Australian Capital Territory

Template:Infobox Australia state or territory

The Australian Capital Territory, formerly known as the Federal Capital Territory until 1938 and commonly referred to as the ACT, is a federal territory of Australia containing the Australian capital city of Canberra and some surrounding townships. It is located in the south-east of the country and enclaved within the state of New South Wales. Founded after federation as the seat of government for the new nation, all important institutions of the Australian federal government are centred in the Territory.

On 1 January 1901, federation of the colonies of Australia was achieved. Section 125 of the new Australian Constitution provided that land, situated in New South Wales and at least 100 miles (160 km) from Sydney, would be ceded to the new federal government. Following discussion and exploration of various areas within New South Wales, the Seat of Government Act 1908 was passed in 1908 which specified a capital in the Yass-Canberra region. The territory was transferred to the Commonwealth by New South Wales in 1911, two years prior to the capital city being founded and formally named as Canberra in 1913.

While the overwhelming majority of the population reside in the city of Canberra in the ACT's north-east, the Territory also includes some surrounding townships such as Williamsdale, Naas, Uriarra, Tharwa and Hall. The ACT also includes the Namadgi National Park which comprises the majority of land area of the Territory. Despite a common misconception, the Jervis Bay Territory is not part of the ACT although the laws of the Australian Capital Territory apply as if Jervis Bay did form part of the ACT.[1] The Territory has a relatively dry, contintental climate experiencing warm to hot summers and cool to cold winters.

The Australian Capital Territory is home to many important institutions of the federal government, national monuments and museums. This includes the Parliament of Australia, the High Court of Australia, the Australian Defence Force Academy and the Australian War Memorial. It also hosts the majority of foreign embassies in Australia as well as regional headquarters of many international organisations, not-for-profit groups, lobbying groups and professional associations. Several major universities also have campuses in the ACT including the Australian National University, the University of Canberra, the University of New South Wales, Charles Sturt University and the Australian Catholic University.

A locally elected legislative assembly has governed the Territory since 1988. However, the Commonwealth maintains authority over the Territory and may overturn local laws. It still maintains control over the area known as the Parliamentary Triangle through the National Capital Authority. Residents of the Territory elect three members to the House of Representatives and two Senators to the Australian Senate.

With 419,200 residents, the Australian Capital Territory is second smallest mainland state or territory by population. At the 2016 census, the median weekly income for people in the Territory aged over 15 was $998 and higher than the national average of $662.[2] The average level of degree qualification in the ACT is also higher than the national average. Within the ACT, 37.1% of the population hold a bachelor degree level or above education compared to the national figure of 20%.[2]

History

The first inhabitants

Indigenous Australian peoples have long inhabited the area.[3] Evidence indicates habitation dating back at least 21,000 years. It is possible that the area was inhabited for considerably longer, with evidence of an Aboriginal presence in south-western New South Wales dating back around 40,000–62,000 years. The principal group occupying the region were the Ngunnawal people.[4]

European exploration

Following European settlement, the growth of the new colony of New South Wales led to an increasing demand for arable land.[4] Governor Lachlan Macquarie supported expeditions to open up new lands to the south of Sydney.[5]

The 1820s saw further exploration in the Canberra area associated with the construction of a road from Sydney to the Goulburn plains. While working on the project, Charles Throsby learned of a nearby lake and river from the local Indigenous peoples and he accordingly sent Wild to lead a small party to investigate the site. The search was unsuccessful, but they did discover the Yass River and it is surmised that they would have set foot on part of the future territory.[6]

A second expedition was mounted shortly thereafter and they became the first Europeans to camp at the Molonglo (Ngambri) and Queanbeyan (Jullergung) Rivers.[3] However, they failed to find the Murrumbidgee River.[6] The issue of the Murrumbidgee was solved in 1821 when Charles Throsby mounted a third expedition and successfully reached the watercourse, on the way providing the first detailed account of the land where Canberra now resides.[6]

The last expedition in the region prior to settlement was undertaken by Allan Cunningham in 1824.[3] He reported that the region was suitable for grazing and the settlement of the Limestone Plains followed immediately thereafter.[7]

Early settlement

The first land grant in the region was made to Joshua John Moore in 1823 and European settlement in the area began in 1824 with the construction of a homestead by his stockmen on what is now the Acton Peninsula.[5] Moore formally purchased the site in 1826 and named the property Canberry or Canberra.[3]

A significant influx of population and economic activity occurred around the 1850s goldrushes.[8] The goldrushes prompted the establishment of communication between Sydney and the region by way of the Cobb & Co coaches, which transported mail and passengers.[9] The first post offices opened in Ginninderra in 1859 and at Lanyon in 1860.[5]

During colonial times, the European communities of Ginninderra, Molonglo and Tuggeranong settled and farmed the surrounding land. The region was also called the Queanbeyan-Yass district, after the two largest towns in the area. The villages of Ginninderra and Tharwa developed to service the local agrarian communities.

During the first 20 years of settlement, there was only limited contact between the settlers and Aboriginal people. Over the succeeding years, the Ngunnawal and other local indigenous people effectively ceased to exist as cohesive and independent communities adhering to their traditional ways of life.[5] Those who had not succumbed to disease and other predations either dispersed to the local settlements or were relocated to more distant Aboriginal reserves set up by the New South Wales government in the latter part of the 19th century.

