Piano Concerto No. 1 (Tchaikovsky)

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2018) |

| Piano Concerto in B♭ minor | |

|---|---|

| No. 1 | |

| by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky | |

The composer, c. 1875 | |

| Catalogue | Op. 23 |

| Composed | 1874–75 |

| Dedication | Hans von Bülow |

| Performed | 25 October 1875: Boston |

| Movements | three |

| Audio samples | |

I. Allegro (18:47) | |

II. Andantino (6:28) | |

III. Allegro (6:10) | |

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B♭ minor, Op. 23, was composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky between November 1874 and February 1875.[1] It was revised in the summer of 1879 and again in December 1888. The first version received heavy criticism from Nikolai Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky's desired pianist. Rubinstein later repudiated his previous accusations and became a fervent champion of the work. It is one of the most popular of Tchaikovsky's compositions and among the best known of all piano concertos.[2]

Instrumentation

The work is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B♭, two bassoons, four horns in F, two trumpets in F, three trombones (two tenor, one bass), timpani, solo piano, and strings.

Structure

The concerto follows the traditional form of three movements:

A standard performance lasts between 30 and 36 minutes, the majority of which is taken up by the first movement.

I. Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso – Allegro con spirito

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The first movement is initiated with four emphatic B♭ minor chords, which lead to a lyrical and passionate theme in D♭ major. This subsidiary theme is heard three times, the last of which is preceded by a piano cadenza,[3] and never appears again throughout the movement. The introduction ends in a subdued manner. The exposition proper then begins in the concerto's tonic minor key, with a Ukrainian folk theme based on a melody that Tchaikovsky heard performed by blind lirnyks at a market in Kamianka (near Kyiv). A short transitional passage is a call and response section on the tutti and the piano, alternating between high and low registers. The second subject group consists of two alternating themes, the first of which features some of the melodic contours from the introduction. This is answered by a smoother and more consoling second theme, played by the strings and set in the subtonic key (A♭ major) over a pedal point, before a more turbulent reappearance of the woodwind theme, this time re-enforced by driving piano arpeggios, gradually builds to a stormy climax in C minor that ends in a perfect cadence on the piano. After a short pause, a closing section, based on a variation of the consoling theme, closes the exposition in A♭ major.[4]

The development section transforms this theme into an ominously building sequence, punctuated with snatches of the first subject material. After a flurry of piano octaves, fragments of the "plaintive" theme are revisited for the first time in E♭ major, then for the second time in G minor, and then the piano and the strings take turns to play the theme for the third time in E major while the timpani furtively plays a tremolo on a low B until the first subject's fragments are continued.

The recapitulation features an abridged version of the first subject, working around to C minor for the transition section. In the second subject group, the consoling second theme is omitted, and instead the first theme repeats, with a reappearance of the stormy climactic build that was previously heard in the exposition, but this time in B♭ major. However, this time the excitement is cut short by a deceptive cadence. A brief closing section, made of G-flat major chords played by the whole orchestra and the piano, is heard. Then a piano cadenza appears, the second half of which contains subdued snatches of the second subject group's first theme in the work's original minor key. The B♭ major is restored in the coda, when the orchestra re-enters with the second subject group's second theme; the tension then gradually builds up, leading to a triumphant conclusion, ending with a plagal cadence.

Question of the introduction

The introduction's theme is notable for its apparent formal independence from the rest of the movement and from the concerto as a whole, especially given its setting not in the work's nominal key of B♭ minor but rather in D♭ major, that key's relative major. Despite its very substantial nature, this theme is only heard twice, and it never reappears at any later point in the concerto.[5]

Russian music historian Francis Maes writes that because of its independence from the rest of the work,

For a long time, the introduction posed an enigma to analysts and critics alike. ... The key to the link between the introduction and what follows is ... Tchaikovsky's gift of hiding motivic connections behind what appears to be a flash of melodic inspiration. The opening melody comprises the most important motivic core elements for the entire work, something that is not immediately obvious, owing to its lyric quality. However, a closer analysis shows that the themes of the three movements are subtly linked. Tchaikovsky presents his structural material in a spontaneous, lyrical manner, yet with a high degree of planning and calculation.[6]

