Gabriel Báthory

| Gabriel Báthory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1608–1613 |

| Predecessor | Sigismund Rákóczi |

| Successor | Gabriel Bethlen |

| Born | August 15, 1589 Várad, Principality of Transylvania (now Oradea, Romania) |

| Died | October 27, 1613 (aged 24) Várad |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Anna Horváth Palocsai |

| Father | Stephen Báthory |

| Mother | Zsuzsanna Bebek |

| Religion | Calvinism |

Gabriel Báthory (Template:Lang-hu; 15 August 1589 – 27 October 1613) was Prince of Transylvania from 1608 to 1613. Born to the Roman Catholic branch of the Báthory family, he was closely related to four rulers of the Principality of Transylvania (a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire which had developed in the eastern territories of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary). His father, Stephen Báthory, held estates in the principality, but never ruled it. Being a minor when his father died in 1601, Gabriel became the ward of the childless Stephen Báthory, from the Protestant branch of the family, who converted him to Calvinism. After inheriting his guardian's most estates in 1605, Gabriel became one of the wealthiest landowners in Transylvania and Royal Hungary (a realm of the Habsburg Empire which included the northern and western parts of medieval Hungary).

Gabriel made an alliance with the Hajdús—irregular troops stationing along the borders of Transylvania and Royal Hungary—and laid claim to Transylvania against the elderly prince, Sigismund Rákóczi in February 1608. Rákóczi abdicated and the Diet of Transylvania elected Gabriel prince without resistance. Both the Sublime Porte and the Habsburg ruler Matthias II acknowledged Gabriel's election. He ignored the privileges of the Transylvanian Saxons and captured their wealthiest town, Szeben (now Sibiu in Romania), provoking an uprising in 1610. His attempts to expand his authority over the Ottoman vassal Wallachia and his negotiations with Matthias II outraged the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I. The Sultan decided to replace Gabriel with an exiled Transylvanian nobleman, Gabriel Bethlen, and sent troops to invade the principality in August 1613. Transylvania was unable to resist and the Diet dethroned Gabriel. He was murdered by Hajdú assassins.

Early life

Childhood

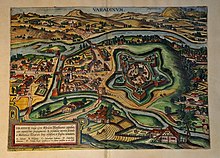

Báthory was born in Várad (now Oradea in Romania) before dawn on 15 August 1589.[1][2] His father, Stephen Báthory, was a cousin of Prince of Transylvania Sigismund Báthory.[3] Stephen was captain of Várad when Gabriel was born.[1] Gabriel's mother was his father's first wife, Zsuzsanna Bebek.[4] Although she had already given birth to four children, none survived infancy.[1] Sigismund Báthory dismissed Gabriel's father from Várad in the summer of 1592, and Gabriel's family then moved to the Báthorys' ancient castle in Szilágysomlyó (now Șimleu Silvaniei in Romania).[5]

The Principality of Transylvania emerged after the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in the 1540s.[6] The principality included the eastern and northeastern regions of the medieval kingdom[6] and its princes paid a yearly tribute to the Ottoman sultans.[7] The princes were elected by the Diet, but they were to seek the Ottoman sultans' confirmation to rule the principality.[8] The Habsburg kings of Royal Hungary regarded the principality as a part of their realm and the first rulers of the principality acknowledged the Habsburgs' claim in secret treaties in the 1570s.[9][10] The Diet of Transylvania comprised primarily of the representatives of the Three Nations (that is the Hungarian noblemen, the Saxon burghers and the Székelys).[11][12]

Sigismund Báthory, who was a devout Catholic,[13] wanted to join the Holy League of Pope Clement VIII against the Ottoman Empire, but most Transylvanian noblemen opposed his plan.[14] Stephen Báthory's brother, Balthasar, was an opposition leader.[14] Balthasar was captured and murdered at Sigismund's order in late August 1594.[14] Gabriel's father fled from Transylvania to Poland, leaving his family behind in Szilágysomlyó;[15] the five-year-old Gabriel was imprisoned with his mother and newborn sister, Anna.[5] Stephen and Balthasar's brother, Cardinal Andrew Báthory (who lived in Poland), persuaded Pope Clement VIII to intervene on their behalf.[16] Gabriel, his mother and sister were freed at the pope's request and were allowed to join Stephen in Poland.[16] His mother became seriously ill, and died near the end of 1595.[17][18]

The Ottomans routed the armies of the Holy League in a series of battles after 1595.[19] Sigismund Báthory abdicated in favor of Gabriel's uncle, Andrew, in early 1599 in the hope that Andrew could regain the Ottoman sultans' favor with Polish mediation.[20][21] Gabriel's father accompanied Andrew back to Transylvania, and his family followed him.[20] Michael the Brave, Prince of Wallachia, who had joined the Holy League, invaded Transylvania and defeated Andrew with the assistance of Székely troops.[22] After Székely commoners murdered Andrew, Michael the Brave took possession of Transylvania.[22] Gabriel's father fled to Kővár (now Remetea Chioarului in Romania) and swore fealty to the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph (who was also king of Hungary), before his death on 21 February 1601.[23]

| Báthorys in Transylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In guardianship

The orphaned Gabriel and Anna were placed in the guardianship of their father's childless cousin, Stephen Báthory, and lost most of their father's estates; Szilágysomlyó was seized by the royal treasury, and their scattered estates in Szatmár, Szabolcs and Kraszna Counties were seized by a distant cousin, Peter Szaniszlófi.[24] Scholar János Czeglédi educated Gabriel in Nagyecsed, and the wealthy Stephen Báthory converted Gabriel from Catholicism to Calvinism.[25] Gabriel pledged that he would expel Catholics, Lutherans and Unitarians from his estates.[26] The young Gabriel's strength was legendary, and he was said to break horseshoes with his bare hands.[2]

Rudolf's troops occupied Transylvania in 1603 and his officials started to confiscate the estates of noblemen through legal procedeeings on false charges of treason.[27] One of the wealthiest landowners, Stephen Bocskai, was accused of maintaining secret correspondence with Transylvanian exiles in 1604.[27] To avoid imprisonment, he rose up in open rebelion with the backing of the Hajdú, irregular troops stationed along the borders of Transylvania and Royal Hungary.[28][29] Although Stephen Báthory did not openly support Bocskai, he sent Gabriel to Bocskai's court in Kassa.[30][29] Sixteen-year-old Gabriel participated in a battle against the royal army near Sárospatak in early February 1605; three years later, poet János Rimay accused him of fleeing the battlefield.[31] Rimay also said that Gabriel spent his days mainly drinking wine and allegedly had an affair with his aunt, Kata Iffjú (who was over thirty years old at the time).[32]

Rise to power

Bocskai was elected prince of Transylvania on 21 February 1605 and prince of Hungary on 20 April of that year.[33] His realm included most of Transylvania proper, Partium and Upper Hungary.[34] Stephen Báthory died on 25 July 1605.[35] He had willed most of his estates to Gabriel, who became one of the wealthiest noblemen in Bocskai's realm.[36] Bocskai hinted that he regarded Gabriel as his successor, ordering Bálint Drugeth (commander-in-chief of his army in Upper Hungary) to "hold Gabriel Báthory in the highest esteem among the Hungarian lords" if he did not return from his meeting with Ottoman Grand Vizier Lala Mehmed Pasha[37] in November 1605.[38] Young noblemen (including Gabriel's future enemy, Gabriel Bethlen) and military officials also supported Gabriel.[38] Years later, Gáspár Bojti Veres wrote that Gabriel hosted feasts to win popularity with Bocskai's courtiers and commanders.[38] Gabriel's relatives, Mihály Káthay (Bocskai's chancellor) and János Imreffy (Kata Iffjú's husband), were his principal supporters.[39] His position weakened after Bocskai who was taken ill suddenly had Káthay imprisoned for treason in early September 1606.[40] Káthay's opponents, Simon Péchi and János Rimay, persuaded the dying (and often unconscious) Bocskai to name Bálint Drugeth his successor in his last will.[41]

