Basilosaurus

| Basilosaurus Temporal range: Late Eocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

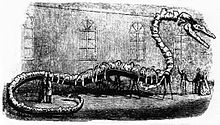

| B. cetoides, National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | †Basilosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Basilosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Basilosaurus Harlan 1834 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Basilosaurus ("king lizard") is a genus of prehistoric cetacean that existed during the Late Eocene, 40 to 35 million years ago (mya). The first fossil of B. cetoides was discovered in the United States and was initially believed to be some sort of reptile, hence the suffix -saurus, but it was later found to be a marine mammal. Fossils of B. isis have been found in Egypt and Jordan. Basilosaurus fossils have also been found in Poland and the Ukraine.[disputed – discuss]

Basilosaurus is a state fossil of Alabama and Mississippi.

Biology

Measuring 15–18 m (49–59 ft),[1][2] Basilosaurus cetoides is one of the largest-known animals to exist from K-Pg extinction event 66 million years ago (mya) to around 15 million years ago when modern cetaceans began to reach enormous sizes.[3] B. isis is slightly smaller than B. cetoides.[4]

Cranium

The dental formula for B. isis is 3.1.4.23.1.4.3. The upper and lower molars and second to fourth premolars are double-rooted and high-crowned.[5]

The head of Basilosaurus did not have room for a melon like modern toothed whales, and the brain was smaller in comparison, as well. They are not believed to have had the social capabilities of modern whales.

Fahlke et al. 2011 concluded that the skull of Basilosaurus is asymmetrical like in modern toothed whales, and not, as previously assumed, symmetrical like in baleen whales and artiodactyls closely related to cetaceans. In modern toothed whales, this asymmetry is associated with high-frequency sound production and echolocation, neither of which is thought to be present in Basilosaurus. This cranial torsion probably evolved in protocetids and basilosaurids together with directional underwater hearing and the sound-receiving apparatus in the mandible (the auditory fat pad and the pan bone (thin portion of mandible)).[6]

In the basilosaur skull, the inner and middle ear are enclosed by a dense tympanic bulla.[7] The synapomorphic cetacean air sinus system is partially present in basilosaurids, including the pterygoid, peribullary, maxillary, and frontal sinuses.[8] The periotic bone, which surrounds the inner ear, is partially isolated. The mandibular canal is large and laterally flanked by a thin bony wall, the pan bone or acoustic fenestra. These features enabled basilosaurs to hear directionally in water.[7]

The ear of basilosaurids is more derived than those in earlier archaeocetes, such as remingtonocetids and protocetids, in the acoustic isolation provided by the air-filled sinuses inserted between the ear and the skull. The basilosaurid ear did, however, have a large external auditory meatus, strongly reduced in modern cetaceans, but though this was probably functional, it can have been of little use under water.[9]

Hind limbs

A 16-meter (52 ft) individual of B. isis had 35-centimeter-long (14 in) hind limbs with fused tarsals and only three digits. The limited size of the limb and the absence of an articulation with the sacral vertebrae, makes a locomotory function unlikely.[10] Analysis has shown that the reduced limbs could rapidly adduct between only two positions.[citation needed]

Spine and movement

A complete Basilosaurus skeleton was found in 2015, and several attempts have been made to reconstruct the vertebral column from partial skeletons. Kellogg 1936 estimated a total of 58 vertebrae, based on two partial and nonoverlapping skeletons of B. cetoides from Alabama. More complete fossils uncovered in Egypt in the 1990s allowed a more accurate estimation: the vertebral column of B. isis has been reconstructed from three overlapping skeletons to a total of 70 vertebrae with a vertebral formula interpreted as seven cervical, 18 thoracic, 20 lumbar and sacral, and 25 caudal vertebrae. The vertebral formula of B. cetoides can be assumed to be the same.[11]

Basilosaurus has an anguilliform (eel-like) body shape because of the elongation of the centra of the thoracic through anterior caudal vertebrae. In life, these vertebrae were filled with marrow, and because of the enlarged size, made them buoyant. Basilosaurus probably swam predominantly in two dimensions at the sea surface, in contrast to the smaller Dorudon, which was likely a diving, three-dimensional swimmer.[12] The skeletal anatomy of the tail suggests that a small fluke was probably present, which would have aided only vertical motion. Most reconstructions show a small, speculative dorsal fin similar to a rorqual's, but other reconstructions show a dorsal ridge.[citation needed]

