Apollo

In Greek and Roman mythology, Apollo (Ancient Greek Template:Polytonic, Apóllōn; or Ἀπέλλων, Apellōn), the ideal of the kouros, was the archer-god of medicine and healing, light, truth, archery and also a bringer of death-dealing plague; as the leader of the Muses (Apollon Musagetes) and director of their choir, he is a god of music and poetry. Hymns sung to Apollo were called Paeans.

As the patron of Delphi ("Pythian Apollo") Apollo is an oracular god; in Classical times he took the place of Helios as god of the sun. Apollo was also considered to have dominion over colonists, over medicine, mediated through his son Asclepius, and was the patron defender of herds and flocks.

Apollo is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of the chaste huntress Artemis, who took the place of Selene as goddess of the moon. As the prophetic deity of the Delphic oracle, Apollo was one of the most important and many-sided of the Olympian deities. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu. In Roman mythology he is known as Apollo and increasingly, especially during the third century BC, as Apollo Helios he became identified with Sol, the Sun.[1]

Cult sites

Unusual among the Olympic deities, Apollo had two cult sites that had widespread influence: Delos and Delphi. In cult practice, Delian Apollo and Pythian Apollo (the Apollo of Delphi) were so distinct that they might both have shrines in the same locality.[2] Theophoric names such as Apollodorus or Apollonios and cities named Apollonia are met with throughout the Greek world. Apollo's cult was already fully established when written sources commence, ca 700 BCE.

Oracular shrines

Apollo had a famous oracle in Delphi, and other notable ones in Clarus and Branchidae. His oracular shrine in Abea in Phocis, was important enough to be consulted by Croesus (Herodotus, 1.46). Looking at the ancient oracular shrines to Apollo from the oldest to the youngest we find:

- In Didyma, an oracle on the coast of Anatolia, south west of Lydian (Luwian) Sardis, in which priests from the lineage of the Branchidae received inspiration by drinking from a healing spring located in the temple.

- In Hieropolis, Asia Minor, priests breathed in vapors that for small animals were highly poisonous. Small animals and birds were cast into the Plutonium, named after Pluto—the god of death and the underworld—as a demonstration of their power. Prophecy was by movements of an archaic aniconic wooden xoanon of Apollo.

- In Delos, there was an oracle to the Delian Apollo, during summer. The Heiron (Sanctuary) of Apollo adjacent to the Sacred Lake, was the place where the god was born.

- In Corinth, the Oracle of Corinth came from the town of Tenea, from prisoners supposedly taken in the Trojan War

- In Bassae in the Peloponnese

- In Abae, near Delphi

- In Delphi, the Pythia became filled with the pneuma of Apollo, said to come from a spring inside the Adyton. Apollo took this temple from Gaia.

- At Patara, in Lycia, there was a seasonal winter oracle of Apollo, said to have been the place where the god went from Delos. As at Delphi the oracle at Patara was a woman.

- At Clarus, on the west coast of Asia Minor; as at Delphi a holy spring which gave off a pneuma, from which the priests drank.

- In Segesta in Sicily, the latest of the series, another oracle of Apollo was seized originally from Gaia.

Oracles were also given by sons of Apollo.

- In Oropus, north of Athens, the oracle Amphiaraus, was said to be the son of Apollo; Oropus also had a sacred spring.

- in Labadea, 20 miles east of Delphi, Trophonius, another son of Apollo, killed his brother and fled to the cave where he was also afterwards consulted as an oracle.

- Apollo is also a very prominant figure in many Greek novels and plays as a plague dealing god.

Festivals

The chief Apollonian festivals were the Carneia, Carpiae, Daphnephoria, Delia, Hyacinthia, Pyanepsia, Pythia and Thargelia.

Attributes and symbols

Apollo's most common attributes were the lyre and the bow. Other attributes of his included the kithara (an advanced version of the common lyre) and plectrum. Another common emblem was the sacrificial tripod, representing his prophetic powers. The Pythian Games were held in Apollo's honor every four years at Delphi. The laurel bay plant was used in expiatory sacrifices and in making the crown of victory at these games. The palm was also sacred to Apollo because he had been born under one in Delos. Animals sacred to Apollo included wolves, dolphins and roe, swans and grasshoppers (symbolizing music and song), hawks, ravens, crows and snakes (referencing Apollo's function as the god of prophecy), mice, laurel and griffins, mythical eagle-lion hybrids of Eastern origin.

As god of colonization, Apollo gave oracular guidance on colonies, especially during the height of colonization, 750–550 BC. According to Greek tradition, he helped Cretan or Arcadian colonists found the city of Troy. However, this story may reflect a cultural influence which had the reverse direction: Hittite cuneiform texts mention a Minor Asian god called Appaliunas or Apalunas in connection with the city of Wilusa, which is now regarded as being identical with the Greek Illios by most scholars. In this interpretation, Apollo’s title of Lykegenes can simply be read as "born in Lycia", which effectively severs the god's supposed link with wolves (possibly a folk etymology).

In literary contexts Apollo represents harmony, order, and reasons—characteristics contrasted with those of Dionysus, god of wine, who represents ecstasy and disorder. The contrast between the roles of these gods is reflected in the adjectives Apollonian and Dionysian. However, the Greeks thought of the two qualities as complementary: the two gods are brothers, and when Apollo at winter left for Hyperborea, he would leave the Delphi Oracle to Dionysus. This contrast appears to be shown on the two sides of the Borghese Vase.

Roman Apollo

The Roman worship of Apollo was adopted from the Greeks. Roman name of Apollo was Phoebus. There is a tradition that the Delphic oracle was consulted as early as the period of the kings of Rome during the reign of Tarquinius Superbus. In 430 BCE, a temple was dedicated to Apollo on the occasion of a pestilence. During the Second Punic War in 212 BCE, the Ludi Apollinares ("Apollonian Games") were instituted in his honor. In the time of Augustus, who considered himself under the special protection of Apollo and was even said to be his son, his worship developed and he became one of the chief gods of Rome. After the battle of Actium, Augustus enlarged his old temple, dedicated a portion of the spoils to him, and instituted quinquennial games in his honour. He also erected a new temple on the Palatine hill and transferred the secular games, for which Horace composed his Carmen Saeculare, to Apollo and Diana.

Origins of the cult of Apollo

It appears that both Greek and Etruscan Apollos came to the Aegean during the Archaic Period (from 1,100 BCE till 800 BCE) from Anatolia. Homer pictures him on the side of the Trojans, not the Achaeans, in the Trojan War and he has close affiliations with Luwian Apaliuna, who in turn seems to have traveled west from further east. Late Bronze Age (from 1,700 BCE - 1,200 BCE) Hittite and Hurrian "Aplu"[citation needed], like Homeric Apollo, was a God of the Plague, and resembles the mouse god Apollo Smintheus. Here we have an apotropaic situation, where a god originally bringing the plague was invoked to end illness, merging over time through fusion with the Mycenaean "doctor" god Paieon (PA-JA-WO in Linear B); Paean, in Homer, was the Greek physician of the gods. In other writers the word is a mere epithet of Apollo in his capacity as a god of healing, but it is now known from Linear B that Paean was originally a separate deity.

Homer left the question unanswered, whilst Hesiod separated the two, and in later poetry Paean was invoked independently as a god of healing. It is equally difficult to separate Paean or Paeon in the sense of "healer" from Paean in the sense of "song." It was believed to refer to the ancient association between the healing craft and the singing of spells, but here we see a shift from the concerns to the original sense of "healer" gradually giving way to that of "hymn," from the phrase Ιή Παιάν.[citation needed]

Such songs were originally addressed to Apollo, and afterwards to other gods, Dionysus, Helios, Asclepius, gods associated with Apollo. About the fourth century BC the paean became merely a formula of adulation; its object was either to implore protection against disease and misfortune, or to offer thanks after such protection had been rendered. It was in this way that Apollo became recognised as the God of Music. Apollo's role as the slayer of the Python led to his association with battle and victory; hence it became the Roman custom for a paean to be sung by an army on the march and before entering into battle, when a fleet left the harbour, and also after a victory had been won.

Hurrian Aplu itself seems to be derived from the Babylonian "Aplu" meaning a "son of"—a title that was given to the Babylonian plague god, Nergal (son of Enlil). Apollo's links with oracles again seem to be associated with wishing to know the outcome of an illness.

Apollo killed the Python of Delphi and took over that oracle, so he is vanquisher of unconscious terrors.[citation needed] He is golden-haired like the sun; he is an archer who shoots arrows of insight [citation needed] and/or death; he is a god of music and the lyre. Healing belongs to his realm: he was the father of Asclepius, the god of medicine. The Muses are part of his retinue, so that music, history, dreams,[citation needed] poetry, dance, all belong to him. The Muses are those we call on when we evoke creative imagination to give us helpful images…

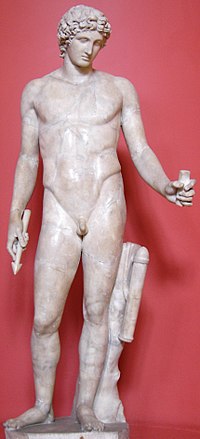

Apollo in art

In art, Apollo is depicted as a handsome beardless young man, often with a lyre or bow in hand. In the late second century floor mosaic from El Djem, Roman Thysdrus, (illustration, right), he is identifiable as Apollo Helios by his effulgent halo, though now even a god's divine nakedness is concealed by his cloak, a mark of increasing conventions of modesty in the later Empire. Another haloed Apollo in mosaic, from Hadrumentum, is in the museum at Sousse [1]. The conventions of this representation, head tilted, lips slightly parted, large-eyed, curling hair cut in locks grazing the neck, were developed in the 3rd century BCE to depict Alexander the Great (Bieber 1964, Yalouris 1980). Some time after this mosaic was executed, the earliest depictions of Christ will be beardless and haloed.

Mythology

Birth

When Hera discovered that Leto was pregnant and that Zeus was the father, she banned Leto from giving birth on "terra-firma", or the mainland, or any island at sea. In her wanderings, Leto found the newly created floating island of Delos, which was neither mainland nor a real island, and she gave birth there. The island was surrounded by swans. Afterwards, Zeus secured Delos to the bottom of the ocean. This island later became sacred to Apollo.

It is also stated that Hera kidnapped Ilithyia, the goddess of childbirth, to prevent Leto from going into labor. The other gods tricked Hera into letting her go by offering her a necklace, nine yards long, of amber. Mythographers agree that Artemis was born first and then assisted with the birth of Apollo, or that Artemis was born one day before Apollo, on the island of Ortygia and that she helped Leto cross the sea to Delos the next day to give birth to Apollo. Apollo was born on the seventh day (ἡβδομαγενης) of the month Thargelion —according to Delian tradition— or of the month Bysios— according to Delphian tradition. The seventh and twentieth, the days of the new and full moon, were ever afterwards held sacred to him.

Youth

In his youth, Apollo killed the chthonic dragon Python, which lived in Delphi beside the Castalian Spring because Python had attempted to rape Leto while she was pregnant with Apollo and Artemis. This was the spring which emitted vapors that caused the oracle at Delphi to give her prophesies. Apollo killed Python but had to be punished for it, since Python was a child of Gaia.

Apollo has his ominous aspects, too. Marsyas, who dared challenge him to a music contest, was flayed after he lost. Apollo brought down arrows of plague upon the Greeks because they dishonored his priest Chryses. Apollo's arrows of plague struck Niobe, who, excessively proud of her seven sons and seven daughters, had disparaged Apollo's mother, Leto, for having only two children (Apollo and Artemis).

Apollo and Admetus

When Zeus struck down Apollo's son, Asclepius, with a lightning bolt for resurrecting the dead (transgressing Themis by stealing Hades's subjects), Apollo in revenge killed the Cyclops, who had fashioned the bolt for Zeus. Apollo would have been banished to Tartarus forever, but was instead sentenced to one year of hard labor as punishment, thanks to the intercession of his mother, Leto. During this time he served as shepherd for King Admetus of Pherae in Thessaly. Admetus treated Apollo well, and, in return, the god conferred great benefits on Admetus.

Apollo helped Admetus win Alcestis, the daughter of King Pelias and later convinced the Fates to let Admetus live past his time, if another took his place. But when it came time for Admetus to die, his elderly parents, whom he had assumed would gladly die for him, refused to cooperate. Instead, Alcestis took his place, but Heracles managed to "persuade" Thanatos, the god of death, to return her to the world of the living.

Apollo during the Trojan War

Apollo shot arrows infected with the plague into the Greek encampment during the Trojan War in retribution for Agamemnon's insult to Chryses, a priest of Apollo whose daughter Chryseis had been captured. He demanded her return, and the Achaeans complied, indirectly causing the anger of Achilles, which is the theme of the Iliad.

When Diomedes injured Aeneas, (Iliad), Apollo rescued him. First, Aphrodite tried to rescue Aeneas but Diomedes injured her as well. Aeneas was then enveloped in a cloud by Apollo, who took him to Pergamos, a sacred spot in Troy.

Apollo aided Paris in the killing of Achilles by guiding the arrow of his bow into Achilles' heel. One interpretation of his motive is that it was in revenge for Achilles' sacrilege in murdering Troilus, the god's own son by Hecuba, on the very altar of the god's own temple.

Niobe

A queen of Thebes and wife of Amphion, Niobe boasted of her superiority to Leto because she had fourteen children (Niobids), seven male and seven female, while Leto had only two. Apollo killed her sons as they practiced athletics, with the last begging for his life, and Artemis her daughters. Apollo and Artemis used poisoned arrows to kill them, though according to some versions of the myth, a number of the Niobids were spared (Chloris, usually). Amphion, at the sight of his dead sons, either killed himself or was killed by Apollo after swearing revenge. A devastated Niobe fled to Mt. Siplyon in Asia Minor and turned into stone as she wept. Her tears formed the river Achelous. Zeus had turned all the people of Thebes to stone and so no one buried the Niobids until the ninth day after their death, when the gods themselves entombed them.

Apollo's consorts and children

Female lovers

Apollo chased the nymph Daphne, daughter of Peneus, who had scorned him. His infatuation was caused by an arrow from Eros, who was jealous because Apollo had made fun of his archery skills. Eros also claimed to be irritated by Apollo's singing. Simultaneously, however, Eros had shot a hate arrow into Daphne, causing her to be repulsed by Apollo. Following a spirited chase by Apollo, Daphne prayed to Mother Earth, or, alternatively, her father - a river god - to help her and he changed her into a Laurel tree, which became sacred to Apollo: see Apollo and Daphne.

Apollo had an affair with a human princess named Leucothea, daughter of Orchamus and sister of Clytia. Leucothea loved Apollo who disguised himself as Leucothea's mother to gain entrance to her chambers. Clytia, jealous of her sister because she wanted Apollo for herself, told Orchamus the truth, betraying her sister's trust and confidence in her. Enraged, Orchamus ordered Leucothea to be buried alive. Apollo refused to forgive Clytia for betraying his beloved, and a grieving Clytia wilted and slowly died. Apollo changed her into an incense plant, either heliotrope or sunflower, which follows the sun every day.

Marpessa was kidnapped by Idas but was loved by Apollo as well. Zeus made her choose between them, and she chose Idas on the grounds that Apollo, being immortal, would tire of her when she grew old.

Castalia was a nymph whom Apollo loved. She fled from him and dived into the spring at Delphi, at the base of Mt. Parnassos, which was then named after her. Water from this spring was sacred; it was used to clean the Delphian temples and inspire poets.

By Cyrene, Apollo had a son named Aristaeus, who became the patron god of cattle, fruit trees, hunting, husbandry and bee-keeping. He was also a culture-hero and taught humanity dairy skills and the use of nets and traps in hunting, as well as how to cultivate olives.

With Hecuba, wife of King Priam of Troy, Apollo had a son named Troilius. An oracle prophesied that Troy would not be defeated as long as Troilius reached the age of twenty alive. He and his sister, Polyxena were ambushed and killed by Achilles.

Apollo also fell in love with Cassandra, daughter of Hecuba and Priam, and Troilius' half-sister. He promised Cassandra the gift of prophecy to seduce her, but she rejected him afterwards. Enraged, Apollo indeed gifted her with the ability to know the future, with a curse that no one would ever believe her.

Coronis, daughter of Phlegyas, King of the Lapiths, was another of Apollo's liaisons. Pregnant with Asclepius, Coronis fell in love with Ischys, son of Elatus. A crow informed Apollo of the affair. When first informed he disbelieved the crow and turned all crows black (where they were previously white) as a punishment for spreading untruths. When he found out the truth he sent his sister, Artemis, to kill Coronis. As a result he also made the crow sacred and gave them the task of announcing important deaths. Apollo rescued the baby and gave it to the centaur Chiron to raise. Phlegyas was irate after the death of his daughter and burned the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Apollo then killed him for what he did.

In Euripides' play Ion, Apollo fathered Ion by Creusa, wife of Xuthus. Creusa left Ion to die in the wild, but Apollo asked Hermes to save the child and bring him to the oracle at Delphi, where he was raised by a priestess.

Male lovers

Jacopo Caraglio; 16th c. Italian engraving

Apollo, the eternal beardless kouros himself, had the most prominent male relationships of all the Greek Gods. That was to be expected from a god who was god of the palaestra, the athletic gathering place for youth who all competed in the nude, a god said to represent the ideal educator and therefore the ideal erastes, or lover of a boy (Sergent, p.102). All his lovers were younger than him, in the style of the Greek pederastic relationships of the time. Many of Apollo's young beloveds died "accidentally", a reflection on the function of these myths as part of rites of passage, in which the youth died in order to be reborn as an adult.

Hyacinth was one of his male lovers. Hyacinthus was a Spartan prince, beautiful and athletic. The pair were practicing throwing the discus when Hyacinthus was struck in the head by a discus blown off course by Zephyrus, who was jealous of Apollo and loved Hyacinthus as well. When Hyacinthus died, Apollo is said in some accounts to have been so filled with grief that he cursed his own immortality, wishing to join his lover in mortal death. Out of the blood of his slain lover Apollo created the hyacinth flower as a memorial to his death, and his tears stained the flower petals with άί άί, meaning alas. The Festival of Hyacinthus was a celebration of Sparta.

One of his other liaisons was with Acantha, the spirit of the acanthus tree. Upon his death, he was transformed into a sun-loving herb by Apollo, and his bereaved sister, Acanthis, was turned into a thistle finch by the other gods.

Another male lover was Cyparissus, a descendant of Heracles. Apollo gave the boy a tame deer as a companion but Cyparissus accidentally killed it with a javelin as it lay asleep in the undergrowth. Cyparissus asked Apollo to let his tears fall forever. Apollo turned the sad boy into a cypress tree, which was said to be a sad tree because the sap forms droplets like tears on the trunk.

Apollo and the birth of Hermes

Hermes was born on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. The story is told in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes. His mother, Maia, had been secretly impregnated by Zeus, in a secret affair. Maia wrapped the infant in blankets but Hermes escaped while she was asleep. Hermes ran to Thessaly, where Apollo was grazing his cattle. The infant Hermes stole a number of his cows and took them to a cave in the woods near Pylos, covering their tracks. In the cave, he found a tortoise and killed it, then removed the insides. He used one of the cow's intestines and the tortoise shell and made the first lyre. Apollo complained to Maia that her son had stolen his cattle, but Hermes had already replaced himself in the blankets she had wrapped him in, so Maia refused to believe Apollo's claim. Zeus intervened and, claiming to have seen the events, sided with Apollo. Hermes then began to play music on the lyre he had invented. Apollo, a god of music, fell in love with the instrument and offered to allow exchange of the cattle for the lyre. Hence, Apollo became a master of the lyre and Hermes invented a kind of pipes-instrument called a syrinx.

Later, Apollo exchanged a caduceus for a syrinx from Hermes.

Other stories

Apollo gave the order, through the Oracle at Delphi, for Orestes to kill his mother, Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus. Orestes was punished fiercely by the Erinyes (female personifications of vengeance) for this crime.

In the Odyssey, Odysseus and his surviving crew landed on an island sacred to Helios the sun god, where he kept sacred cattle. Though Odysseus warned his men not to (as Tiresias and Circe had told him), they killed and ate some of the cattle and Helios had Zeus destroy the ship and all the men save Odysseus.

Apollo also had a lyre-playing contest with Cinyras, his son, who committed suicide when he lost.

Apollo killed the Aloadae when they attempted to storm Mt. Olympus.

It was also said that Apollo rode on the back of a swan to the land of the Hyperboreans during the winter months, a swan that he also lent to his beloved Hyacinthus to ride.

Apollo turned Cephissus into a sea monster.

Musical contests

Pan

Once Pan had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo, and to challenge Apollo, the god of the lyre, to a trial of skill. Tmolus, the mountain-god, was chosen to umpire. Pan blew on his pipes, and with his rustic melody gave great satisfaction to himself and his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and all but Midas agreed with the judgment. He dissented, and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer, and caused them to become the ears of a donkey.

Marsyas

Marsyas was a satyr who challenged Apollo to a contest of music. He had found an aulos on the ground, tossed away after being invented by Athena because it made her cheeks puffy. Marsyas lost and was flayed alive in a cave near Calaenae in Phrygia for his hubris to challenge a god. His blood turned into the river Marsyas.

