Maratha Army

| Maratha Army | |

|---|---|

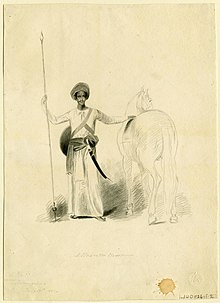

A painting depicting a Mahratta Light Horseman | |

| Active | circa 1650-1818 |

| Country | India |

| Allegiance | Maratha Empire |

| Type | Land-based Army |

| Size | Peak Size - Around 200,000 men |

| Commanders | |

| Senapati | Commander in chief |

Maratha (or Mahratta) Army refers to the land-based armed forces of the Maratha Empire, which existed from the late 17th to the early 19th centuries in India. The formation, rise, and decline of the armies of the Maratha Empire can be broadly divided into two eras

17th century

Chhatrapati Shivaji, the founder of Maratha empire, raised a small yet effective land army. For better administration, Shivaji abolished the land-grants or jagirs for military officers and made a cash payment. During the 17th century the Maratha Army was small in terms of numbers when compared to the Mughals, numbering some 100,000. Shivaji gave more emphasis to infantry as against cavalry, considering the rugged mountainous terrain he operated in. Further, Shivaji did not have access to the North Indian horse trading market, dominated by the Mughals. During this era, the armies of the Marathas were known for their agility due to the light equipment of both infantry and cavalry. Probably due to the rugged terrain, artillery was not given much emphasis. Artillery was mostly confined to the Maratha fortresses, which were located on hilltops, since it gave a strategic advantage and further these fortresses had abilities to withstand sieges (such as being equipped with sufficient water supply). The Marathas used weapons like muskets, matchlocks, firangi swords, clubs, bows, spears, daggers, etc.[1]

The Maratha Army, during Shivaji's era was systematic and disciplined. It probably possessed infantry and artillery capability equivalent to the European standards. A case in point here is that the Marathas achieved success in systematic elimination of all forts which came their way during the Battle of Surat circa 1664. Regards the artillery, Shivaji hired foreign (mainly Portuguese) mercenaries for assistance to manufacture weapons. The hiring of foreign mercenaries was not new to the Maratha military culture. Shivaji hired seasoned cannon-casting Portuguese technicians from Goa. The Marathas attached importance to hiring of experts, which can be corroborated by the fact that important posts in the army were offered to the officers in charge of the manufacture of guns.[2]

The Army deployed musketeers as well - both regular and mercenaries. During the late 17th century, there is a mention of the Marathas using well-armed musketeers during their attack on Goa (during the reign of Sambhaji). Further, during the same period there is also a mention of Marathas using Karnataki musketeers renowned for marksmanship[3][4]

Structure and Rank

Below was the structure and ranks of armies of the great Maratha at a high level during the reign of Chhatrapati Shivaji: Cavalry was divided into two at a high level:

- Shiledar: A shiledar brought his own horse and equipment. Although organized different, even shiledar converged into the Sarnobat (chief of Army)

- Bargir: One of the lowest rank (rank and file) cavalryman of the Marathas who was provided with horse and equipment from the State's stock[5]

The infantry consisted of the below:[6]

- Hetkari musketeers: Konkani musketeers recruited typically from the Konkan region, who possessed matchlocks and noted for their marksmanship

- Mavales: Foot soldier recruited typically from western Maharashtra

Ranks and salary of the cavalry are as below. The infantry had a similar structure[7]

- Sarnobat (chief of Army)(a part of the Council of Eight): 4000 to 5000 hons per year

- Panch Hazari: 2000 hons per year

- Hazari: 1000 hons per year

- Jumledar: 500 hons per year

- Havaldar: 125 hons per year

- Bargir: 9 hons per year

Infantry ranks (starting with senior-most rank):[8]

- Sarnobat (chief of Army)

- Saat (Seven) Hazari

- Hazari

- Jamdar

- Havaldar

- Nayak (or Naik)

- Paek

During the War of 27 Years

During the War of 27 Years (1680 to 1707) the Maratha State forces (regular army) dispersed and the theater of warfare became entire Southern India (or Deccan India). During this period the armies of the Mahratta resorted to guerrilla warfare; bands of irregular soldiers also joined in and it became a People's War. Raiding enemy's rear, isolated posts, supply lines was a feature during this period. Common men and women from virtually every town and village offered shelter to the Mahratta forces led by two valiant Generals - Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav[9][10]

Jadunath Sarkar the noted historian writes in his famous book namely military history of India about Santaji Ghorpade, a brilliant strategist who defeated Mughals in the 27 year war:

"He was a perfect master of this art, which can be more correctly described as Parthian warfare than as guerrilla tactics, because he could not only make night marches and surprises, but also cover long distances quickly and combine the movements of large bodied over wide areas with an accuracy and punctuality which were incredible in any Asiatic army other than those of Chengiz Khan and Tamurlane".

18th century

Pre-1761

During the 18th century the Maratha army continued its emphasis on its light cavalry, which proved better against the heavy cavalry of the Mughals. Post 1720, the armies of the Maratha Kingdom started making their presence felt in Northern India (the bastion of the Mughals) and scored numerous military victories, primarily due to the skills of Peshwa Bajirao I as a great cavalry leader and military strategist.[11] Bajirao Peshwa made excellent use of small and heavy ammunition (using it in excellent coordination) and used smothering tactics. The Marathas under Bajirao I would use their artillery to create a blanket of projectiles to smother the enemy.[12]

A hallmark of Baji Rao I's troops was that of long-distance cavalry attacks, typically light and agile cavalry. During his reign, the cavalry strength was some 100,000. Peshwa's own cavalry was called as Huzurat Cavalry which was an elite cavalry division.[13] Further, Baji Rao employed infantry consisting of flintlock-armed regulars[14]

Modernization pre-1761

When the Marathas confronted the French (allies of the Nizam) on battlefield in 1750s, they realized the importance of western-style disciplined infantry. Hence the process of modernization began even before the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). Sadashivrao Bhau Peshwa admired Western-style disciplined infantry.[15] Circa 1750s, the Marathas endeavored to hire the services of the French General Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau (who served in the Nizam’s Army) for training purposes, but when they failed in their efforts, they managed to hire Ibrahim Khan Gardi. Ibrahim Khan was an artillery expert trained under the leadership of Bussy. The word gardi is a corruption of the French word garde (guard) and this gardi formed the backbone of Maratha infantry.[16] Ibrahim Khan played a major role in re-configuring the Maratha artillery. He served the Marathas in the infamous Third Battle of Panipat. During the battle, out of the approximate 40,000 Maratha Army men, some 8000 or 9000 were artillery (Gardi Infantry). They possessed 200 cannons (consisting of heavy field-pieces as well as light camel or elephant-mounted zambaruks (a swivel gun equivalent) and also possessed handguns.[17]

During this era, sources state that the Marathas made use of both flintlocks and matchlocks and that their matchlocks had a technological advantage having superior range and velocity.[18] However at Third Battle of Panipat, they possessed mainly just swords and spears whilst Abdali possessed a larger force with flintlock muskets.[19]

Modernization post-1761

From the 17th century till the mid-18th century the artillery of the Marathas was more dependent on foreign gunners rather than their own. In a bid to Westernize the artillery, circa 1777, there is a mention of a Portuguese officer named Naronha heading the Peshwa’s artillery and further he had a number of European artillery men working under him.[20]

Post 1761 Mahadaji Shinde, a distinguished Maratha Maharaja, focused his attention on European artillery and secured the services of the noted Frenchman Benoît de Boigne. Benoît de Boigne had received training from the best of the European military schools. Following suit, the other Maratha chiefs (including their First Minister the Peshwa) such as the Holkars, the Bhosales, also raised French-trained artillery battalions. Further circa 1784, Mahadaji Shinde established a military-industrial complex for the armies of the Maratha near Agra. The ordnance factories of the Marathas made use of sophisticated indigenous technologies with more of adaptation as against innovation. Mahadaji Shinde created one of finest armies in India, with the help of the French and Portuguese and it also included a brigade known as Deccan Invincibles, which numbered some 27,000.[21]

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, with French-trained artillery and infantry, the Marathas managed to regain their lost ground in North India, however they could not match the superior artillery of the British East India Company, which in due course of time, among other reasons, led to the defeat of the Marathas at the Third Anglo-Maratha War and decline of their Empire itself.[22]

Employment of the Pindaris

Pindaris were irregular horsemen and their primary role was to plunder in return of pay. Pindaris composed of both Muslims and Marathas. They had implicit support from Maratha chiefs (Maharajas) such as Scindias of Gwalior, Holkars of Indore, and Bhosales of Nagpur. This band of freebooters accompanied Maratha forces during their campaigns and helped win wars in return for plunder and pay. They were a part of the Maratha Army during the Third Battle of Panipat and almost all Anglo-Maratha Wars.[23]

See also

References

- ^ Barua, Pradeep. The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1.

- ^ Cooper, Randolf. The Anglo-Maratha campaigns and the contest for India: the struggle for control of the south asian military economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-521-82444-3.

- ^ Alden, Dauril. The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond 1540-1750. Stanford University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-804-72271-4.

- ^ Richards, John. The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-521-25119- 2.

- ^ Chhabra, G.S. Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-1: 1707-1803). Lotus Press. p. 65. ISBN 81-89093-06-1.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik. War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58767-9.

- ^ Grewal, J. S. The State and Society in Medieval India. Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 0195667204.

- ^ Chhabra, G.S. Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-1: 1707-1803). Lotus Press. p. 65. ISBN 81-89093-06-1.

- ^ "Aurangzeb". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Kantak, M. R. The First Anglo-Maratha War, 1774-1783: A Military Study of Major Battles. Popular Prakashan. p. 11. ISBN 81-7154-696-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Roy, Tirthankar. An Economic History of early modern India. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-69063-8.

- ^ Cooper, Randolf. The Anglo-Maratha campaigns and the contest for India: the struggle for control of the south asian military economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-521-82444-3.

- ^ Alexander, J. P. Decisive Battles, Strategic Leaders. Partridge. p. 111.

- ^ Cooper, Randolf G S. The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0 521 82444 3.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black. p. 83. ISBN 81-7824-109-9.

- ^ Lafont, Jean Marie. Indika: essays in Indo-French relations, 1630-1976. University of Michigan. p. 428. ISBN 8173042780.

- ^ Barua, Pradeep. The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1.

- ^ Mount, Ferdinand. The Tears of the Rajas: Mutiny, Money and Marriage in India 1805-1905. Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-4711-2947-6.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik. War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-415-58767-9.

- ^ Butalia, Romesh. The evolution of artillery in India: from the battle of Plassey to the revolt of 1857. Allied publishers limited. p. 70. ISBN 81-7023-872-2.

- ^ Till, Geoffrey. Globalization and Defence in the Asia-Pacific: Arms Across Asia. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 0-203-89053-1.

- ^ Butalia, Romesh. The evolution of artillery in India: from the battle of Plassey to the revolt of 1857. Allied publishers limited. p. 70. ISBN 81-7023-872-2.

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pindaris