Bocskai died in Kassa on 29 December 1606.[42] A mob accused Káthay of poisoning Bocskai, and lynched him on 12 January 1607.[43] Gabriel had demanded the Principality of Transylvania in a 2 January 1607 letter to the grand vizier, Kuyucu Murad Pasha.[43] Bocskai's deputy, the elderly Sigismund Rákóczi, continued to administer the principality with the consent of the Diet of Transylvania.[44] Gabriel sent Bethlen to Székely captain János Petki to secure his support, but Bethlen was imprisoned at Rákóczi's order on 26 January.[45] Rákóczi also dismissed Várad captain Dénes Bánffy, the fiancé of Gabriel's sister Anna.[46]

The delegates of the Three Nations of Transylvania wanted to demonstrate their right to freely elect the prince.[47] The Diet first passed a decree prohibiting a minor from being elected prince, preventing Gabriel's election.[48] It ignored Bocskai's last will, electing Rákóczi prince on 12 February.[47] Gabriel mustered troops, saying that he only wanted to protect Transylvania.[49] He demanded the cancellation of the Transylvanian decrees ordering the confiscation of his father and uncles' estates in 1595.[50] Gabriel approached Rudolph I's councillors after the Diet expelled the Jesuits from Transylvania, offering to defend the Catholic Church in the principality if he ascended the throne and saying that he was ready to reconvert to Catholicism.[51][52] Rudolph made him governor of Transylvania in June, but the appointment had no real effect on Gabriel's position.[52] Gabriel married Bocskai's kinswoman, Anna Horváth Palocsai, about two months later.[53]

After being unpaid for months, the Hajdús rose up in the autumn of 1607.[54] They offered their support to Drugeth, who refused to lead them.[54] Gabriel also treated them with disdain and promised to protect Transylvania against them at the end of October.[55] He soon mustered his troops and marched to Upper Hungary.[55] He again approached the royal court, asking Rudolph to make him voivode of Transylvania.[52] After the representatives of the Hajdús and the noblemen of Upper Hungary made a fifty-day truce in Ináncs at the end of the year, Gabriel began negotiations with the Hajdús.[55] They concluded a treaty on 8 February 1608.[56][57] Gabriel pledged to grant villages to the Hajdús in Partium, and they promised to support him in seizing Transylvania.[58][59] He also promised to expel "heretics and idolaters" (Unitarians and Catholics) from the royal council.[58][59] According to the contemporary Ferenc Nagy Szabó's memoirs, the Ottoman grand vizier soon decided to support Gabriel.[60]

Gabriel sent Imreffy to Rákóczi, offering to help Rákóczi seize two important domains in Upper Hungary if Rákóczi abdicated.[61] He informed Rudolph's commissioner, Zsigmond Forgách, on 13 February 1608 that Rákóczi had already agreed to leave Transylvania.[62] Although the Hajdús took control of the northwestern region of Partium, Gabriel forbade them to invade Transylvania proper.[63] János Petki announced Rákóczi's abdication at the Diet in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca in Romania) on 5 March of that year.[63]

Reign

Consolidation

The Diet elected Gabriel prince on 7 March 1608, and sent delegates to him in Nagyecsed.[64] Although his election was technically free, he controlled the strongest army in the principality (making resistance impossible).[64] He pledged to respect the laws of the principality, especially the privileges of the Three Nations, before accepting his election on 14 March.[65] Gabriel was ceremoniously installed in Kolozsvár on 31 March, and the Diet granted him the domains of Fogaras (now Făgăraș in Romania) and Kővár as hereditary estates.[66] He began settling the Hajdús in Partium, and granted Böszörmény to those forced to leave Nagykálló; others received parcels in Bihar County.[67] About 30,000 Hajdú soldiers received parcels of land from Gabriel during his reign.[68]

To assert his suzerainty over Wallachia and Moldavia, he decided to dethrone Prince Radu Șerban of Wallachia; however, the royal council and Michael Weiss (mayor of the important Transylvanian Saxon town of Brassó, now Brașov in Romania) dissuaded him.[69][70] Radu Șerban voluntarily swore fealty to Gabriel in the presence of his envoys on 31 May.[69] On 18 July, thirteen-year-old Prince of Moldavia Constantin I Movilă also acknowledged Gabriel's suzerainty and promised to pay a yearly tribute of 8,000 florins.[69] That month, Gabriel visited Brassó.[71] His feasts infuriated the burghers, who called him a drunkard or a greedy new Sardanapalus in defamatory poems.[72][73] Gabriel's promiscuity was notorious; he reportedly seduced young women and promoted noblemen who were willing to offer him their wives.[74]