Another variation is that Apollo played his instrument (the lyre) upside down. Marsyas could not do this with his instrument (the flute), and so Apollo hung him from a tree and flayed him alive. [taken from MAN MYTH & MAGIC by Richard Cavendish]

Epithets and cult titles

Apollo, like other Greek deities, had a number of epithets applied to him, reflecting the variety of roles, duties, and aspects ascribed to the god. However, while Apollo has a great number of appellations in Greek myth, only a few occur in Latin literature, chief among them Phoebus ("shining one"), which was very commonly used by both the Greeks and Romans in Apollo's role as the god of light.

In Apollo's role as healer, his appellations included Akesios and Iatros, meaning "healer". He was also called Alexikakos ("restrainer of evil") and Apotropaeus ("he who averts evil"), and was referred to by the Romans as Averruncus ("averter of evils"). As a plague god and defender against rats and locusts, Apollo was known as Smintheus ("mouse-catcher") and Parnopius ("grasshopper"). The Romans also called Apollo Culicarius ("driving away midges"). In his healing aspect, the Romans referred to Apollo as Medicus ("the Physician"), and a temple was dedicated to Apollo Medicus at Rome, probably next to the temple of Bellona.

As a god of archery, Apollo was known as Aphetoros ("god of the bow") and Argurotoxos ("with the silver bow"). The Romans referred to Apollo as Articenens ("carrying the bow") as well. As a pastoral shepherd-god, Apollo was known as Nomios ("wandering").

Apollo was also known as Archegetes ("director of the foundation"), who oversaw colonies. He was known as Klarios, from the Doric klaros ("allotment of land"), for his supervision over cities and colonies.

He was known as Delphinios ("Delphinian"), meaning "of the womb", in his association with Delphoi (Delphi). At Delphi, he was also known as Pythios ("Pythian"). An aitiology in the Homeric hymns connects the epitheton to dolphins. Kynthios, another common epithet, stemmed from his birth on Mt. Cynthus. He was also known as Lyceios or Lykegenes, which either meant "wolfish" or "of Lycia", Lycia being the place where some postulate that his cult originated.

Specifically as god of prophecy, Apollo was known as Loxias ("the obscure"). He was also known as Coelispex ("he who watches the heavens") to the Romans. Apollo was attributed the epithet Musagetes as the leader of the muses, and Nymphegetes as "nymph-leader".

Acesius was a surname of Apollo, under which he was worshipped in Elis, where he had a temple in the agora. This surname, which has the same meaning as akestor and alezikakos, characterized the god as the averter of evil.[3]

Etymology

The name Apollo might have been derived from a Pre-Hellenic compound Apo-ollon,[citation needed] likely related to an archaic verb Apo-ell- and literally meaning "he who elbows off", and thus "the Dispelling One". Indeed, he seems to have personified the power to dispel and ward off evil, which was related to his association with the darkness-dispelling power of the morning sun and the conceived power of reason and prophecy to dispel doubt and ignorance. In addition, Apollo's dispelling aspect made him associated with:

- city walls and doorways, which served as bulwarks to guard against trespassers;

- disembarkations and expatriations to colonies, which served to carry people away;

- like his son Asclepius, healing, which dispelled disease and illness;

- shepherds tending their flocks, who warded off pests and predators;

- music and the arts, which dispelled discord and barbarism;

- fit and skilled young men, with their highly important ability to dispel intruders and invading armies;

- the ability of foresight into the future.

An explanation given by Plutarch in Moralia is that Apollon signified unity, since pollon meant "many", and the prefix a- was a negative. Thus, Apollon could be read as meaning "deprived of multitude". Apollo was consequently associated with the monad.

Hesychius connects the name Apollo with the Doric απελλα, which means assembly, so that Apollo would be the god of political life, and he also gives the explanation σηκος ("fold"), in which case Apollo would be the god of flocks and herds.