Maes continues by mentioning that all the themes are tied together by a strong motivic link. These themes include the Ukrainian folk song "Oi, kriache, kriache, ta y chornenkyi voron ..." as the first theme of the first movement proper, the French chansonette, "Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire." (Translated as: One must have fun, dance and laugh) in the middle section of the second movement and a Ukrainian vesnianka "Vyidy, vyidy, Ivanku" or greeting to spring which appears as the first theme of the finale; the second theme of the finale is motivically derived from the Russian folk song "Podoydi, podoydi vo Tsar-Gorod" and also shares this motivic bond. The relationship between them has often been ascribed to chance because they were all well-known songs at the time Tchaikovsky composed the concerto. It seems likely, though, that he used these songs precisely because of their motivic connection and used them where he felt necessary. "Selecting folkloristic material," Maes writes, "went hand in hand with planning the large-scale structure of the work."[7]

All this is in line with the earlier analysis of the Concerto published by Tchaikovsky authority David Brown, who further suggests that Alexander Borodin's First Symphony may have given the composer both the idea to write such an introduction and to link the work motivically as he does. Brown also identifies a four-note musical phrase ciphered from Tchaikovsky's own name and a three-note phrase likewise taken from the name of soprano Désirée Artôt, to whom the composer had been engaged some years before.[8]

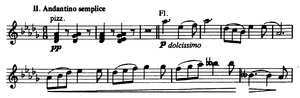

II. Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo I

The second movement, in D♭ major, is written in 6

8 time. The tempo marking of "andantino semplice" lends itself to a range of interpretations; the World War II-era recording of Vladimir Horowitz (as soloist) and Arturo Toscanini (as conductor) completed the movement in under six minutes,[9] while towards the other extreme, Lang Lang recorded the movement, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim, in eight minutes.[10]

- Measures 1–58: Andantino semplice

- Measures 59–145: Prestissimo

- Measures 146–170: Tempo I

After a brief pizzicato introduction, the flute carries the first statement of the theme. The flute's opening four notes are A♭–E♭–F–A♭, while each other statement of this motif in the remainder of the movement substitutes the F for a (higher) B♭. The British pianist Stephen Hough suggests this may be an error in the published score, and that the flute should play a B♭.[11] After the flute's opening statement of the melody, the piano continues and modulates to F major. After a bridge section, two cellos return with the theme in D♭ major and the oboe continues it. The "A" section ends with the piano holding a high F major chord, pianissimo. The movement's "B" section is in D minor (the relative minor of F major) and marked "allegro vivace assai" or "prestissimo", depending on the edition. It commences with a virtuosic piano introduction before the piano assumes an accompanying role and the strings commence a new melody in D major. The "B" section ends with another virtuosic solo passage for the piano, leading into the return of the "A" section. In the return, the piano makes the first, now ornamented, statement of the theme. The oboe continues the theme, this time resolving it to the tonic (D♭ major) and setting up a brief coda which finishes ppp on another plagal cadence.

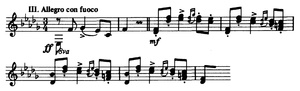

III. Allegro con fuoco – Molto meno mosso – Allegro vivo

The final movement, in Rondo form, starts with a very brief introduction. The A theme, in B♭ minor, is march-like and upbeat. This melody is played by the piano until the orchestra plays a variation of it ff. The B theme, in D♭ major, is more lyrical and the melody is first played by the violins, and by the piano second. A set of descending scales leads to the abridged version of the A theme.

The C theme is heard afterwards, modulating through various keys, containing dotted rhythm, and a piano solo leads to:

The later measures of the A section are heard, and then the B appears, this time in E♭ major. Another set of descending scales leads to the A once more. However, this time, it ends with a half cadence on a secondary dominant, in which the coda starts. An urgent build-up leads to a sudden crash, and it fuses into a dramatic and extended climatic episode, starting mysteriously and gradually building up to a triumphant dominant prolongation. Then the melodies from the B theme is heard triumphantly in B♭ major. After that, the final part of the coda, marked allegro vivo, draws the work to a heroic conclusion on a perfect authentic cadence.

