Extinct in the wild

| Conservation status |

|---|

| Extinct |

| Threatened |

| Lower Risk |

| Other categories |

| Related topics |

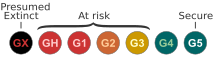

Comparison of Red List classes above and NatureServe status below  |

A species that is extinct in the wild (EW) is one that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as known only by living members kept in captivity or as a naturalized population outside its historic range due to massive habitat loss.[1]

Examples

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

Examples of species and subspecies that are extinct in the wild include:

- Alagoas curassow (extinct in the wild since 1988)

- Beloribitsa

- Black soft-shell turtle (extinct in the wild since 2017)

- Cachorrito de charco palmal

- Escarpment cycad (extinct in the wild since 2006)[2]

- Franklinia

- Golden skiffia

- Guam kingfisher (extinct in the wild since 1986)

- Guam rail (extinct in the wild since the 1980s) (released into the wild)

- Hawaiian crow or ʻalalā (extinct in the wild since 2002) (released into the wild; if the group maintains long term viability the IUCN may downgrade from extinct in the wild)

- Kihansi spray toad (extinct in the wild since 2009)

- Oahu deceptor bush cricket

- Pedder galaxias

- Père David's deer (extinct in the wild since 2008)

- Scimitar oryx (extinct in the wild since 1998; a small herd was successfully released into the wild in Chad in 2016. If the herd maintains long term viability the IUCN may downgrade from extinct in the Wild to Critically Endangered)

- Socorro dove (extinct in the wild since 1972)

- Socorro isopod (extinct in the wild since 1988)

- South China tiger (possibly extinct in the wild since the 1970s)

- Spix's macaw (possibly extinct in the wild since 2016)

- Wyoming toad (considered extinct in the wild since 1991, though almost 900 have been released into the wild since. The IUCN is anticipated[by whom?] to downgrade their condition from extinct in the wild)

The Pinta Island tortoise (Geochelone nigra abingdoni) had only one living individual, named Lonesome George, until his death in June 2012.[3] The tortoise was believed to be extinct in the mid-20th century, until Hungarian malacologist József Vágvölgyi spotted Lonesome George on the Galapagos island of Pinta on 1 December 1971. Since then, Lonesome George has been a powerful symbol for conservation efforts in general and for the Galapagos Islands in particular.[4] With his death on 24 June 2012, the subspecies is again believed to be extinct.[5] With the discovery of 17 hybrid Pinta tortoises located at nearby Wolf Volcano a plan has been made to attempt to breed the subspecies back into a pure state.[6]

Not all species that are extinct in the wild are rare. For example, Ameca splendens, though extinct in the wild,[7] was a popular fish among aquarists for some time, but hobbyist stocks have declined quite a lot more recently, placing its survival in jeopardy.[8] However, the ultimate purpose of preserving biodiversity is to maintain ecological function. When a species exists only in captivity, it is ecologically extinct.

Reintroduction

Reintroduction is the deliberate release of species into the wild, from captivity or relocated from other areas where the species survives. This may be an option for certain species that are endangered or extinct in the wild. However, it may be difficult to reintroduce EW species into the wild, even if their natural habitats were restored, because survival techniques, which are often passed from parents to offspring during parenting, may be lost. While conservation efforts may preserve some of the genetics of a species, the species may never fully recover due to the loss of the natural memetics of the species.

An example of a successful reintroduction of an EW species is Przewalski's horse, which as of 2018 is considered to be an Endangered species, following reintroduction started in the 1990s.[9]

See also

- IUCN Red List extinct in the wild species for a list by taxonomy

- Category:IUCN Red List extinct in the wild species for an alphabetical list

- Extinction

Notes and references

- ^ IUCN, 2001 IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1 p.14 Last visited: 30 May 2010.

- ^ Donaldson, J.S. (2010). "Encephalartos brevifoliolatus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010. IUCN: e.T41882A10566751. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T41882A10566751.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Gardner, Simon (6 February 2001). "Lonesome George faces own Galapagos tortoise curse". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nicholls, H (2006). Lonesome George: The Life and Loves of a Conservation Icon. London: Macmillan Science. ISBN 1-4039-4576-4.

- ^ "Last Pinta giant tortoise Lonesome George dies". BBC News. 24 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Not so Lonesome (George) after all: Scientists believe they can resurrect extinct species of famous tortoise by cross-breeding". The Daily Mail. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Contreras-Balderas, S. & Almada-Villela, P. (1996). "Ameca splendens". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. IUCN: e.T1117A3259262. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T1117A3259262.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kelley, J.L.; Magurran, A.E. & Macías García, C. (2006): Captive breeding promotes aggression in an endangered Mexican fish. Biological Conservation 133(2): 169–177. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.06.002 (HTML abstract)

- ^ "An extraordinary return from the brink of extinction for worlds last wild horse". 12 February 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

External links

- List of Extinct in the Wild species as identified by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species