Spoken-word myths - audio files

| Apollo Myths as told by story tellers |

|---|

| 1. Apollo and Hyacinthus, read by Timothy Carter |

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer, Illiad ii.595 - 600 (c. 700 BC); Various 5th century BC vase paintings; Palaephatus, On Unbelievable Tales 46. Hyacinthus (330 BC); Apollodorus, Library 1.3.3 (140 BC); Ovid, Metamorphoses 10. 162-219 (AD 1 - 8); Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.1.3, 3.19.4 (AD 160 - 176); Philostratus the Elder, Images i.24 Hyacinthus (AD 170 - 245); Philostratus the Younger, Images 14. Hyacinthus (AD 170 - 245); Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods 14 (AD 170); First Vatican Mythographer, 197. Thamyris et Musae |

In popular culture

- In the 1960s, NASA named its Apollo Lunar program after Apollo, because he was considered the god of all wisdom. Many people mistakenly believe that the rockets that carried astronauts to the Moon were called Apollo rockets; they were actually Saturn V rockets, on top of which sat the Apollo spacecraft.

- Apollo is the subject of Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem of 1820 the "Hymn of Apollo"

- William Rimmer's artistic depiction of Apollo was used as the symbol of the band Led Zeppelin's record label Swan Song Records.

- Apollo is the name of a Daedalus class battlecruiser in the science-fiction television series Stargate Atlantis.

- Apollo is the name of a superhuman (inspired by Superman) with connections to the sun, in the superhero comic The Authority.

- In both series of Battlestar Galatica one of the central protagonists, Captain Lee Adama, is often referred to by his call sign Apollo.

References

Pre-World War I

- D. Bassi, Saggio di Bibliografia mitologica, i. Apollo (1896)

- Gaston Colin, Le Culte d'Apollon pythien à Athènes (1905)

- Daremberg and Saglio Dictionnaire des antiquités

- Louis Dyer, Studies of the Gods in Greece (1891)

- L. Farnell, Cults of the Greek States, iv. (1907)

- O. Gruppe, Griechische Mythologie und Religionsgeschichte, ii. (1906)

- R. Hecker, De Apollinis apud Romanos Cultu (Leipzig, 1879)

- J. Marquardt, Römische Staalsverwaltung, iii.

- Arthur Milchhoefer, Über den attischen Apollon (Munich, 1873)

- Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft: II, "Apollon". The best repertory of cult sites (Burkert).

- L. Preller, Griechische und romische Mythologie (4th ed. by C. Robert)

- W. H. Roscher, Studien zur vergleichenden Mythologie der Griechen und Romer, i. (Leipzig, 1873)

- W. H. Roscher, Lexikon der Mythologie

- F. L. W. Schwartz, De antiquissima Apollinis Natura (Berlin, 1843)

- J. A. Schönborn, Über das Wesen Apollons (Berlin, 1854)

- Theodor Schreiber, Apollon Pythoktonos (Leipzig, 1879)

- William Smith (lexicographer), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, article on Apollo, [2]

- G. Wissowa, Religion und Kultus der Romer (1902)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Modern

- M. Bieber, 1964. Alexander the Great in Greek and Roman Art (Chicago)

- N. Yalouris, 1980. The Search for Alexander (Boston) Exhibition.

- Walter Burkert, 1985. Greek Religion (Harvard University Press) III.2.5 passim

- Karl Kerenyi, Apollon: Studien über Antiken Religion und Humanität rev. ed. 1953.

- Karl Kerenyi , 1951 The Gods of the Greeks

- Robert Graves, 1960. The Greek Myths, revised edition (Penguin)

Rapper GhostfaceKillah of the Wu-tang clan often refers to himself under the moniker 'Sun god', and the song titled "Apollo Kids" was a lead single in his sophomore album Supreme Clientele.

Notes

- ^ In Hellenistic times, Apollo became conflated with Helios, god of the sun, and his sister similarly equated with Selene, goddess of the moon. However, Apollo and Helios remained separate beings in literary and mythological texts. For the iconography of the Alexander-Helios type, see H. Hoffmann, 1963. "Helios," in Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 2, pp. 117-23; cf. Yalouris, no. 42.

- ^ Burkert, p. 143.

- ^ "Acesius". Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London, 1880.

External links

- Greek Mythology resource

- The Temple of Apollo, Rome

- The stories of Apollo and Hyacinthus; and Apollo and Cyparissus; and Apollo and Orpheus

- Apollo and the Romans

Further reading

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1953. Apollon: Studien über Antike Religion und Humanität, second edtion

- Pfeiff, K.A., 1943. Apollon: Wandlung seines Bildes in der griechischen Kunst. Traces the changing iconography of Apollo.