Bangsamoro

Bangsamoro | |

|---|---|

| Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao | |

|

Left to right, top to bottom: Bulingan Falls, Lamitan, Basilan; Sulu Provincial Capitol; Panampangan Island, Sapa-sapa, Tawi-Tawi; Polloc Port, Parang, Maguindanao; Lanao Lake at Marawi City; and PC Hill, Cotabato City | |

Location in the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 7°13′N 124°15′E / 7.22°N 124.25°E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Creation plebiscite | January 21, 2019 |

| Formulation of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority | February 22, 2019 |

| Turnover of ARMM to BARMM | February 26, 2019 |

| Regional Center | To be determined |

| Government | |

| • Type | Devolved regional parliamentary government within a unitary constitutional republic |

| • Body | Bangsamoro Transition Authority |

| • Wāli | TBD |

| • Acting Chief Minister | Murad Ebrahim |

| Demonym | Bangsamoro |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (PST) |

| Provinces | |

| Cities | |

| Municipalities | 116 |

| Barangays | 2,590 |

| Cong. districts | 8 |

| Languages | |

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (Template:Lang-fil; Template:Lang-ar Munṭiqah banjisāmūrū dhātiyyah al-ḥukm), officially the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) and also known as simply as Bangsamoro, is an autonomous region within the southern Philippines.

It replaced the existing Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region was formed after voters decided to ratify the Bangsamoro Organic Law in a January 21 plebiscite. The ratification was announced on January 25, 2019, by the Commission on Elections.[1][2][3] This marks the beginning of the transition of the ARMM to the BARMM. Another plebiscite was held in nearby regions that seek to join the area on February 6, 2019.[4][5][6][7] This plebiscite saw 63 of 67 barangays in North Cotabato join Bangsamoro.[8][4]

The Bangsamoro will take the place of the ARMM as the only Muslim-majority region in the Philippines.[9]

History

Early history and arrival of Islam

For the most part of Philippines' history, the region and most of Mindanao have been a separate territory, which enabled it to develop its own culture and identity. The region has been the traditional homeland of Muslim Filipinos since the 15th century, even before the arrival of the Spanish, who began to colonize most of the Philippines in 1565.

Muslim missionaries arrived in Tawi-Tawi in 1380 and started the colonization of the area and the conversion of the native population to Islam. In 1457, the Sultanate of Sulu was founded, and not long after that, the sultanates of Maguindanao and Buayan were also established. At the time when most of the Philippines was under Spanish rule, these sultanates maintained their independence and regularly challenged Spanish domination of the Philippines by conducting raids on Spanish coastal towns in the north and repulsing repeated Spanish incursions in their territory. It was not until the last quarter of the 19th century that the Sultanate of Sulu formally recognized Spanish suzerainty, but these areas remained loosely controlled by the Spanish as their sovereignty was limited to military stations and garrisons and pockets of civilian settlements in Zamboanga and Cotabato,[10] until they had to abandon the region as a consequence of their defeat in the Spanish–American War.

Colonial Era

The Moros had a history of resistance against Spanish, American, and Japanese rule for over 400 years. The violent armed struggle against the Japanese, Filipinos, Spanish, and Americans is considered by current Moro Muslim leaders as part of the four centuries long "national liberation movement" of the Bangsamoro (Moro Nation).[11] The 400-year-long resistance against the Japanese, Americans, and Spanish by the Moro Muslims persisted and morphed into their current war for independence against the Philippine state.[12]

In 1942, during the early stages of the Pacific War of the Second World War, troops of the Japanese Imperial Forces invaded and overran Mindanao, and the native Moro Muslims waged an insurgency against the Japanese. Three years later, in 1945, combined United States and Philippine Commonwealth Army troops liberated Mindanao, and with the help of local guerrilla units, ultimately defeated the Japanese forces occupying the region.