He sent Bethlen to Istanbul and Imreffy to Kassa to secure his recognition by the Sublime Porte and the royal court.[75] After a brief negotiation, Imreffy and representatives of Rudolph's brother Matthias (who had persuaded Rudolph to abdicate in his favor) signed two treaties on 20 August.[76][75] The first treaty summarized the privileges of the Hajdús in Royal Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania.[75] The second recognized Gabriel as lawful ruler of Transylvania, but forbade him to secede from the Holy Crown of Hungary.[75] Bethlen returned from Istanbul in late November with the sultan's delegates, who brought the ahidnâme confirming Gabriel's election.[75] The sultan exempted Transylvania from paying the customary tribute for three years.[77]

Romanian Orthodox priests approached Gabriel for support against noblemen who treated them like serfs.[72] At their request, he freed them from taxation and service demands by the landowners in June 1609.[72] Gabriel also granted them the right to freely move about the principality.[72][76] At his initiative, in October the Diet abolished all grants which had exempted some noble estates from taxation.[76]

Assassination attempt

While Gabriel was sleeping at István Kendi's home in Szék (now Sic in Romania) during the night of 10–11 March 1610, a man entered his bedroom.[72][78] Although the intruder had wanted to stab Gabriel, he changed his mind and confessed that Kendi and other (mostly-Catholic) noblemen had hired him.[78][79] Kendi soon fled to Royal Hungary, but his accomplices were captured.[78] The Diet sentenced the conspirators to death on 24 March, and their estates were confiscated.[80] Gabriel made Imreffy chancellor and Bethlen captain of the Székelys.[81]

The motivation for the conspiracy is unclear.[79] According to the contemporary Tamás Borsos, the conspirators wanted to murder Gabriel because his undisciplined Hajdú troops had destroyed many villages.[79] Calvinist pastor Máté Szepsi Laczkó said that the Catholic noblemen wanted to get rid of the Protestant prince.[82] Others claimed that Boldizsár Kornis (captain of the Székelys) joined the plot because Gabriel had tried to seduce his young wife.[83]

Gabriel met Palatine of Hungary György Thurzó in Királydaróc (now Craidorolț in Romania) in June, but they could not reach an agreement.[84] He said during the negotiations that he was a sovereign, but the palatine was merely a "lord's serf".[85] After returning to Transylvania, Gabriel planned to reunite Royal Hungary and Transylvania under his rule with Ottoman support.[86] Although he ordered the princes of Moldavia and Wallachia to send reinforcements and the Saxons to pay a tax of 100,000 florins, the prince of Moldavia did not send troops and the Saxons paid only 10,000 florins.[86] Imreffy again went to Royal Hungary to negotiate with Thurzó in Kassa.[86] By 15 August, they reached a compromise which resolved most of the contentious issues.[87] However, Matthias II did not ratify the agreement because it stated that Transylvania was not required to provide military assistance to Royal Hungary against the Ottomans.[88]

Conflicts

Gabriel went to Szeben (now Sibiu in Romania), the wealthiest Saxon town, on 10 December.[89] Although only 50 soldiers accompanied him into the town, his army was stationed on the outskirts.[90] Gabriel stopped at the gate of the town the following day, pretending that he only wanted to study it; while the gate was open, his army unexpectedly marched in and captured the town without resistance.[89] He said that he wanted to secure his entry into Szeben because the Saxons could refuse monarchs entry into their towns.[91] According to the contemporaneous Diego de Estrada, Gabriel wanted to transfer his capital to Szeben from Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia in Romania), which had been destroyed during the Long Turkish War.[91] The Diet declared Szeben capital of the principality on 17 December, limiting its privileges, authorizing noblemen to acquire real estate and Calvinist priests to preach in the town's Lutheran churches.[92][93]

