7th Infantry Division (United States)

| 7th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

The 7th Infantry Division's combat service identification badge | |

| Active | 1917–1921 1940–1971 1974–1994 1999–2006 2012–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Stryker infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, U.S. |

| Nickname(s) | "Hourglass Division", "Bayonet Division", "California Division"[1] |

| Motto(s) | Light, Silent, and Deadly |

| March | "Arirang" |

| Mascot(s) | Black Widow spider |

| Engagements | World War I Korean War |

| Website | Official Website |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | MG Willard M. Burleson III[2] |

| Notable commanders | Charles H. Corlett Archibald V. Arnold Joseph Warren Stilwell, Jr. Lyman Lemnitzer Arthur Trudeau Hal Moore Wayne C. Smith William H. Harrison |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (1973-2015)[3] |  |

The 7th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army. Today, it exists as a unique 250-man administrative headquarters based at Joint Base Lewis-McChord overseeing several units, though none of the 7th Infantry Division's own historic forces are active.

The division was first activated in December 1917 in World War I, and based at Fort Ord, California for most of its history. Although elements of the division saw brief active service in World War I, it is best known for its participation in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II where it took heavy casualties engaging the Imperial Japanese Army in the Aleutian Islands, Leyte, and Okinawa. Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the division was stationed in Japan and Korea, and with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 was one of the first units in action. It took part in the Inchon Landings and the advance north until Chinese forces counter-attacked and almost overwhelmed the scattered division. The 7th later went on to fight in the Battle of Pork Chop Hill and the Battle of Old Baldy.

After the Korean War ended, the division returned to the United States. In the late 1980s, it briefly saw action overseas in Operation Golden Pheasant in Honduras and Operation Just Cause in Panama. In the early 1990s, it provided domestic support to the civil authorities in Operation Green Sweep and during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. The division's final role was as a training and evaluation unit for Army National Guard brigades, which it undertook until its inactivation in 2006.

On 26 April 2012, the Department of Defense announced the reactivation of the 7th Infantry Division headquarters as an administrative unit.

History

World War I

The 7th Infantry Division was activated on 6 December 1917, exactly eight months after the American entry into World War I, as the 7th Division of the Regular Army at Camp Wheeler, Georgia.[4] One month later, it prepared to deploy to Europe as a part of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).[4] Most of the division sailed to Europe aboard the SS Leviathan.[5]

|

World War I organization

|

While on the Western Front, the 7th Division did not see action at full divisional strength, though its infantry and reconnaissance elements did engage German forces.[5] On 11 October 1918, it first came under shell fire and later, at Saint-Mihiel, came under chemical attack.[5] Elements of the 7th probed up toward Prény near the Moselle River, capturing positions and driving German forces out of the region.[5] It was at this time that the division first received its shoulder sleeve insignia.[7]

In early November, the 7th Division began preparing for an assault on the Hindenburg Line as part of the Second Army.[5] The division launched a reconnaissance in force on the Voëvre plain, but the main assault was never conducted as hostilities ended on 11 November 1918 with the signing of the Armistice with Germany.[5] During its 33 days on the front line, the 7th Division suffered 1,709 casualties,[8] including 204 killed in action and 1,505 wounded in action.[9] and was awarded a campaign streamer for Lorraine.[4] The division then served on occupation duties as it began preparations to return to the United States.[4]

Interwar period

The 7th Division arrived home in late 1919, served at Camp Funston, Kansas, until July 1920, and moved to Camp Meade, Maryland[5] until 22 September 1921, when it was inactivated due to funding cuts.[10]

The 7th Division was represented in the active Regular Army from 1921 to 1939 by its even-numbered infantry brigade (the 14th) and select supporting elements. Other units of the division were placed on the Regular Army Inactive list and staffed by Organized Reserve personnel. These reserve units occasionally trained with the 14th Infantry Brigade at Fort Riley, Fort Crook, Fort Snelling, and Fort Leavenworth, and conducted the Citizens' Military Training Camps in the division's area. The division was formed on a provisional status during maneuvers in the 1920s and 1930s, and the division headquarters was activated for the August 1937 Fourth United States Army maneuvers at Camp Ripley, Minnesota, with the Minnesota Army National Guard's 92nd Infantry Brigade.[11]

World War II

|

World War II organization

|

On 1 July 1940, the 7th Division was formally reactivated at Camp Ord, California,[10] under the command of Major General Joseph W. Stilwell.[4] Most of the early troops in the division were conscripted as a part of the US Army's first peacetime military draft.[5] The 7th Division was assigned to III Corps of the Fourth United States Army,[5] and transferred to Longview, Washington, in August 1941 to participate in tactical maneuvers. Following this training, the division moved back to Fort Ord, California, where it was located when the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor caused the United States to declare war. The formation proceeded almost immediately to San Jose, California, arriving 11 December 1941 to help protect the west coast and allay civilian fears of invasion.[4] The 53rd Infantry Regiment was removed from the 7th Division and replaced with the 159th Infantry Regiment, newly deployed from the California Army National Guard.[4] For the early parts of the war, the division participated mainly in construction and training roles. Subordinate units also practiced boat loading at the Monterey Wharf and amphibious assault techniques at the Salinas River in California.[5]