Regional autonomous governments in Mindanao

The Philippine government and Moro rebels have been in conflict against each other for decades. In the 1970s, then-President Ferdinand Marcos started to address the issue. On December 23, 1976, the Tripoli Agreement was signed between the Philippine government and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) with the deal brokered by then-Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Under a deal an autonomous region was to be created in Mindanao.[13] The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) founded by Ustadz Salamat Hashim then splintered from the MNLF as a result of the deal.

Marcos would later implement the agreement by creating two regional autonomous governments, rather than one, in Regions 9 and 12,[13] which cover ten (instead of thirteen) provinces. This led to the collapse of the peace pact and the resumption of hostilities between the MNLF and Philippine government forces.[14][15]

ARMM and peace deal with the MILF

A plebiscite was held in 1989 for the ratification of the charter which created the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) with Zacaria Candao, a counsel of the MNLF as the first elected Regional Governor. In September 2, 1996, a final peace deal was signed between the MNLF and the Philippine government under then President Fidel Ramos. MNLF leader and founder Nur Misuari was elected regional governor three days after the agreement. In 1997 peace talks between the Philippine government and MNLF's rival group, the MILF, began.[13]

The first deal between the national government and the MILF was made in 2008; the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain. The agreement would be declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court many weeks later.[13] Under the administration of President Benigno Aquino III, two deals were agreed upon between the national government and the MILF: the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro signed on October 15, 2012 and the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro in March 27, 2014.[16][17] which include plans regarding the establishing of a new autonomous region.

Attempts to create a Bangsamoro autonomous region

In 2012, Aquino intended to establish a new autonomous political entity under the name Bangsamoro to replace the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao which he called a "failed experiment."[18] Under his administration, a draft for the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) was made but failed to get traction to become law to the Mamasapano clash of January 2015[13] which involves the killing of 44 Special Action Force (SAF) personnel by allegedly combined forces of the MILF and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) after an operation to kill Malaysian militant Zulkifli Abdhir known by the alias Marwan.[19]

Bangsamoro Organic Law and 2019 plebiscite

Under the presidency of Aquino's successor, President Rodrigo Duterte a new draft for the BBL was made and became legislated into law as the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) in 2018.[13] A plebiscite was held on January 21, 2019 to ratify the BOL with majority of ARMM's voters deciding for the ratification of the law which meant the future abolition of the ARMM and the establishment of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. Voters in Cotabato City also voted to join the new autonomous region while Isabela City which is a part of Basilan but never part of the ARMM voted against its inclusion. The Commission on Elections proclaimed that the BOL is "deemed ratified" on January 25, 2019.[20][21] In both cities the local governments were against the BOL and campaigned heavily against the law's ratification. The provincial government of Sulu, where majority voted against inclusion, was also not in favor of the law with its governor challenging the constitutionality of the law before the Supreme Court. Despite voting against inclusion, Sulu was still included in the Bangsamoro region due to rules stated in the BOL.[22][23]

In February 2019, the second round of the plebiscite was held in the province of Lanao del Norte and some towns in North Cotabato. The plebiscite resulted in the inclusion of 63 of 67 villages or barangays in the North Cotabato which participated. It also resulted in the rejection from the province of Lanao del Norte against the bid of 6 of its Muslim-majority towns to join the Bangsamoro, despite the 6 towns (Baloi, Munai, Nunungan, Pantar, Tagoloan and Tangca) opting to join the Bangsamoro by a sheer majority with one town even voting for inclusion by 100%. A major camp of the MILF was within the Muslim areas of Lanao del Norte. A security expert from the National War College in Washington noted that "fighters would surely be unhappy with the vote's result [in Lanao del Norte] and could be a threat to peace."[24][25] A Bangsamoro Transition Commission member has stated that Lanao del Norte's rejection was "anticipated" and that "there is a provision that we can provide assistance to communities. There will be an office that would be set within the office of the chief minister that will cater to that particular issue", in regard to the six towns that were not allowed by its mother province, Lanao del Norte, to join the Bangsamoro.[25]

Transition process

With the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law following a plebiscite on January 21, 2019 the abolition process of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) begins paving way for the formal creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region. Under the law a transition body, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA), is to be organized pending the election of the new region's government officials in 2022. The second part of the plebiscite held on February 6, 2019 expanded the scope of the future Bangsamoro region to include 63 barangays in North Cotabato.

