Ambondro mahabo

| Ambondro mahabo Temporal range: Middle Jurassic

| |

|---|---|

| |

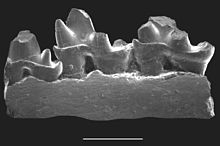

| Figure 1. Jaw of Ambondro, seen in lingual view (from the side of the tongue). Scale bar is 1 mm. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | Australosphenida |

| Family: | †Henosferidae |

| Genus: | †Ambondro Flynn et al., 1999 |

| Species: | †A. mahabo

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Ambondro mahabo Flynn et al., 1999

| |

Ambondro mahabo is a mammal from the middle Jurassic (about 167 million years ago) of Madagascar. The only species of the genus Ambondro, it is known from a fragmentary lower jaw with three teeth, interpreted as the last premolar and the first two molars. The premolar consists of a central czup with one or two smaller cusps and a cingulum (shelf) on the inner, or lingual, side of the tooth. The molars also have such a lingual cingulum. They consist of two groups of cusps: a trigonid of three cusps at the front and a talonid with a main cusp, a smaller cusp, and a crest at the back. Features of the talonid suggest that Ambondro had tribosphenic molars, the basic arrangement of molar features also present in marsupial and placental mammals. It is the oldest known mammal with putatively tribosphenic teeth; at the time of its discovery it antedated the second oldest example by about 25 million years.

Upon its description in 1999, Ambondro was interpreted as a primitive relative of Tribosphenida (marsupials, placentals, and their extinct tribosphenic-toothed relatives). In 2001, however, an alternative suggestion was published that united it with the Cretaceous Australian Ausktribosphenos and the monotremes (the echidnas, the platypus, and their extinct relatives) into the clade Australosphenida, which would have acquired tribosphenic molars independently from marsupials and placentals. The Jurassic Argentinean Asfaltomylos and Henosferus and the Cretaceous Australian Bishops were later added to Australosphenida, and new work on wear in australosphenidan teeth has called into question whether these animals, including Ambondro, did have tribosphenic teeth. Other paleontologists have challenged this concept of Australosphenida, and instead proposed that Ambondro is not closely related to Ausktribosphenos plus monotremes, or that monotremes are not australosphenidans and that the remaining australosphenidans are related to placentals.

Discovery and context

Ambondro mahabo was described by a team led by John Flynn in a 1999 paper in Nature. The scientific name derives from the village of Ambondromahabo, close to which the fossil was found. It is known from the Bathonian (middle Jurassic, about 167 million years ago) of the Mahajanga Basin in northwestern Madagascar, in the Isalo III unit, the youngest of the three rock layers that make up the Isalo "Group". This unit has also yielded crocodyliform and plesiosaur teeth and remains of the sauropod Lapparentosaurus.[1]

Description

Ambondro was described on the basis of a fragmentary right mandible (lower jaw) with three teeth in it (Figure 1), interpreted as the last premolar (p-last) and the first two molars (m1 and m2). It is in the collection of the University of Antananarivo as specimen UA 10602. Relative to other primitive mammals, it is small. Each of the teeth has a prominent cingulum (shelf) on the inner (lingual) side.[2] The p-last has a strong central cusp. There is a cuspule (small cusp) on the back of the tooth and probably another on the inner front corner. This tooth resembles the molars of symmetrodonts, a group of primitive mammals, but the back cusp is smaller than the metaconid of symmetrodonts.[3]

The front half of the m1 and m2 consists of the trigonid, a group of three cusps forming a triangle: the paraconid at the front on the inner side, protoconid in the middle on the outer (labial) side, and metaconid at the back on the inner side (see Figure 2). The three cusps form a right angle with each other at the protoconid, so that the trigonid is described as "open".[2] The paraconid is higher than the metaconid.[4] At the front margin, a cingulum is present that is divided into two small cusps.[5] Unlike in various early tribosphenic mammals and close relatives, there is no additional cuspule behind the metaconid.[6] At the back of the trigonid, the crest known as the distal metacristid is located relatively close to the outer side of the tooth and is continuous with another crest, the cristid obliqua, which is in turn connected to the back of the tooth.[2]

The talonid, another group of cusps, makes up the back of the tooth. It is wider than long[4] and contains a well-developed cusp, the hypoconid, on the outer side and a depression, the talonid basin, in the middle. The cristid obliqua connects to the hypoconid. The smaller hypoconulid cusp is present towards the inner side of the tooth, and the hypoconid and hypoconulid are connected by a cutting edge which is suggestive of the presence of a metacone cusp on the upper molars. Further towards the inner side, a crest, the entocristid, rims the talonid basin; on m1, it is swollen and on m2, it contains two small cuspules, but a distinct entoconid cusp is absent.[2] This entocristid is continuous with the lingual cingulum.[3]

Wear facets are areas of a tooth that show evidence of contact with a tooth in the opposing jaw when the teeth are brought together (known as occlusion).[7] Flynn and colleagues identified two wear facets at the front and back margins of the talonid basin; they argue that these wear facets suggest the presence of a protocone (another cusp on the outer side of the tooth) on the upper molars.[8] In a 2005 paper on Asfaltomylos, a related primitive mammal from Argentina, Thomas Martin and Oliver Rauhut disputed the presence of these wear facets within the talonid basin in Ambondro and instead identified wear facets on the cusps and crests surrounding the basin. They proposed that wear in the australosphenidan talonid occurs mainly on the rims, not in the talonid basin itself, and that australosphenidans may not have had a functional protocone.[9]

Interpretations

| Figure 3. Alternative views of the relationships of Ambondro. Top, Rougier et al., (2007, fig. 9): australosphenidans, including monotremes and Ambondro, are distinct from boreosphenidans.[Note 1] Bottom, Woodburne et al. (2003, fig. 3): australosphenidans, including Ambondro but excluding monotremes, are closely related to placentals. Many taxa are omitted from both trees for clarity. |

In their paper, Flynn and colleagues described Ambondro as the oldest mammal with tribosphenic molars—the basic molar type of metatherian (marsupials and their extinct relatives) and eutherian (placentals and their extinct relatives) mammals, characterized by the protocone cusp on the upper molars contacting the talonid basin on the lower molars in chewing. The discovery of Ambondro was thought to extend the known temporal range of tribosphenic mammals 25 million years further into the past.[10] Consequently, Flynn and colleagues argued against the prevailing view that tribosphenic mammals originated on the northern continents (Laurasia), and instead proposed that their origin lies in the south (Gondwana).[11] They cited the retention of a distal metacristid and an "open" trigonid as characters separating Ambondro from more modern tribosphenidans.[2]

In 2001, Zhe-Xi Luo and colleagues alternatively proposed that a tribosphenic molar pattern had arisen twice (compare Figure 3, top)—once giving rise to the marsupials and placentals (Boreosphenida), and once producing Ambondro, the Cretaceous Australian Ausktribosphenos, and the living monotremes, which first appeared in the Cretaceous (united as Australosphenida).[12] They characterized Australosphenida by the shared presence of a cingulum on the outer front corner of the lower molars, a short and broad talonid, a relatively low trigonid, and a triangulated last lower premolar.[13]

Also in 2001, Denise Sigogneau-Russell and colleagues in their description of the earliest Laurasian tribosphenic mammal, Tribactonodon, agreed with the relationship between Ausktribosphenos and monotremes, but argued that Ambondro was closer to Laurasian tribosphenidans than to Ausktribosphenos and monotremes. As evidence against the integrity of Australosphenida, they cited the presence of lingual cingula in various non-australosphenidan mammals; the presence of two cusps in the anterior cingulum in Ambondro as well as some boreosphenidans; the different appearance of the premolar in Ambondro (flat) and Ausktribosphenos (squared); and the contrast between the talonids of Ambondro (with a well-developed hypoconid on the labial side) and Ausktribosphenos (squared).[5]

The next year, Luo and colleagues published a more thorough analysis confirming their previous conclusion and adding the Cretaceous Australian Bishops to Australosphenida.[14] They mentioned the condition of the hypoconulid, which is inclined forward, rather than backward as in boreosphenidans, as an additional australosphenidan character[15] and noted that Ausktribosphenos and monotremes were united, to the exclusion of Ambondro, by the presence of a V-shaped notch in the distal metacristid.[16] In the same year, Asfaltomylos was described from the Jurassic of Argentina as another australosphenidan. In contrast to Ambondro, this animal lacked a distal metacristid and did not have as well-developed a lingual cingulum.[17]