On 9 April 1942, the division was formally redesignated as the 7th Motorized Division and transferred to Camp San Luis Obispo on 24 April 1942.[10] Three months later, divisional training commenced in the Mojave Desert in preparation for its planned deployment to the African theater.[4] It was again designated the 7th Infantry Division on 1 January 1943, when the motorized equipment was removed from the unit and it became a light infantry division once more,[10] as the Army eliminated the motorized division concept fearing it would be logistically difficult and that the troops were no longer needed in North Africa. The 7th Infantry Division began rigorous amphibious assault training under US Marines from the Fleet Marine Force, before being deployed to fight in the Pacific theater instead of Africa.[4] USMC General Holland Smith oversaw the unit's training.[13]

Aleutian Islands

Elements of the 7th Infantry Division first saw combat in the amphibious assault on Attu Island, the western-most Japanese entrenchment in the Aleutian islands chain of Alaska.[14] Elements landed on 11 May 1943,[15] spearheaded by the 17th Infantry Regiment. The initial landings were unopposed,[16] but Japanese forces mounted a counteroffensive the next day, and the 7th Infantry Division fought an intense battle over the tundra against strong Japanese resistance.[9] The division was hampered by its inexperience and poor weather and terrain conditions, but was eventually able to coordinate an effective attack.[17] The fight for the island culminated in a battle at Chichagof Harbor,[18] when the division destroyed all Japanese resistance on the island[9] on 29 May, after a suicidal Japanese bayonet charge.[19][20] During its first fight of the war, 549 soldiers of the division were killed, while killing 2,351 Japanese and taking 28 prisoners.[19] After American forces secured the island chain, the 159th Infantry Regiment was ordered to stay, and the 184th Infantry Regiment took its place as the 7th Division's third infantry regiment. The 184th Infantry remained with the division until the end of the war. The 159th Infantry Regiment stayed on the island for some time longer until returning to the Lower 48, where it remained until the end of the war.[21]

American forces then began preparing to move against nearby Kiska island, termed Operation Cottage, the final fight in the Aleutian Islands Campaign.[19] In August 1943, elements of the 7th Infantry Division took part in an amphibious assault on Kiska with a brigade from the 6th Canadian Infantry Division, only to find the island deserted by the Japanese.[9] It was later discovered that the Japanese had withdrawn their 5,000-soldier garrison during the night of 28 July, under cover of fog.[19]

Marshall Islands

After the campaign, the division moved to Hawaii where it trained in new amphibious assault techniques on the island of Maui, before returning to Schofield Barracks on Oahu for brief leave. It was reassigned to V Amphibious Corps, a US Marine Corps command.[21] The division left Pearl Harbor on 22 January 1944, for an offensive on Japanese territory.[5] On 30 January 1944, the division landed on islands in the Kwajalein Atoll in conjunction with the 4th Marine Division, code named Operation Flintlock.[22] The 7th Division landed on the namesake island while the 4th Marine Division forces struck the outlying islands of Roi and Namur.[23] The division made landfall on the western beaches of the island at 09:30 on 1 February.[24] It advanced halfway through the island by nightfall the next day, and reached the eastern shore at 1335 hours on 4 February, having wrested the island from the Japanese.[24] The victory put V Amphibious Corps in control of all 47 islands in the atoll. The 7th Infantry Division suffered 176 killed and 767 wounded. On 7 February, the division departed the atoll and returned to Schofield Barracks.[25]

Elements took part in the capture of Engebi in the Eniwetok Atoll on 18 February 1944, code named Operation Catchpole. Because of the speed and success of the attack on Kwajalein, the attack was undertaken several months ahead of schedule.[22] After a week of fighting, the division secured the islands of the atoll.[26] The division then returned to Hawaii to continue training. There, in June 1944, General Douglas MacArthur and President Franklin Roosevelt personally reviewed the division.[25]

Leyte

The 7th Infantry Division left Hawaii on 11 October, heading for Leyte[27] and include the Filipino troops of the Philippine Commonwealth Army and Philippine Constabulary were aided against the Japanese.[clarification needed] At this time it was under the command of XXIV Corps of the Sixth United States Army.[28][29] On 20 October 1944, the division made an assault landing at Dulag, Leyte,[30] initially only encountering light resistance.[31] Following a defeat at sea on 26 October, the Japanese launched a large, uncoordinated counteroffensive on the Sixth Army.[32] After heavy fighting, the 184th Infantry secured airstrips at Dulag, while the 17th Infantry secured San Pablo, and the 32nd Infantry took Buri.[26] The 17th Infantry troops moved north to take Dagami on 29 October, in intense jungle warfare that produced high casualties.[26] The division then shifted to the west coast of Leyte on 25 November and attacked north toward Ormoc, securing Valencia on 25 December.[26] An amphibious landing by the 77th Infantry Division effected the capture of Ormoc on 31 December 1944.[26] The 7th Infantry Division joined in the occupation of the city, and engaged the 26th Japanese Infantry Division, which had been holding up the advance of the 11th Airborne Division. The 7th Division's attack was successful in allowing the 11th Airborne Division to move through,[25] however, Japanese forces proved difficult to drive out of the area.[33] As such, operations to secure Leyte continued until early February 1945.[26] Afterward, the division began training for an invasion of the Ryukyu island chain throughout March 1945.[33] It was relieved from the Sixth Army and the Philippine Commonwealth military, which went on to attack Luzon.[34]

Okinawa

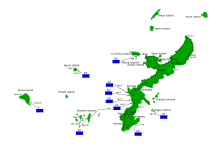

The division was reassigned to XXIV Corps, Tenth United States Army, a newly formed command, and began preparations for the assault on Okinawa.[33][35] The Battle of Okinawa began on 1 April 1945, L-Day, when the 7th Infantry Division participated in an assault landing south of Hagushi, Okinawa alongside the 96th Infantry Division, and the 1st, and 6th Marine Divisions.[36][37] of III Amphibious Corps.[38] These divisions spearheaded an assault that would eventually land 250,000 men ashore.[39] The 7th Division quickly moved to Kadena, taking its airfield, and drove from the west to the east coast of the island on the first day.[40] The division then moved south, encountering stiff resistance from fortifications at Shuri a few days later.[38] The Japanese had moved 90 tanks, much of their artillery, and heavy weapons away from the beaches and into this region.[41] Eventually, XXIV Corps destroyed the defenses after a 51-day battle in the hills of southern Okinawa,[26] which was complicated by harsh weather and terrain.[38] During the operation, the division was bombarded with tens of thousands of rounds of field artillery fire, encountering Japanese armed with spears as it continued its fight across the island.[42] Japanese also fought using irregular warfare techniques, relying on hidden cave systems, snipers, and small-unit ambushes to delay the advancing 7th Infantry Division.[43] After the fight, the division began capturing large numbers of Japanese prisoners for the first time in the war, due to low morale, high casualties, and poor equipment.[44] It fought for five continuous days to secure areas around the Nakagusuku Wan and Skyline Ridge. The division also secured Hill 178 in the fighting.[45] It then moved to Kochi Ridge, securing it after a two-week battle. After 39 days of continuous fighting, the 7th Infantry Division was sent into reserve, having suffered heavy casualties.[46]

After the 96th Infantry Division secured Conical Hill, the 7th Infantry Division returned to the line. It pushed into positions on the southern Ozato Mura hills, where Japanese resistance was heaviest.[47] It was placed on the extreme left flank of the Tenth Army, taking the Ghinen peninsula, Sashiki, and Hanagusuku, fending off a series of Japanese counterattacks.[48] Despite heavy Japanese resistance and prolonged bad weather, the division continued its advance until 21 June 1945, when the battle ended, having seen 82 days of combat.[49] The island and surrendering troops were secured by the next day.[39] During the Battle of Okinawa, the soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division killed between 25,000 and 28,000 Japanese soldiers and took 4,584 prisoners.[5] Balanced against this, the 7th Division suffered 2,340 killed and 6,872 wounded for a total of 9,212 battle casualties[8][n 1] during 208 days of combat.[9] The division was slated to participate in Operation Downfall as a part of XXIV Corps under the First United States Army, but these plans were scrapped after the Japanese surrendered following the use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[50]

|

World War II casualties |

During World War II, soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division were awarded three Medals of Honor, 26 Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal, 982 Silver Star Medals, 33 Legion of Merit Medals, 50 Soldier's Medals, 3,853 Bronze Star Medals, and 178 Air Medals.[9] The division received four campaign streamers and a Philippine Presidential Unit Citation during the war.[9] The three Medals of Honor were awarded to Leonard C. Brostrom, John F. Thorson,[52] and Joe P. Martinez.[8]

Occupation of Japan

A few days after V-J Day, the division moved to Korea to accept the surrender of the Japanese Army in South Korea.[26] After the war, the division served as an occupation force in Korea and Japan. Seven thousand, five hundred members of the unit returned to the United States, and the 184th Infantry Regiment was reassigned to the California Army National Guard, cutting the division to half its combat strength. To replace it, the 31st Infantry Regiment was assigned to the division.[53] The 7th Infantry Division remained on occupation duty in Korea patrolling the 38th parallel until 1948, when it was reassigned to occupation duty in Japan, in charge of northern Honshū and all of Hokkaido.[54] During this time, the US Army underwent a drastic reduction in size. At the end of World War II, it contained 89 divisions, but by 1950, the 7th Infantry Division was one of only 10 active divisions in the force.[55] It was one of four understrength divisions on occupation duty in Japan alongside the 1st Cavalry Division, 24th Infantry Division, and 25th Infantry Division, all under control of the Eighth United States Army.[56][57]

Korean War

At the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the 7th Infantry Division commander, Major General David G. Barr, assembled the division at Camp Fuji near Mount Fuji.[58] The division was already depleted due to post-war shortages of men and equipment[56] and further depleted as it sent large numbers of reinforcements to strengthen the 25th Infantry Division and 1st Cavalry Division, which were sent into combat in South Korea in July.[59] The division was reduced to 9,000 men, half of its wartime strength.[60] To replenish the ranks of the understrength division, the Republic of Korea Army (ROK) assigned over 8,600 Korean soldiers to the division.[61] The Colombian Battalion was at times attached to the division. With the addition of priority reinforcements from the US, the division strengthwas eventually increased to 25,000 when it entered combat.[62] Also fighting with the 7th Infantry Division for much of the war were members of the three successive Kagnew Battalions sent by Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia as part of the UN forces.[63]

