Edward Hicks

Edward Hicks | |

|---|---|

Edward Hicks Painting the Peaceable Kingdom by Thomas Hicks, 1839 | |

| Born | April 4, 1780 |

| Died | August 23, 1849 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | American |

Edward Hicks (April 4, 1780 – August 23, 1849) was an American folk painter and distinguished religious minister of the Society of Friends (aka "Quakers"). He became a Quaker icon because of his paintings.

Biography

Early life

Edward Hicks was born in his grandfather's mansion at Attleboro (now Langhorne), in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. His parents were Anglican. Isaac Hicks, his father, was a Loyalist who was left without any money after the British defeat in the Revolutionary War. After young Edward's mother died when he was eighteen months old, Matron Elizabeth Twining – a close friend of his mother's – raised him as one of her own at their farm, known as the Twining Farm.[1] He apparently also resided at the David Leedom Farm.[2] She also taught him the Quaker beliefs, which had a great effect on the rest of his life.

At the age of thirteen Hicks began an apprenticeship to coach makers William and Henry Tomlinson. He stayed with them for seven years, during which he learned the craft of coach painting. In 1800 he left the Tomlinson firm to earn his living independently as a house and coach painter, and in 1801 he moved to Milford to work for Joshua C. Canby, a coach maker.[3]

At this stage of his life Hicks was, as he later wrote in his memoirs, "in my own estimation a weak, wayward young man ... exceedingly fond of singing, dancing, vain amusements, and the company of young people, and too often profanely swearing".[4] Dissatisfied with his life, he started to attend Quaker meetings regularly, and in 1803 he was accepted for membership in the Society of Friends. Later that same year he married a Quaker woman named Sarah Worstall.

Working career

In 1812 his congregation recorded him as a minister, and by 1813 he began traveling throughout Philadelphia as a Quaker preacher. To meet the expenses of traveling, and for the support of his growing family, Hicks decided to expand his trade to painting household objects and farm equipment as well as tavern signs. His painting trade was lucrative, but it upset some in the Quaker community, because it contradicted the plain customs they respected. In 1815 Hicks briefly gave up ornamental painting and attempted to support his family by farming, while also continuing with the plain, utilitarian type of painting that his Quaker neighbors thought acceptable.[5] His financial difficulties only increased, as utilitarian painting was less remunerative, and Hicks did not have the experience he needed to cultivate the land, or run a farm primarily on his own.

By 1816, his wife was expecting a fifth child. After a relative of Hicks, at the urging of Hicks' close friend John Comly, talked to him about painting again, Hicks resumed decorative painting. This friendly suggestion saved Hicks from financial disaster, and preserved his livelihood not as a Quaker Minister but as a Quaker artist.[6] Around 1820, Hicks made the first of his many paintings of The Peaceable Kingdom. Hicks' easel paintings were often made for family and friends, not for sale, and decorative painting remained his main source of income.[7]

In 1827 a schism formed within the Religious Society of Friends, between Hicksites (named after Edward Hicks' cousin Elias Hicks) and Orthodox Friends.[8] As new settlers swelled Pennsylvania's Quaker community, many branched off into sects whose differences sometimes conflicted with one another, which greatly discouraged Edward Hicks from continuing to preach.[9] Nonetheless, in his lifetime Hicks was better known as a minister than as a painter.[10] He is buried at Newtown Friends Meetinghouse Cemetery in Newtown Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Painting

Quaker beliefs prohibited a lavish life or having excessive quantities of objects or materials. Unable to maintain his work as a preacher and painter at the same time, Hicks transitioned into a life of painting, and he used his canvases to convey his beliefs. He was unconfined by rules of his congregation, and able to freely express what religion could not: the human conception of faith.[11]

Although it is not considered a religious image, Hicks' Peaceable Kingdom exemplifies Quaker ideals. Hicks painted 62 versions of this composition. The animals and children are taken from Isaiah 11:6–8 (also echoed in Isaiah 65:25), including the lion eating straw with the ox. Hicks used his paintings as a way to define his central interest, which was the quest for a redeemed soul. This theme was also from one of his theological beliefs.[12]

Hicks' work was influenced by a specific Quaker belief referred to as the Inner Light. George Fox and other founding Quakers had established and preached the Inner Light doctrine. Fox explained that along with scriptural knowledge, many individuals achieve salvation by yielding one's self-will to the divine power of Christ and the "Christ within". This "Christ in You" concept was derived from the Bible's Colossians 1:27. Hicks depicted humans and animals to represent the Inner Light's idea of breaking physical barriers (of difference between two individuals) to working and living together in peace. Many of his paintings further exemplify this concept with depictions of Native Americans meeting the settlers of Pennsylvania, with William Penn prominent among them.

Hicks admired Penn as an opponent of British power in America, and he hoped that Penn could help ensure reform. Like Penn, Hicks opposed Britain's hierarchy.[12] Hicks most esteemed Penn for establishing the treaty of Pennsylvania with the Native Americans, because it was a state that strongly fostered the Quaker community.[13]

Exhibition

Edward Hicks' first major exhibition took place in 1860 at Williamsburg, Virginia. It got mixed reviews due to Hicks' habit of repeating various arrangements over and over again. Hicks' earliest presentation of work was in 1826. Kingdoms of the Branch was at that time in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[11] Hicks used Penn and the Native Americans to paraphrase Isaiah's prophecy, in full.