History

Tchaikovsky revised the concerto three times, the last being in 1888, which is the version usually now played. One of the most prominent differences between the original and final versions is that in the opening section, the octave chords played by the pianist, over which the orchestra plays the famous theme, were originally written as arpeggios. The work was also arranged for two pianos by Tchaikovsky, in December 1874; this edition was revised December 1888.[citation needed]

Disagreement with Rubinstein

There is some confusion regarding to whom the concerto was originally dedicated. It was long thought that Tchaikovsky initially dedicated the work to Nikolai Rubinstein, and Michael Steinberg writes that Rubinstein's name is crossed off the autograph score.[12] However, Brown writes that there is actually no truth in the assertion that the work was written to be dedicated to Rubinstein.[13] Tchaikovsky did hope that Rubinstein would perform the work at one of the 1875 concerts of the Russian Musical Society in Moscow. For this reason he showed the work to him and another musical friend, Nikolai Hubert, at the Moscow Conservatory on December 24, 1874/January 5, 1875, just three days after finishing its composition.[14] Brown writes, "This occasion has become one of the most notorious incidents in the composer's biography."[15] Three years later Tchaikovsky shared what happened with his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck:

I played the first movement. Not a single word, not a single remark! If you knew how stupid and intolerable is the situation of a man who cooks and sets before a friend a meal, which he proceeds to eat in silence! Oh, for one word, for friendly attack, but for God's sake one word of sympathy, even if not of praise. Rubinstein was amassing his storm, and Hubert was waiting to see what would happen, and that there would be a reason for joining one side or the other. Above all I did not want sentence on the artistic aspect. My need was for remarks about the virtuoso piano technique. R's eloquent silence was of the greatest significance. He seemed to be saying: "My friend, how can I speak of detail when the whole thing is antipathetic?" I fortified myself with patience and played through to the end. Still silence. I stood up and asked, "Well?" Then a torrent poured from Nikolay Grigoryevich's mouth, gentle at first, then more and more growing into the sound of a Jupiter Tonans. It turned out that my concerto was worthless and unplayable; passages were so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written that they were beyond rescue; the work itself was bad, vulgar; in places I had stolen from other composers; only two or three pages were worth preserving; the rest must be thrown away or completely rewritten. "Here, for instance, this—now what's all that?" (he caricatured my music on the piano) "And this? How can anyone ..." etc., etc. The chief thing I can't reproduce is the tone in which all this was uttered. In a word, a disinterested person in the room might have thought I was a maniac, a talented, senseless hack who had come to submit his rubbish to an eminent musician. Having noted my obstinate silence, Hubert was astonished and shocked that such a ticking off was being given to a man who had already written a great deal and given a course in free composition at the Conservatory, that such a contemptuous judgment without appeal was pronounced over him, such a judgment as you would not pronounce over a pupil with the slightest talent who had neglected some of his tasks—then he began to explain N.G.'s judgment, not disputing it in the least but just softening that which His Excellency had expressed with too little ceremony.

I was not only astounded but outraged by the whole scene. I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition, and I no longer need lessons from anyone, especially when they are delivered so harshly and unfriendlily. I need and shall always need friendly criticism, but there was nothing resembling friendly criticism. It was indiscriminate, determined censure, delivered in such a way as to wound me to the quick. I left the room without a word and went upstairs. In my agitation and rage I could not say a thing. Presently R. enjoined me, and seeing how upset I was he asked me into one of the distant rooms. There he repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places where it would have to be completely revised, and said that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing my thing at his concert. "I shall not alter a single note," I answered, "I shall publish the work exactly as it is!" This I did.[16]

Tchaikovsky biographer John Warrack mentions that, even if Tchaikovsky were restating the facts in his favor,

it was, at the very least, tactless of Rubinstein not to see how much he would upset the notoriously touchy Tchaikovsky. ... It has, moreover, been a long-enduring habit for Russians, concerned about the role of their creative work, to introduce the concept of 'correctness' as a major aesthetic consideration, hence to submit to direction and criticism in a way unfamiliar in the West, from Balakirev and Stasov organizing Tchaikovsky's works according to plans of their own, to, in our own day, official intervention and the willingness of even major composers to pay attention to it.[17]

