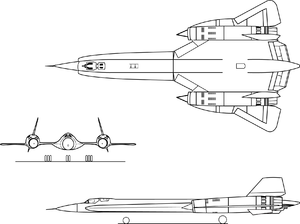

Lockheed YF-12

| YF-12 | |

|---|---|

| |

| YF-12A | |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| Designer | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 7 August 1963 |

| Status | Canceled |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NASA |

| Number built | 3 |

| Developed from | Lockheed A-12 |

The Lockheed YF-12 is an American prototype interceptor aircraft evaluated by the United States Air Force in the 1960s. The YF-12 was a twin-seat version of the secret single-seat Lockheed A-12 reconnaissance aircraft, which led to the U.S. Air Force's Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird twin-seat reconnaissance variant. The YF-12 set and held speed and altitude world records of over 2,000 miles per hour (3,200 km/h) and over 80,000 feet (24,000 m) (later surpassed by the SR-71), and is the world's largest manned interceptor to date.[1] After retirement it served as a research aircraft for NASA, which used it to develop several significant improvements in control for supersonic aircraft, including the SR-71.

Design and development

In the late 1950s, the United States Air Force (USAF) sought a replacement for its F-106 Delta Dart interceptor. As part of the Long Range Interceptor Experimental (LRI-X) program, the North American XF-108 Rapier, an interceptor with Mach 3 speed, was selected. However, the F-108 program was canceled by the Department of Defense in September 1959.[2] During this time, Lockheed's Skunk Works was developing the A-12 reconnaissance aircraft for the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) under the Oxcart program. Kelly Johnson, the head of Skunk Works, proposed to build a version of the A-12 named AF-12 by the company; the USAF ordered three AF-12s in mid-1960.[3]

The AF-12s took the seventh through ninth slots on the A-12 assembly line; these were designated as YF-12A interceptors.[4] The main changes involved modifying the A-12's nose by cutting back the chines to accommodate the huge Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire-control radar originally developed for the XF-108, and the addition of the second cockpit for a crew member to operate the fire control radar for the air-to-air missile system. The modifications changed the aircraft's aerodynamics enough to require ventral fins to be mounted under the fuselage and engine nacelles to maintain stability. The four bays previously used to house the A-12's reconnaissance equipment were converted to carry Hughes AIM-47 Falcon (GAR-9) missiles.[5] One bay was used for fire control equipment.[6]

The first YF-12A flew on 7 August 1963.[5] President Lyndon B. Johnson announced the existence of the aircraft[A][7] on 24 February 1964.[8][9] The YF-12A was announced in part to continue hiding the A-12, its still-secret ancestor; any sightings of CIA/Air Force A-12s based at Area 51 in Nevada could be attributed to the well-publicized Air Force YF-12As based at Edwards Air Force Base in California.[7]

On 14 May 1965, the Air Force placed a production order for 93 F-12Bs for its Air Defense Command (ADC).[10] However, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would not release the funding for three consecutive years due to Vietnam War costs.[10] Updated intelligence placed a lower priority on defense of the continental US, so the F-12B was deemed no longer needed. Then in January 1968, the F-12B program was officially ended.[11]

Operational history

Air Force testing

During flight tests the YF-12As set a speed record of 2,070.101 miles per hour (3,331.505 km/h) and altitude record of 80,257.86 feet (24,462.60 m), both on 1 May 1965,[8] and demonstrated promising results with its unique weapon system. Six successful firings of the AIM-47 missiles were completed. The last one was launched from the YF-12 at Mach 3.2 at an altitude of 74,000 feet (23,000 m) to a JQB-47E target drone 500 feet (150 m) off the ground.[12] One of the Air Force test pilots, Jim Irwin, would go on to become a NASA astronaut and walk on the Moon.

The program was abandoned following the cancellation of the production F-12B, but the YF-12s continued flying for many years with the USAF and with NASA as research aircraft.

NASA testing

The initial phase of the test program included objectives aimed at answering some questions about implementation of the B-1. Air Force objectives included exploration of its use in a tactical environment, and how airborne early warning and control (AWACS) would control supersonic aircraft. The Air Force portion was budgeted at US$4 million. The NASA tests would answer questions such as how engine inlet performance affected airframe and propulsion interaction, boundary layer noise, heat transfer under high Mach conditions, and altitude hold at supersonic speeds. The NASA budget for the 2.5-year program was US$14 million.[13]

The YF-12 and SR-71 originally suffered from severe control issues that affected both the engines and the physical control of the aircraft. Wind testing at NASA Dryden and YF-12 research flights developed computer systems that nearly completely solved the performance issues. Testing revealed vortices from the nose chines interfering with intake air, which lead to the development of a computer control system for the engine air bypasses. A computer system to reduce unstarts was also developed, which greatly improved stability. They also developed a flight engineering computer program called Central Airborne Performance Analyzer (CAPA) that relayed engine data to the pilots and informed them of any faults or issues with performance and indicated the severity of malfunctions.[14]

Another system called Cooperative Airframe-Propulsion Control System (CAPCS) greatly improved the control of supersonic aircraft in flight. At such high speeds even minor changes in direction caused the aircraft to change position by thousands of feet, and often had severe temperature and pressure changes. CAPCS reduced these deviations by a factor of 10. The overall improvements increased range of the SR-71 by 7 percent. [15]