His work often focused on religious subject matter while using current events to portray them. Hicks conveyed meaning through symbols,[14] and depicted predators (such as lions) and prey (such as lambs) next to each other to show a theme of peace. Peaceable Kingdoms of the Branch (1826–30), is now located in Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC. It is a notable example of Hicks' legacy.[15]

A special collection on Edward Hicks is among the holdings of the Newtown Historic Association.[16]

Works

Hicks' works display similarities from painting to painting. For example, his 1834 version of "Peaceable Kingdom" and 1845 version of "The Residence of David Twining" offer many comparisons (please see first two paintings displayed below). First, the right area of both paintings appears to be the most congested area, in which the size of each object seems to reflect its importance regardless of its position in space. Both paintings show humans and animals interacting together, and evoke a sense of community because the people are portrayed as trying to accomplish something. In the case of "Peaceable Kingdom", there are settlers in the background, signing a treaty with the Native Americans.

Calmness and peace, rather than abrupt action, characterize Hicks' compositions. Many of the shapes and forms in his work appear to be organic, flowing and soft. One must pay close attention to the gestures of individuals and animals in his paintings to derive meaning. Hicks uses small detail variations as a way to force viewers to pay attention to content because they are deliberate and purposeful.

Although none of his paintings are completely identical, there are certain compositional structures and patterns Hicks follows within all of his work. Although the space may appear shallow on the picture plane of these paintings, depth is created through objects and objects size, and secondarily by light and shadows. The foreground, middle ground and background are all defined by objects, animals, landscape, humans, and skylines.

Hicks almost always painted outdoor scenes, in which the light source is the sun or sky. The color schemes of his work are not complicated, and within a painting such as "Peaceable Kingdom" many of the colors have the same warmth or brown tone. This is another way that Hicks' tries to convey "uniformity" or peace. Most of these paintings are asymmetrically balanced, to reflect actions taking place between groups of people and animals within the work.

Gallery of major works

-

Washington at the Delaware, (c. 1849)

-

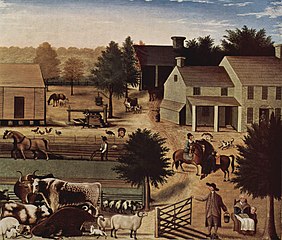

The Residence of David Twining, (1845–1848), Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection

-

Noah's Ark (1846), Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Penn's Treaty (1847), private collection

-

The Cornell Farm (1848), National Gallery of Art

Selected works and their locations

- The Residence of David Twining 1785, 1846, American Folk Art Museum, New York City

- The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1833, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

- The Falls of Niagara, c. 1825, and The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1830–32, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Penn's Treaty With the Indians, c. 1830–40, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

- Noah's Ark, 1846 and The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1844–46, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

- Grave of William Penn, 1847, Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey

- The Cornell Farm, 1848; The Grave of William Penn, c. 1847–48; The Landing of Columbus, c. 1837; The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1834; Penn's Treaty With the Indians, c. 1840–1l44; and Portrait of a Child, c. 1840, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- The Peaceable Kingdom, 1830–32, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, Alabama

- Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch, c. 1826–30, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

References

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Mr. A. Newton Gish (March 1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Twining Farm" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Elizabeth Gish and Leilani Stewart (1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: David Leedom Farm" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ^ Hicks 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Hicks 2009, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Weekley and Barry 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Miller and Mather. Edward Hicks, His Peaceable Kingdoms and Other Paintings. Newark: 1983.

- ^ Weekley and Barry 1999, p. 6.

- ^ Weekley and Barry 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Bauman, J. For The Reputation of Truth. London:1971

- ^ Weekley and Barry 1999, p. 34.

- ^ a b Saliner, Sharon. To Serve Well and Faithfully. London: 1862.

- ^ a b Hicks, E., & Mather, E. P. Edward Hicks: A gentle spirit. New York: Andrew Crispo Gallery Inc., 1975.

- ^ Morrison, C.M. Remember William Penn 1644. William Penn's Religion. Pennsylvania: 1703.

- ^ Vlach, John. Quaker Tradition and the Paintings of Edward A Strategy for the Study of Folk Art, JSTOR. New York: American Folk Society,1981.

- ^ Twinning. Hicks, 1780–1849. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller American Folk Art Museum, 2008.

- ^ "Newtown Historic Association website". Newtownhistoric.org. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

Sources

- Bauman, J. For The Reputation of Truth. London: 1971.

- Hicks, E., & Mather, E. P. Edward Hicks: A gentle spirit. New York: Andrew Crispo Gallery, 1975.

- Hicks, Edward, Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks late of Newtown. Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Written by himself. Philadelphia: Merrihew & Thomson. Printers. No. 7 Carter's Alley. 1851.

- Hicks, Edward, Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks. Applewood Books, 2009 ISBN 1-4290-1885-2,

- Morrison, C.M. Remember William Penn 1644. William Penn's Religion. Pennsylvania: 1703.

- Saliner, Sharon. To Serve Well and Faithfully. London: 1862.

- Twinning. Hicks, 1780–1849. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller American Folk Art Museum, 2008.

- Vlach, John. Quaker Tradition and the Paintings of Edward A Stratgey for the Study of Folk Art, JSTOR. New York: American Folk Society, 1981.

- Weekley, Carolyn J., and Laura Pass Barry. The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks. Williamsburg, Va: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1999.

Further reading

- Hicks, Edward. 2009. Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks. Applewood Books. ISBN 9781429018852

- Ford, Alice. 1998. Edward Hicks, Painter of the Peaceable Kingdom. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812216752

External links

- The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

- American Folk Art Museum in New York City

- The Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts

- The Philadelphia Museum of Art in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- The Newark Museum: American Art in Newark, New Jersey

- The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC

- Edward Hicks at Find a Grave

- Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina