the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge and Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge[71] in Texas, and Mexico's Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that the U.S. is bound by global treaty to protect.[72] The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) plans to build the wall using the Real ID Act to avoid the process of making environmental impact statements, a strategy devised by Michael Chertoff during the Bush administration. Reuters said, "The Real ID Act also allows the secretary of Homeland Security to exempt CBP from adhering to the Endangered Species Act", which would otherwise prohibit construction in a wildlife refuge.[73]

See also

- Mexico–United States barrier

- List of Mexico–United States border crossings

- United States Border Patrol interior checkpoints

- Build the Wall, Enforce the Law Act of 2018

- List of walls

- Open border

- Tortilla Wall

- Border barrier

- Separation barrier

- Guatemala–Mexico border

References

- ^ Garcia, Michael John (November 18, 2016). Barriers Along the U.S. Borders: Key Authorities and Requirements (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Border Fence". NOW on PBS.

- ^ U.S. Plans Border ‘Surge’ Against Any Drug Wars The New York Times, January 7, 2009.

- ^ McPhail, Weldon, Assistant Director, Administration of Justice Issues, Dennise R. Stickley, Evaluator, David P. Alexander, Social Science Analyst: Washington, DC, Appendix I:1; Michael P. Dino, Evaluator-in-Charge, James R. Russell, Evaluator: LA Regional Office, Appendix I:2; "Border Control: Revised Strategy Is Showing Some Positive Results". Subcommittee on Information, Justice, Transportation and Agriculture, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives, December 29, 1994.

- ^ Pike, John. "Operation Gatekeeper: Operation Hold-the-Line: Operation Safeguard".

- ^ Sapp, Lesley (July 2011). Apprehensions by the U.S. Border Patrol: 2005–2010. Office of Immigration Studies, United States Department of Homeland Security (Washington, D.C.) Retrieved November 18, 2011

- ^ "U.S. Homeland Security secretary has 'elbow room' on building border wall". Homeland Preparedness News. April 5, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ "THE WALL: How long is the U.S.-Mexico border?". USA TODAY. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ Robert Farley, Obama says the border fence is 'now basically complete', PolitiFact (May 16, 2011).

- ^ Peter Holley, "Trump proposes a border wall. But there already is one, and it gets climbed over", Washington Post (April 2, 2016).

- ^ Annie Linskey, In 2006, Democrats were saying 'build that fence!', Boston Globe (January 27, 2017).

- ^ GAO February 2017, p. 9.

- ^ a b c "Border Desert Proves Deadly For Mexicans". The New York Times. May 23, 2004.

- ^ One Nation, Under Fire High Country News, February 19, 2007.

- ^ "Hunter proposal for strategic border fencing passes House". 2005. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- ^ "109th Congress Public Law 367". gpo.gov. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Rechaza gobernador de Texas muro fronterizo" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ^ James Rowley, "U.S.–Mexico Border Fence Plan Will Be 'Revisited' By Congress," Bloomberg January 17, 2007.

- ^ Kahn, Carrie (July 8, 2006). "Immigration Debate Divides Laredo". NPR. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ^ "ABC News: Bush Signs U.S.–Mexico Border Fence Bill". Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2012 Republican Party Platform" (PDF). The Republican National Convention. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan (September 30, 2006). "With Senate Vote, Congress Passes Border Fence Bill". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Budget-in-Brief" (PDF). United States Department of Homeland Security. 2006.

- ^ Isaacson, Adam. "A budget-busting proposal in the Republican platform". Border Facts: Separating Rhetoric from Reality.

- ^ "Billing Code 4410-10 Department of Homeland Security" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Narco News: Border Wall Battle: Bad News vs. Good News". narconews.com.

