K2-18b

Artist's impression of K2-18b (right) orbiting red dwarf K2-18 (left). The unconfirmed exoplanet candidate K2-18c is shown between them. | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovery site | Kepler Space Observatory |

| Discovery date | 2015 |

| Transit | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| 0.1429+0.0060 −0.0065 au 21,380,000 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.20±0.08 |

| 32.939623+0.000095 −0.000100 d | |

| Inclination | 89.5785°+0.0079° −0.0088° |

| −0.10+0.81 −0.59 rad | |

| Semi-amplitude | 3.55+0.57 −0.58 m/s |

| Star | K2-18 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 2.71±0.07 R🜨[3] | |

| Mass | 8.63±1.35 M🜨[3] |

Mean density | 2.38 g/cm3 |

| ≤1.18 g | |

| Temperature | 265 ± 5 K (−8 ± 5 °C)[3] |

K2-18b, also known as EPIC 201912552 b, is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf K2-18, located 124 light-years (38 pc) away from Earth.[3] The planet, initially discovered through the Kepler Space Observatory, is about eight times the mass of Earth, thus is classified as a super Earth. It has a 33-day orbit within the star's habitable zone, but is unlikely to be habitable.

In 2019, two independent research studies, combining data from the Kepler space telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Hubble Space Telescope, concluded that there are significant amounts of water vapour in its atmosphere, a first for a planet in the habitable zone.[4][5][6]

Discovery

K2-18b was identified as part of the Kepler Space Observatory program, one of over 1,200 exoplanets discovered during the "Second Light" K2 mission.[7] The discovery of K2-18b was made in 2015, orbiting a red dwarf star (now known as K2-18) with a stellar spectral type of M2.8 about 124 light-years (38 pc) from Earth. The planet was detected through variations in the star's light curve caused by the transit of the planet in front of the star as seen from Earth.[3][8] The planet was designated 'K2-18b' as it was the eighteenth planet discovered during the K2 mission. The predicted relatively low contrast between the planet and its host star would make it easier to observe K2-18b's atmosphere in the future.[8]

In 2017, data from the Spitzer Space Telescope confirmed that K2-18b orbits in the habitable zone around K2-18 with a 33-day period, short enough to allow for observations of multiple K2-18b orbital cycles and improving the statistical significance of the signal. This led to widespread interest in continued observations of K2-18b.[9]

Later studies using the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) and the Calar Alto high-Resolution search for M dwarfs with Exoearths with Near-infrared and optical Echelle Spectrographs (CARMENES) instruments also identified a likely second exoplanet, K2-18c, with an estimated mass of 5.62±0.84 M🜨 in a tighter, 9-day orbit,[3] but this additional planet has not yet been confirmed, and may instead be a remnant of stellar activity.[2]

Location

K2-18's coordinates in the International Celestial Reference System are right ascension 11h 30m 14.518s, declination +07° 35′ 18.257″. This lies within the constellation of Leo, but outside its lion asterism.[10] When first discovered, K2-18's distance from Earth was estimated to be 110 light-years (34 pc).[8] However, more precise data from the Gaia star mapping project has shown K2-18 to be at a distance of 124.02 ± 0.26 light-years (38.025 ± 0.079 pc). This improved distance measurement helped to refine the properties of the exoplanetary system.[3]

Physical characteristics

K2-18b orbits K2-18 at about 0.1429 au (21.38 million km), which lies within the calculated habitable zone for the red dwarf, 0.12–0.25 au (18–37 million km).[6] The exoplanet has an orbital period of about 33 days,[9] which suggests it is tidally locked i.e. always shows the same face to its host star.[11] The planet's equilibrium temperature is estimated to be around 265 ± 5 K (−8 ± 5 °C),[3] due to its stellar irradiance of approximately 94% of Earth's.[9] K2-18b is estimated to have a radius of 2.71±0.07 R🜨 and a mass of 8.63±1.35 M🜨, based on analysis using HARPS and CARMENES instruments.[3] While it was initially considered a mini-Neptune on its 2015 discovery,[8] the improved data on K2-18b has classified it as a super-Earth,[9] although its size and density make it unlikely to be composed entirely of rocky iron and silicates; it is more likely to be composed of hydrogen, helium, and astronomical ices.[12] A comparison of K2-18b's size, orbit, and other features to other detected exoplanets suggests that the planet could support an atmosphere that contains additional gasses besides hydrogen and helium.[1]

-

Artist's animation of the K2-18 star system

-

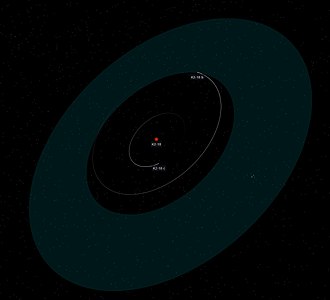

Diagram of the K2-18 planetary system, showing the orbits of K2-18b and the unconfirmed candidate K2-18c, and the star's habitable zone