It is planned that the BTA will be constituted in February 2019. It is projected that the transition body will compose of a total of 105 members (80 appointed members and 25 elected officials of the ARMM) until June 31, 2019. After that date the body will compose of only 80 members.[26] Until the BTA is constituted, Section 5 of Article XVI of the Bangsamoro Organic Law provides for the creation of a caretaker body consisting of the same 25 ARMM officials as well as the original 20 members of the Bangsamoro Transition Commission.[26]

The members of the future Bangsamoro Transition Authority are set to take their oaths on February 20, 2019 along with the ceremonial confirmation of the plebiscite results of both the January 21, and February 6, 2019 votes. The official turnover from the ARMM to the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region is scheduled to take place on February 26, 2019 which meant the full abolition of the former.[27]

Administrative divisions

Bangsamoro will consist at least 3 component cities, 116 municipalities, and 2,590 barangays. The city of Isabela despite being part of Basilan will not be under the administrative jurisdiction of the autonomous region. Likewise, 63 barangays in North Cotabato also are part of Bangsamoro despite North Cotabato and their respective parent municipalities not under the administrative jurisdiction of the autonomous region.[28]

| Province | Capital | Population (2015)[29] | Area[30] | Density | Cities | Muni. | Bgy. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | /km2 | /sq mi | |||||||||

| Basilan | Lamitan | 9.2% | 346,579 | 1,103.50 | 426.06 | 310 | 800 | 1 | 11 | 210 | ||

| Lanao del Sur | Marawi | 27.6% | 1,045,429 | 3,872.89 | 1,495.33 | 270 | 700 | 1 | 39 | 1,159 | ||

| Maguindanao | Buluan | 31.0% | 1,173,933 | 4,871.60 | 1,880.94 | 240 | 620 | 0 | 36 | 508 | ||

| Sulu | Jolo | 21.8% | 824,731 | 1,600.40 | 617.92 | 520 | 1,300 | 0 | 19 | 410 | ||

| Tawi-Tawi | Bongao | 10.3% | 390,715 | 1,087.40 | 419.85 | 360 | 930 | 0 | 11 | 203 | ||

| Cotabato City | ‡ | — | 6.6% | 299,438 | 176.00 | 67.95 | 1,700 | 4,400 | 1 | — | 37 | |

| North Cotabato barangays | ‡‡ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 63 | |

| Total | 4,080,825 | 12,711.79 | 4,908.05 | 320 | 830 | 3 | 116 | 2,590 | ||||

| ||||||||||||

| ‡‡ 67 barangays are part of the region while their parent municipalities and parent province North Cotabato are not part of Bangsamoro; Total population and area figures for the whole Bangsamoro is yet to into account of these barangays. | ||||||||||||

Government

Between the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law and the inauguration of its first permanent government in 2022, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority will head the region. After the ratification of the BOL, the Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC) begins to transition the ARMM into the BARMM.

Organizational structure

Based on the Organic Law, the autonomous Bangsamoro government system is parliamentary-democratic similar to the one practised in the United Kingdom which is based on a political party system.[31]

Ceremonial

The ceremonial head of the region is a Wali. The future Bangsamoro Parliament will select and appoint the Wali. The Wali will have ceremonial functions and powers such as moral guardianship of the territory and convocation and dissolution of its proposed legislature.[32]

Executive

The regional government will be headed by a Chief Minister. An interim Chief Minister will be appointed by the Philippine President to lead the Bangsamoro Transition Authority.

Once the Bangsamoro Parliament is created the Chief Minister will be elected by the members of the Bangsamoro Parliament. The Chief Minister of the Bangsamoro is the chief executive of the regional government, and is assisted by a cabinet not exceeding 10 members. He appoints the members of the cabinet, subject to confirmation by the Bangsamoro Parliament. He has control of all the regional executive commissions, agencies, boards, bureaus, and offices.

Cabinet

The Bangsamoro Cabinet is composed of two Deputy Chief Minister and some members of the Parliament. The Deputy Chief Minister will be nominate by the Chief Minister and elected by the members of the Parliament while the members of the cabinet will be appointed by the Chief Minister.[33]

Council of Leaders

The Coucil of Leaders advises the Chief Minister on matters of governance of the autonomous region.[33]

The council shall include:

- Chief minister

- Members of the Congress from the Bangsamoro

- Governors and mayors of chartered cities in the Bangsamoro

- Representatives of traditional leaders, non-Moro indigenous communities, women, settler communities, the Ulama, youth, and Bangsamoro communities outside the region.

- Other sector representatives subject to mechanism laid out by the parliament

Legislative

Under the Bangsamoro Organic Law, the Bangsamoro Parliament is to serve as the legislature of the autonomous region and is to compose of 80 members. It is to be led by the Chief Minister. The Wali could dissolve the parliament.

Regional ordinances are created by the Bangsamoro Parliament, composed of Assemblymen, also elected by direct vote. Regional elections are usually held one year after general elections (national and local) depending on legislation from Congress. Regional officials have a fixed term of three years, which can be extended by an act of Congress.

The Bangsamoro Transition Authority to be constituted in February 22, 2019 will have legislative powers over the region. It is to be led by an interim Chief Minister.

Judiciary

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region will have its own regional justice system which applies Shari'ah to its residents like its predecessor the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Unlike its predecessor though, the Bangsamoro will have a Shari'ah High Court to be consist of five justices including a presiding justice in addition to appellate courts, district courts, and circuit courts. Non-Muslims could also volunteer to submit themselves under the jurisdiction of Shari'ah law. The Bangsamoro justice system also recognizes traditional or tribal laws but these would only apply to disputes of indigenous peoples within the region.[34]

Relation to the central government

Bangsamoro Organic Law provides that BARMM "shall remain an integral and inseparable part of the national territory of the Republic." The President exercises general supervision over the Regional Chief Minister. The Regional Government has the power to create its own sources of revenues and to levy taxes, fees, and charges, subject to Constitutional provisions and the provisions of No. 11054.

Cultural heritage

The people of the Bangsamoro region, including Muslims and non-Muslims, have a culture that revolves around kulintang music, a specific type of gong music, found among both Muslim and non-Muslim groups of the Southern Philippines. Each ethnic group in BARMM also has their own distinct architectures, intangible heritage, and craft arts.[35][36] A fine example of a distinct architectural style in the region is the Royal Sulu architecture which was used to make the Daru Jambangan (Palace of Flowers) in Maimbung, Sulu. The palace was demolished during the American period after been heavily damaged by a typhoon in 1932, and was never rebuilt.[37][38] It used to be the largest royal palace built in the Philippines. A campaign to faithfully re-establish it in Maimbung town has been ongoing since 1933. A very small replica of the palace was made in a nearby town in the 2010s, but it was noted that the replica does not mean that the campaign to reconstruct the palace in Maimbung has stopped as the replica does not manifest the true essence of a Sulu royal palace. In 2013, Maimbung was designated as the royal capital of the former Sultanate of Sulu by one of the family claimants to the Sulu Sultanate throne where the pretenders are buried there.[39][40]

-

Marawi, Lanao del Sur

-

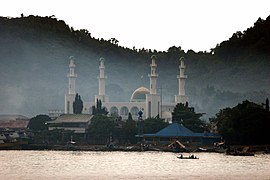

Grand mosque of Cotabato City

-

Pagoda-style mosque in Taraka, Lanao del Sur

Natural heritage

The region possesses a vast array of natural landscapes and seascapes with different types of environs. The mainland area includes the Liguasan Marsh, a proposed UNESCO tentative site, and Lake Lanao, one of the 17 most ancient lakes in the world. The Sulu archipelago region includes the Turtle Islands Wildlife Sanctuary (a UNESCO tentative site), Bongao Peak, and the Basilan Rainforest.

