Donetsk

Donetsk

Донецьк / Донецк | |

|---|---|

Counter-clockwise: Cathedral Transfiguration of Jesus (big image), Donbass Palace, Drama Theatre, Lenin Square, bridge on Ilicha Prospect, Opera Theatre | |

| Coordinates: 48°00′10″N 37°48′19″E / 48.00278°N 37.80528°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Municipality | |

| Founded | 1869[1] |

| City rights | 1917 |

| Capital of Donetsk People's Republic | 2014 |

| Raions | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (Holova) | Oleksandr Lukyanchenko[a] |

| Area | |

| 358 km2 (138 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 169 m (554 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2016) | |

| 929,063 | |

| • Density | 2,600/km2 (6,700/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,009,700[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EET) |

| Postal code | 83000 — 83497 |

| Area code(s) | +380 622, 623 |

| Licence plate | АН |

| Sister cities | Bochum, Charleroi, Kutaisi, Pittsburgh, Sheffield, Taranto, Moscow, Vilnius |

| Climate | Dfb |

| ^ Donetsk was founded in 1869 as a workers settlement Yuzovka around the metallurgical factory of Welshman John Hughes. The settlement was established in lands of Yevdokim Shydlovsky who received them upon destruction of the Zaporizhian Sich in 1775. ^ The population of the metropolitan area is from 2004. | |

Donetsk (Template:Lang-uk [dɔˈnɛtsʲk]; Template:Lang-ru [dɐˈnʲɛtsk]; former names: Aleksandrovka, Hughesovka, Yuzovka, Stalino (see also: cities' alternative names)) is an industrial city in Ukraine on the Kalmius River. The population was estimated at 929,063 (2016 est.)[1] in the city, and over 2,000,000 in the metropolitan area (2011). According to the 2001 Ukrainian Census, Donetsk was the fifth-largest city in Ukraine.[2]

Administratively, it has been the centre of Donetsk Oblast, while historically, it is the unofficial capital and largest city of the larger economic and cultural Donets Basin (Donbass) region. Donetsk is adjacent to another major city of Makiivka and along with other surrounding cities forms a major urban sprawl and conurbation in the region. Donetsk has been a major economic, industrial and scientific centre of Ukraine with a high concentration of heavy industries and a skilled workforce.

The original settlement in the south of the European part of the Russian Empire was first mentioned as Aleksandrovka in 1779, under the Russian Empress Catherine the Great. In 1869, Welsh businessman, John Hughes, built a steel plant and several coal mines in the region; the town was named Yuzovka (Юзовка) in recognition of his role ("Yuz" being a Russian-language approximation of Hughes). During Soviet times, the city's steel industry was expanded. In 1924, it was renamed Stalino, and in 1932 the city became the centre of the Donetsk region. Renamed Donetsk in 1961, the city today remains the centre for coal mining and steel industry.

Since April 2014, Donetsk and its surrounding areas have been one of the major sites of fighting in the ongoing Donbass War, as pro-Russian separatist forces have battled against Ukrainian military forces for control of the city and surrounding areas. Throughout the war, the city of Donetsk has been administered by the pro-Russian separatist forces, with outlying territories of the Donetsk region being divided between the two sides.[3] Donetsk International Airport became the epicenter of the war with almost a -year-long battle leading to massive casualties among civilians and a total ruination of the northeastern neighborhoods of the city.

On June 27, 2014, the unrecognized nation of South Ossetia officially recognized the independence of the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) from Ukraine.[4]

As of May 8, 2018, the DPR has full control of the city, with Ukrainian and DPR forces still engaging in combat outside of the city.

History

Foundation

The city was founded in 1869 when the Welsh businessman John Hughes built a steel plant and several coal mines at Aleksandrovka, in the south of the European part of Russia. It was initially named Hughesovka (Template:Lang-ru).[5] In its early period, it received immigrants from Wales, especially from the town of Merthyr Tydfil.[6] By the beginning of the 20th century, Yuzovka had approximately 50,000 inhabitants,[7] and attained the status of a city in 1917.[8] The main district of "Hughezovka" is named English Colony, and the British origin of the city is reflected in its layout and architecture.

Soviet Union

When the Russian Civil War broke out, on 12 February 1918 Yuzovka was part of the Donets-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic. The Republic was disbanded at the 2nd All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets on 20 March 1918 when the independence of the Soviet Ukraine was announced. It failed to achieve recognition, either internationally or by the Russian SFSR, and, in accordance with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, was abolished.

In 1924, under Soviet rule, the city's name was changed to Stalin. In that year, the city's population totaled 63,708, and in the next year, 80,085. In 1929–31 the city's name was changed to Stalino.[9] The city did not have a drinking water system until 1931, when a 55.3 km (34.4 mi) system was laid underground. In July 1933, the city became the administrative center of the Donetsian Oblast of the Ukrainian SSR.[8] In 1933, the first 12 km (7 mi) sewer system was installed, and next year the first exploitation of gas was conducted within the city. In addition, some sources[which?] state that the city was briefly called Trotsk—after Leon Trotsky—for a few months in 1923.

At the beginning of World War II, the population of Stalino consisted of 507,000, and after the war, only 175,000. The German invasion during World War II almost completely destroyed the city, which was mostly rebuilt on a large scale at the war's end. It was occupied by German and Italian forces as part of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine between 16 October 1941 and 5 September 1943.

In 1945, young men and women aged 17 to 35, from the Danube Swabian (Schwowe) communities of Yugoslavia, Hungary and Romania (the Batschka and Banat), were forcibly sent to Russia as Allied "war reparations", being put to work as slave labour to rebuild Stalino and to work in its mines. The conditions were so poor that many died from disease and malnutrition.[10]

During Nikita Khrushchev's second wave of destalinization in November 1961, the city was renamed Donetsk, after the Seversky Donets River, a tributary of the Don[8] in order to distance it from the former leader Joseph Stalin.

In 1965, the Donetsk Academy of Sciences was established as part of the Academy of Science of the Ukrainian SSR.

Independent Ukraine

After experiencing a tough time in the 1990s, when it was the center of gang wars for control over industrial enterprises, Donetsk modernised quickly, largely under the influence of big companies.

In 1994 a referendum took place in the Donetsk Oblast and the Luhansk Oblast, with around 90% supporting the Russian language gaining status of an official language alongside Ukrainian, and for the Russian language to be an official language on a regional level; however, the referendum was annulled by the Kiev government.[11][12][unreliable source?]

In the 1990s and the 2000s coal mine collapses took place in Donetsk and the region, taking the lives of hundreds; those included the 2008 Ukraine coal mine collapse, the 2007 Zasyadko mine disaster, and the 2015 Zasyadko mine disaster. Ukraine has had a series of mining accidents since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and one reason being given is the linking of miners' pay to production, which serves as an incentive to ignore safety procedures that would slow production.[13]

In a summit in Moscow in 2008, Donetsk was recognised as the best city in the Commonwealth of Independent States for its implemented development strategies;[14] in 2012 and 2013 Donetsk was recognised as the best place for business in Ukraine.[15][16][17]

Whilst getting praise for its business potential, Donetsk also received criticism for the strong mafia connection of its business magnates, and for the increasing poverty rate (alongside a growing number of oligarchs).[18] Some analysts warned of a long-term collapse of the Donetsk economy, and that it could share Detroit's gloomy fate, due to its failure to combat crime and poverty[19][better source needed]

Euromaidan, War in Donbass, and Capital of the Donetsk People's Republic (2014-present)

After President Yanukovych abandoned Ukraine for Russia, Russian-backed defenders took over the main government building in Donetsk. The police did not offer resistance.[20] Later in the week the authorities of Donetsk denounced a referendum on the status of the region[21] and the police retook the Donetsk Oblast administrative building.[22][23] Donetsk became one of the centers of the 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine.

On 7 April 2014, pro-Russian activists seized control of Donetsk's government building and declared the "Donetsk People's Republic",[24] asking for Russian intervention.[25]

On 11 May 2014, a Donetsk status referendum, 2014 was held in Donetsk in which voters could choose political independence. It was stated by the head of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic election commission, Roman Lyagin, that almost 90 percent of those who voted in the Donetsk Region endorsed political independence from Kyiv. Ukraine does not recognize the referendum, while the EU and US stated that the polls were illegal.[26]

Heavy shelling by the Ukrainian Army and paramilitary units have caused civilian fatalities in Donetsk.[27][28][29] Human Rights Watch has called on both warring factions to cease using BM-21 Grad in populated areas, and has said the use of these weapons systems may be a violation of international humanitarian laws and could constitute war crimes.[30]

The 2015 IIHF World Championship Division I was scheduled for 18 to 24 April 2015 in Donetsk, but Ukraine withdrew as the tournament hosts due to the ongoing issues in the country.[31]

To celebrate the independence of the Donetsk People's Republic, in 2015 Donetsk was the venue for a major rock concert called Novorossiya-Rock, attracting such notable Russian language artists as Vadim Samoylov (ex-Agatha Christie), Chicherina, and 7B.[32][33][34]

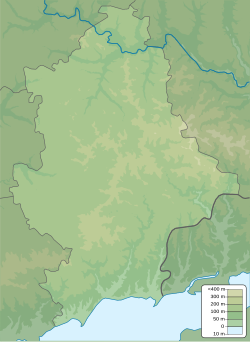

Geography

Donetsk lies in the steppe landscape, surrounded by scattered woodland, hills, spoil tips, rivers and lakes. The northern outskirts are mainly used for agriculture. The Kalmius River links the city with the Sea of Azov, which is 95 km (59 mi) to the south, and a popular recreational area for those living in Donetsk. A wide belt of farmlands surrounds the city.

The city stretches 28 km (17 mi) from north to south and 55 km (34 mi) from east to west. There are 2 nearby reservoirs: Nyzhnekalmius (60 ha), and the "Donetsk Sea" (206 ha). 5 rivers flow through the city, including the Kalmius, Asmolivka (13 km), Cherepashkyna (23 km), Skomoroshka and Bakhmutka. The city also contains a total of 125 spoil tips.[35]

Climate

Donetsk's climate is moderate warm summer continental (Köppen: Dfb).[36] The average temperatures are−4.1 °C (25 °F) in January and 21.6 °C (71 °F) in July. The average number of rainfall per year totals 162 days and up to 556 millimetres per year.[37]

| Climate data for Donetsk 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

1.3 (34.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.7 (19.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26.0) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−28.5 (−19.3) |

−32.2 (−26.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

34 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

46 (1.8) |

65 (2.6) |

51 (2.0) |

37 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

38 (1.5) |

41 (1.6) |

492 (19.4) |

| Average rainy days | 11 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 134 |

| Average snowy days | 17 | 17 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 72 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 84 | 77 | 66 | 62 | 66 | 64 | 60 | 67 | 76 | 86 | 88 | 73 |

| Source: Pogoda.ru.net[38] | |||||||||||||

Government and administrative divisions

Donetsk is the Capital of the Donetsk People's Republic.

Since 7 April 2014 Donetsk is de facto governed by the Donetsk People's Republic, even though it has only been recognized by the Republic of South Ossetia as of October 2014.