The division paired with the 1st Marine Division under US X Corps to participate in the Inchon Landing,[61] code named Operation Chromite.[64] The two divisions would be supported by the US 3rd Infantry Division in reserve.[64] Supported by 230 ships of the US Navy,[65] X Corps began landing at Inchon on 15 September 1950, catching the Korean People's Army (KPA) by surprise.[66] The 7th Infantry Division began landing on 18 September,[67] after the 1st Marine Division, securing its right flank.[68] X Corps quickly advanced to Seoul and the 1st Marine Division attacked the 20,000 defenders of the city from the north and southwest,[69] while the 7th Infantry Division's 32nd Infantry Regiment attacked from the southeast.[70] The 31st Infantry followed behind.[71][72] Seoul fell to X Corps after suffering moderate casualties, particularly for the Marines.[73] The division then began advancing south to cut off KPA supply routes.[74][75] The 32nd Infantry crossed the Han River on 25 September to create a bridgehead,[76][77] and the next day, the division advanced to Osan 30 miles (48 km) south of Seoul[78] and linked up with the 1st Cavalry Division of Eighth United States Army which had broken out from the Pusan perimeter starting on 16 September and then began a general offensive northward against crumbling KPA opposition.[70] Radio miscommunication and attack from nearby KPA forces caused a miscommunication, the soldiers of the 1st Cavalry and 7th Infantry briefly engaged in a small-arms firefight with one another, unable to communicate.[79] Seoul was liberated one day later with the help of air assets from the 1st Cavalry Division.[80] The combined forces of the Eighth Army cut off and captured retreating KPA forces.[81] X Corps was kept separate from the rest of the Eighth Army to avoid placing a burden on the logistical system.[82] As part of the UN offensive into North Korea 7th Division withdrew to Pusan to conduct another amphibious assault on the east coast of North Korea.[83] The entire battle for Inchon and Seoul cost the division 106 killed, 411 wounded and 57 missing American soldiers, and 43 killed, 102 wounded South Korean soldiers.[84] The Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) entered the war on the side of North Korea, making their first attacks in late October.

The 7th Infantry Division began landing at Wonsan on 26 October,[85][86] and Iwon on 29 October.[83] The landing was delayed due to the presence of mines, and by the time X Corps came ashore, ROK forces moving overland had already occupied the ports.[87] The division advanced to Hyesanjin, on the China–North Korea border by the Yalu River, one of the northernmost advances for UN soldiers of the war. Much of X Corps followed behind.[83] On 21 November, the 17th Infantry reached the banks of the Yalu River.[88][89] The advance went quickly for the 7th Infantry Division and ROK troops while the Marines were not able to advance as quickly.[90] The division halted its advance until 24 November while other units of the Eighth Army's IX Corps and ROK II Corps caught up and supply lines were established.[91] During this time, the 7th Division's regiments were spread out on the front line. The 31st Infantry Regiment remained at the Chosin Reservoir with the 1st Marine Division while the 32nd and 17th Infantry Regiments were much further to the northeast, closer to ROK I Corps.[92] It was during this time that the division was served by a new type of unit, the 1st Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (M.A.S.H.).[93]

Chinese intervention

The UN forces renewed their offensive on 24 November before being stopped by the PVA Second Phase Offensive starting on 25 November with attacks on Eighth Army's IX Corps and ROK II Corps in the west and X Corps in the east.[91] X Corps found itself under attack from the PVA 20th, 26th and 27th Field Armies, commanding a total of 12 divisions.[94] During the furious action that followed, the 7th Infantry Division's spread out regiments were unable to resist the overwhelming PVA forces.[95] Three of the division's infantry battalions were attacked from all sides the next day.[96] 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry (nicknamed Task Force Faith) was trapped with two other battalions[97] by the PVA 80th and 81st Divisions from the 27th Field Army. In the subsequent Battle of Chosin Reservoir, the three battalions were destroyed by overwhelming PVA forces[94] suffering over 2,000 casualties.[98] The 31st Infantry suffered heavy casualties trying to fight back the PVA forces further north, but the 17th Infantry was spared of heavy attack,[99] retreating along the Korean coastline, out of range of the offensive.[100] By the time X Corps ordered a retreat, most of the 7th Infantry Division, save the 17th Infantry Regiment, had suffered 40 percent casualties.[101] The scattered elements of the division saw repeated attacks as they attempted to withdrawal to the port of Hungnam in December 1950.[102] These attacks cost the division another 100 killed before it was evacuated on 21 December.[103] The division suffered 2,657 killed and 354 wounded during the retreat. Most of the dead were members of Task Force Faith.[88]

The division returned to the front lines in early 1951, spearheaded by the 17th Infantry, which had suffered the fewest casualties from the PVA offensive. Division elements advanced through Tangyang in South Korea, and blocking PVA offensives from the northwest.[104] The division reached full strength and saw action around Cheehon, Chungju, and Pyeongchang as part of an effort to push the KPA and PVA forces back above the 38th Parallel and away from Seoul.[105] The 7th Infantry Division engaged in a series of successful "limited objective" attacks in the early weeks of February, a series of small unit attacks and ambushes between the two sides.[106] It would continue slowly advancing and clearing enemy hilltop positions through April.[107] By April the entire Eighth Army was advancing north as one line stretching across the peninsula, reaching the 38th Parallel by May.[108] The division, now assigned to IX Corps, then assaulted and fought a fierce three-day battle culminating with the recapture of the terrain that had been lost near the Hwachon Reservoir just over the 38th Parallel in North Korea. In capturing the town bordering on the reservoir it cut off thousands of PVA/KPA troops.[109] The division fought on the front lines until June 1951 when it was assigned to the reserve for a brief rest and refitting.[5]

Stalemate

When the division returned to the lines in October, after another assignment in reserve, it moved to the Heartbreak Ridge sector recently vacated by the 2nd Infantry Division, where it was supported by the 3rd Infantry Division and 1st Cavalry Division. During this new deployment the division fought in the Battle for Heartbreak Ridge, to take an area of staging grounds for the PVA/KPA armies.[110] It remained static in the region until 23 February 1952 when it was sent into reserve and relieved by the 25th Infantry Division.[111] The next year saw the 7th Division engaged in an extended campaign for nearby land, the Battle of Old Baldy.[112] The 7th Division continued to defend "Line Missouri" through September 1952, though it became known as the "Static Line" as UN forces made few meaningful gains in the time.[113]

The 7th Infantry Division's Operation Showdown launched in the early morning hours of 14 October 1952, with the 31st Infantry and 32nd Infantry at the head of the attack. The target of the assault was the Triangle Hill complex northeast of Kumhwa.[114] The 7th Infantry Division remained in the Triangle Hill area until the end of October, when it was relieved by the 25th Infantry Division. The 7th Infantry Division was highly praised by commanders for its tenacity through the fight.[112]

The division continued patrol activity around Old Baldy and Pork Chop Hill into 1953, digging tunnels and building a network of outposts and bunkers on and around the hill.[115] In April, the KPA began stepping up offensive operations against UN forces. During the Battle of Porkchop Hill, the PVA 67th and 141st Divisions overran Pork Chop Hill using massed infantry and artillery fire.[116] The hill had been under the control of the 31st Infantry.[117] The 31st counterattacked with reinforcements from the 17th Infantry and recaptured the area the next day. On 6 July the PVA/KPA launched a determined attack against Pork Chop resulting in five days of fierce fighting with few meaningful results.[118] By the end of July, five infantry battalions from the 31st and 17th were defending the hill, while a PVA division was in position to attack it.[119] During this standoff, the UN ordered the 7th Infantry Division to retreat from the hill in preparation for an armistice, which would end major hostilities.[120]

During the Korean War, the division saw a total of 850 days of combat, suffering 15,126 casualties, including 3,905 killed in action and 10,858 wounded.[121][n 2] For the next few years, the division remained on defensive duty along the 38th parallel, under the command of the Eighth Army.[121] Thirteen members of the division received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the Korean War: Charles H. Barker,[122] Raymond Harvey,[123] Einar H. Ingman, Jr.,[124] William F. Lyell,[125] Joseph C. Rodriguez,[126] Richard Thomas Shea, Daniel D. Schoonover,[127] Jack G. Hanson,[128] Ralph E. Pomeroy,[129] Edward R. Schowalter, Jr.,[130] Benjamin F. Wilson,[131] Don C. Faith, Jr.,[132] and Anthony T. Kahoʻohanohano.[133]

Cold War

From 1953 to 1971, the 7th Infantry Division defended the Korean Demilitarized Zone. Its main garrison was Camp Casey, South Korea.[121] On 1 July 1963, the division was reorganized as a Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD). Three Brigade Headquarters were activated and Infantry units were reorganized into battalions. The division's former headquarters company grew into the 1st Brigade, 7th Infantry Division while the 13th Infantry Brigade was reactivated as the 2nd Brigade, 7th Infantry Division.[6] The 14th Infantry Brigade was reactivated as the 3rd Brigade, 7th Infantry Division[134] In 1965 the division received its distinctive unit insignia, which alluded to its history during the Korean War.[7]

In October 1974 the 7th reactivated at its former garrison, Fort Ord.[135] The unit did not see any action in Vietnam or during the post-war era, but was tasked to keep a close watch on South American developments. It trained at Fort Ord, Camp Roberts, Fort Hunter Liggett and Fort Irwin. On 1 October 1985 the division was redesignated as the 7th Infantry Division (Light), organized again as a light infantry division.[135] It was the first US division specially designed as such. The various battalions of the 31st, and 32nd regiments moved from the division, replaced by battalions from other regiments, including battalions from the 21st Infantry Regiment, the 27th Infantry Regiment, and the 9th Infantry Regiment. The 27th and 9th infantry regiments participated in Operation Golden Pheasant in Honduras.[135]

In 1989 the 7th Infantry Division participated in Operation Just Cause in Panama, briefly occupying the country in conjunction with the 82nd Airborne Division. Elements of the 7th Infantry Division landed in the northern areas of Colón Province, Panama, securing the Coco Solo Naval Station, Fort Espinar, France Field, and Colón while the 82nd Airborne and US Marines fought in the more heavily populated southern region. Once Panama City was under US control, the 82nd quickly re-deployed and left the city under the control of the 7th Division's 9th Infantry Regiment until after the capture of Manuel Noriega.[135] It suffered four killed and three wounded in the operation.[8]

In 1991 the Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended the closing of Fort Ord due to the escalating cost of living on the central California coastline. By 1994, Fort Ord closed and the 7th Infantry Division subsequently relocated to Fort Lewis, Washington.[135] Elements of the division including the 2nd Brigade participated in one final mission in the United States before inactivation; quelling the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, called Operation Garden Plot.[136] The division's soldiers patrolled the streets of Los Angeles to act as crowd control and supported the Los Angeles Police Department and California National Guard in preventing the riots from escalating in violence.[137] It was part of a force of 13,000 troops called into the city.[138]

In 1993 the division was slated to be inactivated as part of the post-Cold War drawdown of the US Army. The 1st Brigade relocated to Fort Lewis in 1993 and was reflagged on 15 August 1995 as the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division; while the 2nd Brigade and the 3rd Brigade of the 7th was inactivated at Fort Ord. The division headquarters was formally inactivated on 16 June 1994 at Fort Lewis.[135]

|

1988 organization[139]

|

National Guard training command and Fort Carson

At the end of the Cold War, the US Army considered new options for the integration and organization of active duty, Army Reserve and Army National Guard units in training and deployment. Two division headquarters activated in the active duty component for training National Guard units. The 7th Infantry Division and the 24th Infantry Division headquarters were selected.[140] The subordinate brigades of the divisions did not activate so they could not be deployed as divisions, however their active duty status would allow the headquarters to focus on the national guard units under them full-time.[141]

The headquarters company of the 7th Infantry Division (Light) formally reactivated on 4 June 1999, at Fort Carson, Colorado, as the first Active Component/Reserve Component division.[142] The reserve formations that made up the 7th Infantry Division included the 39th Infantry Brigade Combat Team of the Arkansas National Guard, the 41st Infantry Brigade Combat Team of the Oregon National Guard and the 45th Infantry Brigade Combat Team of the Oklahoma National Guard. Fort Carson became the new headquarters for the division.[140]

The division headquarters also provided training assistance in preparation for small-scale National Guard operations, Joint Readiness Training Center rotations, leadership training for National Guard commanders, and annual summer training for the three brigades.[140] As a part of this commitment, the 7th Infantry Division headquarters would deploy a command element to serve as higher headquarters for large-scale training and field exercises, evaluating and coordinating the units as they trained. It would also conduct quarterly status checks with the three brigades to discuss readiness and resource issues affecting those units, ensuring that they were at peak performance should they be needed.[140]

To expand upon the concept of Reserve component and National Guard components, the First Army activated Division East and Division West, two commands responsible for training reserve units' readiness and mobilization exercises. Division West, activated at Fort Carson.[143] This transformation was part of an overall restructuring of the US Army to streamline the organizations overseeing training. The Division West took control of reserve units in 21 states west of the Mississippi River, eliminating the need for the 7th Infantry Division headquarters.[143] As such it was subsequently inactivated for the last time on 22 August 2006 at Fort Carson.[142]

Though it was inactivated, the division was identified as the highest priority inactive division in the United States Army Center of Military History's scheme based on age, campaign participation credit, and unit decorations.[144] All of the division's flags and heraldic items were moved to the National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Georgia following its inactivation.[145] At the time it was determined that, should the US Army decide to activate more divisions in the future, the center would most likely suggest the first new division be the 7th Infantry Division, the second be the 9th Infantry Division, the third be the 24th Infantry Division, the fourth be the 5th Infantry Division, and the fifth be the 2nd Armored Division.[146]

Administrative headquarters reactivation

On 26 April 2012, Secretary of the Army John M. McHugh announced the 7th Infantry Division headquarters would be reactivated at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in October 2012. The headquarters element of about 250 would not activate any subordinate brigades. Instead, it filled an administrative role as a non-deployable unit. In the announcement, McHugh noted the base is home to I Corps, which until then had directly overseen 10 subordinate brigades on the base, while other bases with similar corps headquarters had active division commands for intermediate oversight. The unit oversees the 2nd and 3rd Brigade Combat Teams of the 2nd Infantry Division, as well as the 17th Field Artillery Brigade, 201st Battlefield Surveillance Brigade, 16th Combat Aviation Brigade, and 555th Engineer Brigade, about 21,000 personnel. The mission of the headquarters primarily focuses on making sure soldiers are properly trained and equipped, and that order and discipline is maintained in its subordinate brigades.[147]

In the announcement, McHugh denied that the move was made in response to several high-profile misconduct allegations leveled against soldiers from the base in the Afghanistan War such as the Maywand District murders and the Kandahar massacre.[147] Major General Stephen R. Lanza, the Army's chief of public affairs, was tapped to lead the division.[148] It activated on the base on 10 October 2012.[149]

Current structure

7th Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

7th Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team (1st SBCT), 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team (1st SBCT), 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) 1st Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition

1st Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 5th Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

5th Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 1st Battalion, 37th Field Artillery Regiment (1-37th FAR)

1st Battalion, 37th Field Artillery Regiment (1-37th FAR) 23rd Brigade Engineer Battalion (23rd BEB)

23rd Brigade Engineer Battalion (23rd BEB) 296th Brigade Support Battalion (296th BSB)

296th Brigade Support Battalion (296th BSB)

2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team (2nd SBCT), 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team (2nd SBCT), 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) 8th Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition

8th Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 2nd Battalion, 17th Field Artillery Regiment (2-17th FAR)

2nd Battalion, 17th Field Artillery Regiment (2-17th FAR) 14th Brigade Engineer Battalion (14th BEB)

14th Brigade Engineer Battalion (14th BEB) 2nd Brigade Support Battalion (2nd BSB)

2nd Brigade Support Battalion (2nd BSB)

81st Stryker Brigade Combat Team (81st SBCT)[150]

81st Stryker Brigade Combat Team (81st SBCT)[150]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) 1st Squadron, 82nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition

1st Squadron, 82nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition 1st Battalion, 161st Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

1st Battalion, 161st Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 3rd Battalion, 161st Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

3rd Battalion, 161st Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 1st Battalion, 185th Infantry Regiment (Stryker)

1st Battalion, 185th Infantry Regiment (Stryker) 2nd Battalion, 146th Field Artillery Regiment (2-146th FAR)

2nd Battalion, 146th Field Artillery Regiment (2-146th FAR) 898th Brigade Engineer Battalion (898th BEB)

898th Brigade Engineer Battalion (898th BEB) 181st Brigade Support Battalion (181st BSB)

181st Brigade Support Battalion (181st BSB)

Division Artillery, 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

Division Artillery, 2nd Infantry Division based at Fort Lewis, Washington

16th Combat Aviation Brigade (16th CAB)

16th Combat Aviation Brigade (16th CAB)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)4th Squadron (Heavy-Attack Reconnaissance), 6th Cavalry Regiment, AH-64E Apache and RQ-7 Shadow

1st Battalion (Attack), 229th Aviation Regiment, AH-64E Apache

1st Battalion (Attack), 229th Aviation Regiment, AH-64E Apache 2nd Battalion (Assault), 158th Aviation Regiment, UH-60 Black Hawk

2nd Battalion (Assault), 158th Aviation Regiment, UH-60 Black Hawk 1st Battalion (General Support), 52nd Aviation Regiment, UH-60, CH-47 Chinook and UH-60A+ (MEDEVAC) (supporting US Army Alaska)

1st Battalion (General Support), 52nd Aviation Regiment, UH-60, CH-47 Chinook and UH-60A+ (MEDEVAC) (supporting US Army Alaska) 46th Aviation Support Battalion (46th ASB)

46th Aviation Support Battalion (46th ASB)

17th Field Artillery Brigade (17th FAB)

17th Field Artillery Brigade (17th FAB)

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery (HHB)

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery (HHB) 5th Battalion (HIMARS) High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment (5-3rd FAR)

5th Battalion (HIMARS) High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment (5-3rd FAR) 1st Battalion (HIMARS) High Mobility Arttillery Rocket System, 94th Field Artillery Regiment (1-94th FAR)

1st Battalion (HIMARS) High Mobility Arttillery Rocket System, 94th Field Artillery Regiment (1-94th FAR) Battery F (Target Acquisition), 26th Field Artillery Regiment (F-26th FAR)

Battery F (Target Acquisition), 26th Field Artillery Regiment (F-26th FAR) 308th Brigade Support Battalion (308th BSB)

308th Brigade Support Battalion (308th BSB) 256th Signal Company

256th Signal Company

555th Engineer Brigade

555th Engineer Brigade

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) 864th Engineer Battalion

864th Engineer Battalion 3rd Ordnance Battalion (EOD), operational control: 71st Ordnance Group (EOD)

3rd Ordnance Battalion (EOD), operational control: 71st Ordnance Group (EOD) 110th Chemical Battalion, operational control: 48th Chemical Brigade

110th Chemical Battalion, operational control: 48th Chemical Brigade

201st Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade (201st EMIB)

201st Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade (201st EMIB)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) 502nd Military Intelligence Battalion (502nd MIB)

502nd Military Intelligence Battalion (502nd MIB) 109th Military Intelligence Battalion (109th MIB)

109th Military Intelligence Battalion (109th MIB) 63rd Signal Company (Network Support) (inactivated)

63rd Signal Company (Network Support) (inactivated) 602nd Forward Support Company (inactivated) (602nd FSC)

602nd Forward Support Company (inactivated) (602nd FSC)

Honors

The 7th Infantry Division was awarded one campaign streamer in World War I, four campaign streamers and two unit decorations in World War II, and ten campaign streamers and two unit decorations in the Korean War, for a total of fifteen campaign streamers and four unit decorations in its operational history.[151]

Unit decorations

| Ribbon | Award | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philippine Presidential Unit Citation | 1944–1945 | for service in the Philippines during World War II | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1950 | for the Inchon Landings | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1950–1953 | for service in Korea | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1945–1948; 1953–1971 | for service in Korea |

Campaign streamers

| Conflict | Streamer | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| World War I | Lorraine | 1918 |

| World War II | Aleutian Islands | 1943 |

| World War II | Eastern Mandates | 1944 |

| World War II | Leyte | 1945 |

| World War II | Ryukyus | 1945 |

| Korean War | UN Defensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | UN Offensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Intervention | 1950 |

| Korean War | First UN Counteroffensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Spring Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | UN Summer-Fall Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | Second Korean Winter | 1951–1952 |

| Korean War | Korea, Summer-Fall 1952 | 1952 |

| Korean War | Third Korean Winter | 1952–1953 |

| Korean War | Korea, Summer 1953 | 1953 |

References

Notes

- ^ A 1959 US Army publication gave these numbers as 1,116 killed, and around 6,000 wounded, to make total casualties for World War II 8,135. (Young 1959, p. 524)

- ^ A 1997 division history from Turner Publishing Company gave this figure as 3,927 killed, 10,858 wounded for a total of 14,785 casualties in the Korean War. (Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 77)

Citations

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 6

- ^ "7th Infantry Division". US Army. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "7th Infantry Division Homepage: History". 7th Infantry Division. 2003. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b McGrath 2004, p. 188

- ^ a b "The Institute of Heraldry: 7th Infantry Division". The Institute of Heraldry. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 77

- ^ a b c d e f g Young 1959, p. 524

- ^ a b c d Wilson 1999, p. 217

- ^ Clay, Steven E. (2010). U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919-1941. Combat Studies Institute Press.