However, in 2003 Michael Woodburne and colleagues revised the phylogenetic analysis published by Luo and colleagues, making several changes to the data, particularly in the monotremes.[18] Their results (Figure 3, bottom) challenged the division between Australosphenida and Boreosphenida, as proposed by Luo et al. Instead, they excluded monotremes from Australosphenida and placed the remaining australosphenidans close to Eutheria, with Ambondro most closely related to Asfaltomylos.[19] In 2007, Guillermo Rougier and colleagues described another australosphenidan, Henosferus, from the Jurassic of Argentina; they argued against a relationship between Eutheria and Australosphenida (Figure 3, top), but were ambivalent about the placement of monotremes within Australosphenida.[20] Based in part on Martin and Rauhut's earlier work on wear facets in australosphenidans, they questioned the presence of a true functional protocone on the upper molars of non-monotreme australosphenidans—none of which are known from upper teeth—and consequently suggested that australosphenidans may not, after all, have had truly tribosphenic teeth.[21]

Notes

- ^ Compare similar trees in Luo et al. (2001, fig. 1), Luo et al. (2002, fig. 1), Rauhut et al. (2002, fig. 3), which included fewer australosphenidan species.

References

- ^ Flynn et al., 1999, pp. 57–58

- ^ a b c d e Flynn et al., 1999, p. 58

- ^ a b Flynn et al., 1999, fig. 3

- ^ a b Rauhut et al., 2002, p. 167

- ^ a b Sigogneau-Russell et al., 2001, p. 146

- ^ Flynn et al., 1999, fig. 2

- ^ Luo et al., 2002, pp. 22, 29

- ^ Flynn et al., 1999, p. 59

- ^ Martin and Rauhut, 2005, pp. 422–423

- ^ Flynn et al., 1999, p. 57; Rougier et al., 2007, p. 23

- ^ Flynn et al., 1999, p. 60

- ^ Luo et al., 2001, p. 56

- ^ Luo et al., 2001, pp. 53, 56

- ^ Luo et al., 2002, fig. 1

- ^ Luo et al., 2002, p. 23

- ^ Luo et al., 2002, p. 22

- ^ Rauhut et al., 2002, p. 166

- ^ Woodburne, 2003, pp. 233–235

- ^ Woodburne, 2003, fig. 5; Woodburne et al., 2003, fig. 3

- ^ Rougier et al., 2007, p. 31

- ^ Rougier et al., 2007, pp. 24–25

Literature cited

- Flynn, J.J., Parrish, J.M., Rakotosamimanana, B., Simpson, W.F. and Wyss, A.R. 1999. A Middle Jurassic mammal from Madagascar (subscription required). Nature 401:57–60.

- Luo, Z.-X., Cifelli, R.L. and Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 2001. Dual origin of tribosphenic mammals (subscription required). Nature 409:53–57.

- Luo, Z.-X., Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. and Cifelli, R.L. 2002. In quest for a phylogeny of Mesozoic mammals. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 47(1):1–78.

- Martin, T. and Rauhut, O.W.M. 2005. Mandible and dentition of Asfaltomylos patagonicus (Australosphenida, Mammalia) and the evolution of tribosphenic teeth (subscription required). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(2):414–425.

- Rauhut, O.W.M., Martin, T., Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E. and Puerta, P. 2002. A Jurassic mammal from South America (subscription required). Nature 416:165–168.

- Rougier, G.W., Martinelli, A.G., Forasiepi, A.M. and Novacek, M.J. 2007. New Jurassic mammals from Patagonia, Argentina: A reappraisal of australosphenidan morphology and interrelationships. American Museum Novitates 3566:1–54.

- Sigogneau-Russell, D., Hooker, J.J. and Ensom, P.C. 2001. The oldest tribosphenic mammal from Laurasia (Purbeck Limestone Group, Berriasian, Cretaceous, UK) and its bearing on the 'dual origin' of Tribosphenida (subscription required). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Series IIA (Earth and Planetary Science) 333(2):141–147.

- Woodburne, M.O. 2003. Monotremes as pretribosphenic mammals (subscription required). Journal of Mammalian Evolution 10(3):195–248.

- Woodburne, M.O., Rich, T.H. and Springer, M.S. 2003. The evolution of tribospheny and the antiquity of mammalian clades (subscription required). Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution 28(2):360–385.