The territory of Donetsk is divided into 9 administrative raions (districts), whose local government is administered by raion councils, which are subordinate to the Donetsk City Council.

|

Demographics

See article: Russians in Ukraine

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897[39] | 28,100 | — |

| 1926[40] | 106,000 | +277.2% |

| 1939[41] | 466,300 | +339.9% |

| 1959[42] | 699,200 | +49.9% |

| 1970[43] | 879,000 | +25.7% |

| 1979[44] | 1,020,800 | +16.1% |

| 1989[45] | 1,109,100 | +8.7% |

| 1998[46] | 1,065,400 | −3.9% |

| 2006[47] | 993,500 | −6.7% |

| 2011 | 975,959 | −1.8% |

| 2015 | 933,795 | −4.3% |

Donetsk had a population of over 985,000 inhabitants in 2009[48] and over 1,566,000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area in 2004. It was the fifth-largest city in Ukraine.[2]

According to the 2001 census, the Donetsk Oblast is inhabited by members of more than 130 ethnic groups.[49] The Ukrainian ethnicity is 56.9% of the population (2,744,100 people); the Russian ethnicity is 38.2% of the population (1,844,400 people).[49] The native language of 74.9% of the population of the Donetsk region is Russian, compared with 24.1% Ukrainian.[50] 58.7% of people of Ukrainian ethnicity considered Russian to be their native language.[50] Out of 4.5 million residents of the Donetsk region, 550 are Russian citizens.[51]

In 1989 there were no Ukrainian language schools in Donetsk.[52]

The structure of the Donetsk City Municipality by ethnicity is as follows:[53]

- Russians: 493,392 people, 48.15%

- Ukrainians: 478,041 people, 46.65%

- Belarusians: 11,769 people, 1.15%

- Pontic Greeks (including Caucasus Greeks): 10,180 people, 0.99%

- Jews: 5,087 people, 0.50%

- Tatars: 4,987 people, 0.49%

- Armenians: 4,050 people, 0.40%

- Azerbaijanis: 2,098 people, 0.20%

- Georgians: 2,073 people, 0.20%

- Other: 13,001 people, 1.27%

- Total: 1,024,678 people, 100.00%

In 1991 one-third of the population identified as Russian, one-third as Ukrainian while the majority of the rest declared themselves Slavs.[52] Smaller minorities include in particular ethnic groups from the South Caucasus and northeast Anatolia region, including Armenians, Georgians, and Pontic Greeks (including those defined as Caucasus Greeks).

Native language of the population of the city of Donetsk as of the Ukrainian Census of 2001:[54]

- Russian 87.8%

- Ukrainian 11.1%

- Armenian 0.1%

- Belarusian 0.1%

Economy

This section needs to be updated. (June 2012) |

Donetsk and the surrounding territories are heavily urbanised and agglomerated into conurbation. The workforce is heavily involved with heavy industry, especially coal mining. The city is an important center of heavy industry and coal mines in the Donets Basin (Donbass). Directly under the city lie coal mines, which have recently seen an increase in mining accidents, the most recent accident being at the Zasyadko mine, which killed over 100 workers.[55]

Donetsk's economy consists of about 200 industrial organizations that have a total production output of more than 120 billion rubles per year and more than 20,000 medium-small sized organizations.[56] The city's coal mining industry comprises 17 coal mines and two concentrating mills; the metallurgy industry comprises 5 large metallurgical plants located throughout the city; the engineering market comprises 67 organizations, and the food industry — 32 organizations.[56]

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Donetsk and other neighboring cities of the Donbass suffered heavily, as many factories were closed down and many inhabitants lost their jobs.[57] About 412,000 square metres (4,434,731 sq ft) of living space, 7.9 km (4.9 mi) of gas networks, and 15.1 km (9.4 mi) of water supply networks were constructed in the city during 1998–2001.[56]

The city also houses the "Donetsk" special economic zone.[56][58] Donetsk currently has nine sister cities.[59] The German city of Magdeburg had economic partnerships with Donetsk during 1962–1996.[60][61]

In 2012, Donetsk was rated the best city for business in Ukraine by Forbes. Donetsk topped the rating in five indicators: human capital, the purchasing power of citizens, investment situation, economic stability, as well as infrastructure and comfort.[62]

The shopping areas in the city include the enclosed shopping mall Donetsk City.

Sports

Donetsk is a large sports center, has a developed infrastructure, and has repeatedly held international competitions – Davis Cup, UEFA Champions League. Representatives of the city are state leaders sports such as football, hockey, basketball, boxing, tennis, athletics and others.

The most popular sport in Donetsk is football. Donetsk is the home to three major professional football clubs: Shakhtar Donetsk, which plays at the Donbass Arena (previously at the Shakhtar Stadium and the RSC Olimpiyskiy), Metalurh Donetsk, which plays at the Metalurh Stadium, and FC Olimpik Donetsk. All three play in the Ukraine Premier League. Shakhtar Donetsk won the Ukrainian Championship and Ukrainian Cup multiple times, and in 2009 they became the second team from Ukraine (after FC Dynamo Kyiv) to win a European competition, the UEFA Cup. Donetsk is also home to the women's football club WFC Donchanka, one of the most successful clubs in the history of the Ukrainian Women's League.

Donetsk is home to the football stadium Donbass Arena, which was opened in 2009. It became the first stadium in Eastern Europe designed and constructed according to the UEFA standards for stadiums of "Elite" category. When the joint bid for the UEFA Euro 2012 was won by Poland and Ukraine, Donetsk's Donbass Arena was chosen as the location for three Group D matches, one quarter-final match, and one semi-final match.[63] The RSK Olimpiyskyi Stadium was chosen as a reserve stadium.[64]

Donetsk, together with the nearby Mariupol, were the host towns of the 2009 UEFA European Under-19 Championship. The stadiums hosting the event on behalf of Donetsk were RSC Olimpiyskiy (which hosted the final) and the Metalurh Stadium.

Donetsk is home to the ice hockey club HC Donbass, playing at the Druzhba Arena since 2011, which won the 2011 Ukrainian national champion, and which is the only elite level team in the country. After playing a single season in the Russian Major League, the club upgraded its arena to Kontinental Hockey League regulations, and joined the league in 2012. When moving to the KHL, the club created a local farm club to play in the Ukrainian Championship under the name HC Donbass-2, which won the 2012 and 2013 national titles. In 2013 Donetsk was hosting the 2012–13 IIHF Continental Cup ice hockey Super Final, which HC Donbass won, and the 2013 IIHF World Championship Division I – Group B, where Ukraine finished 1st and earned promotion to Group A (both were hosted at the Druzhba Arena).

Donetsk is also home to the basketball club BC Donetsk, which plays in the Ukrainian Basketball Super League, and won the 2012 champion title. The club is playing at the Druzhba Arena. Donetsk was chosen as one of the 6 cities to host the FIBA EuroBasket 2015.

The city used to be the home of few notable at the time yet now defunct clubs. The MFC Shakhtar Donetsk club won the Ukrainian futsal championship five times, but was dissolved in January 2011 midway through the season due to financial problems (at the time – the most titled club in Ukraine). One of the top Soviet volleyball teams at the time, VC Shakhtar Donetsk, who were the last team to win the Soviet Volleyball Championship, in 1992. The team also won the first two championships in the independent Ukraine league, in 1992 and 1993 (the 1992 Ukraine championship was held in Donetsk), and won the Ukraine Cup in 1993, but after having financial issues, the club was relegated in 1997, and after one season in the second tear it was shut down.

Donetsk hosted the USSR Tennis Championship in 1978, 1979 and 1980, and hosted some tennis matches of the 2005 Davis Cup. Donetsk was home to the Alexander Kolyaskin Memorial, which was held between 2002–2008 and part of the ATP Challenger Series, and Donetsk is the home of the female Viccourt Cup, which is classified as an ITF Women's Circuit and started in 2012.

Donetsk was always an important athletics centre, and hosted various events. Donetsk was one of the host towns for the 1978 and 1980 Soviet Athletics Championships, and was the sole host town of the event in 1984. Donetsk also hosted the 1977 European Athletics Junior Championships. The stadium used for those athletics events was the RSC Olimpiyskiy (at the time called RSC Lokomotiv).

Among the different track and field sports, Donetsk especially has a big name in pole vaulting. Serhii Bubka, regarded by many as the greatest pole vaulter in history, grew up in the city, and also started in 1992 an annual pole vaulting event in Donetsk, called Pole Vault Stars. Bubka himself set the world indoor record at the event three times (1990, 1991, 1993). His indoor world pole vault record of 6.15m, set in the Donetsk Olympic Stadium on 21 February 1993, was not broken until 2014. The Russian female pole vaulter Yelena Isinbayeva set a new world record at the event every year between 2004–2009.

The 2015 IIHF World Championship Division I ice hockey tournament had been scheduled for 18 to 24 April 2015 in Donetsk but was later moved to Kraków, Poland due to the ongoing war.

Professional sports teams

The following is a list of existing professional sports teams, and notable (title-winning) defunct clubs:

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC Shakhtar Donetsk | Ukrainian Premier League | Association football | Donbass Arena | 1936 | 13 |

| FC Metalurh Donetsk | Ukrainian Premier League | Association football | Metalurh Stadium | 1996 | 0 |

| FC Olimpik Donetsk | Ukrainian Premier League | Association football | Sports Complex Olimpik | 2001 | 0 |

| WFC Donchanka | Ukrainian Women's League | Women's association football | TsPOR Donchanka Stadium | 1992 | 5 |

| MFC Shakhtar Donetsk (defunct) | Ukrainian Futsal Championship | Futsal | Pavilion | 1998 | 5 |

| Shakhtar-Academiya | Ukrainian Handball Super League | Handball | SC Tekstilshik | 1983 | 3 |

| HC Donbass | Kontinental Hockey League | Ice hockey | Druzhba Arena | 2005 | Ukraine: 4 (2 as affiliate HC Donbass-2) |

| BC Donetsk (defunct) | Ukrainian SuperLeague | Basketball | Druzhba Arena | 2006 | 1 |

| VC Shakhtar Donetsk (defunct) | Ukrainian Volleyball Championship | Volleyball | Druzhba Arena | 1983 | Soviet Union: 1 Ukraine: 2 |

Culture

Main sights

First Line Avenue (Artema Street)

First Line Avenue, also known as Artema Street, is considered to be the main part of Donetsk. It generally functions as the foremost place to start for any tourist trip around the city. The street hosts a mix of new and old architecture together with small parks, stylish hotels, shopping centres and restaurants. Noteworthy sites include Lenin Square, the Opera & Ballet Theatre, Monument to Coalminers and Donetsk Drama Theatre.

Statue of Artem (Fyodor Sergeyev)

This imposing six-metre statue on Artema Street is a tribute to one of the most celebrated Soviet politicians. After his death in the Donets Basin in 1921, Joseph Stalin adopted his son.

Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theatre

Built in 1936, the Donetsk Opera and Ballet Theatre, is a gem of a theatre with an elegant exterior and world-class performances inside. Donetsk is the home to the Donetsk Ballet company since 1946.

Donbass Palace

This 5-star hotel in the center of Donetsk is the only ex-Ukrainian hotel to join The Leading Hotels of The World and was Ukraine's leading business hotel according to the World Travel Awards Association. It was built in 1938 upon the project of Shuvalova and Rechanikov. During the Nazi occupation of Donetsk, the Gestapo headquartered in the former hotel; the building was partially destroyed during the war. The hotel was opened after the reconstruction in 2004.

Pushkin Boulevard

A green walkway that takes walkers away from Donetsk city life for a 2 km (1.24 mi) stroll. Here there are fountains, al fresco cafes and a number of statues such as the monument to Taras Shevchenko.

Donetsk is home to the world's perhaps most famous plant forged out of steel,[citation needed] the intricate Mertsalov Palm, located on Pushkin Boulevard. Originally created for an exhibition in 1896 by Aleksei Mertsalov, a local blacksmith, out of a single rail, it represented the skills and power of the heavy industry in Czarist Russia.

Monument to John Hughes

This 2001 statue located in front of Donetsk National Technical University honours the hard work of Welsh city founder John James Hughes. He was responsible for the city's Yuzovka Steel Plant that gave Donetsk its industrial history.

Forged Figures Park

Forged Figures Park was opened in 2001 and is one-in-a-kind object. International Smithcraft Festival takes place in the park every year. The most impressive masterworks remain in the city as a gift expanding the number of park's "residents"

Aquapark

Donetsk Aquapark "Royal Marine" was opened in Scherbakova Park in early winter 2012 and, according to experts' estimates, is one of the top aquaparks in Europe. The free-standing dome, made with OpenAire's exclusive, maintenance-free aluminium truss structure, will be 26 metres (85 ft) high with a diameter of 85 metres (279 ft), and feature a unique retractable design that slides open in a smooth rotating motion, opening up to 50% of the structure to sunlight and fresh air. The 5,700-square-metre (61,000 sq ft) Aquatoria, slated to become the largest retractable aluminium-domed indoor waterpark in the world, is being built by Canadian company OpenAire, Inc., a premier designer, manufacturer and installer of retractable roof enclosures and operable skylights.[65]

Architecture

Donetsk, at the time Yuzovka, was divided into two parts: north and south. In the southern part were the city's factories, railway stations, telegraph buildings, hospitals and schools. Not far from the factories was the English colony where the engineers and the management lived. After the construction of the residence of John Hughes and the various complexes for the foreign workers, the city's southern portion was constructed mainly in the English style.

These buildings used rectangular and triangular shaped façades, green rooftops, large windows, which occupied a large portion of the building, and balconies. In this part of the town, the streets were large and had pavements. A major influence on the formation of architecture in Donetsk was the official architect of a Novorossiya company — Moldingauyer. Preserved buildings of the southern part of Yuzovka consisted of the residences of John Hughes (1891, partially preserved), Bolfur (1889) and Bosse.

In the northern part of Yuzovka, Novyi Svet, lived traders, craftsmen and bureaucrats. Here were located the market hall, the police headquarters and the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of Jesus. The central street of Novyi Svet and the neighbouring streets were mainly edged by one- or two-story residential buildings, as well as markets, restaurants, hotels, offices and banks. A famous preserved building in the northern part of Yuzovka was the Hotel Great Britain.

The first general plan of Stalino was made in 1932 in Odessa by the architect P. Golovchenko. In 1937, the project was partly reworked. These projects were the first in the city's construction bureau's history.

A large portion of the city's buildings from the second half of the 20th century were designed by the architect Pavel Vigdergauz, which was given the Government award of the USSR for architecture in the city of Donetsk in 1978.

Religion

Donetsk's residents belong to religious traditions including the Eastern Orthodox Church[66] Eastern Catholic Churches, Protestantism, and the Roman Catholic Church, as well as Islam and Judaism.[67][68] The religious body with the most members is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate.

In 2014, a fake leaflet "signed by Chairman of Donetsk's temporary government Denis Pushilin" was distributed to Jews on the festival of Passover. The leaflet informed Donetsk's Jewish citizen to register themselves, their property, and their family to the pro-Russian authorities. The leaflet claimed that failure to comply with its demands would result in the revocation of citizenship and confiscation of property. The leaflet prompted confusion and fear among Donetsk's Jewish population, who saw echoes of the Holocaust in the leaflet.[69]

Media

Five television stations operate within Donetsk:

- TRK Ukraina (Template:Lang-uk)[70]

- KRT, Kyivska Rus' (Template:Lang-ua)[71]

- First Municipal (Template:Lang-ru)[72]

- Kanal 27 (Template:Lang-ru)

- TRK Donbass (Template:Lang-ru)

In Donetsk, there is the 360-metre tall TV tower, one of the tallest structures in the city, completed in 1992.

Notable people

The citizens of Donetsk are commonly called Donchyani (Template:Lang-ru). The following is a list of famous people who were born or brought up in the city:

- Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine's wealthiest businessman, founder of System Capital Management, No. 47 in Forbes' The World's Billionaires.

- Emma Andijewska, Ukrainian poet.

- Alexander Anoprienko, Professor of Computer Engineering

- Zalman Aran (Aharonovich), Israeli social-democratic politician, minister of education (1955–1960) and (1963–1969).

- Serhiy Arbuzov, head of Ukrainian Bank.

- Polina Astakhova, Ukrainian gymnast.

- Mykola Azarov, former Prime Minister of Ukraine

- Fyodor Berezin, Russian-language science fiction writer and Deputy Minister of Defence of the Donetsk People's Republic.

- Volodymyr Biletskyy, Ukrainian scientist.

- Serhii Bubka, Ukrainian pole vault athlete; Olympic Games champion: 1988; World Champion: 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, European Champion: 1986; Champion of the USSR: 1984, 1985.

- Viktor Burduk, an artist, a blacksmith.

- Vera Filatova, actress.

- Yuriy Dehteryov, Soviet goalkeeper.

- Anatoly Timofeevich Fomenko, Russian Mathematician and lecturer at the Moscow University. Promoter of New Chronology.

- Yuriy Gavrilov, Volleyball player, Olympic gold medallist.

- Dmytro Gnap, journalist, investigating corruption.

- Yuri Kara, Russian film director and producer.

- Yevgeny Khaldei, Soviet photographer.

- Nikita Khrushchev, General Secretary of the CPSU and Premier of the Soviet Union 1953–1964 (born in Kalinovka, Kursk Oblast, Russia but grew up in Yuzovka).

- Valeriy Konovalyuk, an economist and businessman.

- Tatyana Kravchenko, Soviet and Russian actress.

- Mikhail Krichevsky, the last surviving World War I veteran who fought for the Russian Empire.

- Alexander Kuzemsky - Soviet and Russian theoretical physicist.

- Aleksandr Lebziak, Russian boxer.

- Make Me Famous - English language Metalcore band.

- Natalya Mammadova, Azeri volleyball player.

- Oleksiy Matsuka, corruption investigator, Reporters Without Borders named Matsuka in its list of 100 Information Heroes.

- Siouzana Melikián, a Russian-Mexican actress.

- Evgenij Miroshnichenko, Ukrainian chess player.

- Master SheFF, the leader of Bad Balance and creator of Russian hip hop.

- Ilya Mate, Olympic champion in 1980.

- Oleksiy Pecherov, a Ukrainian basketball player.

- Vadim Pisarev, Ukrainian dancer and art Director of Donetsk State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre named after Solovyanenko.

- Lilia Podkopayeva, a Ukrainian gymnast, and the 1996 Olympic All Around Champion

- Sergiy Rebrov, footballer.

- Aleksandr Revva, comedian.

- Volodymyr Rybak, Mayor of Donetsk and Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada.

- Vladislav Adolfovitch Rusanov, Russian-language science fiction writer and chairman of the Donetsk People's Republic Writer's Union.

- Denis Shaforostov, Ukrainian musician, vocalist for Asking Alexandria

- Natan Sharansky, former Soviet dissident, anticommunist, Zionist, Israeli politician and writer.

- Oleg Stefan, Russian actor.

- Anatoliy Solovyanenko, Soviet opera singer.

- Viktor Smyrnov, Paralympic swimmer.

- Viktor Sidyak, fencing, first Soviet individual sabre Olympic gold medal in Munich 1972, multiple times winner of World Championships and Olympic medalist (1968, 1972, 1976 and 1980).

- Vasyl Stus, Ukrainian poet and publicist, one of the most active members of Ukrainian dissident movement.

- Petro Symonenko, head of the Communist Party of Ukraine.

- Ihor Sorkin, head of the Ukrainian National Bank.

- Kirill Borisovich Tolpygo, Soviet physicist.

- Nadezhda Tkachenko, Olympic-gold winning pentathlete.

- Marina Tsvigun, religious sect leader, new age movement.

- Oleg Tverdovsky, ice hockey player.

- Kirill Borisovich Tolpygo, Soviet physicist and a Corresponding Member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- Alexander Yagubkin, boxer.

- Viktor Yanukovych, former president of Ukraine; deposed due to the Euromaidan Revolts of 2013–2014.[73]

- Oleg Vernyayev, Gymnast, Olympic gold medallist.

- Pavlo Vigderhaus, Soviet architect, Monument to a Miner creator.

- Vladimir Grigoryevich Zakharov, Soviet composer.

Museums

Donetsk is home to about 140 museums. Among them, two large regional museums – Donetsk Region History Museum and Donetsk Regional Art Museum.

Donetsk Region History Museum reveals the city's true identity and covers to the entire local community, diverse as it is. Set up in 1924, it offers an extensive expo with 120,000 exhibits: from archeological findings dating back to pre-historic times to the founding of the city by John Hughes, development of industry and coal mining, World War II and the Soviet times. On 21 August 2014, the mayor of Donetsk reported that the roof and walls of the Donetsk Regional History Museum had been destroyed by shellfire early that morning.[74]

FC Shaktar Museum was opened in 2010. This museum was the first Ukrainian museum to be nominated for a European Museum of the Year Award[75]

Transport

Local transport

The main forms of transport within Donetsk are: trams, electric trolley buses, buses and marshrutkas (private minibuses). The city's public transport system is controlled by the united Dongorpastrans municipal company. The city has 12 tram lines (~130 km), 17 trolley bus lines (~188 km), and about 115 bus lines.[76] Both the tram and trolley bus systems in the city are served by 2 depots each.[76] Another method of transport within the city is taxicab service, of which there are 32 in Donetsk.

The city also contains autostations located within the city and its suburbs: autostation Yuzhny (South), which serves mainly transport lines to the south, hence its name; autostation Tsentr (Centre), which serves transport in the direction of Marinka and Vuhledar as well as intercity transport; the autostation Krytyi rynok (Indoor market), which serves mainly transport in the north and east directions; and the autostation Putilovsky, which serves mainly the north and northwest transport directions.

The construction of the metro system in the city, begun in 1992, was recently abandoned due to the lack of funding. No lines or stations have been finished.[77]

Railways

Donetsk's main railway station, which serves about 7 million passengers annually,[76] is located in the northern part of the city. There is a museum near the main station, dealing with the history of the region's railways. Other railway stations are: Rutchenkovo, located in the Kyivskyi Raion; Mandrykino (Petrovskyi Raion), and Mushketovo (Budionivskyi Raion). Some passenger trains avoid Donetsk station and serve the Yasynuvata station, located outside the city limits. Although not used for regular transport, the city also has a children's railway. (As of September 2009) a new railway terminal facility that will comply with UEFA requirements (since Donetsk is one of the host city's for UEFA EURO 2012) is planned.[78]

The Donetsk Oblast was an important transport hub in Ukraine, so was its centre Donetsk. The Donetsk Railways, based in Donetsk, is the largest railway division in the Republic. It serves the farming and industrial businesses of the area, and the populations of the Donetsk and Lugansk Republics and parts of the Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhia and Ukrainian Kharkiv oblasts.

Road transport

The ![]() highway, part of the International E-road network, runs through the city en route to Rostov-on-Don in Russia.

highway, part of the International E-road network, runs through the city en route to Rostov-on-Don in Russia.

In addition, another international road runs through the city: the M 04. Also, three national Ukrainian roads (N 15, N 20, and N 21) pass through the city.

The construction of the fourth stage of a circular road bypassing Donetsk is to be completed in 2014.[79]

Air travel

In addition to public and rail transport, Donetsk has an international airport.[80] It was constructed during the early 1940s and early 1950s. It was rebuilt in 1973 and again from 2011 to 2012. Because of fighting the airport has been closed as of 26 May 2014 and the airport has since then largely been destroyed.[81] The airspace above Donetsk has also been closed since the MH17 disaster.

Education

Donetsk has several universities, which include five state universities, 11 institutes, three academies, 14 technicums, five private universities, and six colleges.

The most important and prominent educational institutions include Donetsk National Technical University, founded in 1921[82] ("Donetsk Polytechnical Institute" in 1960–1993), as well as the Donetsk National University[83] which was founded in 1937. The National Technical University held close contacts with the University in Magdeburg. Since 1970, more than 100 students from Germany (East Germany) have completed their higher education at either one of the two main universities in Donetsk. Donetsk is also the home of the Donetsk National Medical University, which was founded in 1930 and became one of the largest medical universities in the Soviet Union. There are also several scientific research institutes and an Islamic University within Donetsk.

Donetsk is also the home of the Prokofiev Donetsk State Music Academy, a music conservatory founded in 1960.

Twinnings

Donetsk participates in international town twinning schemes to foster good international relations. Partners include:

|

See also

- Donetsk People's Republic

- List of airports in Ukraine

- List of the busiest airports in the former USSR

- Russians in Ukraine

Notes

- ^ Due to the War in Donbass, Lukyanchenko was forced to move to Kiev.

References

- ^ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Results / General results of the census / Number of cities". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Weaver, Matthew; Luhn, Alec (13 February 2015). "Ukraine ceasefire deal agreed at Minsk talks". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ News, Tass (27 June 2014). "South Ossetia recognizes independence of Donetsk People's Republic". TASS. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Yuz is a Russian or Ukrainian approximation of Hughes

- ^ Evans, Martin (11 June 2012). "Euro 2012: Donetsk's roots have more in common with Merthyr Tydfil than Moscow". Telegraph. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ The population included mostly migrants from neighbouring Russian territories

- ^ a b c Из истории города [From the history of the city]. Official site of the Head of Donetsk City (in Russian). 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://alldonetsk.info/en/history-city-donetsk The history of the city of Donetsk

- ^ "Das politische Bewusstsein" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Morin, Yevgenii (12 May 2014). Донбасс: забытый референдум-1994 [Donbass: the forgotten 1994 referendum]. The Kiev Times (in Russian). Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Киев уже 20 лет обманывает Донбасс: Донецкая и Луганская области еще в 1994 году проголосовали за федерализацию, русский язык и евразийскую интеграцию [Kiev has been cheating Donbass for 20 years: in 1994 the Donetsk and Lugansk regions voted in favour of federalisation, the Russian language, and Eurasian integration] (in Russian). Nakanune.ru. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine's mine death toll rises". BBC News. 20 November 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Донецк признан лучшим городом СНГ [Donetsk named best city of the CIS] (in Russian). Utro.ua. 8 April 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Донецк признали лучшим городом для ведения бизнеса [Donetsk recognised as the best city for conducting business] (in Russian). Lb.ua. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Донецк второй год подряд признают самым привлекательным в Украине для бизнеса [Donetsk recognised as the most attractive for business in Ukraine for the second consecutive year] (in Russian). Gazeta.ua. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Донецк признали самым привлекательным городом для бизнеса - Forbes [Donetsk recognised as the most attractive city for business - Forbes] (in Russian). Epravda.com.ua. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Kommodova, Natalia (4 August 2009). 'Большие сдвиги' Донбасса, богатые летчики и бедные вундеркинды - Обзор донецкой прессы ['Great shifts' of Donbass, rich high fliers and poor wunderkind - Overview by the Donetsk Press] (in Russian). Ostro.org. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Почему Донецк ждет судьба Детройта [Why Donetsk awaits the fate of Detroit] (in Russian). Makeevkainfo.com.ua. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "В Донецке несколько сотен радикалов с криками "Россия" штурмуют ОГА". Gazeta.ua. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ "Новости Донбасса :: The authorities of Donetsk region don't want a referendum and they opposed 'foreign scenarios' – video report". Novosti.dn.ua. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Kushch, Lina (6 March 2014). "Ukrainian flag again flies over Donetsk regional HQ". Reuters. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Roth, Andrew (7 March 2014). "Ukrainian Officials in East Act to Blunt Pro-Russian Forces". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Russian Roulette: The Invasion of Ukraine (Dispatch Twenty Three). VICE News. 11 April 2014.

- ^ Radyuhin, Vladimir (7 April 2014). "Donetsk proclaims independence from Ukraine". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ukraine crisis: Eastern rebels claim 'self-rule' poll victory". BBC News. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Shells hit Donetsk amid Russia convoy row". BBC News. August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Kyiv's troops surround separatist stronghold Donetsk, civilian casualties high". Euronews. August 12, 2014.

- ^ "3 days in Donetsk: 70+ civilians killed, over 100 wounded". RT. August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: Unguided Rockets Killing Civilians Stop Use of Grads in Populated Areas". Human Rights Watch. July 24, 2014.

- ^ Steven Ellis (15 August 2014). "Ukraine Withdraws as Hosts of 2015 Division IA World Championships". The Hockey House.

- ^ В Донецке выступили Чичерина, Вадим Самойлов и 7Б [Chicherina, Vadim Samoylov, and 7B performed in Donetsk]. Korrespondent.net (in Russian). 24 April 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" В Донецке пройдут рок-концерты [Rock concerts will be held in Donetsk] (in Russian). Don-ua.com. 20 April 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Бывший участник "Агаты Кристи" Вадим Самойлов и певица Чичерина выступят в Донецке и Луганске [Former member of "Agatha Christie" Vadim Samoilov and singer Chicherina will perform in Donetsk and Lugansk]. NEWSru.com (in Russian). 21 April 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Liakh, Liudmila. Было ли гетто в Донецке? [Was there a ghetto in Donetsk?] (in Russian). gorod.donbass.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Donetsk, Ukraine Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "The Weather in Donetsk" Погода в Донецке. rospogoda.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Погода и Климат: Климат Донецка [Weather and Climate: Climate of Donetsk] (in Russian). pogoda.ru.net. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Statistics from the first All-Russian Empire Census, conducted on 28 January [O.S. 15 15 January] 1897

- ^ Statistics from the First All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 17 December 1926.

- ^ Statistics are from the All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 17 January 1939.

- ^ Statistics are from the All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 15 January 1959.

- ^ Statistics are from the All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 15 January 1970.

- ^ Statistics are from the All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 17 January 1979.

- ^ Statistics are from the All Union Census of the Soviet Union, conducted on 12 January 1989.

- ^ Statistics are from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, conducted on 1 January 1998.

- ^ Statistics are from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, conducted on 1 January 2006.

- ^ Чисельність населення на 1 березня 2009 року та середня за січень-лютий 2009 року [Population on 1 March 2009 and the average for January–February of 2009]. Department of Statistics of the Donetsk Region (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b 2001 Ukrainian Census, Численность и состав населения Донецкой области по итогам Всеукраинской переписи населения 2001 года [The size and composition of the population on the basis of the Donetsk region in the 2001 Census].

- ^ a b 2001 Ukrainian Census, Численность и состав населения Донецкой области по итогам Всеукраинской переписи населения 2001 года, Языковой состав населения Донецкой области, по данным Всеукраинской переписи населения [The size and composition of the population on the basis of the Donetsk region in the 2001 Census, Linguistic composition of the population of the Donetsk region, according to the Census]

- ^ Financial Times, Donetsk governor battles to restore order, by John Reed, 26/27 April 2014, p5.

- ^ a b Steele, Jonathan (1994). Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gorbachev, and the Mirage of Democracy. Harvard University Press. pp. 217–18. ISBN 978-0-674-26837-1. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Перепис населення: Донецька область: Національний склад та рідна мова населення Донецької області. Розподіл постійного населення за найбільш численними національностями та рідною мовою по міськрадах та районах [Census: Donetsk region: Ethnic composition and native language of the population of the Donetsk region. Distribution of the permanent population by the most numerous nationalities and native language by councils and districts]. Department of Statistics of the Donetsk Region (in Ukrainian). 2004. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About number and composition population of Donets'k Region by data, All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". State Statistical Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Another victim of Ukraine mine blast dies in hospital". RIA Novosti. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "?". lukyanchenko.dn.ua.[dead link]

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 613. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ^ Про спеціальні економічні зони та спеціальний режим інвестиційної діяльності в Донецькій області [On Special Economic Zones and Special Mode of Investment in the Donetsk oblast]. Order of Verhovna Rada (in Ukrainian). 24 December 1998. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Города побратимы Донецка [Sister cities of Donetsk]. Official site of the Head of Donetsk City (in Russian). 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stegers, Wolfgang (5 November 2013). "Meine Reise nach Donetsk I: Die unbekannte ukrainische Metropole" [My trip to Donetsk I: The unknown Ukrainian metropolis]. wize.life (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ The Daily Review, Volume 13, Michigan 1967. 1967. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Forbes admitted Donetsk best city for business in Ukraine". Yellowpage.in.ua. 1 June 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stadiums / Donetsk". UEFA Euro 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stadiums / Introduction". UEFA Euro 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "World's largest retractable aluminum-domed waterpark under work in Ukraine". Themeparkpost.com. 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Донбасс Православный [Orthodox Donbass] (in Russian). ortodox.donbass.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy" Соціологічне опитування - Релігія: Віруючим якої церкви, конфесії Ви себе вважаєте? [Sociological survey - Religion: Believers, which churches do you consider yourself to adherents of?]. Razumkov Centre (in Ukrainian). 2006. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Yarosh, Oleg; Brylov, Denys (2011). "Muslim communities and Islamic network institutions in Ukraine: contesting authorities in shaping Islamic localities". In Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowka (ed.). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowska. p. 254. ISBN 978-83-903229-5-7. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Margalit, Michal. "Donetsk leaflet: Jews must register or face deportation." Ynetnews. 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Television channel 'Ukraine' home". TRK Ukraina. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Main Page". Kyivska Rus (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Main Page". Pervyi munitsipal'nyi kanal (in Russian).[dead link]

- ^ "Ukraine: President Viktor Yanukovych says he was forced to flee due to threats; slams 'pro-fascist' forces – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Kishkovsky, Sophia (14 August 2014). "Eastern Ukraine's museums told to hide their collections". theartnewspaper.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "FC Shakhtar Museum nominated for an 'Oscar'". Donbass-arena.com. 19 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Транспорт [Transport]. Partner-Portal (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ У Донецьку припиняють зводити метро [Metro construction in Donetsk is stopping]. 1tv.com.ua (in Ukrainian). 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Construction of railway terminal in Donetsk for UEFA EURO 2012 worth UAH 414mln". Ukrinform. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Building of fourth stage of Donetsk ring road to end in 2014, Interfax-Ukraine (11 January 2014)

- ^ "Service Center, International Airport 'Donetsk'". VIP-Terminal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Loiko, Sergei L. (28 October 2014). "Ukraine fighters, surrounded at wrecked airport, refuse to give up". Los Angeles Times. Donetsk. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About DonNTU". Donetsk National Technical University (DonNTU). 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "History of the University". Donetsk National University. 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

Sources

- Kilesso, S. (1982). Donetsk. Architectural-historical summary. Kyiv: Budivelnyk. p. 152.

- "Partner-Portal — Everything about Donetsk". Partner-Portal (in Russian). Интернет-агентство «Партнер». Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

General

- donetsk.org.ua — Donetsk city administration website Template:Uk icon/Template:Ru icon

- stroit.dn.ua — Construction site of Donetsk

- Template:Ru icon partner.donetsk.ua — Informational portal about Donetsk

- Official site of the Donetsk international airport

- Shakhtar Donetsk official website of the Shakhtar football team

- dntsk.net — old and recent photos of Donetsk Template:Ru icon

Historical

- geocities.com — History of Donetsk and the story of the founder John Hughes

- bfcollection.net — Historic images of Donetsk

- alldonetsk.info – The history of the city of Donetsk

- [3] - Language Sandarmokh of Donetchyna, Mariya Oliynyk (UKR)

Maps

- citylife.donetsk.ua — City map in English language for foreigners

- maps.google.com — Google maps satellite view of Donetsk

- wikimapia.org — Wikimapia view of Donetsk

- gorod.dn.ua — City map browsable and searchable by address

- Donetsk

- Cities in Donetsk Oblast

- Special economic zones

- Populated places established in 1869

- Mining cities and regions in Ukraine

- Cities of regional significance in Ukraine

- Populated places established in the Russian Empire

- 1869 establishments in the Russian Empire

- City name changes in Ukraine

- Former Soviet toponymy in Ukraine

- Oblast centers in Ukraine

- Populated places in the Donetsk People's Republic

- De-Stalinization