Similarly sized thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and caudal vertebrae imply that it moved in an anguilliform fashion, but predominantly in the vertical plane. Paleontologist Philip D. Gingerich theorized that Basilosaurus may also have moved in a very odd, horizontal anguilliform fashion to some degree, something completely unknown in modern cetaceans. The vertebrae appear to have been hollow, and likely also fluid-filled. This would imply that Basilosaurus typically functioned in only two dimensions at the ocean surface, compared with the three-dimensional habits of most other cetaceans. Judging from the relatively weak axial musculature and the thick bones in the limbs, Basilosaurus is not believed to have been capable of sustained swimming or deep diving, or terrestrial locomotion.[citation needed]

Feeding

The cheek teeth of Basilosaurus retain a complex morphology and functional occlusion. Heavy wear on the teeth reveals that food was first chewed then swallowed.[7] Scientists were able to estimate the bite force of Basilosaurus by analyzing the scarred skull bones of another species of prehistoric whale, Dorudon, and concluded they could bite with a force of 3,600 pounds per square inch (25,000 kPa).[13]

Analyses of the stomach contents of B. cetoides has shown that this species fed exclusively on fish and sharks, while bite marks on the skulls of juvenile Dorudon have been matched with the dentition of B. isis, suggesting a dietary difference between the two species, similar to that found in different populations of modern killer whales.[14] It was probably an active predator rather than a scavenger.[15] The discovery of juvenile Dorudon at Wadi Al Hitan bearing distinctive bite marks on their skulls indicates that B. isis would have aimed for the skulls of its victims to kill its prey, then subsequently tore its meals apart, based on the disarticulated remains of the Dorudon skeletons. The finding further cements theories that B. isis was an apex predator that may have hunted newborn and juvenile Dorudon at Wadi Al Hitan when mothers of the latter came to give birth.[16]

Extinction

Basilosaurus fossil record seems to end at about 33-35 mya.[17]Basilosaurus extinction coincides with the Eocene extinction event which happened 33.9 mya.[18] this is extinction saw the the death of all of basilosaurus group, the Archaeoceti. The Extinction has been attributed to a few factors including, volcanic activity,Meteor impacts and a sudden change in climate. A change in the climate might have caused changes in the ocean by disrupting oceanic circulation.[19][20][21]

Taxonomic history

Etymology

The two species of Basilosaurus are B. cetoides, whose remains were discovered in the United States, and B. isis, which was discovered in Egypt. B. cetoides is the type species for the genus.[22][23] During the early 19th century, B. cetoides fossils were so common (and sufficiently large) that they were regularly used as furniture in the American South.[24] Vertebrae were sent to the American Philosophical Society by a Judge Bry of Arkansas and Judge John Creagh of Clarke County, Alabama. Both fossils ended up in the hands of the anatomist Richard Harlan, who requested more examples from Creagh.[25][26] The first bones were unearthed when rain caused a hillside full of sea shells to slide. The bones were lying in a curved line "measuring upwards of four hundred feet in length, with intervals which were vacant." Many of these bones were used as andirons and destroyed; Bry saved the bones he could find, but was convinced more bones were still to be found on the location. Bry speculated that the bones must have belonged to a "sea monster" and supplied "a piece having the appearance of a tooth" to help determine which kind.[27]

Harlan identified the tooth as a wedge-shaped shell and instead focused on "a vertebra of enormous dimensions" which he assumed belonged to the order "Enalio-Sauri of Conybeare", "found only in the sub-cretaceous series."[28] He noted that some parts of the vertebra were similar to those of Plesiosaurus, but that they were completely different in proportions. Comparing his vertebra to those of large dinosaurs such as Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, Harlan concluded that his specimen was considerably larger—he estimated the animal to have been no less than 80–100 ft (24–30 m) long—and therefore suggested the name Basilosaurus, meaning “king lizard”.[29]