Proposed set-up in a federal government

The Bangsamoro Basic Law bill was considered for shelving by the 17th Congress of the Philippines. The bill was planned to be integrated to the federalism concept proposal by President Rodrigo Duterte.[41] In case the proposed federalism fails to be passed, President Duterte said that he will concede to the provisions of the bill.[42]

In January 2017, Nene Pimentel proposed in a federalism forum that the Bangsamoro state should be divided into two autonomous regions, namely, mainland Muslim Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago, as the two Muslim areas are distinct from each other in terms of culture.[43] He made the statement after going around the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, whose people told him that the Muslims of the offshore islands (Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi) do not want to be lumped together with the mainland Muslims of Mindanao as they are distinct from each other. Pimentel also noted that Shariah law could only be applied in the Bangsamoro state (composed of Autonomous Region of Mainland Bangsamoro and Autonomous Region of Sulu) if the two parties are Muslims, but if one or both parties are non-Muslims, national law will always apply.[43]

Comparisons

| Body | Bangsamoro Autonomous Region | (National Government only) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional document | ARMM Organic Act (Republic Act No. 6734) | Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (Republic Act No. 11054)[44] | Constitution of the Philippines | |

| Head of the region or territory | Regional Governor of the ARMM | Wāli | President of the Philippines | |

| Head of government | Chief Minister of the Bangsamoro | |||

| Executive | Executive Departments of the ARMM | Bangsamoro Cabinet | Executive Departments of the Philippines | |

| Legislative | Regional Legislative Assembly | Bangsamoro Parliament | Bicameral: Senate and Congress | |

| Judiciary | None (under Philippine government) | Shariah High Court (under Supreme Court) | Supreme Court | |

| Legal Supervisory or Prosecution |

None (under Philippine government) | Planned (before 2016) | Department of Justice | |

| Police Force(s) | Philippine National Police; under the National Government |

Philippine National Police | ||

| Military | Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP); under the National Government |

Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) | ||

| Currency | Philippine peso | Philippine peso | ||

| Foreign relations | None | full rights | ||

| Shariah law | Yes, for Muslims only | "Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines" issued in 1977 under Presidential Directive 1083[45] | ||

See also

- Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro

- Comprehensive Agreement on Bangsamoro

- Peace process with the Bangsamoro in the Philippines

- Federalism in the Philippines

References

- ^ Depasupil, William; TMT; Reyes, Dempsey (23 January 2019). "'Yes' vote prevails in 4 of 5 provinces". The Manila Times. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Galvez, Daphne (22 January 2019). "Zubiri: Overwhelming 'yes' vote for BOL shows Mindanao shedding its history of conflict". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Esguerra, Christian V. (25 January 2019). "New era dawns for Bangsamoro as stronger autonomy law ratified". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1082718/21-of-67-villages-in-north-cotabato-join-barmm

- ^ https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1082784/no-wins-in-13-lanao-del-norte-towns-yes-wins-in-only-9-towns

- ^ Jennings, Ralph (27 July 2018). "Historic Autonomy Deal for Philippine Muslims Takes Aim at 50 Years of Strife". Voice of America. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ Esguerra, Anthony Q. (27 July 2018). "EU expresses support for Bangsamoro Organic Law". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ https://www.rappler.com/nation/222984-plebiscite-results-number-of-barangays-cotabato-join-bangsamoro-region

- ^ Kapahi, Anushka D.; Tañada, Gabrielle. "The Bangsamoro Identity Struggle and the Bangsamoro Basic Law as the Path to Peace". Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses.

- ^ Mindanao Peace Process, Fr. Eliseo R. Mercado, Jr., OMI.