Discovery of water

Further studies using the Hubble Space Telescope were performed, corroborating the results of the Kepler and Spitzer observations and allowing additional measurements of the planet's atmosphere. Two separate analyses of the Hubble data were published in 2019, led by researchers at the Université de Montréal and University College London (UCL). Both examined spectra of starlight passing through the planet's atmosphere during transits, finding that K2-18b has a hydrogen–helium atmosphere with a high concentration of water vapor, which could range from between 0.01% to 12.5%, up to between 20% and 50%, depending on what other gaseous species are present in the atmosphere. At the upper concentration levels, the water vapor would be sufficiently high to form clouds.[5][6][13] The UCL-led study was published on 11 September 2019 in the journal Nature Astronomy; the study led from the Université de Montréal, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was posted one day earlier on the preprint server arXiv.org.[11] The UCL-led analysis detected water with a statistical significance of 3.6 standard deviations, equivalent to a confidence level of 99.97%.[6]

This was the first super-Earth exoplanet within a star's habitable zone whose atmosphere was detected,[6] and the first discovery of water in a habitable-zone exoplanet.[4][5] Water had previously been detected in the atmospheres of non-habitable-zone exoplanets such as HD 209458 b, XO-1b, WASP-12b, WASP-17b, and WASP-19b.[14][15][16]

Astronomers emphasised that the discovery of water in the atmosphere of K2-18b does not mean the planet can support life or is even habitable, as it probably lacks any solid surface or an atmosphere that can support life.[4] Nevertheless, finding water in a habitable zone exoplanet helps understand how planets are formed.[4] K2-18b is now expected to be observed with the James Webb Space Telescope, due to launch in 2021, and the ARIEL space telescope, due to launch in 2028. Both will carry instruments designed to determine the composition of exoplanet atmospheres.[5]

See also

- Extraterrestrial liquid water – Liquid water naturally occurring outside Earth

- Habitability of red dwarf systems – Possible factors for life around red dwarf stars

- List of potentially habitable exoplanets

- List of potentially habitable moons – Measure of the potential of natural satellites to have environments hospitable to life

- Planetary habitability – Known extent to which a planet is suitable for life

References

- ^ a b Cloutier, R.; et al. (5 December 2017). "Characterization of the K2-18 multi-planetary system with HARPS. A habitable zone super-Earth and discovery of a second, warm super-Earth on a non-coplanar orbit". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 608 (35). A35. arXiv:1707.04292. Bibcode:2017A&A...608A..35C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731558. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Sarkis, Paula; et al. (2018). "The CARMENES Search for Exoplanets around M Dwarfs: A Low-mass Planet in the Temperate Zone of the Nearby K2-18". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (6): 257. arXiv:1805.00830. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..257S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aac108.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Cloutier, R.; et al. (7 January 2019). "Confirmation of the radial velocity super-Earth K2-18c with HARPS and CARMENES". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 621. A49. arXiv:1810.04731. Bibcode:2019A&A...621A..49C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Ghosh, Pallab (12 September 2019). "Water found for first time on 'potentially habitable' planet". BBC News. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d Greshko, Michael (11 September 2019). "Water found on a potentially life-friendly alien planet". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Tsiaras, Angelos; et al. (11 September 2019). "Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable-zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b". Nature Astronomy: 1–6. arXiv:1909.05218. Bibcode:2019arXiv190905218T. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0878-9. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "NASA's Kepler Mission Announces Largest Collection of Planets Ever Discovered" (Press release). NASA. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d Montet, Benjamin T.; et al. (5 August 2015). "Stellar and Planetary Properties of K2 Campaign 1 Candidates and Validation of 17 Planets, Including a Planet Receiving Earth-like Insolation". The Astrophysical Journal. 809 (1): 25. arXiv:1503.07866. Bibcode:2015ApJ...809...25M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/809/1/25.

- ^ a b c d Benneke, Björn; et al. (12 January 2017). "Spitzer Observations Confirm and Rescue the Habitable-zone Super-earth K2-18b for Future Characterization". The Astrophysical Journal. 834 (2): 187. arXiv:1610.07249. Bibcode:2017ApJ...834..187B. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/2/187.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "K2-18 -- High proper-motion Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b Wall, Mike (11 September 2019). "The Water Vapor Find on 'Habitable' Exoplanet K2-18 b Is Exciting — But It's No Earth Twin". Space.com. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

Tsiaras and his colleagues published their results today (Sept. 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy. The other research team, led by Björn Benneke of the Université de Montréal, posted its paper on the online preprint site arXiv.org Tuesday. The study by Benneke et al. has not yet been peer-reviewed.

- ^ Rogers, Leslie (2 March 2015). "Most 1.6 Earth-radius Planets Are Not Rocky". The Astrophysical Journal. 801 (1): 41. arXiv:1407.4457. Bibcode:2015ApJ...801...41R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/801/1/41.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (11 September 2019). "This may be the first known exoplanet with rain and clouds of water droplets". ScienceNews. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds". NASA. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Deming, D.; et al. (2013). "Infrared Transmission Spectroscopy of the Exoplanets HD 209458b and XO-1b Using the Wide Field Camera-3 on the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal. 774 (2): 95. arXiv:1302.1141. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...95D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/2/95.

- ^ Mandell, A. M.; et al. (2013). "Exoplanet Transit Spectroscopy Using WFC3: WASP-12 b, WASP-17 b, and WASP-19 b". The Astrophysical Journal. 779 (2): 128. arXiv:1310.2949. Bibcode:2013ApJ...779..128M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/779/2/128.

External links

- Benneke, Björn; et al. (2019). "Water Vapor on the Habitable-Zone Exoplanet K2-18b". arXiv:1909.04642 [astro-ph.EP].

- K2-18 b Confirmed Planet Overview Page NASA Exoplanet Archive