Harlan brought his assembled specimens (including fragments of jaw and teeth, humerus, and rib fragments) to the UK where he presented them to anatomist Richard Owen. Owen concluded that the molar teeth were two-rooted, a dental morphology unknown in fishes and reptiles, and more complex and varied than in any known reptile, and therefore that the specimen must be a mammal. Owen correctly associated the teeth with cetaceans, but he thought it was an herbivorous animal, similar to sirenians.[30] Consequently, Owen proposed renaming the find Zeuglodon cetoides (“whale-like yoke teeth” in reference to the double-rooted teeth) and Harlan agreed.[31]

Wadi El Hitan

Wadi El Hitan, otherwise known as Whale Valley, is an Egyptian sandstone formation where many early-whale skeletons were discovered.[32] German botanist Georg August Schweinfurth discovered the first archaeocete whale in Egypt (Zeuglodon osiris, now Saghacetus osiris) in 1879. He visited the Qasr el Sagha Formation in 1884 and 1886 and missed the now famous Wadi El Hitan by a few kilometers. German paleontologist Wilhelm Barnim Dames described the material, including the type specimen of Z. osiris, a well-preserved dentary.[33]

Hugh Beadnell, head of the Geological Survey of Egypt 1896–1906,[34] named and described Zeuglodon isis in Andrews 1904 based on a partial mandible and several vertebrae from Wadi El Hitan in Egypt.[35] Andrews 1906[36] described a skull and some vertebrae of a smaller archaeocete and named it Prozeuglodon atrox, now known today as Dorudon atrox. Kellogg 1936 discovered deciduous teeth in this skull and it was then believed to be a juvenile [Pro]zeuglodon isis for decades before more complete fossils of mature Dorudon were discovered.[37][38][39]

In the 1980s, Elwyn L. Simons and Philip D. Gingerich started to excavate at Qasr el-Sagha and Wadi El Hitan with the hope of finding material that could match archaeocete fossils from Pakistan. Since then, over 500 archaeocete skeletons have been found at these two locations, of which most are B. isis or D. atrox, several of the latter carrying bite marks assumed to be from the former.[40] Gingerich, Smith & Simons 1990 described additional fossils including foot bones and speculated that the reduced hind limbs were used as copulatory guides.[41]

In 2016, a complete skeleton, the first-ever found for Basilosaurus, was uncovered in Wadi El Hitan, preserved with the remains of another whale (which was either a last meal or an unborn fetus) inside its ribcage. This specimen was later found to have eaten Dorudon and several species of fish.[42] The whale's skeleton also shows signs of scavenging or predation by large sharks, among them the otodontid Carcharocles sokolovi, an ancestor to the later C. megalodon.[43][44]

Nomina dubia

- Zeuglodon wanklyni was described in 1876 based on a skull found in the Wanklyn's Barton Cliff in the United Kingdom. This single specimen, however, quickly disappeared and has since been declared a nomen nudum or referred to as Zygorhiza wanklyni.[45]

- Zeuglodon vredense or vredensis was named in the 19th century based on a single, isolated tooth without any kind of accompanying description, and Kellogg 1936 therefore declared it a nomen nudum.[46][47]

- Zeuglodon puschi[i] from Poland was named by Brandt 1873. Kellogg 1936 noted that the species is based on an incomplete vertebra of indeterminable position and, therefore, that the species is invalid.[48][49]

- Zeuglodon brachyspondylus was described by Müller 1849 based on some vertebrae from Zeuglodon hydrarchus, better known as Dr Albert Koch's "Hydrarchos". Kellogg 1936, synonymized it with Pontogeneus priscus, which Uhen 2005 declared a nomen dubium.

Reassigned species

- Basilosaurus drazindai was named by Gingerich et al. 1997 based on a single lumbar vertebra. It was later declared a nomen dubium by Uhen (2013), but Gingerich and Zouhri (in press) re-assigned it to Eocetus.[50][51]

- Zeuglodon elliotsmithii, Z. sensitivius, Z. sensitivus, and Z. zitteli were synonymized and grouped under the genus Saghacetus by Gingerich 1992.

