International Mathematical Olympiad

The International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) is an annual six-problem mathematical olympiad for pre-college students, and is the oldest of the International Science Olympiads.[1] The first IMO was held in Romania in 1959. It has since been held annually, except in 1980. More than 100 countries, representing over 90% of the world's population, send teams of up to six students,[2] plus one team leader, one deputy leader, and observers.[3]

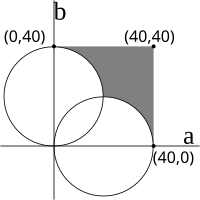

The content ranges from extremely difficult algebra and pre-calculus problems to problems on branches of mathematics not conventionally covered at school and often not at university level either, such as projective and complex geometry, functional equations, combinatorics, and well-grounded number theory, of which extensive knowledge of theorems is required. Calculus, though allowed in solutions, is never required, as there is a principle that anyone with a basic understanding of mathematics should understand the problems, even if the solutions require a great deal more knowledge. Supporters of this principle claim that this allows more universality and creates an incentive to find elegant, deceptively simple-looking problems which nevertheless require a certain level of ingenuity.

The selection process differs by country, but it often consists of a series of tests which admit fewer students at each progressing test. Awards are given to approximately the top-scoring 50% of the individual contestants. Teams are not officially recognized—all scores are given only to individual contestants, but team scoring is unofficially compared more than individual scores.[4] Contestants must be under the age of 20 and must not be registered at any tertiary institution. Subject to these conditions, an individual may participate any number of times in the IMO.[5]

The International Mathematical Olympiad is one of the most prestigious mathematical competitions in the world. In January 2011, Google sponsored €1 million to the International Mathematical Olympiad organization.[6]

History

The first IMO was held in Romania in 1959. Since then it has been held every year except in 1980. That year, it was cancelled due to internal strife in Mongolia.[7] It was initially founded for eastern European member countries of the Warsaw Pact, under the USSR bloc of influence, but later other countries participated as well.[2] Because of this eastern origin, the IMOs were first hosted only in eastern European countries, and gradually spread to other nations.[8]

Sources differ about the cities hosting some of the early IMOs. This may be partly because leaders are generally housed well away from the students, and partly because after the competition the students did not always stay based in one city for the rest of the IMO.[clarification needed] The exact dates cited may also differ, because of leaders arriving before the students, and at more recent IMOs the IMO Advisory Board arriving before the leaders.[9]

Several students, such as Zhuo Qun Song, Teodor von Burg, Lisa Sauermann, John Lian, Josh Li and Christian Reiher, have performed exceptionally well in the IMO, winning multiple gold medals. Others, such as Grigory Margulis, Jean-Christophe Yoccoz, Laurent Lafforgue, Stanislav Smirnov, Terence Tao, Sucharit Sarkar, Grigori Perelman, Ngô Bảo Châu and Maryam Mirzakhani have gone on to become notable mathematicians. Several former participants have won awards such as the Fields Medal.[10]

Scoring and format

The examination consists of six problems. Each problem is worth seven points, so the maximum total score is 42 points. No calculators are allowed. The examination is held over two consecutive days; each day the contestants have four-and-a-half hours to solve three problems. The problems chosen are from various areas of secondary school mathematics, broadly classifiable as geometry, number theory, algebra, and combinatorics. They require no knowledge of higher mathematics such as calculus and analysis, and solutions are often short and elementary. However, they are usually disguised so as to make the solutions difficult. Prominently featured are algebraic inequalities, complex numbers, and construction-oriented geometrical problems, though in recent years the latter has not been as popular as before.[11]

Each participating country, other than the host country, may submit suggested problems to a Problem Selection Committee provided by the host country, which reduces the submitted problems to a shortlist. The team leaders arrive at the IMO a few days in advance of the contestants and form the IMO Jury which is responsible for all the formal decisions relating to the contest, starting with selecting the six problems from the shortlist. The Jury aims to order the problems so that the order in increasing difficulty is Q1, Q4, Q2, Q5, Q3 and Q6. As the leaders know the problems in advance of the contestants, they are kept strictly separated and observed.[12]

Each country's marks are agreed between that country's leader and deputy leader and coordinators provided by the host country (the leader of the team whose country submitted the problem in the case of the marks of the host country), subject to the decisions of the chief coordinator and ultimately a jury if any disputes cannot be resolved.[13]

Selection process

The selection process for the IMO varies greatly by country. In some countries, especially those in East Asia, the selection process involves several tests of a difficulty comparable to the IMO itself.[14] The Chinese contestants go through a camp.[15] In others, such as the United States, possible participants go through a series of easier standalone competitions that gradually increase in difficulty. In the United States, the tests include the American Mathematics Competitions, the American Invitational Mathematics Examination, and the United States of America Mathematical Olympiad, each of which is a competition in its own right. For high scorers in the final competition for the team selection, there also is a summer camp, like that of China.[16]

In countries of the former Soviet Union and other eastern European countries, a team has in the past been chosen several years beforehand, and they are given special training specifically for the event. However, such methods have been discontinued in some countries.[17] In Ukraine, for instance, selection tests consist of four olympiads comparable to the IMO by difficulty and schedule[clarification needed]. While identifying the winners, only the results of the current selection olympiads are considered.[clarification needed]

Awards

The participants are ranked based on their individual scores. Medals are awarded to the highest ranked participants; slightly fewer than half of them receive a medal. The cutoffs (minimum scores required to receive a gold, silver or bronze medal respectively) are then chosen so that the numbers of gold, silver and bronze medals awarded are approximately in the ratios 1:2:3. Participants who do not win a medal but who score seven points on at least one problem receive an honorable mention.[18]

Special prizes may be awarded for solutions of outstanding elegance or involving good generalisations of a problem. This last happened in 1995 (Nikolay Nikolov, Bulgaria) and 2005 (Iurie Boreico), but was more frequent up to the early 1980s.[19] The special prize in 2005 was awarded to Iurie Boreico, a student from Moldova, who came up with a brilliant solution to question 3, which was an inequality involving three variables.

The rule that at most half the contestants win a medal is sometimes broken if it would cause the total number of medals to deviate too much from half the number of contestants. This last happened in 2010 (when the choice was to give either 226 (43.71%) or 266 (51.45%) of the 517 contestants (excluding the 6 from North Korea — see below) a medal),[20] 2012 (when the choice was to give either 226 (41.24%) or 277 (50.55%) of the 548 contestants a medal), and 2013, when the choice was to give either 249 (47.16%) or 278 (52.65%) of the 528 contestants a medal. In these cases, slightly more than half the contestants were awarded a medal.

Penalties

North Korea was disqualified for cheating at the 32nd IMO in 1991 and again at the 51st IMO in 2010.[21] It is the only country to have been accused of cheating.

Summary

| Venue | Year | Date | Top-ranked country[22] | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1959 | July 23 – July 31 | [23] | ||

| 2 | 1960 | July 18 – July 25 | [23] | ||

| 3 | 1961 | July 6 – July 16 | [23] | ||

| 4 | 1962 | July 7 – July 15 | [23] | ||

| 5 | 1963 | July 5 – July 13 | [23] | ||

| 6 | 1964 | June 30 – July 10 | [23] | ||

| 7 | 1965 | July 13 – July 13 | [23] | ||

| 8 | 1966 | July 3 – July 13 | [23] | ||

| 9 | 1967 | July 7 – July 13 | [23] | ||

| 10 | 1968 | July 5 – July 18 | [23] | ||

| 11 | 1969 | July 5 – July 20 | [23] | ||

| 12 | 1970 | July 8 – July 22 | [23] | ||

| 13 | 1971 | July 10 – July 21 | [23] | ||

| 14 | 1972 | July 5 – July 17 | [23] | ||

| 15 | 1973 | July 5 – July 16 | [23] | ||

| 16 | 1974 | July 4 – July 17 | [23] | ||

| 17 | 1975 | July 3 – July 16 | [23] | ||

| 18 | 1976 | July 2 – July 21 | [23] | ||

| 19 | 1977 | July 1 – July 13 | [23] | ||

| 20 | 1978 | July 3 – July 10 | [23] | ||

| 21 | 1979 | June 30 – July 9 | [23] | ||

| The 1980 IMO was due to be held in Mongolia. It was cancelled, and split into two unofficial events in Europe.[24] | |||||

| 22 | 1981 | July 8 – July 20 | [23] | ||

| 23 | 1982 | July 5 – July 14 | [23] | ||

| 24 | 1983 | July 3 – July 12 | [23] | ||

| 25 | 1984 | June 29 – July 10 | [23] | ||

| 26 | 1985 | June 29 – July 11 | [23] | ||

| 27 | 1986 | July 4 – July 15 | [23] | ||

| 28 | 1987 | July 5 – July 16 | [23] | ||

| 29 | 1988 | July 9 – July 21 | [23] | ||

| 30 | 1989 | July 13 – July 24 | [23] | ||

| 31 | 1990 | July 8 – July 19 | [23] | ||

| 32 | 1991 | July 12 – July 23 | [23] | ||

| 33 | 1992 | July 10 – July 21 | [23] | ||

| 34 | 1993 | July 13 – July 24 | [23] | ||

| 35 | 1994 | July 8 – July 20 | [23] | ||

| 36 | 1995 | July 13 – July 25 | [25] | ||

| 37 | 1996 | July 5 – July 17 | [26] | ||

| 38 | 1997 | July 18 – July 31 | [27] | ||

| 39 | 1998 | July 10 – July 21 | [28] | ||

| 40 | 1999 | July 10 – July 22 | [29] | ||

| 41 | 2000 | July 13 – July 25 | [30] | ||

| 42 | 2001 | July 1 – July 14 | [31] | ||

| 43 | 2002 | July 19 – July 30 | [32] | ||

| 44 | 2003 | July 7 – July 19 | [33] | ||

| 45 | 2004 | July 6 – July 18 | [34] | ||

| 46 | 2005 | July 8 – July 19 | [35] | ||

| 47 | 2006 | July 6 – July 18 | [36] | ||

| 48 | 2007 | July 19 – July 31 | [37] | ||

| 49 | 2008 | July 10 – July 22 | [38] | ||

| 50 | 2009 | July 10 – July 22 | [39] | ||

| 51 | 2010 | July 2 – July 14 | [40] | ||

| 52 | 2011 | July 13 – July 24 | [41] | ||

| 53 | 2012 | July 4 – July 16 | [42] | ||

| 54 | 2013 | July 18 – July 28 | [43] | ||

| 55 | 2014 | July 3 – July 13 | [44] | ||

| 56 | 2015 | July 4 – July 16 | [45] | ||

| 57 | 2016 | July 6 – July 16 | [46] | ||

| 58 | 2017 | July 12 – July 23 | [47] | ||

| 59 | 2018 | July 3 – July 14 | [48] | ||

| 60 | 2019 | July 11 – July 22 | [49] | ||

| 61 | 2020 | [50][51] | |||

| 62 | 2021 | [52] | |||

| 63 | 2022 | July 6 – July 16 | [53][54] | ||

Notable achievements

The following nations have achieved the highest team score in the respective competition:

- China, 19 times (from the first participation in 1985 until 2014): in every year from 1989 to 2014 except 1991, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2003, 2007, 2012;

- Soviet Union, 14 times: in 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1979, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1991;

- United States, 7 times: in 1977, 1981, 1986, 1994, 2015, 2016, 2018;

- Hungary, 6 times: in 1961, 1962, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1975;

- Romania, 5 times: in 1959, 1978, 1985, 1987, 1996;

- West Germany, twice: in 1982 and 1983;

- Russia, twice: in 1999 and 2007;

- South Korea, twice: in 2012 and 2017;

- Bulgaria, once: in 2003;[55]

- Iran, once: in 1998;

- East Germany, once: in 1968.

The following nations have achieved an all-members-gold IMO with a full team:

- China, 11 times: in 1992, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2010 and 2011.[56]

- United States, 3 times: in 1994, 2011, and 2016.[57]

- Russia, 2 times: in 2002 and 2008.[58]

- South Korea, twice: in 2012 and 2017.[59]

- Bulgaria, once: in 2003.[60]

The only countries to have their entire team score perfectly in the IMO were the United States in 1994 (they were coached by Paul Zeitz); and Luxembourg, whose 1-member team had a perfect score in 1981. The US's success earned a mention in TIME Magazine.[61] Hungary won IMO 1975 in an unorthodox way when none of the eight team members received a gold medal (five silver, three bronze). Second place team East Germany also did not have a single gold medal winner (four silver, four bronze).

