Raksha Bandhan

| Raksha Bandhan | |

|---|---|

A rakhi being tied during Raksha Bandhan | |

| Official name | Raksha Bandhan |

| Also called | Rakhi, Saluno, Ujjwal Silono, Rakri |

| Observed by | Hindus, traditionally |

| Type | Religious, cultural,ujjwal Choudhary secular |

| Date | Purnima (full moon) of Shrawan |

| Related to | Bhai Duj, Bhai Tika, Sama Chakeva |

"Mayer's (1960: 219) observation for central India would not be inaccurate for most communities in the subcontinent:

A man's tie with his sister is accounted very close. The two have grown up together, at an age when there is no distinction made between the sexes. And later, when the sister marries, the brother is seen as her main protector, for when her father has died to whom else can she turn if there is trouble in her conjugal household.

The parental home, and after the parents' death the brother's home, often offers the only possibility of temporary or longer-term support in case of divorce, desertion, and even widowhood, especially for a woman without adult sons. Her dependence on this support is directly related to economic and social vulnerability."[2]

Raksha Bandhan, also Rakshabandhan,[3] is a popular, traditionally Hindu, annual rite, or ceremony, which is central to a festival of the same name, celebrated in India, some other parts of South Asia, and among people around the world influenced by Hindu culture. On this day, sisters of all ages tie a talisman, or amulet, called the rakhi, around the wrists of their brothers, symbolically protecting them, receiving a gift in return, and traditionally investing the brothers with a share of the responsibility of their potential care.[2]

Raksha Bandhan is observed on the last day of the Hindu lunar calendar month of Shraavana, which typically falls in August. The expression "Raksha Bandhan," Sanskrit, literally, "the bond of protection, obligation, or care," is now principally applied to this ritual. Until the mid-20th-century, the expression was more commonly applied to a similar ritual, also held on the same day, with precedence in ancient Hindu texts, in which a domestic priest ties amulets, charms, or threads on the wrists of his patrons, or changes their sacred thread, and receives gifts of money; in some places, this is still the case.[4][5] In contrast, the sister-brother festival, with origins in folk culture, had names which varied with location, with some rendered as Saluno,[6][7] Silono,[8] and Rakri.[4] A ritual associated with Saluno included the sisters placing shoots of barley behind the ears of their brothers.[6]

Of special significance to married women, Raksha Bandhan is rooted in the practice of territorial or village exogamy, in which a bride marries out of her natal village or town, and her parents, by custom, do not visit her in her married home.[9] In rural north India, where village exogamy is strongly prevalent, large numbers of married Hindu women travel back to their parents' homes every year for the ceremony.[10][11] Their brothers, who typically live with the parents or nearby, sometimes travel to their sisters' married home to escort them back. Many younger married women arrive a few weeks earlier at their natal homes and stay until the ceremony.[12] The brothers serve as lifelong intermediaries between their sisters' married and parental homes,[13] as well as potential stewards of their security.

In urban India, where families are increasingly nuclear, the festival has become more symbolic, but continues to be highly popular. The rituals associated with this festival have spread beyond their traditional regions and have been transformed through technology and migration,[14] the movies,[15] social interaction,[16] and promotion by politicized Hinduism,[17][18] as well as by the nation state.[19]

Among women and men who are not blood relatives, there is also a transformed tradition of voluntary kin relations, achieved through the tying of rakhi amulets, which have cut across caste and class lines,[20] and Hindu and Muslim divisions.[21] In some communities or contexts, other figures, such as a matriarch, or a person in authority, can be included in the ceremony in ritual acknowledgement of their benefaction.[22]

Etymology, meaning, and usage

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2008, the Hindi word, rākhī derives from the Sanskrit rakṣikā, a join: rakṣā protection, amulet ( < rakṣ- to protect + -ikā, diminutive suffix.)[23]

- 1829 The first attested use in the English language dates to 1829, in James Tod's, Ann. & Antiq. Rajasthan I. page: 312, "The festival of the bracelet (Rakhi) is in Spring ... The Rajpoot dame bestows with the Rakhi the title of adopted brother; and while its acceptance secures to her all the protection of a ‘cavaliere servente’, scandal itself never suggests any other tie to his devotion."[23]

- 1857, Forbes: Dictionary of Hindustani and English Saluno: the full moon in Sawan at which time the ornament called rakhi is tied around the wrist. [24]

- 1884, Platts: Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi, and English راکهي राखी rākhī (p. 582) H راکهي राखी rākhī [S. रक्षिका], s.f. A piece of thread or silk bound round the wrist on the festival of Salūno or the full moon of Sāvan, either as an amulet and preservative against misfortune, or as a symbol of mutual dependence, or as a mark of respect; the festival on which such a thread is tied;:—rākhī-bandhan, s.f. The festival called rākhī. [25]

- 1899 Monier-Williams: A Sanskrit-English dictionary Rakshā: "a sort of bracelet or amulet,any mysterious token used as a charm, ... a piece of thread or silk bound round the wrist on partic occasions (esp. on the full moon of Śrāvaņa, either as an amulet and preservative against misfortune, or as a symbol of mutual dependence, or as a mark of respect".[26]

- 1990, Jack Goody "The ceremony itself involves the visit of women to their brothers ... on a specific day of the year when they tie a gaudy decoration on the right wrists of their brothers, which is at once a defence against misfortune, a symbol of dependence, and a mark of respect."