Creation of the territory

In 1898, a referendum on a proposed Constitution was held in four of the colonies – New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Although the referendum achieved a majority in all four colonies, the New South Wales referendum failed to gain the minimum number of votes needed for the bill to pass. Following this result, a meeting of the four Premiers in 1898 heard from George Reid, the Premier of New South Wales, who argued that locating the future capital in New South Wales would be sufficient to ensure the passage of the Bill. The 1899 referendum on this revised bill was successful and passed with sufficient numbers.[10] Section 125 of the Australian Constitution thus provided that, following Federation in 1901, land would be ceded freely to the new Federal Government.

This, however, left open the question of where to locate the capital. In 1906 and after significant deliberations, New South Wales agreed to cede sufficient land on the condition that it was in the Yass-Canberra region,[3] this site being closer to Sydney.[11] Initially, Dalgety remained at the forefront, but Yass-Canberra prevailed after voting by federal representatives.[6] The Seat of Government Act 1908 was passed in 1908, which repealed the 1904 Act and specified a capital in the Yass-Canberra region.[3][12] Government surveyor Charles Scrivener was deployed to the region in the same year in order to map out a specific site and, after an extensive search, settled upon the present location.

The territory was transferred to the Commonwealth by New South Wales in 1911, two years prior to the naming of Canberra as the national capital in 1913.

Development throughout 20th century

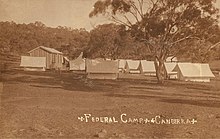

In 1911, an international competition to design the future capital was held, which was won by the Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin in 1912.[5] The official naming of Canberra occurred on 12 March 1913 and construction began immediately.[5]

After Griffin's departure following difficulty in implementing his project,[13] the Federal Capital Advisory Committee was established in 1920 to advise the government of the construction efforts.[3] The Committee had limited success meeting its goals. However, the chairman, John Sulman, was instrumental in applying the ideas of the garden city movement to Griffin's plan. The Committee was replaced in 1925 by the Federal Capital Commission.[3]

In 1930, the ACT Advisory Council was established to advise the Minister for Territories on the community's concerns. In 1934, Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory was established.

From 1938 to 1957, the National Capital Planning and Development Committee continued to plan the further expansion of Canberra. However, the National Capital Planning and Development Committee did not have executive power, and decisions were made on the development of Canberra without the Committee's consultation.[9] During this time, Prime Minister Robert Menzies regarded the state of the national capital as an embarrassment.[14]

After World War II, there was a shortage of housing and office space in Canberra.[15] A Senate Select Committee hearing was held in 1954 to address its development requirements. This Committee recommended the creation of a single planning body with executive power. Consequently, the National Capital Planning and Development Committee was replaced by the National Capital Development Commission in 1957.[16] The National Capital Development Commission ended four decades of disputes over the shape and design of Lake Burley Griffin and construction was completed in 1964 after four years of work. The completion of the centrepiece of Griffin's design finally the laid the platform for the development of Griffin's Parliamentary Triangle.[14]

Self-government

In 1988, the new Minister for the Australian Capital Territory Gary Punch received a report recommending the abolition of the National Capital Development Commission and the formation of a locally elected government. Punch recommended that the Hawke government accept the report's recommendations and subsequently Clyde Holding introduced legislation to grant self-government to the Territory in October 1988.[17]

The enactment on 6 December 1988 of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 established the framework for self-government.[18] The first election for the 17-member Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly was held on 4 March 1989.[19]

The initial years of self-government were difficult and unstable.[20] A majority of ACT residents had opposed self-government and had it imposed upon them by the federal parliament. At the first election, 4 of the 17 seats were won by anti-self-government single-issue parties due to a protest vote by disgruntled territorians and a total of 8 were won by minor parties and independents.[20]

In 1992, Labor won eight seats and the minor parties and independents won only three. Stability increased, and in 1995, Kate Carnell became the first elected Liberal chief minister. In 1998, Carnell became the first chief minister to be re-elected.

Geography

The Australian Capital Territory is the smallest mainland territory (aside from the Jervis Bay Territory) and covers a total land area of 2,280 square kilometres (560,000 acres).

It is bounded by the Goulburn-Cooma railway line in the east, the watershed of Naas Creek in the south, the watershed of the Cotter River in the west and the watershed of the Molonglo River in the north-east. These boundaries were set to give the ACT an adequate water supply.[21] The ACT extends about 88.5 kilometres (55.0 mi) North-South between 35-36S and 57.5 kilometres (35.7 mi) West-East at around 149.6E, although the city area of Canberra occupies the north-central part of this area.

Apart from the city of Canberra, the Australian Capital Territory also contains agricultural land (sheep, dairy cattle, vineyards and small amounts of crops) and a large area of national park (Namadgi National Park), much of it mountainous and forested. Small townships and communities located within the ACT include Williamsdale, Naas, Uriarra, Tharwa and Hall.

Tidbinbilla is a locality to the south-west of Canberra that features the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve and the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, operated by the United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of its Deep Space Network.

There are a large range of mountains, rivers and creeks throughout the Territory and are largely contained within the Namadgi National Park. These include the Naas and Murrumbidgee Rivers.

Climate

The Territory has a relatively dry, contintental climate experiencing warm to hot summers and cool to cold winters.[22] Under Köppen-Geiger classification, the Territory has an oceanic climate (Cfb).[23]

January is the hottest month with an average high of 27.7 °C (81.9 °F).[22] July is the coldest month when the average high drops to 11.2 °C (52.2 °F).[22] The highest maximum temperature recorded in the Territory was 42.2 °C (108.0 °F) on 1 February 1968.[22] The lowest minimum temperature was −10.0 °C (14.0 °F) on 11 July 1971.[22]

Rainfall varies significantly across the Territory.[22] Much higher rainfall occurs in the mountains to the west of Canberra compared to the east.[22] The mountains act as a barrier during winter with the city receiving less rainfall.[22] Average annual rainfall in the Territory is 629 millimetres (24.8 in) and there is an average of 108 rain days annually.[22] The wettest month is October with an average rainfall of 65.3 millimetres (2.57 in) and the driest month is June with an average of 39.6 millimetres (1.56 in).[22]

Frost is common in the winter months. Snow is rare in Canberra's city centre, but the surrounding areas get annual snowfall through winter and often the snow-capped mountains can be seen from the city. The last significant snowfall in the city centre was in 1968.[22]

| Climate data for Canberra Airport, ACT (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1939–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.6 (106.9) |

42.2 (108.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.2 (102.6) |

42.2 (108.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.5 (2.30) |

56.4 (2.22) |

50.7 (2.00) |

46.0 (1.81) |

44.4 (1.75) |

40.4 (1.59) |

41.4 (1.63) |

46.2 (1.82) |

52.0 (2.05) |

62.4 (2.46) |

64.4 (2.54) |

53.2 (2.09) |

615.2 (24.22) |

| Average precipitation days | 7.3 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 7.7 | 106.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 294.5 | 254.3 | 251.1 | 219.0 | 186.0 | 156.0 | 179.8 | 217.0 | 231.0 | 266.6 | 267.0 | 291.4 | 2,813.7 |

| Source 1: Climate averages for Canberra Airport Comparison (1939–2010)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Special climate statements and climate summaries for more recent extremes[25] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The environments range from alpine area on the higher mountains, to sclerophyll forest and to woodland. Much of the ACT has been cleared for grazing and is also burnt off by bushfires several times per century. The kinds of plants can be grouped into vascular plants, that include gymnosperms, flowering plants, and ferns, as well as bryophytes, lichens, fungi and freshwater algae. Four flowering plants are endemic to the ACT. Several lichens are unique to the Territory. Most plants in the ACT are characteristic of the Flora of Australia and include well known plants such as Grevillea, Eucalyptus trees and kangaroo grass.

The native forest in the Canberra region was almost wholly eucalypt species and provided a resource for fuel and domestic purposes. By the early 1960s, logging had depleted the eucalypt, and concern about water quality led to the forests being closed. Interest in forestry began in 1915 with trials of a number of species including Pinus radiata on the slopes of Mount Stromlo. Since then, plantations have been expanded, with the benefit of reducing erosion in the Cotter catchment, and the forests are also popular recreation areas.[26]

The fauna of the Territory includes representatives from most major Australian animal groups. This includes kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, platypus, echidna, emu, kookaburras and dragon lizards.

Geology

Notable geological formations in the Australian Capital Territory include the Canberra Formation, the Pittman Formation, Black Mountain Sandstone and State Circle Shale.

In the 1840s fossils of brachiopods and trilobites from the Silurian period were discovered at Woolshed Creek near Duntroon. At the time, these were the oldest fossils discovered in Australia, though this record has now been far surpassed.[27] Other specific geological places of interest include the State Circle cutting and the Deakin anticline.[28][29]

The oldest rocks in the ACT date from the Ordovician around 480 million years ago. During this period the region along with most of Eastern Australia was part of the ocean floor; formations from this period include the Black Mountain Sandstone formation and the Pittman Formation consisting largely of quartz-rich sandstone, siltstone and shale. These formations became exposed when the ocean floor was raised by a major volcanic activity in the Devonian forming much of the east coast of Australia.

Government and politics

Territory government

The ACT has internal self-government, but Australia's Constitution does not afford the territory government the full legislative independence provided to Australian states. Laws are made in a 25-member Legislative Assembly that combines both state and local government functions (prior to 2016, the Assembly was made up of 17 members).[30][31]

Members of the Legislative Assembly are elected via the Hare Clarke system.[32]

The executive of the Australian Capital Territory are the Chief Minister and such other Ministers as are appointed by the Chief Minister, also known as the ACT Government.[33] The ACT Chief Minister (currently Andrew Barr, Labor) is elected by members of the ACT Legislative Assembly. The Chief Minister represents the ACT Government as a member of the Council of Australian Governments.[34]

Unlike other self-governing Australian territories (for example, the Northern Territory), the ACT does not have an Administrator.[35] The Crown is represented by the Australian Governor-General in the government of the ACT. Until 4 December 2011, the decisions of the assembly could be overruled by the Governor-General (effectively by the national government) under section 35 of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988, although the federal parliament voted in 2011 to abolish this veto power, instead requiring a majority of both houses of the federal parliament to override an enactment of the ACT.[36][37] The Chief Minister performs many of the roles that a state governor normally holds in the context of a state; however, the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly gazettes the laws and summons meetings of the Assembly.

Judiciary and policing

The court system of the Territory consists of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory, the Magistrates Court of the Australian Capital Territory and the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal. It is unique in that the Territory does not have an intermediary court like other mainland states and territories; there is only the superior court and a court of summary jurisdiction. As of April 2019[update] the Chief Justice is Helen Murrell and the current Chief Magistrate is Lorraine Walker.

ACT Policing is responsible for providing policing services to the ACT. Canberra had the lowest rate of crime of any capital city in Australia as of February 2019[update].[38]

Federal representation

In Australia's Federal Parliament, the ACT is represented by four federal members: two members of the House of Representatives represent the Division of Fenner and the Division of Canberra and it is one of only two territories to be represented in the Senate, with two Senators (the other being the Northern Territory). The Member for Fenner and the ACT Senators also represent the constituents of the Jervis Bay Territory. An additional electorate will be added at the 2019 election following a redistribution by the Australian Electoral Commission.

Jervis Bay Territory

In 1915, the Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915 created the Jervis Bay Territory as an annexe to the Federal Capital Territory. While the Act's use of the language of "annexed" is sometimes interpreted as implying that the Jervis Bay Territory was to form part of the Federal Capital Territory, the accepted legal position is that it has been a legally distinct territory from its creation despite being subject to ACT law and, prior to ACT self-government in 1988, being administratively treated as part of the ACT.[39]

In 1988, when the ACT gained self-government, Jervis Bay was formally pronounced as a separate territory administered by the Commonwealth known as the Jervis Bay Territory. However, the laws of the ACT continue to apply to the Jervis Bay Territory.[1] Magistrates from the ACT regularly travel to the Jervis Bay Territory to conduct court.[40]

Another occasional misconception is that the ACT retains a small area of territory on the coast on the Beecroft Peninsula, consisting of a strip of coastline around the northern headland of Jervis Bay. While the land is owned by the Commonwealth Government, that area itself is still considered to be under the jurisdiction of New South Wales government, not a separate territory nor a part of the ACT.[41]

Demographics

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates that the population of the Territory was 419,200 on 31 March 2019.[42] The population is projected to reach to approximately 700,000 by 2058.[43]

The overwhelming majority of the population reside in the city of Canberra.[42]

At the 2016 census, the median weekly income for people in the Territory aged over 15 was $998 while the national average was $662.[2]

The average level of degree qualification in the ACT is higher than the national average. Within the ACT, 37.1% of the population hold a bachelor degree level or above education compared to the national figure of 20%.[2]

City and townships

The Australian Capital Territory consists of the city of Canberra and some surrounding townships including Williamsdale, Naas, Uriarra, Tharwa and Hall.

The urban areas of Canberra are organised into a hierarchy of districts, town centres, group centres, local suburbs as well as other industrial areas and villages. There are seven districts (with an eighth currently under construction), each of which is divided into smaller suburbs, and most of which have a town centre which is the focus of commercial and social activities. The districts were settled in the following chronological order:

- North Canberra: mostly settled in the 1920s and '30s, with expansion up to the 1960s, now 14 suburbs;

- South Canberra: settled from the 1920s to '60s, 13 suburbs;

- Woden Valley: first settled in 1963, 12 suburbs;

- Belconnen: first settled in 1967, 25 suburbs;

- Weston Creek: settled in 1969, 8 suburbs;

- Tuggeranong: settled in 1974, 19 suburbs;

- Gungahlin: settled in the early 1990s, 18 suburbs although only 15 are developed or under development;

- Molonglo Valley: first suburbs currently under construction.

The North and South Canberra districts are substantially based on Walter Burley Griffin's designs.[44] In 1967, the then National Capital Development Commission adopted the "Y Plan" which laid out future urban development in Canberra around a series of central shopping and commercial area known as the 'town centres' linked by freeways, the layout of which roughly resembled the shape of the letter Y,[45] with Tuggeranong at the base of the Y and Belconnen and Gungahlin located at the ends of the arms of the Y.[45]

Languages

In the Territory, 72.7% of people only spoke English at home.[2] Other languages spoken at home included Mandarin (3.1%), Vietnamese (1.1%), Cantonese (1.0%), Hindi (0.9%) and Spanish (0.8%).[2]

Ethnicity

68.0% of people residing in the ACT were born in Australia.[2] The most common countries of birth were England (3.2%), China excluding SARs and Taiwan (2.9%), India (2.6%), New Zealand (1.2%) and Philippines (1.0%).[2]

The most common ancestries in the Australian Capital Territory as reported in 2016 census were English (23.8%), Australian (23.0%), Irish (9.3%), Scottish (7.3%) and Chinese (4.1%).[2]

Religion

The most common responses in the 2016 census for religion in the Territory were No Religion (36.2%), Catholic (22.3%), Anglican (10.8%), Not stated (9.2%) and Hinduism (2.6%).[2] In Australian Capital Territory, Christianity was the largest religious group reported overall (49.9%).[2]

Culture

Education

Almost all educational institutions in the Australian Capital Territory are located within Canberra. The ACT public education system schooling is normally split up into Pre-School, Primary School (K-6), High School (7–10) and College (11–12) followed by studies at university or CIT (Canberra Institute of Technology). Many private high schools include years 11 and 12 and are referred to as colleges. Children are required to attend school until they turn 17 under the ACT Government's "Learn or Earn" policy.[46]

In February 2004 there were 140 public and non-governmental schools in ACT; 96 were operated by the Government and 44 are non-Government.[47] In 2005, there were 60,275 students in the ACT school system. 59.3% of the students were enrolled in government schools with the remaining 40.7% in non-government schools. There were 30,995 students in primary school, 19,211 in high school, 9,429 in college and a further 340 in special schools.[48]

As of May 2004, 30% of people in the ACT aged 15–64 had a level of educational attainment equal to at least a bachelor's degree, significantly higher than the national average of 19%.[49] The two main tertiary institutions are the Australian National University (ANU) in Acton and the University of Canberra (UC) in Bruce. There are also two religious university campuses in Canberra: Signadou is a campus of the Australian Catholic University and St Mark's Theological College is a campus of Charles Sturt University. Tertiary level vocational education is also available through the multi-campus Canberra Institute of Technology.

The Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) and the Royal Military College, Duntroon (RMC) are in the suburb of Campbell in Canberra's inner northeast. ADFA teaches military undergraduates and postgraduates and is officially a campus of the University of New South Wales while Duntroon provides Australian Army Officer training.

The Academy of Interactive Entertainment (AIE) offers courses in computer game development and 3D animation.

Sport

The Australian Capital Territory is home to a number of major professional sports league franchise teams including the Canberra Raiders (rugby league), the Brumbies (rugby union), the Canberra Capitals (basketball).

The Greater Western Sydney Giants (Australian rules football) play three regular season matches a year and one pre-season match in Canberra at Manuka Oval.

The Prime Minister's XI (cricket), started by Robert Menzies in the 1950s andrevived by Bob Hawke in 1984, has been played every year at Manuka Oval against an overseas touring team.

Arts and entertainment

The Territory is home to many national monuments and institutions such as the Australian War Memorial, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Library,[50] the National Archives,[51] the Australian Academy of Science,[52] the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Museum.[50] Many Commonwealth government buildings in Canberra are open to the public, including Parliament House, the High Court and the Royal Australian Mint.[53][54][55]

Lake Burley Griffin is the site of the Captain James Cook Memorial and the National Carillon.[50] Other sites of interest include the Telstra Tower, the Australian National Botanic Gardens, the National Zoo and Aquarium, the National Dinosaur Museum and Questacon – the National Science and Technology Centre.[50][56]

The Canberra Museum and Gallery in the city is a repository of local history and art, housing a permanent collection and visiting exhibitions.[58] Several historic homes are open to the public: Lanyon and Tuggeranong Homesteads in the Tuggeranong Valley,[59][60] Mugga-Mugga in Symonston,[61] and Blundells' Cottage in Parkes all display the lifestyle of the early European settlers.[62] Calthorpes' House in Red Hill is a well-preserved example of a 1920s house from Canberra's very early days.[63]

Canberra has many venues for live music and theatre: the Canberra Theatre and Playhouse which hosts many major concerts and productions;[64] and Llewellyn Hall (within the ANU School of Music), a world-class concert hall are two of the most notable.[65] The Albert Hall was Canberra's first performing arts venue, opened in 1928. It was the original performance venue for theatre groups such as the Canberra Repertory Society.[66]

There are numerous bars and nightclubs which also offer live entertainment, particularly concentrated in the areas of Dickson, Kingston and the city.[67] Most town centres have facilities for a community theatre and a cinema, and they all have a library.[68] Popular cultural events include the National Folk Festival, the Royal Canberra Show, the Summernats car festival, Enlighten festival and the National Multicultural Festival in February.[69]

Media

Canberra and the Territory have a daily newspaper, The Canberra Times, which was established in 1926.[70][71] There are also several free weekly publications, including news magazines CityNews and Canberra Weekly.

There are a number of AM and FM stations broadcasting throughout the ACT (AM/FM Listing). The main commercial operators are the Capital Radio Network (2CA and 2CC), and Austereo/ARN (104.7 and Mix 106.3). There are also several community operated stations as well as the local and national stations of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

A DAB+ digital radio trial is also in operation, it simulcasts some of the AM/FM stations, and also provides several digital only stations (DAB+ Trial Listing).

Five free-to-air television stations service the Territory:

- ABC Canberra (ABC)

- SBS New South Wales (SBS)

- Win Television Southern NSW & ACT (WIN) – Network Ten affiliate

- Prime7 Southern NSW & ACT (CBN) – Seven Network affiliate

- Southern Cross Nine Southern NSW & ACT (CTC) – Nine Network affiliate

Each station broadcasts a primary channel and several multichannels.

Pay television services are available from Foxtel (via satellite) and telecommunications company TransACT (via cable).[72]

Infrastructure

Health

The Australian Capital Territory has two large public hospitals both located in Canberra: the approximately 600-bed Canberra Hospital in Garran and the 174-bed Calvary Public Hospital in Bruce. Both are teaching institutions.[73][74][75][76] The largest private hospital is the Calvary John James Hospital in Deakin.[77][78] Calvary Private Hospital in Bruce and Healthscope's National Capital Private Hospital in Garran are also major healthcare providers.[73][75]

Canberra has 10 aged care facilities. Canberra's hospitals receive emergency cases from throughout southern New South Wales,[79] and ACT Ambulance Service is one of four operational agencies of the ACT Emergency Services Authority.[80] NETS provides a dedicated ambulance service for inter-hospital transport of sick newborns within the ACT and into surrounding New South Wales.[81]