- ^ Archibold, Randal C. (January 17, 2009). "Border Plan Will Address Harm Done at Fence Site". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Hsu, Spencer S. (March 16, 2010). "Work to cease on 'virtual fence' along U.S.–Mexico border". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Laredo border fence offers possible comparisons". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "Donald Trump: 'We will build Mexico border wall'". BBC News. January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ "How realistic is Donald Trump's Mexico wall?". BBC News. January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ "Quien se mueve sí sale en la foto". Excelsior (in Spanish). March 7, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Davis, Julie Hirschfeld (January 25, 2017). "Trump Orders Mexican Border Wall to Be Built and Is Expected to Block Syrian Refugees". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ BBC.com. January 5, 2019 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-46748492. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Text "title - Trump's wall: How much has been built so far?" ignored (help) - ^ "Government Shutdown 2018: Latest Updates & Reaction". Politico. December 27, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Spagat, Elliot; Mascaro, Lisa (March 23, 2018). "AP News Guide: Trump gets wishes on border wall – sort of". AP NEWS. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Merchant, Nomaan (February 4, 2019). "US prepares to start building portion of Texas border wall". AP NEWS. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ "Trump's border wall will not work 'no matter how high', scientists warn". The Independent. February 17, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ O'odham tell U.N. rapporteur of struggles Indian Country, October 31, 2005

- ^ As Border Crackdown Intensifies, A Tribe Is Caught in the Crossfire, Washington Post, September 15, 2006

- ^ "Nogales Residents Say US is Building Border Wall on Mexico's Land – the narcosphere". Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Monuments, Manifest Destiny, and Mexico". August 15, 2016.

- ^ "Nogales Residents Say US is Building Border Wall on Mexico's Land". Narcosphere.narconews.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Some Texans Fear Border Fence Will Sever Routine of Daily Life", New York Times, June 20, 2007

- ^ Bids Requested for Fence Upgrade The University of Texas at Brownsville and Texas Southmost College, August 20, 2008

- ^ Sieff, Kevin (December 12, 2008). "'Friendly Fence'". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Roebuck, Jeremy (March 17, 2008). "Local: Hidalgo border fence suits head to court". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Border wall in Hidalgo County moves forward Brownsville Herald, September 6, 2008

- ^ a b del Bosque, Melissa (August 4, 2017). "National Butterfly Center Founder: Trump's Border Wall Prep 'Trampling on Private Property Rights'". The Texas Observer. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Samuel (December 13, 2018). "'Death sentence': butterfly sanctuary to be bulldozed for Trump's border wall". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Foster-Frau, Silvia (December 6, 2018). "Bulldozers to soon plow through National Butterfly Center for Trump's border wall". San Antonio Express News. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ "Ay Mariposa Film". Indiegogo. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Heimbuch, Jaymi (December 11, 2018). "All-women film team takes on border wall on behalf of all at-risk wildlife". MNN – Mother Nature Network. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Guerra, Luciano (December 17, 2018). "I voted for Trump. Now his wall may destroy my butterfly paradise". Washington Post.

- ^ "US border fences 'an eco-danger'". BBC News. July 31, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Border Fence Built In Mexico By Mistake". CBS News. June 29, 2007.

- ^ "Borders | The Fence : The Semantics of a Border Barrier". apps.cndls.georgetown.edu. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ El Universal de Mexico (Spanish) Retrieved November 9, 2007

- ^ "Border deaths of illegal migrants cause concern".

- ^ New Matilda The Long Graveyard

- ^ "CBP Border Patrol Announces Fiscal Year 2008 Achievements for Tucson Sector". Archived from the original on November 30, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tucson Sector Makes Significant Gains in 2008". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "7-year-old migrant girl taken into Border Patrol custody dies of dehydration, exhaustion". Washington Post.

- ^ "7-year-old girl who crossed border with father dies in U.S. custody". NBC News. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Marosi, Richard; Gaouette, Nicole (April 2, 2008). "Border fence will skirt environmental laws". Latimes.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Border Wall Could Threaten Northern Jaguar July 5, 2017

- ^ "Environmental Stewardship Plans (ESPs) Environmental Stewardship Summary Reports (ESSRs)". U.S. Customs and Border Protection. January 31, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Customs and Border Protection". Cbp.gov. September 28, 2005. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Ruth, David (August 3, 2017). "Border wall would put more than 100 endangered species at risk, says expert". Phys.org. Science X Network. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Greenwald, Noah; et al. (May 2017). "A Wall In the Wild" (PDF). Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Barclay, Eliza; Frostenson, Sarah (July 26, 2017). "The ecological disaster that is Trump's border wall: a visual guide". Vox. Vox Media. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Uhlemann, Sarah (August 3, 2017). "Commentary: Trump's border wall endangers wildlife refuges, World Heritage sites". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Flitter, Emily (July 21, 2017). "Trump administration seeks to sidestep border wall environmental study: sources". Thomson Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved August 4, 2017.