- 1965–1975, Hindi Sabd Sagara: राखी १ "राखी १— संज्ञा स्त्री० [सं० रक्षा] वह मंगलसूत्र जो कुछ विशिष्ट अवसरों पर, विशेपतः श्रावणी पूर्णिमा के दिन ब्राह्मण या और लोग अपने यजमानों अथवा आत्मीयों के दाहिने हाथ की कलाई पर बाँधते हैं । (That Mangalsutra (lucky or auspicious thread) which on special occasions, especially the full moon day of the month of Shravani, Brahmins or others tie around the right wrist of their patrons or intimates.) From: Dasa, Syamasundara. Hindi sabdasagara. Navina samskarana. Kasi: Nagari Pracarini Sabha, 1965-1975. 4332 pp.

- 1976, Adarsh Hindi Shabdkosh रक्षा (संज्ञा स्त्रीलिंग): कष्ट, नाश, या आपत्ति से अनिष्ट निवारण के लिए हाथ में बंधा हुआ एक सूत्र; -बंधन (पुलिंग) श्रावण शुक्ला पूर्णिमा को होनेवाला हिंदुओं का एक त्यौहार जिसमे हाथ की कलाई पर एक रक्षा सूत्र बाँधा जाता है. Translation: raksha (masculine noun): A thread worn around the wrist for the prevention of distress, destruction, tribulation, or misfortune; -bandhan (masculine): "a Hindu festival held on the day of the full moon in the month of Shravana in which a raksha thread is tied around the wrist.[27]

- 1993, Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary रक्षा बंधन: m. Hindi, the festival of Rakshabandhan held on the full moon of the month of Savan, when sisters tie a talisman (rakhi q.v.) on the arms of their brothers and receive small gifts of money from them. [28]

- 2000, Samsad Bengali-English Dictionary রাখি rākhi: a piece of thread which one ties round the wrist of another in order to safeguard the latter from all evils. ̃পূর্ণিমা n. the full moon day of the month of Shravan (শ্রাবণ) when a rakhi is tied round the wrist of another. ̃বন্ধন n. act or the festival of tying a rakhi (রাখি) round the wrist of another. [29]

- 2013, Oxford Urdu-English Dictionary راکھے ra:khi: 1. (Hinduism) (i) rakhi, bracelet of red or yellow strings tied by a woman round the wrist of a man on a Hindu festival to set up brotherly relations. بندھن- -bandhan: festival of rakhi. [30]

Traditional regions of observance

Scholars who have written about the ritual, have usually described the traditional region of its observance as north India; however, also included are: central India, western India and Nepal, as well other regions of India, and overseas Hindu communities such as in Fiji. Anthropologist Jack Goody, whose field study was conducted in Nandol, in Gujarat, describes Rakshabandhan as an "annual ceremony ... of northern and western India."[31] Anthropologist Michael Jackson, writes, "While traditional North Indian families do not have a Father's or Mother's Day, or even the equivalent of Valentine's Day, there is a Sister's Day, called Raksha Bandhan, ..."[32] Religious scholar J. Gordon Melton describes it as "primarily a North Indian festival."[33] Leona M. Anderson and Pamela D. Young describe it as "one of the most popular festivals of North India."[34] Anthropologist David G. Mandelbaum has described it as "an annual rite observed in northern and western India."[35] Other descriptions of primary regions are of development economist Bina Agarwal ("In Northern India and Nepal this is ritualized in festivals such as raksha-bandhan."[2]), scholar and activist Ruth Vanita ("a festival widely celebrated in north India."[21]), anthropologist James D. Faubion ("In north India this brother-sister relationship is formalized in the ceremony of 'Rakshabandhan.'"[36]), and social scientist Prem Chowdhry ("... in the noticeable revival of the Raksha Bandhan festival and the renewed sanctity is has claimed in North India."[37]).

Evolution of Raksha Bandhan: the great and little traditions

"August 26, '44 My dear Lachi-Raja, After all your letter has come, and I feel greatly relieved. ... The Raksha and Janeoo mentioned in your present communication of 17th which you had sent on the occasion of Rakshabandhan got stranded somewhere, and have not yet arrived. There is little chance of their being recovered now. "

From a letter written by Indian nationalist Govind Ballabh Pant, to his children Laxmi Pant (nickname Lachi) and K. C. Pant (Raja), from Ahmednagar Fort prison on 26 August 1944.[38]

Sociologist Yogendra Singh has noted the contribution of American anthropologist McKim Marriott, to an understanding of the origins of the Raksha Bandhan festival.[39] In rural society, according to Marriott, there is steady interplay between two cultural traditions, the elite or "great," tradition based in texts, such as the Vedas in Indian society, and the local or "little," based in folk art and literature.[39] According to Singh, (Marriott) has shown that Raksha Bandhan festival has its "origin in the 'little tradition'." [39] Anthropologist Onkar Prasad has further suggested that Marriott was the first to consider the limitations within which each village tradition "operates to retain its essence."[40]

In his village study, Marriott described two concurrently observed traditions on the full moon day of Shravana: a "little tradition" festival called "Saluno," and a "great tradition" festival, Raksha Bandhan, but which Marriott calls, "Charm Tying:"

On Saluno day, many husbands arrive at their wives' villages, ready to carry them off again to their villages of marriage. But, before going off with their husbands, the wives as well as their unmarried village sisters express their concern for and devotion to their brothers by placing young shoots of barley, the locally sacred grain, on the heads and ears of their brothers. (The brothers) reciprocate with small coins. On the same day, along with the ceremonies of Saluno, and according to the literary precedent of the Bhavisyottara Purana, ... the ceremonies of Charm Tying (Rakhi Bandhan or Raksha Bandhan) are also held. The Brahman domestic priests of Kishan Garhi go to each patron and tie upon his wrist a charm in the form of a polychrome thread, bearing tassel "plums." Each priest utters a vernacular blessing and is rewarded by his patron with cash, ... The ceremonies of both now exist side by side, as if they were two ends of a process of primary transformation."[6]

