Star polygon

{5/2} |

|5/2| |

| A regular star pentagon, {5/2}, has five corner vertices and intersecting edges, while concave decagon, |5/2|, has ten edges and two sets of five vertices. The first are used in definitions of star polyhedra, while the second are used in planar tilings. | |

Small stellated dodecahedron |

Tessellation |

In geometry, a star polygon is a type of non-convex polygon. Only the regular star polygons have been studied in any depth; star polygons in general appear not to have been formally defined, however certain notable ones can arise through truncation operations on regular simple and star polygons.

Branko Grünbaum identified two primary definitions used by Kepler, one being the regular star polygons with intersecting edges that don't generate new vertices, and the second being simple isotoxal concave polygons.[1]

The first usage is included in polygrams which includes polygons like the pentagram but also compound figures like the hexagram.

Etymology

Star polygon names combine a numeral prefix, such as penta-, with the Greek suffix -gram (in this case generating the word pentagram). The prefix is normally a Greek cardinal, but synonyms using other prefixes exist. For example, a nine-pointed polygon or enneagram is also known as a nonagram, using the ordinal nona from Latin.[citation needed] The -gram suffix derives from γραμμή (grammḗ) meaning a line.[2]

Regular star polygon

{5/2} |

{7/2} |

{7/3}... |

A "regular star polygon" is a self-intersecting, equilateral equiangular polygon.

A regular star polygon is denoted by its Schläfli symbol {p/q}, where p (the number of vertices) and q (the density) are relatively prime (they share no factors) and q ≥ 2.

The symmetry group of {n/k} is dihedral group Dn of order 2n, independent of k.

Regular star polygons were first studied systematically by Thomas Bradwardine, and later Kepler.[3]

Construction via vertex connection

Regular star polygons can be created by connecting one vertex of a simple, regular, p-sided polygon to another, non-adjacent vertex and continuing the process until the original vertex is reached again.[4] Alternatively for integers p and q, it can be considered as being constructed by connecting every qth point out of p points regularly spaced in a circular placement.[5] For instance, in a regular pentagon, a five-pointed star can be obtained by drawing a line from the first to the third vertex, from the third vertex to the fifth vertex, from the fifth vertex to the second vertex, from the second vertex to the fourth vertex, and from the fourth vertex to the first vertex.

If q is greater than half of p, then the construction will result in the same polygon as p-q; connecting every third vertex of the pentagon will yield an identical result to that of connecting every second vertex. However, the vertices will be reached in the opposite direction, which makes a difference when retrograde polygons are incorporated in higher-dimensional polytopes. For example, an antiprism formed from a prograde pentagram {5/2} results in a pentagrammic antiprism; the analogous construction from a retrograde "crossed pentagram" {5/3} results in a pentagrammic crossed-antiprism. Another example is the tetrahemihexahedron, which can be seen as a "crossed triangle" {3/2} cuploid.

Degenerate regular star polygons

If p and q are not coprime, a degenerate polygon will result with coinciding vertices and edges. For example {6/2} will appear as a triangle, but can be labeled with two sets of vertices 1-6. This should be seen not as two overlapping triangles, but a double-winding of a single unicursal hexagon.[6][7]

Construction via stellation

Alternatively, a regular star polygon can also be obtained as a sequence of stellations of a convex regular core polygon. Constructions based on stellation also allow for regular polygonal compounds to be obtained in cases where the density and amount of vertices are not coprime. When constructing star polygons from stellation, however, if q is greater than p/2, the lines will instead diverge infinitely, and if q is equal to p/2, the lines will be parallel, with both resulting in no further intersection in Euclidean space. However, it may be possible to construct some such polygons in spherical space, similarly to the monogon and digon; such polygons do not yet appear to have been studied in detail.

Simple isotoxal star polygons

When the intersecting lines are removed, the star polygons are no longer regular, but can be seen as simple concave isotoxal 2n-gons, alternating vertices at two different radii, which do not necessarily have to match the regular star polygon angles. Branko Grünbaum in Tilings and Patterns represents these stars as |n/d| that match the geometry of polygram {n/d} with a notation {nα} more generally, representing an n-sided star with each internal angle α<180°(1-2/n) degrees.[1] For |n/d|, the inner vertices have an exterior angle, β, as 360°(d-1)/n.

| |n/d| {nα} |

{330°} |

{630°} |

|5/2| {536°} |

{445°} |

|8/3| {845°} |

|6/2| {660°} |

{572°} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 30° | 36° | 45° | 60° | 72° | ||

| β | 150° | 90° | 72° | 135° | 90° | 120° | 144° |

| Isotoxal star |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Related polygram {n/d} |

{12/5} |

{5/2} |

{8/3} |

2{3} Star figure |

{10/3} | ||

Examples in tilings

These polygons are often seen in tiling patterns. The parametric angle α (degrees or radians) can be chosen to match internal angles of neighboring polygons in a tessellation pattern. Johannes Kepler in his 1619 work Harmonices Mundi, including among other period tilings, nonperiodic tilings like that three regular pentagons, and a regular star pentagon (5.5.5.5/2) can fit around a vertex, and related to modern penrose tilings.[8]

| Star triangles | Star squares | Star hexagons | Star octagons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(3.3* α.3.3** α) |

(8.4* π/4.8.4* π/4) |

(6.6* π/3.6.6* π/3) |

(3.6* π/3.6** π/3) |

(3.6.6* π/3.6) |

Not edge-to-edge |

Interiors of star polygons

The interior of a star polygon may be treated in different ways. Three such treatments are illustrated for a pentagram. Branko Grunbaum and Geoffrey Shephard consider two of them, as regular star polygons and concave isogonal 2n-gons.[8]

These include:

- Where a side occurs, one side is treated as outside and the other as inside. This is shown in the left hand illustration and commonly occurs in computer vector graphics rendering.

- The number of times that the polygonal curve winds around a given region determines its density. The exterior is given a density of 0, and any region of density > 0 is treated as internal. This is shown in the central illustration and commonly occurs in the mathematical treatment of polyhedra. (However, for non-orientable polyhedra density can only be considered modulo 2 and hence the first treatment is sometimes used instead in those cases for consistency.)

- Where a line may be drawn between two sides, the region in which the line lies is treated as inside the figure. This is shown in the right hand illustration and commonly occurs when making a physical model.

When the area of the polygon is calculated, each of these approaches yields a different answer.

Star polygons in art and culture

Star polygons feature prominently in art and culture. Such polygons may or may not be regular but they are always highly symmetrical. Examples include:

- The {5/2} star pentagon (pentagram) is also known as a pentalpha or pentangle, and historically has been considered by many magical and religious cults to have occult significance.

- The {7/2} and {7/3} star polygons (heptagrams) also have occult significance, particularly in the Kabbalah and in Wicca.

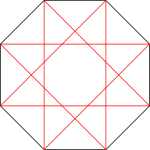

- The {8/3} star polygon (octagram), is frequent geometrical motifs in Mughal Islamic art and architecture; the first is on the emblem of Azerbaijan.

- An eleven pointed star called the hendecagram was used on the tomb of Shah Nemat Ollah Vali.

An {8/3} octagram constructed in a regular octagon |

Seal of Solomon with circle and dots (star figure) |

See also

- List of regular polytopes and compounds#Stars

- Star polyhedron, Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron, and uniform star polyhedron

- Regular star 4-polytope

- Magic star

- Star (glyph)

- Rub el Hizb

- Moravian star

- Pentagramma mirificum

References

- ^ a b Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, section 2.5

- ^ γραμμή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Coxeter, Introduction to Geometry, second edition, 2.8 Star polygons p.36-38

- ^ Coxeter, Harold Scott Macdonald (1973). Regular polytopes. Courier Dover Publications. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-486-61480-9.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Star Polygon". MathWorld.

- ^ Are Your Polyhedra the Same as My Polyhedra? Branko Grünbaum

- ^ Coxeter, The Densities of the Regular polytopes I, p.43: If d is odd, the truncation of the polygon {p/q} is naturally {2n/d}. But if not, it consistents of two coincident {n/(d/2)}'s; two, because each side arises from an original side and once from an original vertex. Thus the density of a polygon is unaltered by truncation.

- ^ a b Branko Grunbaum and Geoffrey C. Shephard, Tilings by Regular Polygons, Mathematics Magazine 50 (1977), 227–247 and 51 (1978), 205–206]

- ^ Tiling with Regular Star Polygons, Joseph Myers

- Cromwell, P.; Polyhedra, CUP, Hbk. 1997, ISBN 0-521-66432-2. Pbk. (1999), ISBN 0-521-66405-5. p. 175

- Grünbaum, B. and G.C. Shephard; Tilings and Patterns, New York: W. H. Freeman & Co., (1987), ISBN 0-7167-1193-1.

- Grünbaum, B.; Polyhedra with Hollow Faces, Proc of NATO-ASI Conference on Polytopes ... etc. (Toronto 1993), ed T. Bisztriczky et al., Kluwer Academic (1994) pp. 43–70.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strass, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 26. pp. 404: Regular star-polytopes Dimension 2)

- Branko Grünbaum, Metamorphoses of polygons, published in The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugène Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and its History, (1994)