Several individuals have consistently scored highly and/or earned medals on the IMO: As of July 2015 Zhuo Qun Song (Canada) is the most successful participant[62] with five gold medals (including one perfect score in 2015) and one bronze medal.[63] Reid Barton (United States) was the first participant to win a gold medal four times (1998-2001).[64] Barton is also one of only eight four-time Putnam Fellows (2001–04). Christian Reiher (Germany), Lisa Sauermann (Germany), Teodor von Burg (Serbia), and Nipun Pitimanaaree (Thailand) are the only other participants to have won four gold medals (2000–03, 2008–11, 2009–12, 2010–13, and 2011–14 respectively); Reiher also received a bronze medal (1999), Sauermann a silver medal (2007), von Burg a silver medal (2008) and a bronze medal (2007), and Pitimanaaree a silver medal (2009).[65] Wolfgang Burmeister (East Germany), Martin Härterich (West Germany), Iurie Boreico (Moldova), and Lim Jeck (Singapore) are the only other participants besides Reiher, Sauermann, von Burg, and Pitimanaaree to win five medals with at least three of them gold.[2] Ciprian Manolescu (Romania) managed to write a perfect paper (42 points) for gold medal more times than anybody else in the history of the competition, doing it all three times he participated in the IMO (1995, 1996, 1997).[66] Manolescu is also a three-time Putnam Fellow (1997, 1998, 2000).[67] Eugenia Malinnikova (Soviet Union) is the highest-scoring female contestant in IMO history. She has 3 gold medals in IMO 1989 (41 points), IMO 1990 (42) and IMO 1991 (42), missing only 1 point in 1989 to precede Manolescu's achievement.[68]

Terence Tao (Australia) participated in IMO 1986, 1987 and 1988, winning bronze, silver and gold medals respectively. He won a gold medal when he just turned thirteen in IMO 1988, becoming the youngest person at that time[69] to receive a gold medal (a feat matched in 2011 by Zhuo Qun Song of Canada). Tao also holds the distinction of being the youngest medalist with his 1986 bronze medal, alongside 2009 bronze medalist Raúl Chávez Sarmiento (Peru), at the age of 10 and 11 respectively.[70] Representing the United States, Noam Elkies won a gold medal with a perfect paper at the age of 14 in 1981. Note that both Elkies and Tao could have participated in the IMO multiple times following their success, but entered university and therefore became ineligible.

The current ten countries with the best all-time results are as follows:[71]

| Rank | Country | Appearance | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Honorable Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | 147 | 33 | 6 | 0 | |

| 2 | 43 | 119 | 111 | 29 | 1 | |

| 3 | 26 | 92 | 52 | 12 | 0 | |

| 4 | 57 | 81 | 160 | 95 | 10 | |

| 5 | 29 | 77 | 67 | 45 | 0 | |

| 6 | 58 | 75 | 141 | 100 | 4 | |

| 7 | 30 | 70 | 67 | 27 | 7 | |

| 8 | 41 | 59 | 109 | 70 | 1 | |

| 9 | 58 | 53 | 111 | 107 | 10 | |

| 10 | 40 | 49 | 98 | 75 | 11 |

Media coverage

- A documentary, "Hard Problems: The Road To The World's Toughest Math Contest" was made about the United States 2006 IMO team.[72]

- A BBC documentary titled Beautiful Young Minds aired July 2007 about the IMO.

- A BBC fictional film titled X+Y released in September 2014 tells the story of an autistic boy who took part in the Olympiad.

See also

- List of International Mathematical Olympiads

- International Mathematics Competition for University Students (IMC)

- International Science Olympiad

- List of mathematics competitions

- Pan-African Mathematics Olympiads

- Junior Science Talent Search Examination

Notes

Citations

- ^ "International Mathematics Olympiad (IMO)". 2008-02-01.

- ^ a b c "Geoff Smith (August 2017). "UK IMO team leader's report". University of Bath" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ "The International Mathematical Olympiad 2001 Presented by the Akamai Foundation Opens Today in Washington, D.C." Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ Tony Gardiner (1992-07-21). "33rd International Mathematical Olympiad". University of Birmingham. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "The International Mathematical Olympiad" (PDF). AMC. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ Google Europe Blog: Giving young mathematicians the chance to shine. Googlepolicyeurope.blogspot.com (2011-01-21). Retrieved on 2013-10-29.

- ^ Turner, Nura D. A Historical Sketch of Olympiads: U.S.A. and International The College Mathematics Journal, Vol. 16, No. 5 (Nov., 1985), pp. 330-335

- ^ "Singapore International Mathematical Olympiad (SIMO) Home Page". Singapore Mathematical Society. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ "Norwegian Students in International Mathematical Olympiad". Archived from the original on 2006-10-20. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ (Lord 2001)

- ^ (Olson 2004)

- ^ (Djukić 2006)

- ^ "IMO Facts from Wolfram". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ (Liu 1998)

- ^ Chen, Wang. Personal interview. February 19, 2008.

- ^ "The American Mathematics Competitions". Archived from the original on 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ David C. Hunt. "IMO 1997". Australian Mathematical Society. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "How Medals Are Determined". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "IMO '95 regulations". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "51st International Mathematical Olympiad Results". Retrieved 2011-07-25.

- ^ "International Mathematical Olympiad: Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ^ a b "Ranking of countries". International Mathematical Olympiad. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai "Historical Record of US Teams". Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ^ Unofficial events were held in Finland and Luxembourg in 1980. "UK IMO register". IMO register. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- ^ "IMO 1995". Canadian Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-02-29. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 1996". Canadian Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 1997" (in Spanish). Argentina. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "IMO 1998". Republic of China. Archived from the original on 1998-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 1999". Canadian Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 2000". Wolfram. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "IMO 2001". Canadian Mathematical Society. Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Andreescu, Titu (2004). USA & International Mathematical Olympiads 2002. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-815-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "IMO 2003". Japan. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 2004". Greece. Archived from the original on 2004-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 2005". Mexico. Archived from the original on 2005-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "IMO 2006". Slovenia. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "IMO 2007". Vietnam. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "IMO 2008". Spain. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "IMO 2009" (in German). Germany. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "51st IMO 2010". IMO. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "52nd IMO 2011". IMO. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "53rd IMO 2012". IMO. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "54th International Mathematical Olympiad". Universidad Antonio Nariño. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "55th IMO 2014". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "56th IMO 2015". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "57th IMO 2016". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "58th IMO 2017". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "59th IMO 2018". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "60th IMO 2019". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "61st IMO 2020". IMO. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "61st IMO 2020". Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- ^ "62nd IMO 2021". IMO. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ "63rd IMO 2022". IMO. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ "63rd IMO 2020". Department of Mathematics, University of Os. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- ^ "Results of the 44th International Mathematical Olympiad". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "Team Results: China at International Mathematical Olympiad".

- ^ "Team Results: US at International Mathematical Olympiad".

- ^ "Team Results: Russia at International Mathematical Olympiad".

- ^ "Team Results: South Korea at International Mathematical Olympiad".

- ^ "Team Results: Bulgaria at International Mathematical Olympiad".

- ^ "No. 1 and Counting". Time. 1994-08-01. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ "International Mathematical Olympiad Hall of Fame 2015". Imo-official.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ "IMO Official Record for Zhuo Qun (Alex) Song". Imo-official.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ "IMO's Golden Boy Makes Perfection Look Easy". Science. 293: 597. doi:10.1126/science.293.5530.597. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "International Mathematical Olympiad Hall of Fame". Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "IMO team record". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "The Mathematical Association of America's William Lowell Putnam Competition". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ (Vakil 1997)

- ^ "A packed house for a math lecture? Must be Terence Tao". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "Peru won four silver and two bronze medals in International Math Olympiad". Living in Peru. July 22, 2009.

- ^ "Results: Cumulative Results by Country". imo-official.org. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- ^ Hard Problems: The Road to the World's Toughest Math Contest, Zala Films and the Mathematical Association of America, 2008.

References

- Xu, Jiagu (2012). Lecture Notes on Mathematical Olympiad Courses, For Senior Section. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-4368-94-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Xiong, Bin; Lee, Peng Yee (2013). Mathematical Olympiad in China (2009-2010). World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-4390-21-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Xu, Jiagu (2009). Lecture Notes on Mathematical Olympiad Courses, For Junior Section. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-4293-53-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Olson, Steve (2004). Count Down. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-25141-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verhoeff, Tom (August 2002). "The 43rd International Mathematical Olympiad: A Reflective Report on IMO 2002" (PDF). Computing Science Report, Faculty of Mathematics and Computing Science, Eindhoven University of Technology, Vol. 2, No. 11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Djukić, Dušan (2006). The IMO Compendium: A Collection of Problems Suggested for the International Olympiads, 1959-2004. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24299-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lord, Mary (July 23, 2001). "Michael Jordans of math - U.S. Student whizzes stun the cipher world". U.S. News & World Report. 131 (3): 26.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saul, Mark (2003). "Mathematics in a Small Place: Notes on the Mathematics of Romania and Bulgaria" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 50: 561–565.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vakil, Ravi (1997). A Mathematical Mosaic: Patterns & Problem Solving. Brendan Kelly Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-895997-28-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Liu, Andy (1998). Chinese Mathematics Competitions and Olympiads. AMT Publishing. ISBN 1-876420-00-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links