- Zeuglodon paulsoni from Ukraine was named by Brandt 1873. It was synonymized with Platyosphys but is now considered nomen dubium. Gingerich and Zouhri (in press), however, maintain Platyosphys as valid.[52][51]

In popular culture

In the BBC documentary, Walking with Beasts, a female Basilosaurus isis after mating struggles to stay alive in the changing world, trying to find food for her and her unborn calf. The Basilosaurus in the show is eating Durodon. Basilosaurus was mentioned once in the novel Moby Dick in chapter 104.[53][54] The species B. cetoides is the state fossil of Alabama,[4] and Mississippi named the prehistoric whale (B. cetoides and Zygorhiza kochii) state fossil.[55][56]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Houssaye, A; Tafforeau, P; de Muizon, C; Gingerich, PD (2011). "Evolution of Whales from Land to Sea". PLoS ONE. 10 (2): e0118409. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118409. PMC 4340927. PMID 25714394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gingerich, P. D. (2008). "Early Evolution of Whales: A Century of Research in Egypt" (PDF). In Fleagle, J. G.; Gilbert, C. C. (eds.). Elwyn Simons: A Search for Origins. Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects. pp. 107–124. ISBN 978-0-387-73895-6.

- ^ "Explore Our Collections: Basilosaurus". Smithonian, National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b Gingerich, Philip D. "Basilosaurus cetoides". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Fahlke 2012, p. 6

- ^ Fahlke et al. 2011

- ^ a b c Gingerich & Uhen 1998, p. 4

- ^ Racicot & Berta 2013, p. 50

- ^ Nummela et al. 2004, p. 776

- ^ Bejder & Hall 2002, p. 448

- ^ Zalmout, Mustafa & Gingerich 2000, Discussion, p. 202

- ^ Gingerich 1998, pp. 433, 435

- ^ Snively, E.; Fahlke, J. M.; Welsh, R. C. (2015). "Bone-Breaking Bite Force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Late Eocene of Egypt Estimated by Finite Element Analysis". PLoS ONE. 10 (2): e0118380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118380. PMC 4340796. PMID 25714832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fahlke 2012, p. 14

- ^ Snively, Eric; Fahlke, Julia M.; Welsh, Robert C. (25 February 2015). "Bone-Breaking Bite Force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Late Eocene of Egypt Estimated by Finite Element Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0118380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118380. PMC 4340796. PMID 25714832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0209021#ack

- ^ "†Basilosaurus Harlan 1834 (whale)". PBDB.

- ^ Ivany, Linda C.; Patterson, William P.; Lohmann, Kyger C. (2000). "Cooler winters as a possible cause of mass extinctions at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary". Nature. 407 (6806): 887–890. doi:10.1038/35038044. PMID 11057663.

- ^ "Basilosaurus cetoides". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Philip D. Gingerich.

- ^ "Russia's Popigai Meteor Crash Linked to Mass Extinction". Yahoo news. Becky Oskin, Senior Writer.

- ^ Molina, Eustoquio; Gonzalvo, Concepción; Ortiz, Silvia; Cruz, Luis E. (2006-02-28). "Foraminiferal turnover across the Eocene–Oligocene transition at Fuente Caldera, southern Spain: No cause–effect relationship between meteorite impacts and extinctions". Marine Micropaleontology. 58 (4): 270–286. Bibcode:2006MarMP..58..270M. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2005.11.006.

- ^ Zalmout, Mustafa & Gingerich 2000

- ^ "Basilosaurus". BBC Nature. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Zimmer 1998, p. 141

- ^ Switek, Brian (September 21, 2008). "The Legacy of the Basilosaurus". ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Brian Switek (December 2010). "How Did Whales Evolve?". Smithsonian.

- ^ Harlan 1834, p. 400

- ^ Harlan 1834, p. 401

- ^ Harlan 1834, pp. 402–403

- ^ Owen 1839, pp. 72–73

- ^ Owen 1839, p. 75

- ^ "Wadi Al-Hitan". World Heritage Site. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Gingerich 2007, pp. 110–112

- ^ Gingerich 2007, p. 113

- ^ Andrews 1904, pp. 214–215

- ^ Andrews 1906, pp. 255

- ^ Kellogg 1936, p. 81

- ^ Gingerich 2007, p. 114

- ^ Uhen 2004, p. 11

- ^ Gingerich 2007, pp. 117–119

- ^ Gingerich, Smith & Simons 1990, Abstract

- ^ https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0209021#ack

- ^ Griffiths, Sarah (2015-06-04). "Egyptian fossils reveal a whale inside a whale, eaten by a shark | Daily Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ^ https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0209021#ack

- ^ Basilosauridae in the Paleobiology Database: Taxonomic history. Retrieved August 2013.

- ^ Kellogg 1936, p. 264

- ^ Zeuglodon vredense (nomen nudum) in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved August 2013.

- ^ Kellogg 1936, p. 263

- ^ Zeuglodon puschii (nomen dubium) in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved August 2013.

- ^ Basilosaurus drazindai in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved August 2013.

- ^ a b Gingerich, Philip D.; Zouhri, Samir (2015). "New fauna of archaeocete whales (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Bartonian middle Eocene of southern Morocco". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 111: 273–286. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2015.08.006.

- ^ Gol'din & Zvonok 2013, Abstract

- ^ "CHAPTER 104: The Fossil Whale". Literature page.com.

- ^ "Walking with Beasts". BBC. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "State Symbols". State of Mississippi. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fossil whale: State Fossil of Mississippi (PDF), Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, 1991, retrieved 2019-05-09

Sources

- Andrews, C. W. (1904). "Further notes on the mammals of the Eocene of Egypt. Part III". Geological Magazine. 5. 1 (5): 211–215. doi:10.1017/s0016756800119624.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Andrews, C. W. (1906). A descriptive catalogue of the Tertiary Vertebrata of the Fayûm, Egypt. British Museum (Natural History). OCLC 3675777.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bejder, Lars; Hall, Brian K. (2002). "Limbs in whales and limblessness in other vertebrates: mechanisms of evolutionary and developmental transformation and loss" (PDF). Evolution and Development. 4 (6): 445–458. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2002.02033.x. PMID 12492145.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brandt, J. F., von (1873). "Über bisher in Russland gefundene Reste von Zeuglodonten". Mélanges Biologiques Tirés du Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de St. Pétersbourg. 9: 111–112.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fahlke, Julia M. (2012). "Bite marks revisited – evidence for middle-to-late Eocene Basilosaurus isis predation on Dorudon atrox (both Cetacea, Basilosauridae)" (PDF). Palaeontologia Electronica. 15 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fahlke, Julia M.; Gingerich, Philip D.; Welsh, Robert C.; Wood, Aaron R. (2011). "Cranial asymmetry in Eocene archaeocete whales and the evolution of directional hearing in water". PNAS. 108 (35): 14545–14548. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108927108. PMC 3167538. PMID 21873217.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gidley, J. W. (1913). "A recently mounted Zeuglodon skeleton in the United States National Museum". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 44 (1975): 649–654. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.44-1975.649.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, P. D. (1992). "Marine Mammals (Cetacean and Sirenia) from the Eocene of Gebel Mokattam and Fayum, Egypt: Stratigraphy, Age, and Paleoenvironments". University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology. 30: 1–84. hdl:2027.42/48630. OCLC 26941847.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, P. D. (1998). "Paleobiological Perspectives on Mesonychia, Archaeoceti, and the Origin of Whales" (PDF). In Thewissen, J. G. M. (ed.). The Emergence of Whales: Evolutionary Patterns in the Origin of Cetacea. Advances in Vertebrate Paleobiology. Vol. 1. Springer. pp. 424–439. ISBN 9780306458538.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, P. D. (2007). "Early evolution of whales: a century of research in Egypt" (PDF). In Fleagle, J. G.; Gilbert, Christopher C. (eds.). Elwyn Simons: A Search for Origins. New York: Springer. pp. 107–124. ISBN 978-0-387-73896-3. OCLC 233971398.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, P. D.; Arif, M; Bhatti, M Akram; Anwar, M; Sanders, William J (1997). "Basilosaurus drazindai and Basiloterus hussaini, New Archaeoceti (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Eocene Drazinda Formation, with a Revised Interpretation of Ages of Whale-Bearing Strata in the Kirthar Group of the Sulaiman Range, Punjab (Pakistan)". Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 30 (2): 55–81. hdl:2027.42/48652. OCLC 742731913.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, Philip D.; Smith, B. Holly; Simons, Elwyn L. (1990). "Hind Limbs of Eocene Basilosaurus: Evidence of Feet in Whales". Science. 249 (4965): 154–157. doi:10.1126/science.249.4965.154. PMID 17836967.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gingerich, P. D.; Uhen, Mark D. (1998). "Likelihood estimation of the time of origin of Cetacea and the time of divergence of Cetacea and Artiodactyla" (PDF). Palaeontologia Electronica. 1 (2): 1–45.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gol'din, Pavel; Zvonok, Evgenij (2013). "Basilotritus uheni, a New Cetacean (Cetacea, Basilosauridae) from the Late Middle Eocene of Eastern Europe". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (2): 254–268. doi:10.1666/12-080R.1.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harlan, R. (1834). "Notice of fossil bones found in the Tertiary formation of the State of Louisiana". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 4: 397–403. doi:10.2307/1004838. JSTOR 1004838. OCLC 63356837.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kellogg, R. (1923). "Description of two squalodonts recently discovered in the Calvert Cliffs, Maryland; and notes on the shark-toothed cetaceans". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 62 (2462): 1–69. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.62-2462.1. hdl:10088/15278. OCLC 82628874.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kellogg, R. (1936). A review of the Archaeoceti (PDF, 46 Mb). Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 681376.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lucas, Frederic A. (1900). "The pelvic girdle of Zeuglodon, Basilosaurus cetoides (Owen) with notes on other portions of the skeleton" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 23 (1211): 327–331. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.23-1211.327. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107351454. OCLC 75278090.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lydekker, R. (1892). "4. On Zeuglodont and other Cetacean Remains from the Tertiary of the Caucasus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 60 (4): 558–581. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1892.tb01782.x. OCLC 819196877.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Müller, Johannes Peter (1849). Über die fossilen Reste der Zeuglodonten von Nordamerika mit Rücksicht auf die europäischen Reste aus dieser Familie. Berlin: Reiner. pp. 1–38. OCLC 422134028.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, Sunil; Hussain, Taseer; Kumar, Kishor (2004). "Eocene evolution of whale hearing" (PDF). Nature. 430 (7001): 776–778. doi:10.1038/nature02720. PMID 15306808.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[permanent dead link][permanent dead link] - Owen, R. (1839). "Observations on the Basilosaurus of Dr. Harlan (Zeuglodon cetoides, Owen)". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 6: 69–79. doi:10.1144/transgslb.6.1.69.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Racicot, Rachel A.; Berta, Annalisa (2013). "Comparative Morphology of Porpoise (Cetacea: Phocoenidae) Pterygoid Sinuses: Phylogenetic and Functional Implications". Journal of Morphology. 274 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1002/jmor.20075. PMID 22965565.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanger, E. B. (1881). "On a molar tooth of Zeuglodon from the Tertiary beds on the Murray River near Wellington, S.A." Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 1 (5): 298–300. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988). Whales of the World. Brill Archive. ISBN 9780935848472.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Uhen, Mark D. (2002). "Basilosaurids". In Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Uhen, Mark D. (2004). "Form, Function, and Anatomy of Dorudon Atrox (Mammalia, Cetacea): An Archaeocete from the Middle to Late Eocene of Egypt". Papers on Paleontology. 34. hdl:2027.42/41255.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Uhen, M. D. (2005). "A new genus and species of archaeocete whale from Mississippi". Mississippi Geology. 43 (3): 157–172.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zalmout, I. S.; Mustafa, H. A.; Gingerich, P. D. (2000). "Priabonian Basilosaurus isis (Cetacea) from the Wadi Esh-Shallala Formation: first marine mammal from the Eocene of Jordan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 201–204. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0201:pbicft]2.0.co;2. OCLC 4908948040.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zimmer, Carl (1998). At the Water's Edge: Macroevolution and the Transformation of Life. Free Press. ISBN 9780684834900.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)