Warrack adds that Rubinstein's criticisms fell into three categories. First, he thought the writing of the solo part was bad, "and certainly there are passages which even the greatest virtuoso is glad to survive unscathed, and others in which elaborate difficulties are almost inaudible beneath the orchestra."[18] Second, he mentioned "outside influences and unevenness of invention ... but it must be conceded that the music is uneven and that [it] would, like all works, seem the more uneven on a first hearing before its style had been properly understood."[19] Third, the work probably sounded awkward to a conservative musician such as Rubinstein.[19] While the introduction in the "wrong" key of D♭ (for a composition supposed to be written in B♭ minor) may have taken Rubinstein aback, Warrack explains, he may have been "precipitate in condemning the work on this account or for the formal structure of all that follows."[19]

Hans von Bülow

Brown writes that it is not known why Tchaikovsky next approached German pianist Hans von Bülow to premiere the work,[13] although the composer had heard Bülow play in Moscow earlier in 1874 and had been taken with the pianist's combination of intellect and passion, and the pianist was likewise an admirer of Tchaikovsky's music.[20] Bülow was preparing to go on a tour of the United States. This meant that the concerto would be premiered half a world away from Moscow. Brown suggests that Rubinstein's comments may have deeply shaken him about the concerto, though he did not change the work and finished orchestrating it the following month, and that his confidence in the piece may have been so shaken that he wanted the public to hear it in a place where he would not have to personally endure any humiliation if it did not fare well.[13] Tchaikovsky dedicated the work to Bülow, who described it as "so original and noble".

The first performance of the original version took place on October 25, 1875, in Boston, conducted by Benjamin Johnson Lang and with Bülow as soloist. Bülow had initially engaged a different conductor, but they quarrelled, and Lang was brought in on short notice.[21] According to Alan Walker, the concerto was so popular that Bülow was obliged to repeat the Finale, a fact that Tchaikovsky found astonishing.[22] Although the premiere was a success with the audience, the critics were not so impressed. One wrote that the concerto was "hardly destined ..to become classical".[23] George Whitefield Chadwick, who was in the audience, recalled in a memoir years later: "They had not rehearsed much and the trombones got in wrong in the 'tutti' in the middle of the first movement, whereupon Bülow sang out in a perfectly audible voice, The brass may go to hell".[24] However, the work fared much better at its performance in New York City on November 22, under Leopold Damrosch.[25]

Benjamin Johnson Lang appeared as soloist in a complete performance of the concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on February 20, 1885, under Wilhelm Gericke.[21] Lang previously performed the first movement with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in March 1883, conducted by Georg Henschel, in a concert in Fitchburg, Massachusetts.

The Russian premiere took place on November 1/13, 1875[26] in Saint Petersburg, with the Russian pianist Gustav Kross and the Czech conductor Eduard Nápravník. In Tchaikovsky's estimation, Kross reduced the work to "an atrocious cacophony".[27] The Moscow premiere took place on November 21/December 3, 1875, with Sergei Taneyev as soloist. The conductor was none other than Nikolai Rubinstein, the same man who had comprehensively criticised the work less than a year earlier.[20] Rubinstein had come to see its merits, and he played the solo part many times throughout Europe. He even insisted that Tchaikovsky entrust the premiere of his Second Piano Concerto to him, and the composer would have done so had Rubinstein not died.[citation needed] At that time, Tchaikovsky considered rededicating the work to Taneyev, who had performed it splendidly, but ultimately the dedication went to Bülow.

Tchaikovsky published the work in its original form,[28] but in 1876 he happily accepted advice on improving the piano writing from German pianist Edward Dannreuther, who had given the London premiere of the work,[29] and from Russian pianist Alexander Siloti several years later. The solid chords played by the soloist at the opening of the concerto may in fact have been Siloti's idea, as they appear in the first (1875) edition as rolled chords, somewhat extended by the addition of one or sometimes two notes which made them more inconvenient to play but without significantly altering the sound of the passage. Various other slight simplifications were also incorporated into the published 1879 version. Further small revisions were undertaken for a new edition published in 1890.

The American pianist Malcolm Frager unearthed and performed the original version of the concerto.[30][when?]

