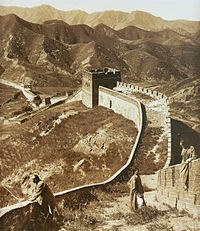

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (simplified Chinese: 万里长城; traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng; lit. 'The long wall of 10', '000 Li (里)¹') is a Chinese fortification built from the 5th century BC until the beginning of the 17th century, in order to protect the various dynasties from raids by Hunnic, Mongol, Turkic, and other nomadic tribes coming from areas in modern-day Mongolia and Manchuria. Several walls, also referred to as the Great Wall of China, were built since the 5th century BC, the most famous being the one built between 220 BC and 200 BC by the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang; this wall was located much further north than the current wall built during the Ming Dynasty, and little of it remains.

The Great Wall is the world's largest man-made structure, stretching over a formidable 6,352 km (3,948 miles), from Shanhai Pass on the Bohai Sea in the east, at the limit between "China proper" and Manchuria (Northeast China), to Lop Nur in the southeastern portion of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region [1]. Along most of its arc, it roughly delineates the border between North China and Inner Mongolia.

Notable areas

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|November 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

The “North Pass” of Juyongguan Pass is known as the Badaling. This particular area of the Great Wall is where most tourists visit. When used by the Chinese to protect their land, this wall was well manned by guards so as to guard China’s capital, Beijing. However, Badaling is very difficult to access. Made out of stone and bricks from the hills, this portion of the Great Wall is 7.8 meters high, and 5 meters wide.

Representing the Ming Great Wall, Jinshanling is considered to have the most striking sights of the Great Wall. It runs 11 kilometers long, ranges from 5 to 8 meters in height, and 6 meters across the bottom, narrowing up to 5 meters across the top. Wangjinglou is one of Jinshanling’s 67 watchtowers, rising 980 meters above sea level.

ShanHaiGuan Great Wall is referred to as the “Museum of the Construction of the Great Wall”, because of a temple, the Meng Jiang-Nu Temple, built during the Song Dynasty. The ShanHaiGuan Great Wall is known for many different things, both with the construction of the wall, and also its history.

The first pass of the Great Wall was located on the ShanhaiGuan (known as the “Number One Pass Under Heaven”), the first mountain the Great Wall climbs, Jia Shan, is also located here, as is the Jiumenkou, which is the only portion of the wall that was built as a bridge.

Characteristics of the Wall

Before the use of bricks, the Great Wall was mainly built from earth, stones and wood. Due to the difficulty in transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction, builders always tried to use local resources. Over the mountain ranges, the stones of the mountain were exploited and used; while in the plains, earth was rammed into solid blocks to be used in construction.

Before and during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), because the earth buildings could withstand the strength of small arms such as swords and spears and there was low technology of productivity, the Great Wall was primarily built by stamping earth between board frames. Consequently, only walls of just earth or earth with gravel inside were built. No fortresses were constructed along the wall, and no bricks were used in the gates at the wall's passes. Much of these sections have eroded away by now. During the time following the Han Dynasty (202-220 AD), earth and crude stones remained common building tools.

Bricks were heavily used in many areas of the wall during the Ming Dynasty, as well as materials such as tiles, lime, and stone. Bricks were easier to work with than earth and stone as their small size and light weight made them convenient to carry and augmented construction speed. Additionally, they could bear more weight and retain their integrity than rammed earth. Stone, though more difficult to use, can better hold well under its own weight than brick. Consequently, stones cut in rectangular shapes were used for the foundation, inner and outer brims, and gateways of the wall.

The steps that form the Great Wall of China are very steep and tall in some areas of the wall. Tourists often become exhausted climbing the wall, and traverse no more than a mile because of this reason. Along the wall on either side, are “holes” where the builders of the Great Wall didn’t place any bricks. They are a little over a foot tall, and about 9 inches in width. These holes were used to shoot arrows out of when being attacked.

Condition

While some portions near tourist centers have been preserved and even reconstructed, in many locations the Wall is in disrepair, serving as a playground for some villages and a source of stones to rebuild houses and roads. Sections of the Wall are also prone to graffiti and vandalism. Parts have been destroyed because the Wall is in the way of construction sites. Intact or repaired portions of the Wall near developed tourist areas are often plagued with hawkers of tourist kitsch. After one of the many runs for charity along the Great Wall, H.J.P Arnold questioned several runners about the status of the wall. A typical response was "The wall was clearly discernible and only moderately eroded along 22% of the run. The Wall was usually discernible but frequently broken/eroded 41% of the run, and scarcely discernible and almost totally eroded 37% of the run."

Watchtowers and barracks

The wall is complemented by defensive fighting stations, to which wall defenders may retreat if overwhelmed. With more than 10,000 watch towers (which were used to store weapons, house troops, and send smoke signals), each tower has unique and restricted stairways and entries to confuse attackers. Barracks and administrative centers are located at larger intervals.

Communication between the army units along the length of the Great Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance. Signal towers were built upon hill tops or other high points along the wall for their visibility.

Recognition

The Wall was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

Mao Zedong had a saying, Simplified Chinese: 不到长城非好汉, Traditional Chinese: 不到長城非好漢, pinyin: Bú dào Chángchéng fēi hǎo hàn, roughly meaning "You're not a real man if you haven't climbed the Great Wall".

From outer space

Richard Halliburton's 1938 book Second Book of Marvels said the Great Wall is the only man-made object visible from the moon, and a Ripley's Believe It or Not! cartoon from the same decade makes a similar claim. This belief has persisted, assuming urban legend status, sometimes even entering school textbooks. Arthur Waldron, author of the most authoritative history of the Great Wall, has speculated that the belief might go back to the fascination with the "canals" once believed to exist on Mars. (The logic was simple: If people on Earth can see the Martians' canals, the Martians might be able to see the Great Wall.)

In fact, the Great Wall is only a few meters wide - similar in size to highways and airport runways - and is about the same color as the soil surrounding it. It cannot be seen by the unaided eye from the distance of the moon, much less from Mars. If the Great Wall were visible from the moon, it would be easy to see from near-Earth orbit, but from near-Earth orbit it is barely visible, and only under nearly perfect conditions; it is no more conspicuous than many other manmade objects.

Astronaut William Pogue thought he had seen it from Skylab but discovered he was actually looking at the Grand Canal of China near Beijing. He spotted the Great Wall with binoculars, but said that "it wasn't visible to the unaided eye." US Senator Jake Garn claimed to be able to see the Great Wall with the naked eye from a space shuttle orbit in the early 1980s, but his claim has been disputed by several US astronauts. Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei said he could not see it at all.

Veteran US astronaut Gene Cernan has stated: "At Earth orbit of 160 km to 320 km high, the Great Wall of China is, indeed, visible to the naked eye." Ed Lu, Expedition 7 Science Officer aboard the International Space Station, adds that, "it's less visible than a lot of other objects. And you have to know where to look."

Neil Armstrong stated about the view from Apollo 11: "I do not believe that, at least with my eyes, there would be any man-made object that I could see. I have not yet found somebody who has told me they've seen the Wall of China from Earth orbit. ... I've asked various people, particularly Shuttle guys, that have been many orbits around China in the daytime, and the ones I've talked to didn't see it." [2]

Leroy Chiao, a Chinese-American astronaut, took a photograph from the International Space Station that shows the wall. It was so indistinct that the photographer was not certain he had actually captured it. Based on the photograph, the state-run China Daily newspaper concluded that the Great Wall can be seen from space with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to look [3].

These inconsistent results suggest the visibility of the Great Wall depends greatly on the seeing conditions, and also the direction of the light (oblique lighting widens the shadow). Features on the moon that are dramatically visible at times can be undetectable at other times due to changes in lighting direction; the same would be true of the Great Wall.

Based on the optics of resolving power (distance. versus the width of the iris: a few millimetres for the human eye, metres for large telescopes) an object of reasonable contrast to its surroundings some four thousand miles in diameter (such as the Australian land mass) would be visible to the unaided eye from the moon. But the Great Wall is of course not a disc but more like a thread, and a thread a foot long would not be visible from a hundred yards away, even though a human head is.

See also

- Defense of the Great Wall

- Great Wall of China hoax

- Great Wall of China Marathon

- List of walls

- Badaling

- Jumenbu

- Separation barrier

- Great Firewall of China

Further reading

- Roland Michaud (Photographer), Sabrina Michaud (Photographer), Michel Jan, The Great Wall of China (2001) ISBN 0-7892-0736-2

- Arthur Waldron, The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990.

- H.J.P Arnold, The Great Wall: is it or isn't it? Astronomy Now, 1995

References

External links

- Great Wall, Beijing, A Photographic Tour

- Photos of Great Wall in Simatai

- The Great Wall of China exhibition at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

- Great Wall Photos

- Great Wall: Ticket Price; Local Maps

- Travel Guide, historical information

Notes

¹ 10,000 li = 5,760 km (3,580 miles). In Chinese, 10,000 figuratively means "infinite", and the number should not be interpreted for its actual value, but rather as meaning the "infinitely long wall".

Gallery

-

Great Wall Summer 2006

-

Great Wall Summer 2006

-

Great Wall Roof Carvings