Gabriel launched a military campaign against Wallachia on 26 December.[81][94] Radu Şerban fled the country, enabling Gabriel to take possession of Târgoviște without resistance.[81][95] Gabriel styled himself prince of Wallachia in a 26 January 1611 charter.[96] According to Radu Popescu's chronicle, his troops brought pillage, destruction and death to the countryside.[97] Gabriel sent his envoys to Istanbul, asking Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I to confirm his rule in Wallachia.[96] He outlined a plan for the conquest of Poland.[81] He also demanded compensation for the salaries of his Hajdús from the Ottomans, who began to call him "Deli Kiral" (Mad King) because of his actions.[95]

The Ottoman governors of Buda and Temesvár (now Timișoara in Romania) invaded the Hajdú villages in Partium, forcing them to hurry back and defend their homes.[98][99] Ahmed I granted Wallachia to Radu Mihnea and ordered Gabriel to return to Transylvania in March.[100][101] Although the sultan's decision outraged Gabriel, he had no choice but to accept it.[101] Radu Şerban ousted Radu Mihnea from Wallachia at the head of an army of Cossack and Moldavian mercenaries.[101] The Diet ordered the mobilization of the Transylvanian army, authorizing Gabriel to collect an extraordinary tax in April.[102] However, Michael Weiss (who had regarded Gabriel as a new Nero) incited the burghers of Brassó to rise up against the monarch.[103] Gabriel dispatched Hajdú captain András Nagy to lay siege to Brassó, but Weiss bribed Nagy to lift the siege.[104] Radu Şerban invaded Burzenland (now Țara Bârsei in Romania) unexpectedly, and routed Gabriel's army near Brassó on 8 July 1611.[105] Gabriel barely escaped from the battlefield to Szeben.[106][107]

Matthias II considered Gabriel's attack against Wallachia as treachery, because he regarded Transylvania and the two Romanian principalities as realms of the Hungarian Crown.[108] Zsigmond Forgách, commander-in-chief of Upper Hungary, invaded Transylvania in late June.[109][99] Although Nagy and the Hajdús under his command supported Forgách, most Protestant noblemen refused to join the invasion.[110] Most Transylvanians regarded the invasion as an unlawful action, and only the Saxons were willing to support Forgách.[111] He and Radu Şerban besieged Szeben, but could not capture it.[112] Gabriel sent envoys to Istanbul, seeking assistance from the Sublime Porte.[113] Nagy and his Hajdú troops deserted Forgách and routed the reinforcements sent to him from Upper Hungary in mid-September.[114] After learning of the arrival of Ottoman troops to support Gabriel, Radu Şerban withdrew from Szeben; this forced Forgách to lift the siege.[115][99] The Transylvanian army routed the retreating royal troops, capturing hundreds of soldiers.[115]

Gabriel led his army from Szeben to Várad, but the Ottoman troops did not accompany him.[116] Delegates of the counties and towns of Upper Hungary persuaded Thurzó to begin negotiations with Gabriel, and their envoys signed an agreement in Tokaj in December.[117] Gabriel pledged to send delegates to the Diet of Hungary and not allow serfs to join the Hajdús.[118] However, the princes of the Holy Roman Empire persuaded Matthias II not to ratify the treaty until Gabriel reached an agreement with the Saxons.[119]

Meanwhile, Gabriel sent Hajdú captain András Géczi to Istanbul to express his gratitude for Ottoman support.[120][121] Géczi made an agreement with Michael Weiss in Brassó, however, and asked for Gabriel's removal on behalf of the Three Nations of Transylvania in Istanbul in November.[122][121] The Imperial Council of the Ottoman Empire accepted the proposal, and decided to replace Gabriel with Géczi.[121] After the burghers of Brassó refused to surrender, Gabriel invaded Burzenland and captured seven Saxon fortresses in late March and early April 1612.[123] The Diet of Transylvania urged the Saxons of Brassó to surrender in May, but the Three Nations delegates did not punish the noblemen who had fled to the town.[124] Gabriel proposed a month later at the Diet that the principality should renounce the sultan's suzerainty, but his proposal was refused.[121]