Norwegian anthropologist, Øyvind Jaer, who did his fieldwork in eastern UP in the 1990s noted that the "great tradition" festival was in retreat and the "little tradition" one, involving sisters and brothers, now more important.[41]

Precedence in Hindu texts

Important in the Great Tradition is chapter 137 of the Uttara Parva of the Bhavishya Purana,[6] in which Lord Krishna describes to Yudhishthira the ritual of having a raksha (protection) tied to his right wrist by the royal priest (the rajpurohit) on the purnima (full moon day) of the Hindu lunar calendar month of Shravana).[42] In the crucial passage, Lord Krishna says,

"Parth (applied to any of the three sons of Kunti (also, Pritha), in particular, Yudhishthira): When the sky is covered with clouds, and the earth dark with new, tender, grass, in that very Shravana month's full moon day, at the time of sunrise, according to remembered convention, a Brahmin should take a bath with perfectly pure water. He should also according to his ability, offer libations of water to the gods, to the paternal ancestors, as prescribed by the Vedas for the task required to be accomplished before the study of the Vedas, to the sages, and as directed by the gods carry out and bring to a satisfactory conclusion the shradh ceremony to honor the deceased. It is commended that a Shudra should also make a charitable offering, and take a bath accompanied by the mantras. That very day, in the early afternoon (between noon and 3 PM) it is commended that a small parcel (bundle or packet) be prepared from a new cotton or silk cloth and adorned with whole grains of rice or barley, small mustard seeds, and red ocher powder, and made exceedingly wondrous, be placed in a suitable dish or receptacle. ... the purohit should bind this packet on the king's wrist with the words,'I am binding raksha (protection) to you with the same true words with which I bound Mahabali King of the Asuras. Always stay firm in resolve.' In the same manner as the king, after offering prayers to the Brahmins, the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras should conclude their Raksha Bandhan ceremony."[42]

Relation to territorial exogamy

Of special significance to married women, Raksha Bandhan is rooted in the practice of territorial- or village exogamy, in which a bride marries out of her natal village or town, and her parents, by custom, do not visit her in her married home.[9] Anthropologist Leo Coleman writes:

Rakhi and its local performances in Kishan Garhi were part of a festival in which connections between out-marrying sisters and village-resident brothers were affirmed. In the "traditional" form of this rite, according to Marriott, sisters exchanged with their brothers to ensure their ability to have recourse—at a crisis, or during childbearing—to their natal village and their relatives there even after leaving for their husband's home. For their part, brothers engaging in these exchanges affirmed the otherwise hard-to-discern moral solidarity of the natal family, even after their sister's marriage.[9]

In rural north India, where village exogamy is strongly prevalent, large numbers of married Hindu women travel back to their parents' homes every year for the ceremony.[10] Scholar Linda Hess writes:[11] Their brothers, who typically live with the parents or nearby, sometimes travel to their sisters' married home to escort them back. Many younger married women arrive a few weeks earlier at their natal homes and stay until the ceremony.[12] Folklorist Susan Wadley writes:

"In Savan, greenness abounds as the newly planted crops take root in the wet soil. It is a month of joy and gaiety, with swings hanging from tall trees. Girls and women swing high into the sky, singing their joy. The gaiety is all the more marked because women, especially the young ones, are expected to return to their natal homes for an annual visit during Savan.[12]

The brothers serve as lifelong intermediaries between their sisters' married- and parental homes,[13] as well as potential stewards of their security.

Urbanization, and mid-20th century transformations

The Hindu lunar calendar dates are below the English ones.

-

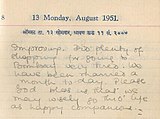

Shopping, 13 August 1951 (Shravana, 11th day, waxing moon). The Hindu lunar calendar dates are below the English ones.

-

Boards train for natal home, 15 August 1951. (Shravana, 13th day waxing moon)

-

Arrives at natal home 16 August 1951. (Shravana 14th day, waxing moon.)

-

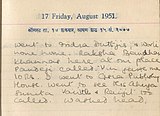

Raksha Bandhan, 17 August 1951. Receives Rupees 10 from her brother. (Shravana, last day, full moon.)

In his village study (1955), anthropologist McKim Marriott noted transformations of ritual that had begun to take place:

A further, secondary transformation of the festival of Charm Tying is also beginning to be evident in Kishan Garhi, for the thread charms of the priests are now factory-made in more attractive form ... A few sisters in Kishan Garhi have taken to tying these ... charms of priestly type onto their brothers' wrists. The new string charms are also more convenient for mailing in letters to distant, city-dwelling brothers whom sisters cannot visit on the auspicious day. Beals reports, furthermore, that brothers in the electrified village of Namhalli near Bangalore tuned in to All India Radio in order to receive a time signal at the astrologically exact moment, and then tied such charms to their own wrists, with an accompaniment of broadcast Sanskrit mantras."[6]

In urban India, where families are increasingly nuclear, and marriages not always traditional, the festival has become more symbolic, but continues to be highly popular. The rituals associated with these rites, however, have spread beyond their traditional regions and have been transformed through technology and migration,[14] According to anthropologist, Leo Coleman:

In modern rakhi, technologically mediated and performed with manufactured charms, migrating men are the medium by which the village women interact, vertically, with the cosmopolitan center—the site of radio broadcasts, and the source of technological goods and national solidarity.[14]

Hindi movies have played a salient role.[15] According to author Vaijayanti Pandit,

Raksha Bandhan traditionally celebrated in North India has acquired greater importance due to Hindi films. Lightweight and decorative rakhis, which are easy to post, are needed in large quantities by the market to cater to brothers and sisters living in different parts of the country or abroad."[15]

More social interaction among India's population has played a role in the increased celebration of this festival.[16] According to author Renuka Khandekar:

But since independence and the gradual opening up of Indian society, Raksha Bandhan as celebrated in North India has won the affection of many South Indian families. For this festival has the peculiar charm of renewing sibling bonds."[16]

The festival has also been promoted by Hindu political organizations.[17] According to authors P. M. Joshy and K. M. Seethi.

The RSS employs a cultural strategy to mobilise people through festivals. It observes six major festivals in a year. ... Till 20 years back, festivals like Raksha Bandhan' were unknown to South Indians. Through Shakha's intense campaign, now they have become popular in the southern India. In colleges and schools tying `Rakhi'—the thread that is used in the 'Raksha Bandhan'—has become a fashion and this has been popularised by the RSS and ABVP cadres.[17]

Similarly, according to author Christophe Jaffrelot,[18]

This ceremony occurs in a cycle of six annual festivals which often coincides with those observed in Hindu society, and which Hedgewar inscribed in the ritual calendar of his movement: Varsha Pratipada (the Hindu new year), Shivajirajyarohonastava (the coronation of Shivaji), guru dakshina, Raksha Bandhan (a North Indian festival in which sisters tie ribbons round the wrists of their brothers to remind them of their duty as protectors, a ritual which the RSS has re-interpreted in such a way that the leader of the shakha ties a ribbon around the pole of the saffron flag, after which swayamsevaks carry out this ritual for one another as a mark of brotherhood),[18]

Finally, the nation state in India has itself promoted this festival.[14] as Leo Coleman states:

... as citizens become participants in the wider "new traditions" of the national state. Broadcast mantras become the emblems of a new level of state power and the means of the integration of villagers and city dwellers alike into a new community of citizens.[19]

More recently, after enactment of more gender-neutral inheritance laws in India, it has been suggested that in some communities the festival has seen a resurgence of celebration, which is serving to indirectly pressure women to abstain from fully claiming their inheritance.[37] According to author Prem Chowdhry,

Rural patriarchal forces have been anxiously devising means to stem the progressive fallout of this Act through a variety of means. One way has been to oppose the inheritance rights of a daughter or a sister to those of the brother. Except in cases where there are no brothers, the sisters either sign away their in favour of their brother or sell it to him at a nominal price. This code of conduct is observed knowingly by both the natal and conjugal families. Brother-sister bonds of love have also been greatly encouraged, visible in the noticeable revival of the Raksha Bandhan festival and the renewed sanctity it has claimed in north India.[37]

Voluntary kin relations

Among women and men who are not blood relatives, there is also a transformed tradition of voluntary kin relations, achieved through the tying of rakhi amulets, which have cut across caste and class lines,[20] and Hindu and Muslim divisions.[21] In some communities or contexts, other figures, such as a matriarch, or a person in authority, can be included in the ceremony in ritual acknowledgement of their benefaction.[22] According to author Prem Chowdhry, "The same symbolic protection is also requested from the high caste men by the low caste women in a work relationship situation. The ritual thread is offered, though not tied and higher caste men customarily give some money in return."[22]

Regional variations in ritual

While Raksha Bandhan is celebrated in various parts of South Asia, different regions mark the day in different ways.

In the state of West Bengal and Odisha, this day is also called Jhulan Purnima. Prayers and puja of Lord Krishna and Radha are performed there. Sisters tie rakhi to brothers and wish immortality. Political parties, offices, friends, schools to colleges, street to palace celebrate this day with a new hope for a good relationship.[citation needed]

In Maharashtra, the festival of Raksha Bandhan is celebrated along with Narali Poornima (coconut day festival). Kolis are the fishermen community of the coastal state. The fishermen offer prayers to Lord Varuna, the Hindu god of Sea, to invoke his blessings. As part of the rituals, coconuts were thrown into the sea as offerings to Lord Varuna. The girls and women tie rakhi on their brother's wrist, as elsewhere.[43][44]

In the regions of North India, mostly Jammu, it is a common practice to fly kites on the nearby occasions of Janamashtami and Raksha Bandhan. It's not unusual to see the sky filled with kites of all shapes and sizes, on and around these two dates. The locals buy kilometres of strong kite string, commonly called as "gattu door" in the local language, along with a multitude of kites.[citation needed]

In Haryana, in addition to celebrating Raksha Bandhan, people observe the festival of Salono.[45] Salono is celebrated by priests solemnly tying amulets against evil on people's wrists.[46] As elsewhere, sisters tie threads on brothers with prayers for their well being, and the brothers give her gifts promising to safeguard her.[47]

In Nepal, Raksha Bandhan is referred to as Janai Purnima or Rishitarpani, and involves a sacred thread ceremony. It is observed by both Hindus and Buddhists of Nepal.[48] The Hindu men change the thread they wear around their chests (janai), while in some parts of Nepal girls and women tie rakhi on their brother's wrists. The Raksha Bandhan-like brother sister festival is observed by other Hindus of Nepal during one of the days of the Tihar (or Diwali) festival.[49]

The festival is observed by the Shaiva Hindus, and is popularly known in Newar community as Gunhu Punhi.[50]

Depictions in movies and popular history

The religious myths claimed Raksha Bandhan are disputed, and the historical stories associated with it considered apocryphal by some historians.