- ^ a b Young 1959, p. 592

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 112

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 11

- ^ Horner 2003, p. 41

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 12

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, pp. 13–16

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Horner 2003, p. 42

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 19

- ^ a b Marston 2005, p. 169

- ^ Pimlott 1995, p. 170

- ^ a b Pimlott 1995, p. 171

- ^ a b c Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 25

- ^ a b c d e f g h Young 1959, p. 525

- ^ "7th Infantry Division Homepage: Chronological History". 7th Infantry Division. 2003. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 26

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 26

- ^ Horner 2003, p. 56

- ^ Horner 2003, p. 57

- ^ Horner 2003, p. 59

- ^ a b c Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 31

- ^ Horner 2003, p. 60

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 25

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 188

- ^ Willmott 2004, p. 190

- ^ a b c Pimlott 1995, p. 208

- ^ a b Horner 2003, p. 64

- ^ Pimlott 1995, p. 209

- ^ Marston 2005, p. 215

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 133

- ^ Marston 2005, p. 217

- ^ Willmott 2004, p. 192

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 76

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 38

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 105

- ^ Appleman 2011, p. 110

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 42

- ^ Allen, Thomas B.; Polmar, Norman (1995), Code-Name Downfall, New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 54, ISBN 0-684-80406-9

- ^ a b c d e Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths in World War II, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 60

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 67

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 52

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 211

- ^ a b Stewart 2005, p. 222

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 41

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 44

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 225

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 169

- ^ a b Stewart 2005, p. 227

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 170

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 134

- ^ a b Catchpole 2001, p. 39

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 173

- ^ Malkasian 2001, p. 25

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 206

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 172

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 214

- ^ a b Malkasian 2001, p. 27

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 46

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 212

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 215

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 9

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 210

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 49

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 213

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 223

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 224

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 228

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 249

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 229

- ^ a b c Stewart 2005, p. 230

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 52

- ^ Malkasian 2001, p. 29

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 68

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 10

- ^ a b Varhola 2000, p. 12

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 309

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 307

- ^ a b Stewart 2005, p. 231

- ^ Malkasian 2001, p. 31

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 162

- ^ a b Catchpole 2001, p. 86

- ^ Malkasian 2001, p. 34

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 313

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 328

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 366

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 232

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 320

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 90

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 92

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 367

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 18

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 19

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 382

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 114

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 421

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 239

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 146

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 166

- ^ a b Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 74

- ^ Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 75

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 27

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 302

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 30

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 300

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 240

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 306

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 307

- ^ a b c Varhola 2000, p. 96

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 172

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 88

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 84

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 115

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 168

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 177

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 105

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 155

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 156

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 181

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 56

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients — Korean War". United States Army. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McGrath 2004, p. 189

- ^ a b c d e f Gardener & Stahura 1997, p. 54

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 105

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 109

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 110

- ^ Gordon L. Rottmen, Inside the US Army Today, Osprey Publishing 1988

- ^ a b c d "GlobalSecurity.org: 7th Infantry Division". GlobalSecurity. 2003. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Report to the Secretary of Defense (2000)". United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Lineage and Honors Information: 7th Infantry Division". United States Army Center of Military History. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "First Army Organization". First United States Army Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ McKenney 1997, pp. 3, 22

- ^ McKenney 1997, p. 22

- ^ McKenney 1997, pp. 3, 22

- ^ a b Petrich, Marisa (26 April 2012). "SecArmy announces new division headquarters coming to Lewis-McChord". Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington: JBLM Public Affairs Office. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Misterek, Matt (11 May 2012). "General who will lead new HQ at JBLM has public-affairs practice". Tacoma, Washington: The News Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kibler, Lindsey (12 October 2012). "7th ID eyes Pacific, reactivates as Army's 'Stryker Division'". Joint Base Lewis–McChord: U.S. Army Public Affairs. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Wilson 1999, p. 218

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War we Lost, New York City, New York: Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (2011), Okinawa: The Last Battle, New York City, New York: Skyhorse Publishing, ISBN 978-1-61608-177-5

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, London, United Kingdom: Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Gardener, Bruce; Stahura, Barbara (1997), Seventh Infantry Division: 1917 1992 World War I, World War Ii, Korea and Panamanian Invasion, Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-56311-398-7

- Glenn, Russell W. (2000), The City's Many Faces: Glenneding of the Arroyo Center—Marine Corps Warfighting Lab-J8 Urban Working Group Conference on Joint Urban Operations, Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, ISBN 978-0-8330-2814-3

- Horner, David (2003), The Second World War, Vol. 1: The Pacific, Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-0-415-96845-4

- Malkasian, Carter (2001), The Korean War, Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-282-1

- Marston, Daniel (2005), The Pacific War Companion: from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima, Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-882-3

- McGrath, John J. (2004), The Brigade: A History: Its Organization and Employment in the US Army, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-4404-4915-4

- McKenney, Janice (1997), Reflagging the Army, Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, OCLC 37875549

- Pimlott, John (1995), The Historical Atlas of World War II, New York City, New York: Henry Holt and Company, ISBN 978-0-8050-3929-0

- Stewart, Richard W. (2005), American Military History Volume II: The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917–2003, Army Historical Series, Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, ISBN 978-0-16-072541-8

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

- Willmott, H.P. (2004), The Second World War in the Far East, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, ISBN 978-1-58834-192-1

- Wilson, John B. (1999), Armies, Corps, Divisions, And Separate Brigades, Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center for Military History, ISBN 0-16-049992-5

- Young, Gordon Russell (1959), Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States, Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, ISBN 978-0-7581-3548-3

Further reading

External links

- 7th Infantry Division Home Page

- Lineage at the United States Army Center of Military History

- The short film Big Picture: The 7th Infantry Division is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Use dmy dates from January 2013

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army

- Military units and formations established in 1917

- United States Army divisions of World War I

- United States Army units and formations in the Korean War

- United States Army divisions during World War II

- Military units and formations disestablished in 2006

- Aleutian Islands Campaign

- Military units of the United States Army in South Korea

- Military units and formations of the United States in the Cold War