Géczi sent letters to András Nagy (who promised to murder Gabriel), but Nagy's letter was captured.[119] Gabriel killed Nagy or had him executed in August, according to various sources.[119] Gabriel Bethlen (the leading figure of the pro-Ottoman policy) fled to Ottoman territory on 12 September, and visited the Ottoman governors of Temesvár, Buda and Kanizsa.[125] With their help, he contacted the grand vizier Nasuh Pasha.[126] Weiss, who wanted to install Géczi as prince in Gyulafehérvár, left Brassó at the head of an undisciplined army on 8 October 1612.[127] Gabriel attacked Weiss and his troops, annihilating them six days later.[127][128] Weiss was beheaded on the battlefield, and Géczi withdrew to Brassó.[129] The Diet sentenced the absent Géczi and Bethlen to death, granting amnesty to those who had surrendered.[129]

Fall

The Diet authorized Gabriel to begin negotiations with Matthias II, and their envoys signed an alliance in Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia) on 24 December 1612.[130] Matthias sent his delegates to Transylvania to urge the Saxons to surrender to Gabriel.[130] The treaty outraged Ahmed I, who decided to replace Gabriel with Bethlen in March.[126][131] Matthias and Gabriel's envoys concluded a new treaty on 12 April, and Matthias acknowledged Gabriel's hereditary right to rule Transylvania.[132] In a secret agreement, Gabriel promised to support Matthias even against the Ottomans.[133] He granted a royal pardon to the Saxons and their allies, including Géczi (who was made commander of Gabriel's guard).[134]

Gabriel Bethlen left Istanbul in August, accompanied by Skender, the Pasha of Kanizsa.[126] Radu Mihnea invaded Transylvania from Wallachia in early September.[126] Canibek Giray, Khan of the Crimean Tatars, invaded the principality three weeks later.[126] By early October, Ottoman troops arrived to support Bethlen.[126] Gabriel fled from Transylvania proper and withdrew to Várad to seek assistance from Royal Hungary against Bethlen and his allies.[135] Zsigmond Forgách sent an army of 2,000 troops, commanded by Miklós Abafy, to Várad.[136]

Skender Pasha convoked the delegates of the Three Nations to a Diet at Gyulafehérvár.[126] The Diet dethroned Gabriel on 21 October, urging him in a letter of farewell to accept the decision,[137] and elected Bethlen prince two days later.[126] According to the contemporaneous historian Máté Szepsi Lackó, András Géczi and Miklós Abaffy soon hatched a plot to murder Gabriel in Várad.[138] They entered his room on 26 October 1613 and persuaded him to give them his sword, but did not attack the strong prince because he still had a dagger.[138] The following day, Abaffy told Gabriel that the troops from Royal Hungary wanted to see him.[139] After visiting Abaffy's army, Gabriel returned to Várad in a carriage.[139] Horsemen suddenly attacked the carriage, forcing it to turn into a narrow street.[139] Gabriel jumped out of the carriage, but was soon shot.[139] He tried to resist at a willow tree near the Pece Stream, but dozens of Hajdús attacked and killed him.[140] Hajdú infantry captain Balázs Nagy brought Gabriel's body first to Nagyecsed, and then to Nyírbátor.[141] His body lay unburied in the crypt of the church in Nyírbátor,[141] and he was ceremoniously buried at Bethlen's order only in 1628.[131]

Family

| Ancestors of Gabriel Báthory[4][142][143] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gabriel's wife, Anna, was the daughter of György Horváth Palocsai and Krisztina Sulyok.[144] According to Nagy Szabó, she was "a big fat woman" and Gabriel "did possibly not love her too much".[144] Michael Weiss said that Gabriel's separation from his wife was a reason for the Saxons' rebellion because it contradicted divine law.[145] Bethlen accused Gabriel of an incestuous affair with his sister, Anna, first mentioning the rumour in Istanbul in 1613 in an attempt to depose him.[146] The accusation was repeated during a secret lawsuit against Anna, whom Bethlen accused of witchcraft in 1614.[147]

References

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 11.

- ^ a b Szabó 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 12–14.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 13.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 14.

- ^ a b Keul 2009, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 261.

- ^ Dörner 2009, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Felezeu 2009, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Barta 1994, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Dörner 2009, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 265.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Keul 2009, p. 139.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 24.

- ^ a b Horn 2002, p. 187.

- ^ Horn 2002, p. 188.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 27.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 295.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Barta 1994, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Keul 2009, p. 142.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 26.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 26, 45–46.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 37, 42.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 37.