Jai Santoshi Maa (movie)

Ganesha had two sons, Shubha and Labha. The two boys become frustrated that they have no sister to celebrate Raksha Bandhan with. They ask their father Ganesha for a sister, but to no avail. Finally, saint Narada appears who persuades Ganesha that a daughter will enrich him as well as his sons. Ganesha agreed, and created a daughter named Santoshi Maa by divine flames that emerged from Ganesh's wives, Riddhi (Amazing) and Siddhi (Perfection). Thereafter, Shubha Labha (literally "Holy Profit") had a sister named Santoshi Maa (literally "Goddess of Satisfaction"), to tie Rakhi over Raksha Bandhan.[51] According to author Robert Brown

... in Varanasi the paired figures were usually called Rddhi and Siddhi, Ganeea's relationship to them was often vague. He was their malik, their owner; they were more often dasis than patnis (wives). Yet Ganesha was married to them, albeit within a marriage different from other divine matches in the lack of a clear familial context. Such a context has recently emerged in the popular film Jai Santoshi Ma. The film builds upon a text, also of recent vintage, in which Ganesha has a daughter, the neophyte goddess of satisfaction, Santoshi Ma. In the film, the role of Gane§a as family man is developed significantly. Santoshi Ma's genesis occurs on Rasa bandan. Ganesha's sister is visiting for the tying of the rakhi. He calls her bahenmansa — his "mind-born" sister. Ganesha's wives, Rddhi and Siddhi, are also present, with their sons Subha and Labha. The boys are jealous, as they, unlike their father, have no sister with whom to tie the rakhi. They and the other women plead with their father, but to no avail; but then Narada appears and convinces Ganesha that the creation of an illustrious daughter will reflect much credit back onto himself. Ganesha assents and from Rddhi and Siddhi emerges a flame that engenders Santoshi Ma.

Sikandar (movie, 1939)

Film historian Arthur Pomeroy describes the manufacture of a modern and widespread Indian legend in the 1939 movie Sikandar:[52]

In Sikandar a very daring Roxane follows Alexander incognito to India and manages to gain admission to King Porus (in the Indian version: Puru), a conversation with a young, friendly Indian village woman named Surmaniya, Roxane learns about the Indian feast of Rakhi which is being celebrated at that very moment with the purpose of strengthening the bond between sister and brother (0:25-0:30). On this occasion, sisters tie a ribbon (i.e. rakhi) to their brothers' arms to symbolize their close relationships, and brothers offer presents and assistance in return. Besides, Roxane is also told that the relationship need not be one of consanguinity; every girl can choose a brother. Therefore, she decides to offer the rakhi to King Porus, who accepts the relationship after some hesitation, because he feels the need to apologize to Roxane, Darius's (a.k.a. Dara's) daughter, for not having helped her father when he asked for assistance against Alexander. As a result of their bond, he offers her gifts befitting her rank and promises not to harm Alexander (0:32-35). Later, when Porus comes into hand-to-hand combat with the Greek king, he stands by his promise and spares him (1:31). Interestingly, the rakhi episode with Porus is still to this day very popular in India and is cited as very early historical evidence for the origin of the authentic Hindu festival called Raksha Bandhan. Although examples of that legend can be traced in internet forums, Indian newspapers, a children's book and an educational video, I was not able to find its ancient origin.

Rani Karnavati and Emperor Humayun

Bound by a sacred gift, in happier hours,

To prove a brother's undecaying faith;

Now when the star of Kurnivati lowers,

He rushes on to danger or to death.

He came to the beleaguered walls too late,

Vain was the splendid sacrifice to save;

Famine and death were sitting at the gate,

The flower of Rajasthan had found a grave.[53][54]

Another controversial historical account is that of Rani Karnavati of Chittor and Mughal Emperor Humayun, which dates to 1535 CE. When Rani Karnavati, the widowed queen of the king of Chittor, realised that she could not defend against the invasion by the Sultan of Gujarat, Bahadur Shah, she sent a rakhi to Emperor Humayun. The Emperor, according to one version of the story, set off with his troops to defend Chittor. He arrived too late, and Bahadur Shah had already captured the Rani's fortress. Alternative accounts from the period, including those by historians in Humayun's Mughal court, do not mention the rakhi episode and some historians have expressed skepticism whether it ever happened.[55] Historian Satish Chandra wrote,

... According to a mid-seventeenth century Rajasthani account, Rani Karnavati, the Rana's mother, sent a bracelet as rakhi to Humayun, who gallantly responded and helped. Since none of the contemporary sources mention this, little credit can be given to this story ...

Humayun's own memoirs never mention this, and give different reasons for his war with Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat in 1535.[56]

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Footnotes

References

Notes

- ^ "Rakhi 2019 - When is Rakhi?" (in dmy-all). Society for the Confluence of Festivals in India. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c Agarwal, Bina (1994), A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-0-521-42926-9

- ^ McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2 Quote: m Hindi rakśābandhan held on the full moon of the month of Savan, when sisters tie a talisman (rakhi q.v.) on the arm of their brothers and receive small gifts of money from them.

- ^ a b Berreman, Gerald Duane (1963), Hindus of the Himalayas, University of California Press, pp. 390–, GGKEY:S0ZWW3DRS4S Quote: Rakri: On this date Brahmins go from house to house tying string bracelets (rakrī) on the wrists of household members. In return the Brahmins receive from an anna to a rupee from each household. ... This is supposed to be auspicious for the recipient. ... It has no connotation of brother-sister devotion as it does in some plains areas. It is readily identified with Raksha Bandhan.

- ^ Gnanambal, K. (1969), Festivals of India, Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, p. 10 Quote: In North India, the festival is popularly called Raksha Bandhan ... On this day, sisters tie an amulet round the right wrists of brothers wishing them long life and prosperity. Family priests (Brahmans) make it an occasion to visit their clientiele to get presents.

- ^ a b c d e Marriott, McKim (1955), "Little Communities in an Indigenous Civilization", in McKim Marriott (ed.), Village India: Studies in the Little Community, University of Chicago Press, pp. 198–202

- ^ Wadley, Susan S. (27 July 1994), Struggling with Destiny in Karimpur, 1925-1984, University of California Press, pp. 84, 202, ISBN 978-0-520-91433-9 Quote: (p 84) Potters: ... But because the festival of Saluno takes place during the monsoon when they can't make pots, they make pots in three batches ...