Of the three YF-12As, AF Ser. No. 60-6934 was damaged beyond repair by fire at Edwards AFB during a landing mishap on 14 August 1966; its rear half was salvaged and combined with the front half of a Lockheed static test airframe to create the only SR-71C.[16][17]

YF-12A, AF Ser. No. 60-6936 was lost on 24 June 1971 due to an in-flight fire caused by a failed fuel line; both pilots ejected safely just north of Edwards AFB. YF-12A, AF Ser. No. 60-6935 is the only surviving YF-12A; it was recalled from storage in 1969 for a joint USAF/NASA investigation of supersonic cruise technology, and then flown to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio on 17 November 1979.[8]

A fourth YF-12 aircraft, the "YF-12C", was actually the second SR-71A (AF Ser. No. 61–7951). This SR-71A was re-designated as a YF-12C and given the fictitious Air Force Serial Number 60-6937 from an A-12 to maintain SR-71 secrecy. The aircraft was loaned to NASA for propulsion testing after the loss of YF-12A (AF Ser. No. 60–6936) in 1971. The YF-12C was operated by NASA until September 1978, when it was returned to the Air Force.[18]

The YF-12 had a real-field sonic-boom overpressure value between 33.5 and 52.7 N/m2 (0.7 to 1.1 lb/ft2) – below 48 was considered "low".[19]

Variants

- YF-12A

- Pre-production version. Three were built.[20]

- F-12B

- Production version of the YF-12A; canceled before production could begin.[21]

- YF-12C

- Fictitious designation for an SR-71 provided to NASA for flight testing. The YF-12 designation was used to keep SR-71 information out of the public domain.[22]

Operators

Accidents and incidents

- 24 July 1971 YF-12A 60-6936 (Article 1003) was lost in an accident near Edwards Air Force Base, California, United States.

Aircraft on display

- YF-12A

- YF-12A, AF Ser. No. 60-6935 (Article 1002) – at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio. This aircraft has small patches in its skin, on the starboard side below the cockpit. The patches cover holes caused by the "spurs" of a crewman who had to evacuate the plane after an emergency landing.[23]

- SR-71C, AF Ser. No. 61-7981 (portion of the former YF-12A AF Ser. No. 60-6934) is on display at the Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, Utah.[24]

Specifications (YF-12A)

Data from Lockheed's SR-71 'Blackbird' Family[25]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2; pilot and fire control officer (FCO)

- Aspect ratio: 1.7

Performance

- Thrust/weight: 0.44

Armament

- Missiles: 3× Hughes AIM-47A air-to-air missiles located internally in fuselage bays

Avionics

- Hughes AN/ASG-18 look-down/shoot-down fire control radar

See also

Related development

Related lists

References

Notes

- ^ Johnson's speech named the plane A-11, the name for the two-seat design.

Citations

- ^ Pace, Steve (1995). X-Planes at Edwards. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-61060786-5.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d Green and Swanborough, 1988, p. 350.

- ^ "Hughes AIM-47 Falcon". Designation systems.

- ^ a b McIninch 1996, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Air Force Museum Foundation, 1983, p. 133.

- ^ McIninch 1996, p. 14.

- ^ a b Pace 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Donald 2003, pp. 148, 150.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Drendel 1982, p. 6.

- ^ https://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/about/Organizations/Technology/Facts/TF-2004-17-DFRC.html

- ^ https://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/about/Organizations/Technology/Facts/TF-2004-17-DFRC.html

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 62, 75.

- ^ Pace 2004, pp. 109–10.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 49–55.

- ^ Dugan, James F. Jr. "Preliminary study of supersonic-transport configurations with low values of sonic boom", p. 18. NASA Lewis Research Center, March 1973. Retrieved: March 2012.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "YF-12A/60-6935." Archived 4 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 16 April 2013.

- ^ "YF-12A/60-6934." Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Hill Aerospace Museum. Retrieved: 16 April 2013.

- ^ Goodall and Miller, 2002.

Bibliography

- Air Force Museum Foundation Inc. US Air Force Museum. Dayton, Ohio: Wright-Patterson AFB, 1983.

- Donald, David, ed. "Lockheed's Blackbirds: A-12, YF-12 and SR-71". Black Jets. AIRtime, 2003. ISBN 1-880588-67-6.

- Drendel, Lou. SR-71 Blackbird in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1982, ISBN 0-89747-136-9.

- Goodall, James and Jay Miller. Lockheed's SR-71 'Blackbird' Family. Hinchley, England: Midland Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1-85780-138-5.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Complete Book of Fighters. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1988, ISBN 0-7607-0904-1.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Lockheed Secret Projects: Inside the Skunk Works. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7603-0914-8.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis. Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. Minnesota, US: Specialty Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Landis, Tony R. and Dennis R. Jenkins. Lockheed Blackbirds. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, revised ed., 2005, ISBN 1-58007-086-8.

- McIninch, Thomas. "The Oxcart story". Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 2 July 1996. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- Pace, Steve. Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. Swindon: Crowood Press, 2004, ISBN 1-86126-697-9.

External links

- Mach 3+: NASA/USAF YF-12 Flight Research, 1969–1979 by Peter W. Merlin (PDF book)

- YF-12A Flight Manual and YF-12A #60-6935 Photos on SR-71.org

- YF-12 fact sheet on USAF Museum site

- Where are they now? Map of the location of every Blackbird

- USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers for 1960, including all A-12s, YF-12As, and M-21s

- NASA videos: Take-off, Mid-air Refueling