In 2015, Kirill Gerstein made the world premiere recording of the 1879 version. It received an ECHO Klassik award in the Concerto Recording of the Year category. Based on Tchaikovsky's own conducting score from his last public concert, the new critical Urtext edition was published in 2015 by the Tchaikovsky Museum in Klin, tying in with Tchaikovsky's 175th anniversary and marking 140 years since the concerto's world premiere in Boston in 1875. For the recording, Kirill Gerstein was granted special pre-publication access to the new Urtext edition.[31]

Notable performances

- Theodore Thomas programmed the concerto for the first concerts of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, given on October 16 and 17, 1891. Rafael Joseffy was the soloist.[32]

- Wassily Sapellnikoff, who played the concerto many times with Tchaikovsky himself conducting, made a record in 1926 with Aeolian Orchestra under Stanley Chapple.[33]

- Arthur Rubinstein recorded the concerto five times: with John Barbirolli in 1932; with Dmitri Mitropoulos in 1946; with Artur Rodzinski live in 1946; with Carlo Maria Giulini in 1961; and with Erich Leinsdorf in 1963.

- Solomon recorded the concerto thrice, most notably with Philharmonia Orchestra under Issay Dobrowen in 1949.

- Egon Petri in 1937 with London Philharmonic Orchestra under Walter Goehr.

- Vladimir Horowitz performed this piece as part of a World War II fundraising concert in 1943, with his father-in-law, the conductor Arturo Toscanini, conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Two performances of Horowitz playing the concerto and Toscanini conducting were eventually released on records and CDs – the live 1943 rendition, and an earlier studio recording made in 1941.

- Sviatoslav Richter in 1962 with Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Richter also made recordings in 1954, 1957, 1958 and 1968.

- Emil Gilels recorded the concerto more than a dozen times, both live and in studio. The studio recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1955 is most well regarded.

- Lazar Berman recorded the concerto in studio with Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan in 1975 playing the revised version, and live in 1986 with Yuri Temirkanov playing the original version of 1875.[34]

- Van Cliburn won the First International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958 with this piece, surprising some people, as he was an American competing in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. His subsequent RCA LP recording with Kirill Kondrashin was the first classical LP to go platinum.

- Claudio Arrau recorded the concerto twice, once in 1960 with Alceo Galliera and the Philharmonia Orchestra and again in 1979 with Sir Colin Davis and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

- Martha Argerich recorded the concerto in 1971 with Charles Dutoit and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. She also recorded it in 1980 with Kirill Kondrashin and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, as well as in 1994 with Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic.

- Horacio Gutiérrez's performance of this piece at the Tchaikovsky piano competition (1970) resulted in a silver medal. He later recorded with the Baltimore Symphony and David Zinman.

- Vladimir Ashkenazy recorded the concerto in 1963 with Lorin Maazel and the London Symphony Orchestra.

- Evgeny Kissin performed and recorded the concerto live with Herbert von Karajan during New Year's Eve Concert in 1988, being one of the last recordings of the maestro.

- Stanislav Ioudenitch won the gold medal at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001 performing this concerto with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra and James Conlon in the final round. His live recording of this concerto from the final round is available on the DVD The Cliburn: Playing on the Edge.

In popular culture

- The introduction to the first movement was played during the closing ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia. It was used during the final leg of the Olympic torch relay during the Opening Ceremonies of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, Soviet Union.

- This piece was also further popularized among many Americans when it was used as the theme to Orson Welles's famous radio series, The Mercury Theatre on the Air. The Concerto came to be associated with Welles throughout his career and was often played when introducing him as a guest on both radio and television. The main theme was also made into a popular song titled Tonight We Love by bandleader Freddy Martin in 1941.[35]

- The opening bars of the concerto were played in a Monty Python's Flying Circus sketch in which a pianist (who is said to be Sviatoslav Richter) struggles, like Harry Houdini, to escape from a locked bag and other restraints, but is nevertheless able to pound away at the keyboard. It was also played by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra while it went to the bathroom.

- The concerto is used for the opening credits of 1941's The Great Lie, and is played by Mary Astor's character Sandra Kovak at the end of the movie.

- The concerto was played by classical pianist and comedian Oscar Levant backed with a full symphony orchestra in the 1949 MGM musical film The Barkleys of Broadway.

- Liberace's version of the concerto is played in the 1990 film Misery.