- ^ Lewis, Oscar (1965), Village Life in Northern India: Studies in a Delhi Village, University of Illinois Press, p. 208

- ^ a b c Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 127, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: Rakhi and its local performances in Kishan Garhi were part of a festival in which connections between out-marrying sisters and village-resident brothers were affirmed. In the "traditional" form of this rite, according to Marriott, sisters exchanged with their brothers to ensure their ability to have recourse—at a crisis, or during childbearing—to their natal village and their relatives there even after leaving for their husband's home. For their part, brothers engaging in these exchanges affirmed the otherwise hard-to-discern moral solidarity of the natal family, even after their sister's marriage.

- ^ a b Goody, Jack (1990), The Oriental, the Ancient and the Primitive: Systems of Marriage and the Family in the Pre-Industrial Societies of Eurasia, Cambridge University Press, p. 222, ISBN 978-0-521-36761-5 Quote: "... the heavy emphasis placed on the continuing nature of brother-sister relations despite the fact that in the North marriage requires them to live in different villages. That relation is celebrated and epitomised in the annual ceremony of Rakśābandhan in northern and western India. ... The ceremony itself involves the visit of women to their brothers (that is, to the homes of their own fathers, their natal homes)

- ^ a b Hess, Linda (2015), Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in North India, Oxford University Press, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-937416-8 Quote: "In August comes Raksha Bandhan, the festival celebrating the bonds between brothers and sisters. Married sisters return, if they can, to their natal villages to be with their brothers.

- ^ a b c Wadley, Susan Snow (2005), Essays on North Indian Folk Traditions, Orient Blackswan, p. 66, ISBN 978-81-8028-016-0 Quote: In Savan, greenness abounds as the newly planted crops take root in the wet soil. It is a month of joy and gaiety, with swings hanging from tall trees. Girls and women swing high into the sky, singing their joy. The gaiety is all the more marked because women, especially the young ones, are expected to return to their natal homes for an annual visit during Savan.

- ^ a b Gnanambal, K. (1969), Festivals of India, Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, p. 10

- ^ a b c d Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 148, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: In modern rakhi, technologically mediated and performed with manufactured charms, migrating men are the medium by which the village women interact, vertically, with the cosmopolitan center—the site of radio broadcasts, and the source of technological goods and national solidarity Cite error: The named reference "Coleman2017-technology-migration" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Pandit, Vaijayanti (2003), BUSINESS @ HOME, Vikas Publishing House, p. 234, ISBN 978-81-259-1218-7 Quote: "Quote: Raksha Bandhan traditionally celebrated in North India has acquired greater importance due to Hindi films. Lightweight and decorative rakhis, which are easy to post, are needed in large quantities by the market to cater to brothers and sisters living in different parts of the country or abroad." Cite error: The named reference "Pandit 2003" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Khandekar, Renuka N. (2003), Faith: filling the God-sized hole, Penguin Books, p. 180 Quote: "But since independence and the gradual opening up of Indian society, Raksha Bandhan as celebrated in North India has won the affection of many South Indian families. For this festival has the peculiar charm of renewing sibling bonds." Cite error: The named reference "Khandekar2003" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Joshy, P. M.; Seethi, K. M. (2015), State and Civil Society under Siege: Hindutva, Security and Militarism in India, SAGE Publications, p. 112, ISBN 978-93-5150-383-5 Quote:(p 111) The RSS employs a cultural strategy to mobilise people through festivals. It observes six major festivals in a year. ... Till 20 years back, festivals like Raksha Bandhan were unknown to South Indians. Through Shakha's intense campaign, now they have become popular in the southern India. In colleges and schools tying `Rakhi'—the thread that is used in the 'Raksha Bandhan'—has become a fashion and this has been popularised by the RSS and ABVP cadres. Cite error: The named reference "JoshySeethi2015" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s : Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India), Penguin Books, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-14-024602-5 Quote: This ceremony occurs in a cycle of six annual festivals which often coincides with those observed in Hindu society, and which Hedgewar inscribed in the ritual calendar of his movement: Varsha Pratipada (the Hindu new year), Shivajirajyarohonastava (the coronation of Shivaji), guru dakshina, Raksha Bandhan (a North Indian festival in which sisters tie ribbons round the wrists of their brothers to remind them of their duty as protectors, a ritual which the RSS has re-interpreted in such a way that the leader of the shakha ties a ribbon around the pole of the saffron flag, after which swayamsevaks carry out this ritual for one another as a mark of brotherhood), ....

- ^ a b Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 148, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: ... as citizens become participants in the wider "new traditions" of the national state. Broadcast mantras become the emblems of a new level of state power and the means of the integration of villagers and city dwellers alike into a new community of citizens

- ^ a b Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L. (1996), India: A Country Study, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 246, ISBN 978-0-8444-0833-0

- ^ a b c Vanita, Ruth (2002), "Dosti and Tamanna: Male-Male Love, Difference, and Normativity in Hindi Cinema", in Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (eds.), Everyday Life in South Asia, Indiana University Press, pp. 146–158, 157, ISBN 978-0-253-34080-1

- ^ a b c Chowdhry, Prem (1994), The Veiled Women: Shifting Gender Equations in Rural Haryana, Oxford University Press, pp. 312–313, ISBN 978-0-19-567038-7 Quote: The same symbolic protection is also requested from the high caste men by the low caste women in a work relationship situation. The ritual thread is offered, though not tied and higher caste men customarily give some money in return.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary,Third Edition, 2008

- ^ Forbes, Duncan (1857), A dictionary, Hindustani and English, accompanied by a reversed dictionary, English and Hindustani, London: S. Low, Marston, p. 474

- ^ John T. Platts (1884), A Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi and English, London: W. H. Allen and Co

- ^ Monier-Williams, M. (1899), A Sanskrit-English dictionary: Etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to Cognate Indo-European languages, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, p. 869

- ^ Pathak, Ramchandra, ed. (1976), Adarsh Hindi Shabdkosh, Varanasi: Bhargav Book Depot

- ^ McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2

- ^ Biswas, Sailendra (2000), Samsad Bengali-English dictionary. 3rd ed., Calcutta,: Sahitya Samsad

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Salimuddin, S.M.; Anjum, Suhail, eds. (2013), Oxford Urdu English Dictionary, Karachi: Oxford University Press

- ^ Goody, Jack (1990), The Oriental, the Ancient and the Primitive: Systems of Marriage and the Family in the Pre-Industrial Societies of Eurasia, Cambridge University Press, p. 222, ISBN 978-0-521-36761-5

- ^ Jackson, Michael (2012), Between One and One Another, University of California Press, p. 52, ISBN 978-0-520-95191-4

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2011), Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations, ABC-CLIO, pp. 733–, ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7

- ^ Anderson, Leona May; Young, Pamela Dickey (2004), Women and Religious Traditions, Oxford University Press, pp. 30–31, ISBN 978-0-19-541754-8

- ^ Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970), Society in India: Continuity and change, University of California Press, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1

- ^ Faubion, James (2001), The Ethics of Kinship: Ethnographic Inquiries, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 151–, ISBN 978-0-7425-7889-0

- ^ a b c Chowdhry, Prem (2000), "Enforcing cultural codes: Gender and violence in northern India", in Nair, Janaki; John, Mary E. (eds.), A Question of Silence: The Sexual Economies of Modern India, Zed Books, p. 356, ISBN 978-1-85649-892-0

- ^ Pant, Govind Ballabh (1998), Nanda, Bal Ram (ed.), Selected Works of Govind Ballabh Pant, Oxford University Press, p. 265, ISBN 978-0-19-564118-9 Explanatory Note: Rakshabandhan in 1944 fell on 4 August. His children had attempted to send him the ritually protective Raksha thread, given by a priest, to be worn around the right wrist, and a new Upanayana sacred thread "janeoo," which Brahmins, such as Pant, would traditionally begin wearing over their right shoulder on the Upakarma ritual day, the day before Raksha Bandhan.

- ^ a b c Singh, Yogendra (2010), Social Sciences: Communication, Anthropology, and Sociology, Longman, pp. 116–, ISBN 978-81-317-1883-4

- ^ Prasad, Onkar (2003), "Folk and Classical Traditions of Indian Civilization: A Study of their Boundary Maintenance Mechanism with Special Reference to Music", Journal of the Indian Anthropological Society, 38: 341 Quote: "Undeniably both the folk and the classical traditions of India have continuities in structure and content but the limitation with which each system operates to retain its essence either of folkishness or of classicallty seems to have been first realized by Marriott (1955) in his studies on rituals of Kishan Garhi village of Uttar Pradesh."

- ^ Jaer, Øyvind (1995), Karchana: lifeworld-ethnography of an Indian village, Scandinavian University Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-82-00-21507-3 Quote: Rakshabandhan ("charm tying"). This is another All-India related festival. The festival occurs ten days after Nag Panchami on the full moon (purnima) on the last day of the month of Savan (July/August). This festival marks, according to Hindu conceptions, the point of transition between the old and the new fasli, i.e. the agricultural year. This is emphasized by its popular name Salono, derived from the Persian Sal-i- nau - new year (Mukerji, 1918:91). Rakshabandhan also marks the transition from the rainy season to the autumn. Sisters will first take a ceremonial bath, make a rakhi (wristband of thread) and put it onto the hands of their brothers. In return, the brothers should give money and clothes. The performance of this sister-brother relationship is widespread in Karchana except among the Avarnas, where it is uncommon. The other part of the charm-tying festival is linked not to the family, but to the village community and the jajmani system. The Brahmin puruhit (family priest) will visit all his jajmans (clients) and put a rakhi onto their hands. In return, the jajmans will give sidha (gifts of flour or grain to Brahmins) and money to their family priest. As the jajmani system is in retreat, the family aspect is at present the most important part of the festival.

- ^ a b

Upadhyay, Baburam (translator) (2003), Bhavisha Mahapuranam with Hindi translation, Part 3, Allahabad: Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, pp. 516–518

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Victor J. Green (1978). Festivals and saints days: a calendar of festivals for school and home. Blandford. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-7137-0889-9.

- ^ B. A. Gupte (2000). Folklore of Hindu Festivals and Ceremonials. Shubhi. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-81-87226-48-2.

- ^ Kumar Suresh Singh, Madan Lal Sharma, A. K. Bhatia, Anthropological Survey of India (1994) Haryana

- ^ General, India Office of the Registrar (1 January 1965). "Census of India, 1961". Manager of Publications. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gupta, Shakti M. (1991). Festivals, Fairs, and Fasts of India. Clarion Books. pp. 16, 95–96. ISBN 978-8185120232. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Trilok Chandra Majupuria; S. P. Gupta (1981). Nepal, the land of festivals: religious, cultural, social, and historical festivals. S. Chand. p. 78.; Quote: "JANAI PURNIMA OR RAKSHA BANDHAN OR RISHITARPANI (The Sacred Thread Festival) This festival falls on the full- moon day of Shrawan, and is celebrated by both the Hindus and Buddhists."

- ^ Michael Wilmore (2008). Developing Alternative Media Traditions in Nepal. Lexington. pp. 196–198. ISBN 978-0-7391-2525-0.

- ^ "Raksha Bandhan being observed today". Gorkha Post. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Brown, Robert L. (1991), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, SUNY Press, p. 150, ISBN 978-0-7914-0656-4

- ^ Pomeroy, Arthur J. (2017), A Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome on Screen, Wiley, p. 428, ISBN 978-1-118-74144-3

- ^ Roberts, Emma (1832), Oriental Scenes, dramatic sketches and tales, with other poems, pp. 125–

- ^ Fhlathuin, Maire ni (2015), British India and Victorian Literary Culture, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 174–, ISBN 978-1-4744-0776-2

- ^ Satish Chandra (2005), Medieval India: from Sultanat to the Mughals, Volume 2, Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 978-81-241-1066-9, retrieved 16 August 2011

- ^ Humayun; Jauhar (Trans) (2013). The Tezkereh Al Vakiat; Or, Private Memoirs of the Moghul Emperor Humayun: Written in the Persian Language, by Jouher, a Confidential Domestic of His Majesty. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-1-108-05603-8.

Works cited

- Agarwal, Bina (1994), A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-0-521-42926-9

- Anderson, Leona May; Young, Pamela Dickey (2004), Women and Religious Traditions, Oxford University Press, pp. 30–31, ISBN 978-0-19-541754-8

- Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1959), Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V. S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary, Poona: Prasad Prakashan, p. 1152, ISBN 978-81-208-0567-5

- Chandra, Satish (2003), Essays on Medieval Indian History, Oxford University Press, p. 369, ISBN 978-0-19-566336-5

- Chowdhry, Prem (1994), The Veiled Women: Shifting Gender Equations in Rural Haryana, Oxford University Press, pp. 312–313, ISBN 978-0-19-567038-7

- Chowdhry, Prem (2000), "Enforcing cultural codes: Gender and violence in northern India", in Nair, Janaki; John, Mary E. (eds.), A Question of Silence: The Sexual Economies of Modern India, Zed Books, p. 356, ISBN 978-1-85649-892-0

- Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 127, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9

- Faubion, James (2001), The Ethics of Kinship: Ethnographic Inquiries, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 151–, ISBN 978-0-7425-7889-0

- Gnanambal, K. (1969), Festivals of India, Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, p. 10

- Hess, Linda (2015), Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in North India, Oxford University Press, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-937416-8

- Jackson, Michael (2012), Between One and One Another, University of California Press, p. 52, ISBN 978-0-520-95191-4

- Gokulsing, K. Moti; Dissanayake, Wimal, eds. (2009), Popular Culture in a Globalised India, Routledge, p. xix, ISBN 978-1-134-02307-3

- Goody, Jack (1990), The Oriental, the Ancient and the Primitive: Systems of Marriage and the Family in the Pre-Industrial Societies of Eurasia, Cambridge University Press, p. 222, ISBN 978-0-521-36761-5

- Mayer, Adrian C. (2003), Caste and Kinship in Central India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17567-8

- McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2

- Marriott, McKim (1955), "Little Communities in an Indigenous Civilization", in McKim Marriott (ed.), Village India: Studies in the Little Community, University of Chicago Press, pp. 198–202

- McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2

- Prasad, Leela (2012), "Anklets on the pyal", in Leela Prasad; Ruth B. Bottigheimer; Lalita Handoo (eds.), Gender and Story in South India, SUNY Press, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-7914-8125-7

- Pandit, Vaijayanti (2003), BUSINESS @ HOME, Vikas Publishing House, p. 234, ISBN 978-81-259-1218-7

- Khandekar, Renuka N. (2003), Faith: filling the God-sized hole, Penguin Books, p. 180

- Joshy, P. M.; Seethi, K. M. (2015), State and Civil Society under Siege: Hindutva, Security and Militarism in India, SAGE Publications, p. 112, ISBN 978-93-5150-383-5

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s : Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India), Penguin Books, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-14-024602-5

- Agarwal, Bina (1994), A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-0-521-42926-9

- Wadley, Susan Snow (2005), Essays on North Indian Folk Traditions, Orient Blackswan, p. 66, ISBN 978-81-8028-016-0

- Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L. (1996), India: A Country Study, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 246, ISBN 978-0-8444-0833-0

- Vanita, Ruth (2002), "Dosti and Tamanna: Male-Male Love, Difference, and Normativity in Hindi Cinema", in Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (eds.), Everyday Life in South Asia, Indiana University Press, pp. 146–158, 157, ISBN 978-0-253-34080-1

- Pomeroy, Arthur J. (2017), A Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome on Screen, Wiley, p. 428, ISBN 978-1-118-74144-3

- McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2

- Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1959), Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V. S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary, Poona: Prasad Prakashan, p. 1322, ISBN 978-81-208-0567-5

- McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, p. 859, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2

- Goody, Jack (1990), The Oriental, the Ancient and the Primitive: Systems of Marriage and the Family in the Pre-Industrial Societies of Eurasia, Cambridge University Press, p. 222, ISBN 978-0-521-36761-5

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011), Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations, ABC-CLIO, pp. 733–, ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7

- Anderson, Leona May; Young, Pamela Dickey (2004), Women and Religious Traditions, Oxford University Press, pp. 30–31, ISBN 978-0-19-541754-8

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970), Society in India: Continuity and change, University of California Press, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1

- Vanita, Ruth (2002), "Dosti and Tamanna: Male-Male Love, Difference, and Normativity in Hindi Cinema", in Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (eds.), Everyday Life in South Asia, Indiana University Press, pp. 146–158, 157, ISBN 978-0-253-34080-1

External links

- Raksha Bandhan Know India – Festivals, Government of India

- Raksha Bandhan Government of Odisha, India