Transport

The automobile is by far the dominant form of transport in Canberra and the Territory.[82] The city is laid out so that arterial roads connecting inhabited clusters run through undeveloped areas of open land or forest, which results in a low population density;[83] this also means that idle land is available for the development of future transport corridors if necessary without the need to build tunnels or acquire developed residential land. In contrast, other capital cities in Australia have substantially less green space.[84]

Canberra's districts are generally connected by parkways—limited access dual carriageway roads[82][85] with speed limits generally set at a maximum of 100 km/h (62 mph).[86][87] An example is the Tuggeranong Parkway which links Canberra's CBD and Tuggeranong, and bypasses Weston Creek.[88] In most districts, discrete residential suburbs are bounded by main arterial roads with only a few residential linking in, to deter non-local traffic from cutting through areas of housing.[89]

ACTION, the government-operated bus service, provides public transport throughout Canberra.[90] Qcity Transit provides bus services between Canberra and nearby areas of New South Wales through their Transborder Express brand (Murrumbateman and Yass)[91] and as Qcity Transit (Queanbeyan).[92] A light rail line is under construction. It will be completed in April 2019 and will link the CBD with the northern district of Gungahlin. At the 2016 census, 7.1% of the journeys to work involved public transport while 4.5% walked to work.[93]

There are two local taxi companies. Aerial Capital Group enjoyed monopoly status until the arrival of Cabxpress in 2007.[94] In October 2015, the ACT Government passed legislation to regulate ride sharing, allowing ride share services including Uber to operate legally in Canberra.[95][96][97] The ACT Government was the first jurisdiction in Australia to enact legislation to regulate the service.[98]

An interstate NSW TrainLink railway service connects Canberra to Sydney.[99] Canberra's railway station is in the inner south suburb of Kingston.[100] Train services to Melbourne are provided by way of a NSW TrainLink bus service which connects with a rail service between Sydney and Melbourne in Yass, about a one-hour drive from Canberra.[99][101]

Canberra is about three hours by road from Sydney on the Federal Highway (National Highway 23),[102] which connects with the Hume Highway (National Highway 31) near Goulburn, and seven hours by road from Melbourne on the Barton Highway (National Highway 25), which joins the Hume Highway at Yass.[102] It is a two-hour drive on the Monaro Highway (National Highway 23) to the ski fields of the Snowy Mountains and the Kosciuszko National Park.[101] Batemans Bay, a popular holiday spot on the New South Wales coast, is also two hours away via the Kings Highway.[101]

Canberra Airport provides direct domestic services to Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Gold Coast and Perth, with connections to other domestic centres.[103] There are also direct flights to small regional towns: Dubbo and Newcastle in New South Wales. Regular commercial international flights operate to Singapore and Wellington from the airport four times a week.[104] Canberra Airport is, as of September 2013, designated by the Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development as a restricted use designated international airport.[105] Until 2003, the civilian airport shared runways with RAAF Base Fairbairn. In June of that year, the Air Force base was decommissioned and from that time the airport was fully under civilian control.[106]

Utilities

The government-owned ACTEW Corporation manages the Territory's water and sewerage infrastructure.[108] ActewAGL is a joint venture between ACTEW and AGL, and is the retail provider of Canberra's utility services including water, natural gas, electricity, and also some telecommunications services via a subsidiary TransACT.[109]

Canberra's water is stored in four reservoirs, the Corin, Bendora and Cotter dams on the Cotter River and the Googong Dam on the Queanbeyan River. Although the Googong Dam is located in New South Wales, it is managed by the ACT government.[110] ACTEW Corporation owns Canberra's two wastewater treatment plants, located at Fyshwick and on the lower reaches of the Molonglo River.[111][112]

Electricity for Canberra mainly comes from the national power grid through substations at Holt and Fyshwick (via Queanbeyan).[113] Power was first supplied from a thermal plant built in 1913, near the Molonglo River, but this was finally closed in 1957.[114][115] The ACT has four solar farms, which were opened between 2014 and 2017: Royalla (rated output of 20 megawatts, 2014),[116] Mount Majura (2.3 MW, 2016),[107] Mugga Lane (13 MW, 2017)[117] and Williamsdale (11 MW, 2017).[118] In addition numerous houses in Canberra have photovoltaic panels and/or solar hot water systems. In 2015/16, rooftop solar systems supported by the ACT government's feed-in tariff had a capacity of 26.3 megawatts, producing 34,910 MWh. In the same year, retailer-supported schemes had a capacity of 25.2 megawatts and exported 28,815 MWh to the grid (power consumed locally was not recorded).[119]

The ACT has the highest rate with internet access at home (94 per cent of households in 2014–15).[120]

Economy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2019) |

The economic activity of the Australian Capital Territory is heavily concentrated around the city of Canberra.

A stable housing market, steady employment and rapid population growth in the 21st century have led to economic prosperity and, in 2011, CommSec ranked the ACT as the second best performing economic region in the country.[121] This trend continued into 2016, when the territory was ranked the third best performing out of all of Australia's states and territories.[122]

In 2017-18, the ACT had the fastest rate of growth in the nation due to a rapid growth in population, a strongly performing higher education sector as well as a significant housing and infrastructure investment.[123]

Higher education is the Territory's largest export industry.[123][124] Canberra is home to a significant number of universities and higher education providers. The other major services exports of the ACT in 2017-18 were government services and personal travel.[124] The major goods exports of the Territory in 2017-18 were gold coin, legal tender coin, metal structures and fish, though these represent a small proportion of the economy compared to services exports.[124]

The economy of the ACT is largely dependent on the public sector with 30% of the jobs in the Territory being in the public sector.[125] Decisions by the federal government regarding the public service can have a significant impact on the Territory's economy.[125]

The ACT's gross state product in 2017-18 was $39,792,000,000 and the Territory's economy represents 2.2% of the overall gross domestic product of Australia.[124]

See also

- Community Based Corrections

- Human Rights Act 2004

- Index of Australia-related articles

- Revenue stamps of the Australian Capital Territory

References

- ^ a b "Jervis Bay Territory Governance and Administration". Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Australian Capital Territory". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Attribution International license.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Attribution International license.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fitzgerald, Alan (1987). Canberra in two centuries: A pictorial history. Clareville Press. pp. 4–5, 12, 92–93, 115, 128. ISBN 0-909278-02-4.

- ^ a b Gillespie, Lyall (1984). Aborigines of the Canberra Region. Canberra: Wizard (Lyall Gillespie). pp. 1–25. ISBN 0-9590255-0-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Gillespie, Lyall (1991). Canberra 1820–1913. Australian Government Publishing Service. pp. 3–9, 110–111, 149, 278, 303. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- ^ a b c d Fitzhardinge, L. F. (1975). Old Canberra and the search for a capital. Canberra & District Historical Society. pp. 1–3, 31–32. ISBN 0-909655-02-2.

- ^ Watson, F. (1931). "Special Article: Canberra Past and Present". Year Book Australia. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "Kiandra". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 February 2005. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ a b Wigmore, Lionel (1971). Canberra: history of Australia's national capital. Dalton Publishing Company. pp. 20, 113. ISBN 0-909906-06-8.

- ^ Birtles, Terry G. (2004). "Contested places for Australia's capital city" (PDF). 11th Annual Planning History Conference. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "A4 Report Map of Australia". Geoscience Australia. 16 November 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Seat of Government Act 1908 (Cth)". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "History of the NCA". National Capital Authority. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Sparke, Eric (1988). Canberra 1954–1980. Australian Government Publishing Service. pp. 30, 170–180. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- ^ Gibbney, Jim (1988). Canberra 1913–1953. Australian Government Publishing Service. pp. 231–237. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- ^ Andrews, W.C. (1990). Canberra's Engineering Heritage. Institution of Engineers Australia. p. 90. ISBN 0-85825-496-4.

- ^ Overall, John (1995). Canberra: yesterday, today & tomorrow: a personal memoir. Federal Capital Press of Australia. pp. 128–129. ISBN 0-9593910-6-1.

- ^ "Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 (Cth)". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 July 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Past ACT Legislative Assembly Elections". ACT Electoral Commission. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Turbulent 20yrs of self-government". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 11 May 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ How were the ACT's boundaries determined?

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Climate of Canberra Area". Bureau of Meteorology. 12 July 2009. Archived from the original on 19 November 2003. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 12 July 2009 suggested (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Climate: Australian Capital Territory". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations: Canberra Airport Comparison". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^

- "Special climate statement 36 – Unseasonal cold in southeast Australia" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "ACT in September 2012". Bureau of Meteorology. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "ACT in December 2012". Bureau of Meteorology. 2 January 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Special Climate Statement 43 – extreme heat in January 2013" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "ACT in October 2013". Bureau of Meteorology. 1 November 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ McLeod, Ron (2003). Inquiry into the Operational Response to the January 2003 Bushfires in the ACT (PDF). Canberra, ACT. ISBN 0-642-60216-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Entry to the ACT Heritage Register – 20010. Woolshed Creek Fossil Site (PDF), ACT Heritage Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2005

- ^ "State Circle Cutting (Place ID 105733)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government.

- ^ National Trust of Australia – Deakin Anticline, archived from the original on 6 July 2004

- ^ Antony Green (22 September 2016). "Summary of Candidates and Parties Contesting 2016 ACT Election". ABC Elections.

- ^ Three Levels of Law-Making, Parliamentary Education Office, archived from the original on 16 May 2013

- ^ Factsheet – Hare-Clark electoral system, ACT Electoral Commission, 5 July 2012, archived from the original on 6 June 2013

- ^ "Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 – Sect 39".

- ^ COAG Members, Council of Australian Governments, archived from the original on 19 July 2013

- ^ "Territory Government", 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2012, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 24 May 2012, retrieved 21 October 2013

- ^ "Disallowance powers removed from ACT self-government legislation". News, Events and Conferences. ACT Legislative Assembly. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Territories Self-Government Legislation Amendment (Disallowance and Amendment of Laws) Act 2011 (Cth)". ComLaw. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Crime". Australian Federal Police. ACT Policing. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Benjamin Spagnolo (22 October 2015). The Continuity of Legal Systems in Theory and Practice. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-84946-884-8.

While the Jervis Bay Territory was constituted as a separate Territory on acceptance by the Commonwealth, it was 'annexed' to the Federal Capital Territory, to the extent that the laws there in force from time to time were 'applied' in the still legally distinct Jervis Bay Territory.

- ^ "Jervis Bay Court". www.courts.act.gov.au. 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915". Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

ABSPopwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "ACT Population Projections: 2018 to 2058" (PDF). ACT Government. January 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Wigmore 1971, p. 64.

- ^ a b Sparke 1988, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Dept of Education & Training. 2011 Archived 10 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2005. Schools in the ACT [dead link]

- ^ ACT Department of Education and Training. 2005. Enrolments in ACT Schools 1995 to 2005 Archived 17 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2005. Education in the ACT [dead link]

- ^ a b c d "Lake Burley Griffin Interactive Map". National Capital Authority. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Locations and opening hours". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "The Shine Dome". Australian Academy of Science. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Visiting the High Court". High Court of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Visitors". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Opening hours". Royal Australian Mint. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "Outdoor and Nature". Visit Canberra. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 201

- ^ "Canberra Museum and Gallery". ACT Government. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Lanyon". ACT Museums and Galleries. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Minders of Tuggeranong Homestead". Chief Minister's Department. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Mugga-Mugga". ACT Museums and Galleries. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blundells Cottage". National Capital Authority. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Calthorpes' House". ACT Museums and Galleries. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Atkinson, Ann; Knight, Linsay; McPhee, Margaret (1996). The Dictionary of Performing Arts in Australia: Opera, Dance, Music. Allen & Unwin. pp. 46–47. ISBN 1-86448-005-X.

- ^ Daly, Margo (2003). Rough Guide to Australia. Rough Guides. p. 67. ISBN 1-84353-090-2.

- ^ "Fact sheets". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Vaisutis 2009, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Universal Publishers 2007, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Vaisutis 2009, pp. 278.

- ^ Wigmore 1971, p. 87.

- ^ Waterford, Jack (3 March 2013). "History of a paper anniversary". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013.

- ^ "Subscription television". TransACT. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Hospitals". ACT Health. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Canberra Hospital". ACT Health. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Contact Us & Location Map". Calvary Health Care ACT. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Public Hospital". Calvary Health Care ACT. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Cronin, Fiona (12 August 2008). "Chemo crisis to hit ACT patients". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to Calvary John James Hospital". Calvary John James Hospital. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "About Emergency". ACT Government Health Information. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Us". ACT Emergency Services Authority. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "What is NETS?". Newborn Emergency Transport Service. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Canberra's transport system" (PDF). Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Penguin Books Australia 2000, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Penguin Books Australia 2000, pp. 3–6, 32–35, 53–59, 74–77, 90–91, 101–104.

- ^ "ACT Road Hierarchy". ACT Government. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ "Survey shows speeding at disputed camera site". Chief Minister's Department. 17 July 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Speeding". Australian Federal Police. 20 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 November 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Universal Publishers 2007, pp. 57, 67, 77.

- ^ Universal Publishers 2007, pp. 1–100.

- ^ "Corporate". ACTION. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "About Us". Transborder Express. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "About Us". Qcity Transit. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Canberra – Queanbeyan (Canberra Part)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Taxi company 'not concerned' at losing monopoly". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Uber launches in ACT as Canberra becomes first city to regulate ride sharing". Australian Broadcasting Commission. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015.

- ^ McIlroy, Tom (30 October 2015). "Uber goes live in Canberra with more than 100 drivers registered". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015.

- ^ "ACT chief minister launches regulated Uber in Canberra, calling it 'a real step forward'". The Guardian. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015.

- ^ "Fully-regulated Uber services start in Canberra". Australian Financial Review. Fairfax Media. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Southern timetable". NSW TrainLink. 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Travel pass agencies". CountryLink. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Penguin Books Australia 2000, pp. 20.

- ^ a b Penguin Books Australia 2000, inside cover.

- ^ "Departures". Canberra Airport. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Singapore Airlines flight arrives in Canberra, first direct international flight in more than a decade". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Designated International Airports in Australia". Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. 27 February 2013. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- ^ Hogan, Richard (July 2003). "Farewell to Fairbairn". Air Force. 45 (12). Royal Australian Air Force.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b "Mount Majura Solar Farm powers up in ACT". Solar Choice. 11 October 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "What we do". ACTEW. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About our business". ActewAGL. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "The Water Network". ActewAGL. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fyshwick Sewage Treatment Plant". ActewAGL. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lower Molonglo Water Quality Control Centre". ActewAGL. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Independent Competition and Regulatory Commission (October 2003). "Review of Contestable Electricity Infrastructure Workshop" (PDF). p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ "The Founding of Canberra". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 March 1913. p. 5. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "20048. Kingston Powerhouse Historic Precinct (Entry to the ACT Heritage Register)" (PDF). ACT Heritage Council. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Australia's largest solar farm opens in the ACT" (Press release). ACT Government. 3 September 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Mugga Lane solar farm opens, bringing ACT to 35 per cent renewable energy". The Canberra Times. 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Government unveils 36,000 new solar panels at Williamsdale". The Canberra Times. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2015–16 Annual Feed-in Tariff Report" (PDF). ACT Government. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "8146.0 – Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2014–15". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Australian Capital Territory is Australia's best economy". International Business Times. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "CommSec State of the States places NSW economy first". 27 January 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ a b Jervis-Bardy, Dan (29 January 2019). "'Glitter starting to fade': ACT economic growth to slow". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Fact sheets for countries, economies and regions: Australian Capital Territory" (PDF). Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Kennedy, Maddison (July 2017). "The ACT economy still going strong". Dixon Advisory. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)

External links

- Statistical Subdivisions of the Australian Capital Territory

Geographic data related to Australian Capital Territory at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Australian Capital Territory at OpenStreetMap