- The title cut from Pink Martini's 2009 album Splendor in the Grass employs the famous theme from the first movement.

- The concerto is used in the 1971 cult film classic Harold and Maude in the scene in which Harold's mother, played by Vivian Pickles, takes a swim in the pool while Harold, played by Bud Cort, fakes another suicide in the deep end as she calmly swims past.

- A disco rendition of the concerto is used to open the finale of The David Letterman Show as well as the debut episode of Late Night with David Letterman[36]

- The Concerto was used in The Meaning of Life.

- A segment of the concerto is used to open the title track of the 1981 Hooked on Classics project.

- The arcade video game City Connection used different variations of the introduction as musical background.

- The 1943 Merrie Melodies cartoon A Corny Concerto uses the introduction music for the opening credits.

- Segments of the television series Garfield and Friends, most notably the 30-second "Garfield Quickies," used the opening bars of the concerto, sometimes interspersed with "The Itsy Bitsy Spider."

References

- ^ Maes, 75.

- ^ Steinberg, 480.

- ^ Borg-Wheeler 2016.

- ^ Frivola-Walker 2010.

- ^ Steinberg, 477–478.

- ^ See J. Norris, The Russian Piano Concerto, 1:114–151. As cited in Maes, 76.

- ^ Maes, 76.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 22–24.

- ^ "Brahms / Tchaikovsky: Piano Concertos (Horowitz) (1940–1941)". Naxos Records. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Lang Lang / Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky". Deutsche Grammophon. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Hough, Stephen (27 June 2013). "STOP PRESS: a different mistake but a more convincing solution in Tchaikovsky's concerto". The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Steinberg, 477.

- ^ a b c Brown, Crisis Years, 18.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 16—17.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 17.

- ^ As quoted in Warrack, 78–79.

- ^ Warrack, 79.

- ^ Warrack, 79–80.

- ^ a b c Warrack, 80.

- ^ a b Steinberg, 476.

- ^ a b Margaret Ruthven Lang & Family Archived 2005-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alan Walker (2009). Hans von Bülow: A life and times. Oxford University Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780195368680.

- ^ Naxos[permanent dead link]

- ^ Steven Ledbetter, notes for Colorado Symphony Orchestra Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alan Walker (2009), p. 219

- ^ Tchaikovsky Research

- ^ Alexander Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, p. 166

- ^ Steinberg, 475.

- ^ Steinberg, 475—476.

- ^ All Music; Rogert Dettmer biography of Malcolm Frager. Retrieved 29 May 2014

- ^ BBC Music Magazine – Artist Interview: Kirill Gerstein, February 2015

- ^ http://csoarchives.wordpress.com/2016/10/15/125-moments-125-first-concert/

- ^ http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Piano_Concerto_No._1:_Recordings

- ^ http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Piano_Concerto_No._1:_Recordings#First_version_.281874-75.29

- ^ Gilliland, John (1994). Pop Chronicles the 40s: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40s (audiobook). ISBN 978-1-55935-147-8. OCLC 31611854. Tape 2, side B.

- ^ "David Letterman: The man who changed TV forever". bbc.com. 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

Sources

- Borg-Wheeler, Phillip (2016). Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No 1 & Nutcracker Suite – Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) (CD). Hyperion Records. SIGCD441.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Friskin, James, "The Text of Tchaikovsky's B-flat-minor Concerto," Music & Letters 50(2):246–251 (1969).

- Frivola-Walker, Marina (2010). Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840–1893): Piano Concerto No 1 in B-flat minor, Op 23 (CD). Hyperion Records. W10153.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Norris, Jeremy, The Russian Piano Concerto (Bloomington, 1994), Vol. 1: The Nineteenth Century. ISBN 0-253-34112-4.

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Serotsky, Paul (2000). Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23 (CD). Round Top Records. RTR006.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Steinberg, M. The Concerto: A Listener's Guide, Oxford (1998). ISBN 0-19-510330-0.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). ISBN 0-684-13558-2.

External links

Media related to Piano Concerto No. 1 (Tchaikovsky) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Piano Concerto No. 1 (Tchaikovsky) at Wikimedia Commons- Piano Concerto No. 1: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Tchaikovsky Research