- ^ a b Barta 1994, p. 297.

- ^ Felezeu 2009, p. 37.

- ^ a b Keul 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 55, 289.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 60.

- ^ Keul 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 289.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 49, 289.

- ^ Keul 2009, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 70.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 60, 71–72.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 73.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 74.

- ^ Keul 2009, p. 159.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 75.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 81, 83, 94.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 83.

- ^ a b Péter 1994, p. 304.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 82.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 92.

- ^ Keul 2009, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 98.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 88.

- ^ Péter 1994, p. 305.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 89, 289.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 89.

- ^ a b Keul 2009, p. 160.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 101.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 90.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 103.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 104.

- ^ a b Barta 1994, p. 305.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 105.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 105, 121.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 126.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Barta 1994, p. 306.

- ^ Jakó 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e Keul 2009, p. 161.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 145.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e Barta 1994, p. 307.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 290.

- ^ Andea 2009, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Barta 1994, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d Barta 1994, p. 309.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 153.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 152.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 291.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 118.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 168.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 172.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 176.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 174.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 174, 177–178.

- ^ Keul 2009, p. 165.

- ^ Andea 2009, p. 116.

- ^ a b Felezeu 2009, p. 34.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 181.

- ^ Jakó 2009, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Barta 1994, p. 310.

- ^ Felezeu 2009, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 183.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 189, 215.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 194, 290–291.

- ^ Jakó 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 201.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 197.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 198.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 199.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 200.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 203.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 205.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 207.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 208.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 209.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 210.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Nagy 1988, p. 223.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d Barta 1994, p. 311.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 292.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 221.

- ^ Barta 1994, pp. 311–313.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barta 1994, p. 313.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 224.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 312.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 225.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 259.

- ^ a b Szabó 2012, p. 205.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 259, 261.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 261.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 226.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 274, 276.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 276.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 279.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 281.

- ^ a b c d Nagy 1988, p. 282.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 284.

- ^ Horn 2002, pp. 13–14, 244–245.

- ^ Markó 2000, pp. 232, 282, 289.

- ^ a b Nagy 1988, p. 66.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 217.

- ^ Nagy 1988, p. 61.

- ^ Nagy 1988, pp. 61–62.

Sources

- Andea, Susana (2009). "Political Evolution in the 17th Century-From Stephen Bocskai to Michael Apafi". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 113–131. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barta, Gábor (1994). "The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 247–300. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dörner, Anton (2009). "Power structures". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 133–178. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Felezeu, Călin (2009). "The International Political Background (1541–1699); The Legal Status of the Principality of Transylvania in Its Relations with the Ottoman Porte". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vo. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 15–73. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horn, Ildikó (2002). Báthory András [Andrew Báthory] (in Hungarian). Új Mandátum. ISBN 963-9336-51-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jakó, Klára (2009). "Báthory Gábor és a román vajdaságok [Gabriel Báthory and the Romanian Principalities]". In Papp, Klára; Jeney-Tóth, Annamária; Ulrich, Attila (eds.). Báthory Gábor és kora [Gabriel Báthory and His Times]. Debreceni Egyetem Történeti Intézete; Erdély-történeti Alapítvány. pp. 123–132. ISBN 978-963-473-272-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Markó, László (2000). A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon [Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia] (in Hungarian). Magyar Könyvklub. ISBN 963-547-085-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nagy, László (1988). Tündérkert fejedelme: Báthory Gábor [Prince of the Pixies' Garden: Gabriel Gáthory]. Zrínyi Kiadó. ISBN 963-326-947-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Péter, Katalin (1994). "The Golden Age of the Principality (1606–1660)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 301–358. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Szabó, Péter Károly (2012). "Báthory Gábor". In Gujdár, Noémi; Szatmáry, Nóra (eds.). Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története [Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania] (in Hungarian). Reader's Digest. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-963-289-214-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Heraldique Europeenne: Transylvania, including the coats-of-arms of Gabriel Báthory, Prince of Transylvania

- Marek, Miroslav. "A genealogy of the Somlyó branch of the Báthory family". Genealogy.EU.

- Péter, Katalin. "Gábor Báthory leads the Hajdús". mek.oszk.hu.