- ^ Banlaoi 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Banlaoi 2005 Archived 2016-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f Unson, John (27 January 2019). "Plebiscite in Mindanao: Will it be the last?". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Kin Wah, Chin (2004). Southeast Asian Affairs 2004. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9812302387.

- ^ Howe, Brendan M. (2014). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1409469433.

- ^ Legaspi, Amita O. (9 April 2015). "'Who is he?' Senate panel to press Iqbal on real name". GMA News. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ Regencia, Ted (25 March 2014). "Philippines prepares for historic peace deal". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ Calonzo, Andreo (7 October 2012). "Govt, MILF agree to create 'Bangsamoro' to replace ARMM". GMA News. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Orendain, Simone (28 March 2015). "Philippines, Muslim Rebels Try to Salvage Peace Pact". Voice of America. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ https://www.manilatimes.net/sulu-cities-of-isabela-cotabato-to-reject-bol/499160/

- ^ https://www.rappler.com/nation/221899-plebiscite-results-armm-votes-ratify-bangsamoro-organic-law

- ^ https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/regions/682477/sulu-voters-reject-bol/story/

- ^ https://www.rappler.com/nation/221802-plebiscite-results-sulu-votes-against-bangsamoro-law

- ^ https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/02/14/19/key-rebel-stronghold-left-out-of-bangsamoro-territory

- ^ a b https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/02/15/19/excluded-lanao-del-norte-towns-may-still-benefit-from-new-bangsamoro-region-transition-body-member

- ^ a b Arguillas, Carolyn. "Bangsamoro law ratified; how soon can transition from ARMM to BARMM begin?". MindaNews. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Arguillas, Carolyn (18 February 2019). "Bangsamoro Transition Authority to take oath Feb. 20; ARMM to BARMM turnover on Feb. 25". MindaNews. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Arguilas, Carolyn (8 February 2019). "Pikit's fate: 20 barangays remain with North Cotabato, 22 joining BARMM". Minda News. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Bangsamoro Development Plan Integrative Report, Chapter 10" (Document). 2015.

talk page.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - ^ Quintos, Patrick (25 January 2019). "After Bangsamoro Organic Law is ratified, now comes the hard part". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

The autonomous Bangsamoro government will be parliamentary-democratic, similar to the United Kingdom, and based on a political party system.

- ^ Calonzo, Andreo (10 September 2014). "PNoy personally submits draft Bangsamoro law to Congress leaders". GMA News. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b Gavilan, Jodesz (31 January 2019). "Key positions in the Bangsamoro government". Rappler. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Bicam approves creation of Shari'ah High Court in Bangsamoro". Rappler. 12 July 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Kamlian, Jamail A (1999). "Bangsamoro society and culture : a book of readings on peace and development in Southern Philippines" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|via=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Bangsamoro Development Plan Integrative Report, Chapter 11" (Document). 2015.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - ^ Selga, Miguel (1932). "The Typhoon of Jolo—Indo-China (April 29–May 5, 1932)" (Document). doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1932)60<124b:TTOJAM>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|via=ignored (help) - ^ Philippines. Weather Bureau (1932). Meteorological Bulletin. Bureau of Printing.

- ^ Whaley, Floyd (21 October 2013). "Obituary: Jamalul Kiram III / Self-proclaimed 'poorest sultan'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Whaley, Floyd (21 September 2015). "Esmail Kiram II, Self-Proclaimed Sultan of Sulu, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Diaz, Jess (22 May 2016). "No BBL: Next Congress to focus on federalism". PhilStar Global. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Duterte to concede to BBL if federalism bid fails". PhilStar Global. 10 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b Pimentel, Nene (2016). "Balancing the Distribution of Government Powers (Federalism)" (Document). pp. 54 and 63 of 130.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - ^ "DOCUMENT: Marcos submits overhauled Bangsamoro bill". Rappler. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "A Decree to Ordain and Promulgate a Code Recognizing the System of Filipino Muslim Laws, Codifying Muslim Personal Laws, and Providing for Its Administration and for Other Purposes" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help)